FOR THE LOVE OF MOTHERS

Amid the pressures of parenthood, many Utah mothers struggle with postpartum mental health. In our family-friendly state, are we caring for the caregivers?

Disclaimer: This article mentions mental illness, suicide, and other sensitive subjects, which may trigger negative thoughts and feelings for those currently experiencing or still recovering from a mental or mood disorder.

Few human experiences bring a wilder wave of clarity and chaos, purpose and doubt, deep fulfillment and new fear than motherhood. As the joys of parenting evolve to meet each new phase, so do the struggles.

On top of stress, sleep deprivation, and rebalancing hormones, many mothers feel huge shifts in their sense of identity and a pressure to be perfect at the very moment their lives have been thrown into disarray. Despite these changes, they’re often expected to keep up with everything they already do as partners and workers. Generations of families don’t always live near one another, removing key pillars of the “village” that it takes to raise a child and making motherhood feel more isolating. Social media often erodes community even further, applying new expectations that make it harder to be vulnerable. And once COVID-19 hit, some of the learning, child care, and work moved into the home, adding to a growing list of responsibilities.

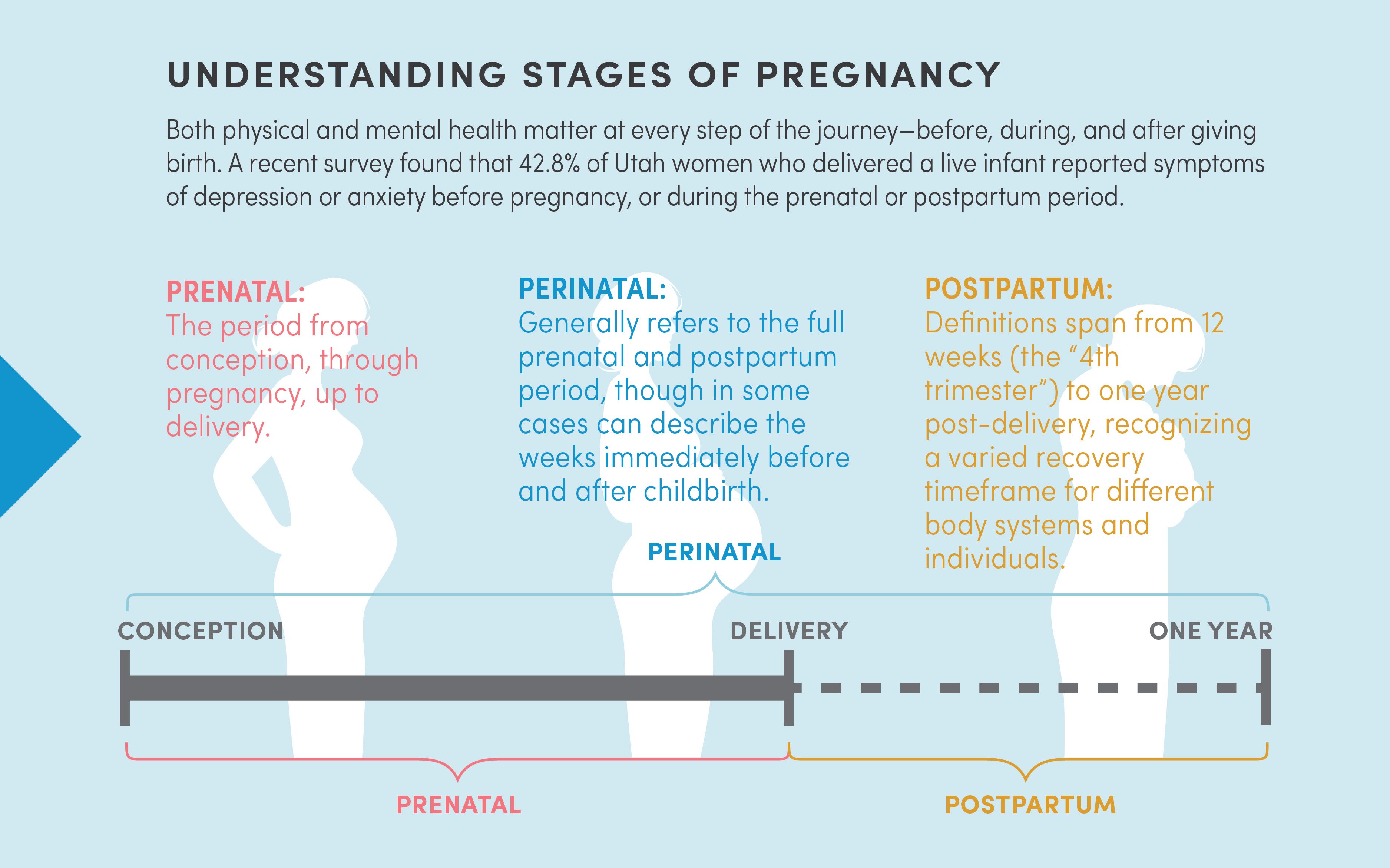

Is it any surprise, then, that depression, anxiety, and stress are often quick to follow? In fact, one in five women in the United States suffer from perinatal and postpartum mood disorders. These conditions, occurring throughout birth and up to a year after delivery, are startlingly common—more common than preterm birth, diabetes, even high blood pressure.

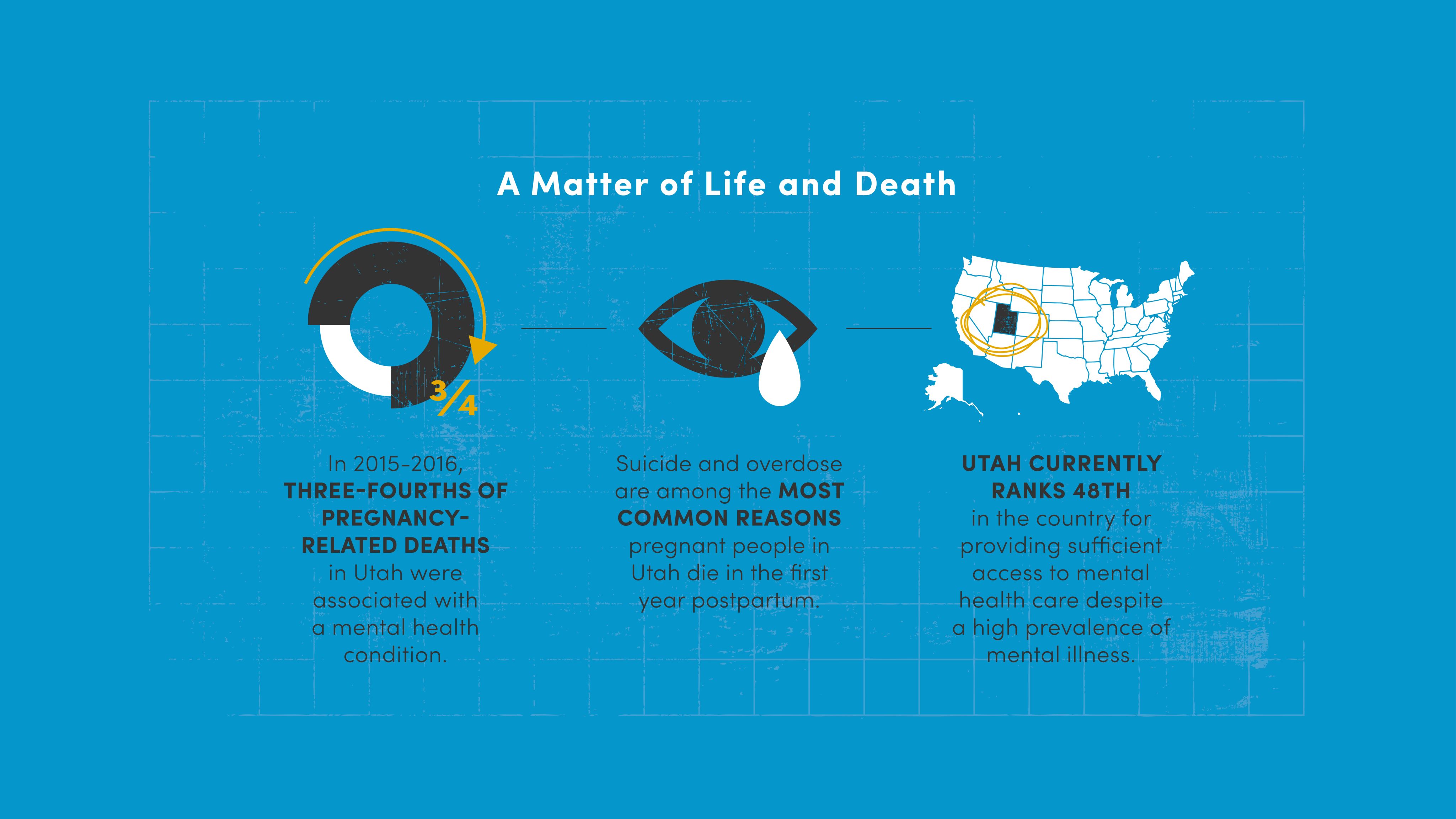

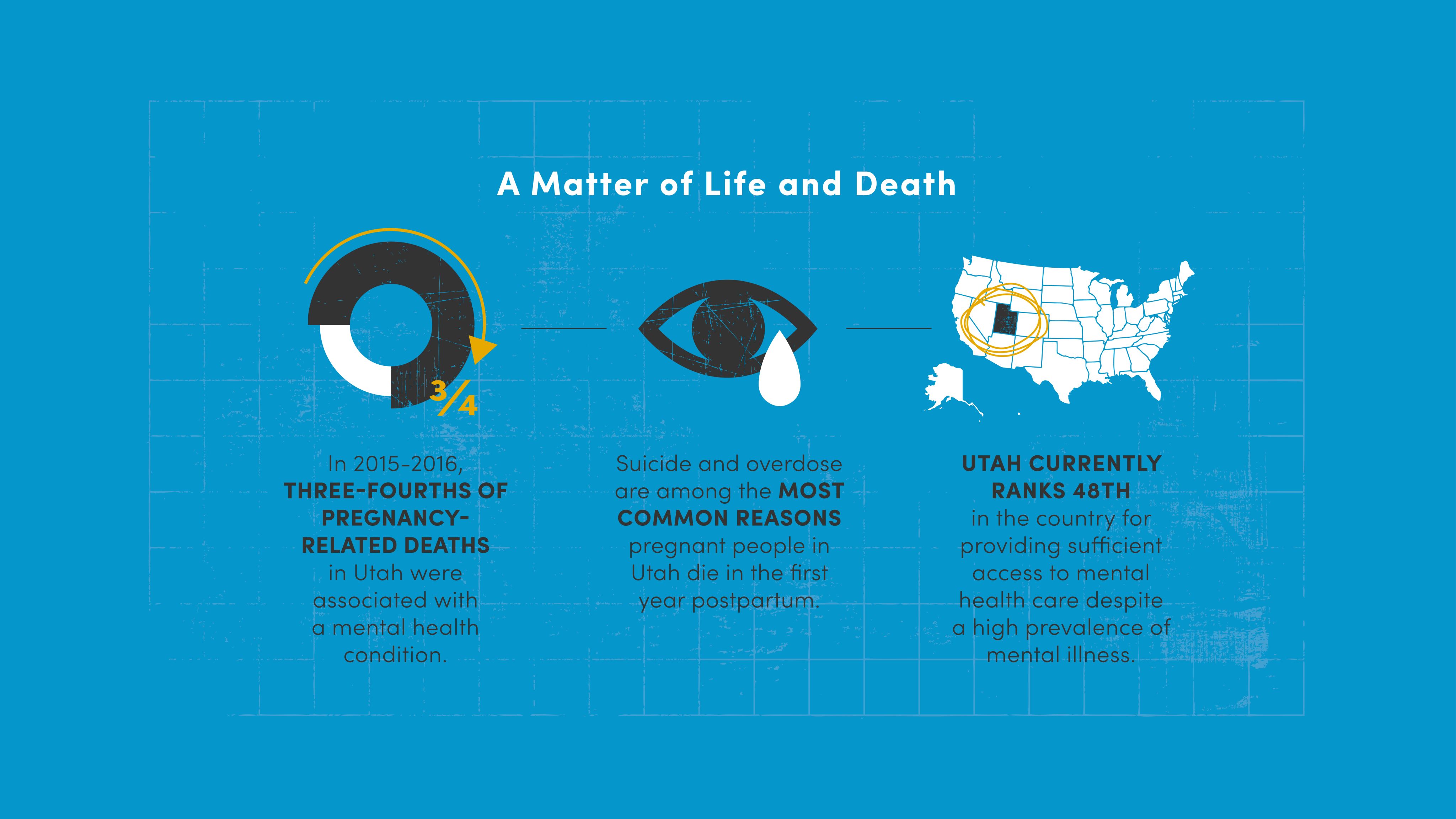

This is about more than psychological struggles. From 2015 to 2016, 75% of pregnancy-related deaths in Utah were associated with a mental health condition—and many of them were preventable. “Until 2022, in 14 states including Utah, suicide and overdose were the two most common reasons women died in the first year postpartum,” says Jamie Hales, LCSW, clinical manager at Huntsman Mental Health Institute (HMHI) and board co-chair for Postpartum Support International Utah.

Left untreated, postpartum mood disorders can also affect a mother’s bond with their newborn, personal relationships, ability to work, and family as a whole. In the worst cases, postpartum depression and psychosis can result in tragedies that impact entire communities. As we wrap newborns in the care they need, it begs the question we don’t often ask: Are we taking care of the caregivers? Not just for their physical well-being, but their mental health. And not just for the nine months of pregnancy, but also after birth until they feel fully recovered, recognizing that looks different for each individual.

The truth is, for those who haven't experienced postpartum depression, it's hard to imagine what it feels like. There's the crippling anxiety, the pressure of perfection, the hopelessness. To really understand it, we must turn to those who know postpartum depression most intimately: mothers. The Emily Effect Foundation recognizes the importance of sharing these stories. Founded in memory of Emily Cook Dyches, the Utah charity is committed to raising awareness and coordinating mental health resources for those who need it. Below, Utah mothers generously share reflections on their postpartum experience as part of the "Letters of Light" movement.

ASHLEE

"I never could have imagined the intense love I would have for each of my children. But along with that love came a deep and intense feeling of anxiety. I felt an overwhelming responsibility to protect each child from everything, even a small cold.

This anxiety started to control everything I did. I stayed awake at night worrying about every sickness or sniffle that might be going around, and what would happen if my child contracted it. Even though I knew in my rational mind these stories weren’t true, I couldn’t turn my brain off. I would wash my hands until they’d bleed trying to protect my children.

I hid so many of my fears from everyone around me. I didn’t want people to think less of me.

With a lot of support from my husband and time, my anxiety lightened. I can’t help but wonder how much more peace I could have had during those amazing years if I would have had more professional help."

KYLEE

"I was diagnosed with severe postpartum depression about 4 months after my second daughter was born. With a 2-year-old and a newborn, I felt exhausted, overwhelmed, and defeated all the time. I didn’t want to get out of my bed–even the simplest tasks like getting my girls dressed seemed hard and overwhelming. I just wanted to sleep all day.

I felt super anxious about small things, such as leaving the house. I would worry about little things like, 'What if I’m at the store and the baby starts crying? What will I do? What will people think of me?' I started to have intrusive and suicidal thoughts; I felt ashamed for even thinking these things. I had a great, helpful husband and two beautiful, healthy little girls. How could I be so selfish and have such dark thoughts when I was so blessed? This wasn’t at all what I signed up for or thought motherhood would be like.

After seeking help and finding the right medication, I could finally see the light at the end of what had been a dark, seemingly endless tunnel. I had hope again. I started to enjoy my girls again. I enjoyed being their mom and soaked up everything good life had to offer me. I felt more spiritual connections and had immense gratitude towards those who had pulled me through those hard weeks.

If you’re battling postpartum depression, I see you. You aren’t alone. I know it hurts and it’s unfair, but you can get through this. You are so much stronger than you think. Your baby needs you, and only you. Fight and get the help you need for them. I’m here, cheering you on."

RACHAEL

"I remember crying as I held my daughter, wondering if putting her up for adoption would make me a bad person. I also remember that when she cried during those first weeks, panic would shoot through my body. I can only describe it as being afraid of her.

My daughter had colic and didn’t sleep well, which exacerbated my own symptoms because of the sleep deprivation. I felt inadequate and like a failure. Women had been having babies for all of existence, and I couldn’t handle one? What was wrong with me? I soon found myself a psychiatrist and went on medication.

My advice to other struggling moms is to get help – it’s there. Confide in someone, regardless of the embarrassment, because there are greater things at stake. If you can, do things for yourself that you would do for a loved one going through the same thing. Don’t isolate yourself. Things may feel hopeless, but it’s simply not true. Let time be a healer. You will sleep again. You will feel joy again. As time passes, we grow, learn, adapt, and find balance. You are the perfect imperfect mother for your child. Just hold on."

LISA

"I fought postpartum depression after the birth of each of my four children, but after my daughter Clara was born in 2013, I nearly didn’t make it back to life and health. Clara’s birth was a high-stress emergency C-section with multiple complications. My husband feared he would lose us both.

Luckily, we both survived, and thought we were through the woods with the promise of sunlight ahead. But the deeper threat came later; during the long months of a bleak winter, I became more isolated and depressed. I cried every time I was in the shower, as the sound of the water masked the sounds of my sobbing.

I truly thought that my family and my new baby would be better off without me. I had been on antidepressants before, but I had stopped taking them because I thought I was okay without them. I was wrong.

I finally admitted my dark thoughts to my mother and husband. My mother was my lifeline. She called me several times a day and stayed on the phone with me for hours. I went back on medication, and my husband took the night shift with the baby, because the dark hours before dawn triggered my anxieties the most. Eventually, spring came and thawed my heart. It was like waking from a restless nightmare. I started to find joy in simple things–such as a bouquet of dandelions from one of my kids.

Slowly, I came back to myself, with the love of my family, medication, and walks in the sunshine. I am so grateful for my life. I am so glad I stayed to mother my children. There is help and light and hope ahead for you. Don’t give up."

When seeking postpartum health care, Utah mothers can face a host of barriers. One is geographical: In rural Utah, access to general health care is a consistent challenge. “We have one or two pediatricians here in Carbon County; in Grand County, there’s two dentists,” says Sara Braby, RN, director of nursing for the Southeast Utah Health Department. “From Moab, patients go to Colorado sometimes to get health care. We just don’t have the options like other places do.”

Sara Braby oversees nursing for the Southeast Utah Health Department, which offers health care to many rural Utah mothers.

Sara Braby oversees nursing for the Southeast Utah Health Department, which offers health care to many rural Utah mothers.

Finding a local mental health provider is an even greater challenge. Only 143 mental health providers in the state’s database have specialized training in perinatal mood disorders. For a state that counted 46,000 live births in 2021, and whose birth rate regularly tops the national average, that's just not enough. Mental Health America ranks Utah 48th in the U.S. for providing access to care amid a high prevalence of mental illness. And experts from the Kem Gardner Policy Institute estimate that Utah must more than double its mental health workforce over the next 15 years to adequately address these growing needs.

This issue is exacerbated for women who identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC). They’re more likely to be uninsured and face barriers to adequate health care overall, increasing the rates of pregnancy-related complications and a death rate that is 2-3 times that of White women. For undocumented mothers, who are not eligible for Medicaid, often their only contact with the health care system is when they arrive at an ER to deliver their baby (which is covered under Medicaid’s emergency services). For any prenatal care, including mental health care, they’re left to seek out community health resources, often at a cost.

Mental health providers of color are also considerably harder to find than White providers. Utah Department of Health and Human Services' Maternal Mental Health Referral Network lists only two psychotherapists statewide who specialize in treating BIPOC clients. That cultural responsiveness—the ability of a provider to understand the unique pressures and experiences affecting a patient—is crucial. BIPOC mothers regularly experience discrimination while seeking care, their concerns often dismissed and necessary tests and interventions denied. This inequity in treatment can have lasting, and devastating, implications for their well-being.

Utah’s often touted as a family state—safe, with good education and ample resources. Indeed, we consistently rank among the highest birth rates in the U.S. But in a state so family friendly, why are Utah mothers being left to fend for themselves? Are we really valuing families if we’re not fully caring for the people at the heart of them?

Braby is especially focused on expanding depression screenings at regular care appointments and providing accessible care where patients feel seen. "Communication goes with culture," she says. "If patients speak with somebody that speaks and understands their culture, they're more apt to receive services."

Braby is especially focused on expanding depression screenings at regular care appointments and providing accessible care where patients feel seen. "Communication goes with culture," she says. "If patients speak with somebody that speaks and understands their culture, they're more apt to receive services."

A LIFELINE FOR NEW MOTHERS

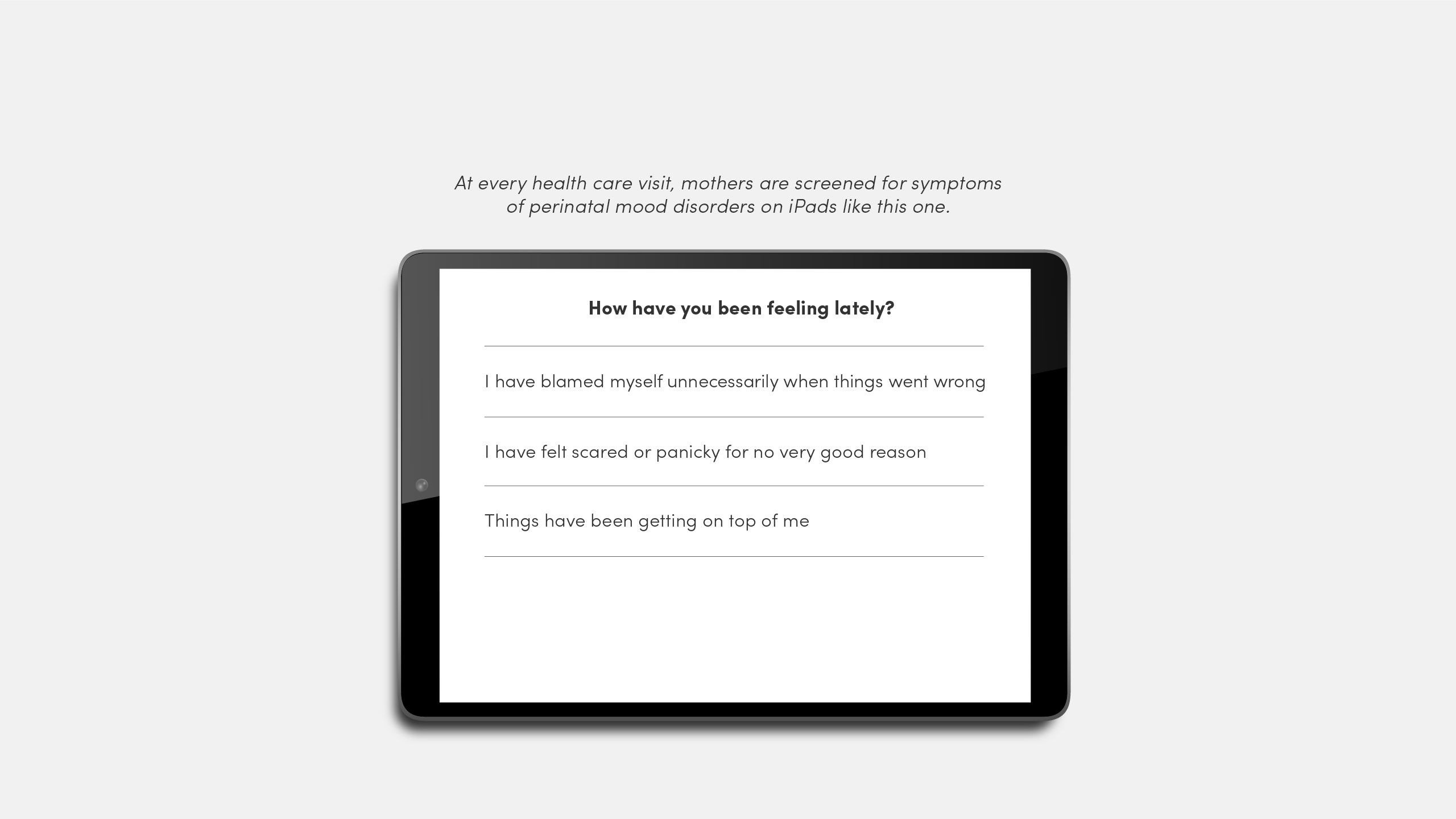

The first step is to identify who is struggling, and that starts by simply asking mothers how they are doing. In 2016, Gwen Latendresse, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN, associate dean for academic programs at the University of Utah College of Nursing, built a program to screen women for perinatal mood disorders at all pregnancy and postpartum health care visits in U of U Health’s system and at Utah’s public health clinics, including Braby’s clinic in Price. “At first, a lot of moms thought that we thought something was wrong with them because we were giving them the screening,” Braby says. “But in the years that we’ve been doing this now, it’s really become more normalized.”

The Utah Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) partnered with Latendresse’s team to increase access by providing the depression screening on electronic tablets in clinics in several rural health districts across the state. Patients complete a 10-question survey that asks how often, in the last seven days, they’ve had certain feelings—for example, “I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things,” “I have been anxious or worried for no good reason,” or “I have been so unhappy that I have been crying.”

When you ask someone how they’re doing, you have to be ready to hear their answer. If a woman’s score on the screening shows symptoms of a perinatal mood disorder, a clinician reaches out with additional resources, usually within 24 hours. Given the scarcity of mental health providers statewide, DHHS has also created a toolkit to train primary care providers to screen patients themselves. It’s about educating not just mothers, but providers, too.

The goal here is to make getting help easier, allowing mothers to seek mental health support in the same room where they receive physical care.

Screening for perinatal mood disorders tackles one of the most obstinate barriers to new mothers getting help: it's difficult to talk about. “Stigma has been a challenge both within the hospital setting and outside,” says Teresa Lopez, LCSW, director of behavioral health integration at U of U Health. “We want to provide behavioral health services within women’s health. That idea itself was challenging for [many] years.”

And for good reason. It’s hard enough to ask for help, let alone after what most consider the “miracle” of childbirth. But the work of Latendresse, Lopez, and others focuses on this truth: Motherhood has never been that simple. There’s immense joy, as well as pain. It’s normal to feel this way—and it’s treatable.

Now, Lopez works with more than 30 social workers who cover nine primary care community clinics and 26 outpatient specialty clinics, mostly based out of University Hospital. Three of those clinics specialize in overall women’s health, and another two are SUPeRAD (Substance Use in Pregnancy Recovery Addiction Dependence) clinics, providing mental health care to pregnant and postpartum individuals who need recovery or addiction support.

“Mental health services should be a component of prenatal care and postpartum care that's just integrated. It’s seamless, it's there, it happens.”

-GWEN LATENDRESSE, PHD, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR FOR ACADEMIC PROGRAMS, UNIVERSITY OF UTAH COLLEGE OF NURSING

BRINGING CARE CLOSE TO HOME

So, what resources are available when a mother shows symptoms of depression in these screenings? Getting them the help they need, especially during the pandemic, demanded a new approach.

That’s where telehealth came in. Latendresse developed two studies offering telehealth support groups for rural Utah women who showed symptoms of perinatal depression. The groups met online for 10-12 weeks at a time. Because they were run by master’s students being supervised within HMHI, there was no cost to the patients.

Even before these most recent studies, Latendresse had started using videoconferencing to offer more accessible care. Convenience was key: Where there aren’t enough mental health providers, offer care to groups of women. When pregnant individuals and new moms don’t have the time, energy, or resources for in-person appointments, make care virtual. Even women in urban areas, her team found, often didn’t have the child care or transportation needed to get to in-person therapy sessions.

The jump in participation was immediate. “If women were away on vacation, they could stop for an hour and join the group,” Latendresse says. “They could join on their lunch break. They could cook dinner while attending or join for an hour after the kids went to bed at night.”

“What I’d love to see is that all women have access to information, education, and risk assessment,”

Latendresse adds.

“Then, if they do develop perinatal depression, they have easily accessible resources: mental health professionals that they can get in to see quickly and medications that are accessible. It should be as easy as walking in and getting prenatal care.”

“Women should get good preventive care so they don’t even end up with any kind of a mental health condition,”

says Gwen Latendresse, PhD. Group interventions and around-the-clock virtual access can provide mental health support to mothers exactly when they need it—with the comfort of anonymity.

ADDRESSING SHAME AND STIGMA

Latendresse’s studies use mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy (MBCT), a treatment that blends cognitive therapy with meditation and mindfulness for those wary of taking medication. MBCT can help interrupt the spiraling feelings of shame, guilt, and self-criticism that affect many mothers with perinatal mood disorders—often believing they aren’t good parents or shouldn’t feel as sad as they do.

Sarah McCormick was no stranger to this shame. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in her early 20s, McCormick had been put on medication with depression as a side effect. But the birth of her first child in 2013 brought on something new: severe postpartum depression, more disabling than what she’d experienced before.

“I’d have lots of fatigue, no energy. I’d find that I just feel really numb,” she says. “Everything feels like a chore. And everything feels heavy. You can’t find the good things and the joy in life.” When the same thing happened after the birth of her next three children, she sought counseling at some times, medication at others. Mostly, she was resigned to a new, darker outlook and put a lot of blame on herself, saying, ‘Well, unless I’m willing to eat 100% right and exercise, and make sure I’m getting sleep… [depression] is just going to be my lot in life.’

After her daughter Amelia’s birth in 2020, McCormick joined Latendresse’s program and was stunned to feel immediate results. “When I combined medicine with this program, it finally was like, Oh! This is the ticket.”

Sarah McCormick with her family, May 2023.

Sarah McCormick with her family, May 2023.

The telehealth group not only interrupted McCormick’s circular negative thinking but helped her find others with shared experiences. “It normalizes it; you don’t feel as marginalized,” she says. “You can feel like you are part of a community.”

Because these groups were available to women across Utah, they also offered some anonymity, which helps with that powerful social stigma about mental health.

“We live in a small town. If you don’t know someone directly, you know somebody that knows them, and that’s a worry, if women don’t want to talk with people that know them or their family.”

-SARA BRABY, RN

Thanks to these regular screenings, mental health is becoming a readily more common topic in patient visits. "We're super proud of the progress we've made," says Braby. "We have a lot of moms that say, 'This is what's going on with me; where can I get help?' Now, it's become a part of the visit—like, 'Let's take your blood pressure, let's do your temperature, your depression screening was this number, let's talk about it.'"

Accessibility, affordability, community, just enough anonymity. The groups worked: Women in Latendresse’s first study group had much lower depression scores, even six months later. When participation dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic, Latendresse’s team pivoted again and developed a suite of on-demand mental health resources, connected to U of U Health’s web-based YoMingo® patient education platform. Women could browse resources at their convenience. Interestingly, most users log on at 9 pm (once kids are in bed) or 3 am (when moms can’t sleep).

Programs like these enshrine a vital truth: While postpartum recovery looks different for every mother, each deserves a community they can rely on, exactly where and when they need it.

SUPPORTING MOTHERS AT EVERY STAGE

For those feeling lost in or overwhelmed by motherhood, telehealth is an important lifeline to stay afloat. But that’s a drop in the bucket. What’s needed next is extended support through the postpartum period.

Currently, 40% of U.S. births and 22% of Utah births are covered by Medicaid through a federal mandate that covers prenatal and perinatal care for mothers, but only until 60 days post-delivery. After this point, mothers must qualify and re-apply for coverage through other Medicaid programs, where eligibility is determined by the individual state, leaving many mothers to fall through the gaps.

Applying for Medicaid is not easy. Eligibility varies by program, and coverage is not guaranteed. But it can be well worth the effort. Consider this: The federal poverty level for an individual is $14,580. The average U.S. birth costs between $10,000–16,000.

These issues existed long before COVID-19, too. A recent Health Affairs article found that among prenatal Medicaid enrollees who lost coverage in the early postpartum period, two thirds remained "consistently uninsured" at nine and 10 months postpartum. So, alongside new adjustments to parenthood—the stress, sleep deprivation, and physical recovery—mothers are often tasked with conducting research, submitting applications, finding new providers, and enrolling in a new plan, all in the hopes of continued coverage. Motherhood certainly doesn’t end at delivery, and it doesn’t end 60 days after.

In April 2022, Medicaid offered some relief. Through a new amendment, each state could choose to extend their postpartum coverage to a year post-delivery. By December, 27 states had approved extensions; eight other states were in the process of implementing their own. Utah joined them with S.B. 133, a bill passed in March 2023 that modified Medicaid coverage to cover a full year postpartum with some restrictions.

S.B. 133, sponsored by Utah State Senator Wayne A. Harper, MS, offers many Utah families much-needed support. “If mothers and newborns don’t have quality of care in that first year, it can affect them for a long time, even throughout their life,” Harper says. “We’ve got to realize that people have a variety of experiences with childbirth. If you work for a good company, have good insurance, family and social support, that’s great. But sometimes you don’t. We need to make sure everybody with a newborn has the safety net they deserve.”

Though not a complete solution, bills like these are a vital step toward better care for mothers. “This is something that Utahns actually are paying attention to,” says Utah State Representative Rosemary Lesser, MD, also an OB/GYN. “Our health care systems are also paying attention to this; the University of Utah has really led out.” Lesser was the sponsor of H.B. 220, another Utah bill that—though it did not pass—raised vital awareness about the urgent need for extended postpartum coverage. “When I would be caring for women under Medicaid, we would be scrambling to accomplish our health care goals by 60 days,” she says. “That’s what informed my presentation of this legislation.”

Progress is on the horizon at a national level, too. Earlier this month, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first oral drug for postpartum depression. A once-daily pill taken for 14 days, Zurzuvae can be conveniently taken at home and acts much quicker than other antidepressants (which can take weeks or months to take effect). Though not a cure-all, especially considering the many factors that can cause postpartum depression, this medication can support mothers during those crucial first days following childbirth.

The message all this work sends is simple: Mothers matter. With broadened access to care, new interventions, and insurance coverage through every stage of pregnancy, the goal is healthier, happier parents and babies across the state. Telehealth groups, universal screening, integrated care, and a stronger safety net are some of the best tools we’ve got to get there.

Additional Resources

If you or someone you know may be struggling with perinatal/maternal mental health issues, you can find a provider through the Huntsman Mental Health Institute. For a list of local agencies and support groups available, visit Postpartum Support International Utah.

Sources for all data within this story can be found online.

FOR THE LOVE OF MOTHERS

August 11, 2023

Story by Aliyah Baruchin and Nafisa Masud

Design:

Luat Nguyen

Jesse Colby

Illustrations:

Dung Hoang

Photography:

Niki Chan Wylie

Vianney Alcala

Editor:

Nafisa Masud

Publisher:

Amy Albo