EQUITY IS FOR EVERYONE

July 17, 2023

It's hard to imagine a perfect world. But a better one? We can do that. “Equity for Everyone” is a mission committed to bringing every Utahn along in the process of imagining better health care, education, and opportunity for all. That includes the women seeking new lives and shelter through urban farming, the New American patient navigating an unfamiliar health care system, the rural doctor bringing care to a remote frontier town, veterans, new mothers, and survivors of opioid use disorder.

It’s the goal of our health care system to ensure everyone—no matter their age, ability, and identity—feels that they belong.

That’s why we’re weaving Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion (EDI) into the fabric of everything we do and inviting all to join us. We’re expanding education, improving hiring practices, and creating new standards of care to address health disparities as part of our commitment to a more inclusive world.

And we're not doing it alone. Meet the leaders building a better U—from the inside, out. They’re asking: What barriers prevent people from feeling like they belong? And how are we doing our part so that all feel included? Together, we're fostering belonging not just on our campus but throughout our community.

JOSÉ E. RODRÍGUEZ | (he/him), MD, FAAFP

Associate Vice President for Health Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at University of Utah Health

Passionate about community health outcomes, student and faculty success, and equity in medicine

José stands in front of Redwood Health Center, one of the U’s 11 community clinics that serves patients from Hispanic/Latinx, historically underrepresented, and refugee/New American backgrounds. When not engaged in academic research, José practices family medicine at this location.

PALOMA F. CARIELLO, MD, MPH | (she/her)

Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases and Associate Dean for Health Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

Passionate about medical education, women in leadership, and addressing language barriers

Paloma sits on the 3rd floor of the Gardner Commons building at the University of Utah, where two exhibits feature national flags and a layered map of the world. She is photographed in front of the South American portion of the map, home to her native Brazil.

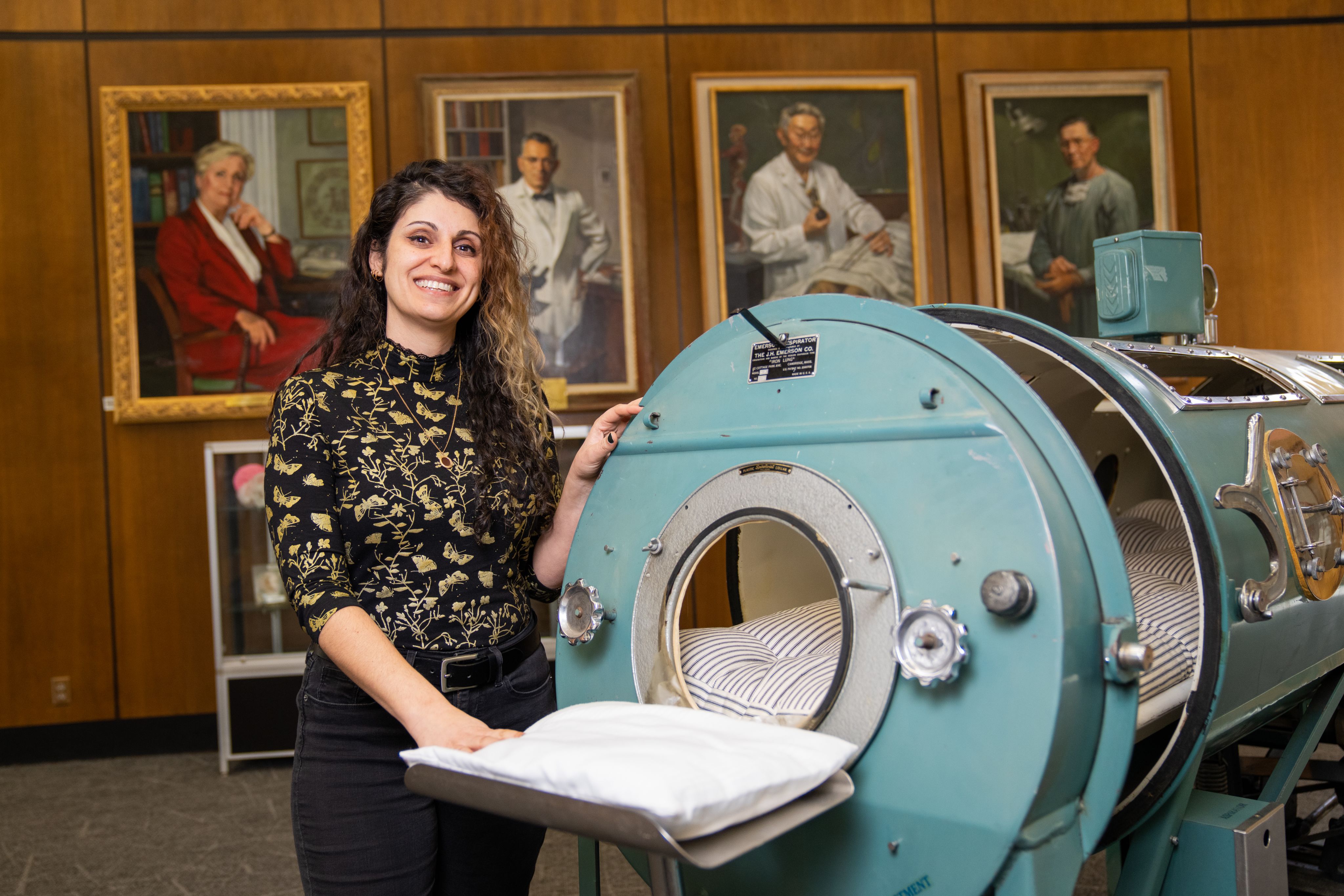

DONNA BALUCHI, MLIS | (she/they)

Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion Librarian at the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library

Passionate about cultural awareness, student resources, and broadening access to information

Donna stands at the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library in front of the last iron lung machine at the U. Behind her hangs a series of portraits displaying prominent physicians and researchers.

VALERIE FLATTES, PhD, APRN, MS, ANP-BC | (she/her)

Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at the University of Utah College of Nursing

Passionate about student belonging, sustainable action, and addressing barriers to education

Valerie sits in a study space on the upper floor of the College of Nursing building. During our shoot, Valerie played one of her favorite music genres to help her stay relaxed: a K-Pop (Korean Pop) playlist she listens to with her daughter while getting ready in the morning.

BART T. WATTS, DDS | (he/him)

Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Health Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at the University of Utah School of Dentistry

Passionate about community outreach, access to health care, and navigating allyship

Bart leans against a row of seats in a classroom at the School of Dentistry building. He teaches ethics alongside his clinical work, but some of his biggest breakthroughs have been his own: realizing how his privilege affects his worldview and helping others along the route to allyship.

HEATHER NYMAN, PharmD | (she/her)

Associate Professor of Pharmacy Practice and Assistant Dean for Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion at the University of Utah College of Pharmacy

Passionate about inclusive hiring practices, EDI education, and affordable health care

Heather stands on the Bonneville Shoreline Trail behind the Natural History Museum of Utah. An avid trail runner, this is her favorite place to unwind and enjoy uninterrupted views of Salt Lake Valley, a close second to the forests of her North Carolina childhood.

Tell us about yourself. How did your EDI journey begin?

I was in college when I first felt that I didn’t belong in certain spaces. Going through medical school and residency while feeling like an outsider, I was curious to understand why that was.

The first time I remember feeling like I belonged was when I interviewed for my residency in the Bronx. A majority of the patients I met identified as Newyorican (Puerto Rican from New York, like me).

Then I read a paper by Dr. Phyllis Carr and colleagues about the experiences of minority faculty in the US. I remember thinking, “It’s like they share my thoughts!” I’m not alone in this, the feeling of being foreign in a place where you’re born, of living in between. That’s what led me to study what equity, diversity, and inclusion looks like in academic medicine.

Living as an Arab Muslim in America with immigrant parents, my family felt that we needed to hide our cultural identity and assimilate in order to be accepted. They were concerned that being authentically ourselves was going to hinder us. And it did. My mom lost jobs because her accent was too thick. My dad and uncle anglicized their names after the oil embargo in the 1970s created less favorable feelings towards Arabs in America.

It was this “othering” that made it really uncomfortable to navigate spaces on someone else’s terms. I felt like I was never understood. My rebellion became trying to live authentically and allow those around me to live their truth as well. That’s the spirit of EDI I’ve tried to employ in my work over the years.

I’d describe myself as kind, passionate, energetic, a hard worker. I exhibit a lot of enthusiasm in my work.

When I was in my 20s, I worked in a few facilities as a nurse. I was often the only Black nurse at the facility, and I would look at how I was being treated by my colleagues and even by physicians. It struck me that we [people of color] were being treated differently. I started joining various committees that were focused on the betterment of the community as a whole—and not just in terms of EDI. At that time 45 years ago, no one was thinking about “EDI.”

As time went on, I worked and volunteered among different communities. I would talk with middle schoolers and teach cultural responsiveness at local hospitals. Once I joined my Master’s degree program, I really became vocal about making real change where I could.

The words I’d use to describe myself are very privileged ones: white, male, opportunity, a lack of barriers. I come at EDI from a world where I haven’t experienced many of the struggles that others have.

I wear my differences more on the inside than the outside. I'm a part of the LGBTQ+ community, which some people are surprised to find out when they meet me. I've had my own journey through that part of who I am, but, on the surface, I come from a very privileged background. I'm very grateful for the opportunity to work in the EDI realm because I feel a need to step outside of my own perspective and make the privilege that I've been blessed with available for anyone else who could benefit from it.

I’m originally from Brazil—born and raised, attended medical school, and moved to the United States in 2003. I’m an infectious disease physician by training, and the other hat I wear is medical education. I love teaching; when you teach, you’re constantly learning.

I got involved in EDI work about three years ago because I was living it. I identify most as an immigrant Latina, a woman, and a mother of two. I have been looked down on because I am not from North America, been seen as less professional because I am a mom, and felt like I didn’t belong in the workplace because I am a woman. That got me thinking, “This is not okay.”

Above all, people deserve the freedom and ability to be themselves. If patients restrain themselves from truly being who they are or feel like they don’t belong, that’s going to limit them from seeking access because they feel the available resources are not made for them.

I’m originally from North Carolina; my family’s always lived in the South, and I’m the first generation to leave. I’m a pharmacist by training and a divorced mom of three elementary-aged kids. I love cooking, trail running, and my favorite place on the planet is the forest of western North Carolina. That’s my happy place.

I’m passionate about people being seen as people. I’ve experienced bias myself: as a female scientist with a Southern accent and a divorced mom. There are a lot of labels and expectations that come with that. I look at our students and their experiences—the same way I look at my own kids—and I just want to make things in our little world better for them.

What barriers to access do you encounter most in your work?

One of the biggest barriers we have is that EDI work is not seen or valued in the same way as other types of work. Why? Most of the leaders in EDI are women of color, and can be the target of both racism and sexism.

In a similar way, the K-12 education system has always been underfunded and underpaid, because the majority of teachers are women.

We have leaders who acknowledge that we all have our place in this work. They understand the importance of EDI and understand that our progress as an institution as a whole has everything to do with it.

Unfortunately, librarianship in general—whether academic, medical, or public—is still an overwhelmingly White profession. There is some progress being made, but there’s a lot of work to be done. But I think something as simple as me showing up in these spaces and reminding people that there are individuals of color here makes a difference. My presence says, “Hi. I’m a multi-faceted, hardworking person. I’m not Christian. I’m not White. I celebrate a whole different set of holidays. Want to learn about them?”

Our biggest barrier, though, is the barrier to good information. There’s almost always a paywall to access articles, and that’s an obstacle for students and researchers trying to give the best care to their patients. Unfortunately, most journals are owned by large publishers who profit off of these paywalls. They’ve created a monopoly on good information. But many libraries are fighting for open access by covering publishing costs—over half of our operating budget goes to these costs. We also do interlibrary loans with other institutions to share the access we do have.

Librarians have a huge problem with misinformation because that content is free and readily available. If you’re sick, you’re not going to MedlinePlus, which is vetted through the National Library of Medicine in the National Institutes of Health. You’re going to WebMD or Healthline because it’s free, but you can’t be sure of the quality of advice you get. I teach an information literacy course where I ask students: “How many ‘health experts’ do you follow on Instagram? Do you ever check to see if they are a licensed dietician or therapist? How are you vetting the information they give you?” Just encouraging them to be more diligent about their sources.

Some of the barriers I see with our students, especially students from rural or underrepresented areas, is finding support once they’re in college. Some guidance counselors at high schools won’t tell the students about the various programs that are available through the U, and then they don’t find out anything until they get here. They [counselors] don’t take the time to sit down with the students to assist them with the nuts and bolts related to applying to colleges. Because the students are from certain communities, they consider helping them a waste of time, while other students are told about funding, resources, support programs.

When I run into pre-nursing students on campus, I ask: “Do you know we have an early assurance program? What about our needs program?” And they had no idea this program existed. Efforts have been made since then to better inform pre-nursing students that this program is available.

That’s a systemic barrier; another barrier is financial. These students may only have enough money for tuition, but not to buy textbooks or a computer. These resources are available through the Eccles Health Sciences Library—so much at their fingertips that could help with their scholarly projects or assignments that would make their experience easier. I recently asked a nursing class about to graduate if they were aware of this asset, and most didn’t know. Imagine how much that information might’ve helped them while they were students early on. These are barriers in the system that don't need to be there.

The last barrier is personal. Many students from underrepresented groups feel they don’t belong and aren’t good enough to be in our program. I was 43 when I went back to school, so I know how that feels. But when someone believes in you and tells you that you are good enough, it makes a world of difference. The support from faculty can be an immense help to students.

From my experience, there are three major barriers: geographic, financial, and cultural. We know that there are segments of our population, like rural patients, where physical access to dental services is difficult. Then there’s the ability to pay for and afford our services. Finally, there’s the cultural barrier. Many of our community members don’t feel comfortable entering into and being part of our health care system. They may not understand how it works, or they struggle to trust our providers.

From a provider’s perspective, it’s easy to think all we have to do to broaden access is open the doors and they will come. But we have to create the cultural awareness and knowledge among our own staff and meet the people we serve in a space that they feel safe in. We need to create an environment where our space is their space. In the medical community, within our institution, and even within the School of Dentistry I'm seeing that our providers (and our students especially) are working to make care more accessible.

Our culture as a whole is not going to advance unless everyone advances. We're all in this boat together. I've been lucky to have access to the services I needed along the way, so opening that opportunity up to everyone is an important part of what I do.

I currently practice at University Hospital where we provide care regardless of ability to pay. I've not always worked in settings like that. The main place where I see disparities here is in what people have access to before they come into the hospital and what we can send them out with after leaving the hospital. But while they're in the hospital, there are drastically fewer inequities, which is a wonderful place to work.

Money is one barrier, especially when it comes to health insurance. There are also language barriers. As an immigrant, I am privileged to speak English fluently, but for many that is not the case. The ability to be fully understood when we seek care and not be misjudged because of cultural norms is absolutely necessary.

Here’s an example. As a Latina, we are very physically expressive people. We hug and kiss when we greet each other. And because of this, some people blamed us for passing COVID-19. They don’t understand that physical contact is important to us. We also tend to live in large households with multiple generations. That’s part of our culture—we care for our elders and our children together, and that’s often looked down on without people understanding the reasons behind it.

What projects or initiatives are you most proud of?

We do really great work in the EDI space, and one of our proudest accomplishments is the academic research we publish, because it legitimizes the work we do.

One paper I’m very excited about is how we contribute to the diversity of our graduate programs through our K-12 grade outreach and our Future Doctors program, which is for 9-12th grade. We’re about to publish the outcomes of this research, which show that half of the students in these programs identify as White.

Bottom line: We’re increasing diversity in our graduate programs, without excluding those who identify as White. This means that all types of students are benefitting from this outreach work, and that really shows the success of our programs overall. EDI work isn't a zero-sum game—when one of us wins, we all win.

My first goal was to change the part-time desk staff positions to increase diversity and reduce our turnover rates. We started by changing the job description to focus on how student applicants would stand to benefit, rather than what we as an employer need. It included questions like: “Do you like working with people? Do you want to build research skills? Do you want to play with technology like 3D printers?” We think of it as a partnership where we can help them grow.

Since we changed the description, staff went from staying just one semester to an average of 2-4 years. And they came from more diverse backgrounds too—from different racial groups, studying in different majors—because they saw themselves as a valued part of the library before they even applied.

We work hard on retention. I spend a lot of time cultivating good relationships and being amenable to things like school schedules and final exams, because their education has to come first. This phase of their life is so complex—they’re juggling newfound independence, school, a job, relationships, a social life. I give them a lot of grace.

My other achievements are relatively small ones… providing free menstrual products in all bathrooms, becoming a distributer of Naloxone kits so medical students or professionals can have them on hand. The little things matter, though. They can see the library as a resource outside of education where they can ask questions and request things they need. That’s huge.

One of the programs we’re working on is revising our curriculum. We talk a lot about language: What type of language are you using with patients? How do you talk to patients about various disease? Are the pictures in our textbooks representative of different groups? Is the wording inclusive? Are case studies diverse?

The other project is developing student belonging. I don’t know what that’s going to look like yet; we’re in the process of collecting data. But our goal is to make sure all our students feel that this is an inclusive space for them, that they belong and are safe.

We’ve also received a nursing workforce diversity grant that’s helping us develop health care providers, specifically nurse practitioners, in rural areas. And we have a program to elevate certified nursing assistants (CNAs), especially CNAs of color, to go back to school and get a registered nursing (RN) degree.

We expand our operations and clinics into rural communities in Utah to make access to dental care easier. But we also bring rural students to the School of Dentistry to study and return to those areas. What better way to break down those barriers than to send practitioners that are part of those communities back to serve their neighbors?

We are a huge Medicaid provider, and many of the patients in our clinics are from underserved backgrounds. That’s the second part of our mission. Dentistry has been a White male occupation for decades, and we're trying to change that vision and dynamic of what dentistry is in Utah. By providing those pathways to bring people in from underserved backgrounds and rural areas, we can educate them and get them back out into their communities.

What we're really trying to do is create an institution where everyone in our community feels safe and knows we're going to provide the care that they need in the space that they need it. Part of becoming self-aware in EDI is realizing that my perspective is only my own. The way the world looks and exists is totally different for others.

I’m very driven to increase minority representation and create an inclusive environment. Raising awareness that there is a shared responsibility when it comes to equity, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace is one of my most important initiatives. It is not the responsibility of people of color to make White people understand this.

I also recently created an EDI Leadership Group that has representatives from every department in the School of Medicine. This engages people from surgery, genetics, and every other department to be representatives and carry on with EDI work in their space. EDI has an impact on everything we do because our efforts are about the population that we serve, and we serve a diverse population in every department.

The only way EDI initiatives are going to advance is if everybody understands it is their responsibility to advance it. It’s moving slowly, but it is moving—and that’s my mission. The day people embrace this shared goal, my work is done.

What’s the most fulfilling part of this work for you? The most frustrating?

First and foremost, I do this work to make Utah and the U a better place for my children. That’s my “why”. But when I lose that spark, what keeps me going is that I get to write about and share powerful stories about the great decisions our institution often makes.

Here's one example. During the pandemic, we didn’t want any people to miss paychecks or lose their jobs. So, the people who got paid the most took temporary pay cuts to ensure this wouldn’t happen. It wasn’t guaranteed that we’d ever get that money back, but people signed up to cut their pay anyway.

That was a real equity-based decision, because it benefitted the people who are paid the least in our institution (which unfortunately is also the most diverse group). It also shows we’re focused on making things better for our own, the people who already work here, and improving their circumstances through initiatives like job pathways and promotions. Moments like these keep me going.

For me, it's the administrative aspect: all the policies, procedures, paperwork. I just want to get out there and do the work! By far the best part is seeing the product of it all. Starting with an idea, getting everyone together, gathering what we need, and seeing that process come to fruition.

Even as I call it frustrating, there’s a real value in it. When I started in this position, I depended on the documentation provided by those before me, and the policies we create will continue to live on in the culture of the library. In 10 years I may not be here, but I’d like to believe I’m setting the groundwork for the next leader to build upon.

The best part is the momentum we have in the College of Nursing. I can’t say everyone, but most are so committed to this work: students, faculty, and staff. My colleagues are very supportive and want to see changes happen. Everybody wants to see what we can accomplish. I call us a multicultural melting pot.

The frustration comes when our work is siloed and people don’t tell me what they’re working on. It’s hard to give feedback or help promote programs when I don’t know about them, but we’re working on that.

It’s also difficult when people think you’re not doing anything or working fast enough. I tell them, “Come on into my office and let me read you the list of what we’re working on.” Then they understand—these projects just take time. They can be exhausting and very emotionally draining.

The denial. Many people still deny that racism exists; they believe that everyone has the same opportunities. It’s absolutely inaccurate and the result of privilege.

Though it is frustrating to deal with ignorance, EDI work is also very humbling as it has allowed me to see gaps in my own knowledge. I get put in my place regularly when I realize there are things about other communities that I understand nothing about.

It’s hard to hear that you did something wrong, that you offended someone. Even people who do EDI work can be wrong all the time. It’s painful, but it helps you grow. Those mistakes have made me more aware of EDI issues in my own life—like hearing two female interns being called “lovely” when a male intern wouldn’t ever be called that, or my daughter’s school asking to put my email on their “whitelist” so their messages wouldn’t be sent to spam. (Who still uses “whitelist” and “blacklist”?) I become more aware every day and I’m growing from it, which is very satisfying.

Across both my patient care and teaching experience, I’ve realized that there are highs and lows. The highs are usually meaningful, individual experiences, and the lows are when the bureaucracy makes you feel like you’re not being efficient or making progress. I’ve learned to ride those waves, knowing that it fluctuates.

One of the hardest parts of this work is seeing the big picture. It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the details, so stepping back and looking at the whole picture helps when you need to adjust your focus. Even as I say it, I get lost in the details all the time. But you can always step back and say, “These are the people. This is the work. This is what matters.”

How has this work impacted your perspective? What lessons have you learned that you’d pass on to others?

I’ve worked in this space for quite a long time and one of the things I’ve learned is that this work fails in isolation. If you expect all of the equity work to be done by the EDI office, you’ll have people turning over and not wanting to stay because the physical and emotional toll is too great.

Don’t try to do this work alone; create strong connections and allies. That’s what we’ve done by having champions in every division, every department, every unit. We do this work together.

My second lesson is to write about what you do. There’s no substitution for this—the work you do gets systematized quicker when you write about it. When we show the impact of EDI work in peer-reviewed journals, it means it has scientific merit. That’s powerful. It shows this work makes life better for everyone in our community. It’s also healing to write. This work is hard, and it hurts a lot.

First off, be patient with yourself. I tell myself all the time: I’m doing this. I’m holding my own. I’m doing a good job.

There’s no template or rulebook for this kind of work. I’m the inaugural associate dean—I don’t have any footsteps to follow here. We can’t ask the last person how they did it, or how we can improve on their work. We’re building the track as we ride it.

Second: make your process sustainable. Ground yourself in the knowledge that these are not “one and done” projects. When I retire, someone’s going to have to pick up this work. I’m not going to be here forever; I have too much I want to do! So, I need to plan for the next leader. Who’s going to take my place? How can I prepare them and mentor them for the job they’re taking on?

Try not to be defensive; it’s the immediate instinct we all have. Also, understand the difference between intent and impact. Of course, your intention wasn’t to offend someone, but you did. Don’t try to justify your actions with your intentions. Try to learn from it, grow from it, and do better next time. Be open to learning and to changing.

It’s been eye-opening. This society, this country has been entirely built for men like me, but we’re socialized to believe this is normal. EDI work is about creating a paradigm shift. In addition to breaking down barriers and widening access, our other pillar is changing the core thoughts and beliefs of people with privilege in our system.

Privilege comes with a responsibility: to help others, to understand others. You’re going to feel some shame. Let yourself feel it. Lean into it, shed the tears, cleanse your soul. It’s a lifelong process—I don’t think there will ever be a point where White people can stop that introspection, and that’s okay. It’s not about a destination but about putting energy and effort into regularly stepping out of our own experience.

It’s enabled me to look at how I provide care and how I interact with the people around me. As an educator, I’ve loved working with students to help them see and understand the perspective of those that are walking through our doors, that not everyone engages with health care the way they have. It's that ability to step back away from yourself, finding that place where you can both meet to make it really beneficial for the patient. At the end of the day, that's what we're in the business to do.

What’s your vision for the institution in five years’ time? What change would you like to see?

I want to work myself out of a job. Here's what I mean: I want the work our office does to be taken over and owned by each individual team and the individuals within it. I want titles like mine to end because everyone is incorporating equity work into what they do.

Five years from now, I’d like our medical school to reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of Salt Lake, to have diversity on the front lines so that people feel heard and can communicate with their providers, and to see diversity at the highest levels of leadership at U of U Health and the University of Utah as a whole. And that diversity is more than just gender or race—it’s about hiring veterans, immigrants, people who are passionate about equity work.

It’s about finding community. It’s a struggle sometimes, but this is where we find belonging—when the people who are not exactly like you embrace your differences.

I want people to come here, feel they belong, and get encouraged to be their best. I want us to think about health a little more globally—to strengthen our partnerships with other community organizations, connect with local lawmakers, and help enact change that makes for more equitable health care.

We’re going through the biggest social justice movement of our lifetime, so we all must use it as an opportunity to gain momentum.

Personally, I would like people to feel like they that they are, in all senses, included. Humans have a tendency to think in terms of “us” and “them.” It should be “we,” period. My goal is for people to feel that no matter their identity, they belong here.

Equity is for everyone

Story and concept by Nafisa Masud

Design:

Luat Nguyen

Jesse Colby

Photography:

Louis Arévalo

Niki Chan Wylie

Kim Raff

As part of our commitment to equity, diversity, & inclusion, U of U Health sought out and supported the services of BIPOC photographers for all photoshoots featured in this story.

Production Support:

Amy Albo

Nick McGregor

Stace Hasegawa