SECOND CHANCES

When COVID-19 ravaged Manny Arocha, science and medicine fought alongside family and faith to save his life.

This story contains graphic images and videos of a COVID-19 patient in the ICU.

A week after Manny Arocha tested positive for COVID-19, his wife LaShonda found him in bed texting and sending Facebook messages from their Layton, Utah, home.

The 45-year-old veteran and self-described gym rat had experienced severe neurological side effects from an anthrax vaccine in the U.S. Air Force in 2003 and had procrastinated about getting the COVID-19 vaccine. He’d finally booked the first shot for mid-June 2021, only to be beset by chills, coughing, and clogged lungs on June 5.

After a week of bed rest, Manny seemed to be better. That he was online chatting with friends was encouraging, LaShonda thought. “You look better,” she said. “Go outside and get some fresh air.” He stood up and started coughing.

Days before Manny Arocha fell ill with COVID-19, he and his wife LaShonda worked out at their local gym.

Days before Manny Arocha fell ill with COVID-19, he and his wife LaShonda worked out at their local gym.

UNABLE TO CATCH HIS BREATH, HIS CHEST AND HEAD HURTING, DIZZINESS OVERCAME HIM—AND WITH IT A FEELING OF DREAD.

LaShonda took him to a local hospital. Normal blood oxygen levels are 95 percent to 100 percent.

“This can’t be real,” LaShonda thought. Just a year before, she and her older sister, Nakia Hall, had made the most difficult decision of their lives in a Kentucky ICU, withdrawing life support from their father.

The sisters, both veterans and from a military family, had been close all their lives, although they had differences in personality and beliefs. Nakia and her husband Carl were devout Christians, while Manny and LaShonda felt living for each other and their three boys was enough.

But shortly after their father’s death, the sisters had a falling out. Nakia tried to reconnect but LaShonda blocked her on her phone and deleted her on social media. After LaShonda dreamed that their father, while repairing a door, told her to fix her relationship with Nakia, they started talking again, but it wasn’t the same.

In the wake of Manny’s hospitalization, LaShonda needed prayers—and she needed them constantly.

Nakia had a group of people she regarded as dedicated to prayer. She offered their support for Manny. Nakia expected Manny to say no, but he agreed. For the first two weeks, while he was still conscious, Nakia, her husband Carl, and other members of her group prayed daily with him over the phone’s speaker.

INITIALLY, LASHONDA AND NAKIA CONVINCED THEMSELVES THEY WEREN’T WORRIED. ALPHA-MALE MANNY WAS ALWAYS STRONG, CALM, AND NEVER SHOWED WEAKNESS.

Manny and LaShonda met in the U.S. Air Force. He inspected planes across the globe, while she worked in administration.

Manny and LaShonda met in the U.S. Air Force. He inspected planes across the globe, while she worked in administration.

But as the days rolled on, it took more and more oxygen to improve Manny’s blood oxygen rate, until there was so much air in his body it became trapped under his skin and crackled to the touch.

THEN THE PANIC ATTACKS STARTED.

When nurses had Manny lie on his stomach—allowing oxygen to get to the otherwise hard-to-reach back of his lungs—he turned over but was then unable to catch his breath. He jumped up, ready to flee, then slumped down, feeling as if he was drowning on dry land.

He’d wake up at night, disoriented, and tear off the BiPAP mask feeding him oxygen, struggling with nurses trying to stop him. Mittens were tied to his hands, his wrists secured to the bed’s railings. Just like her father, LaShonda thought.

Disoriented and frightened, Manny had to be restrained to his hospital bed, his hands in mittens to stop him struggling with nurses.

Disoriented and frightened, Manny had to be restrained to his hospital bed, his hands in mittens to stop him struggling with nurses.

Manny was beyond exhausted. Hospital staff told him “keep breathing,” but it was so tempting to give up and die. At the very moment he concluded, “I’m done, I can’t keep going like this,” the old Manny—the man who never backed down from a challenge—stepped up. “I'm gonna keep going and going,” he told himself.

Nakia forbade LaShonda from crying. “Don’t you go into the ICU crying. Let him see you whole and know he’s coming home.” LaShonda did as she was told—until June 23. That was the day she found Manny curled up in a fetal position in an upright chair and, in tears, knew with crystal clarity he would be sedated and put on a ventilator.

The limits of the sisters’ revived relationship only went so far. When Nakia asked LaShonda if she wanted her by her side, she never replied. The Hall family had plans that summer, and Nakia struggled with the thought of seeing Manny sick in the hospital, 12 months after her father’s death. But when an exhausted LaShonda texted her, “I’ve prayed and called out to God,” a concerned Nakia sought Carl’s counsel. He didn’t think twice. “You need to go.” So, on July 3, Nakia and her daughter Briana flew to Utah.

VERY FEW PATIENTS HAD BEEN AS SEVERELY ILL WITH COVID-19 AS MANNY WAS.

One option offered a lifeline: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO). It functioned as an external lung, withdrawing his blood through a garden hose-thick tube in his neck, circulating it through an oxygenator and pumping it back into a large vein, the vena cava, which carries blood back into the heart from other parts of the body. While the hospital where he was being treated didn’t provide ECMO, University of Utah Hospital did.

Manny met University Hospital's stringent criteria for employing the staffing-heavy resource of ECMO. He had single organ dysfunction (in his lungs) and was otherwise healthy and fit. The hospital agreed to take him. But when LaShonda arrived at the local hospital’s ICU on his transfer day, ICU staff met her with blank faces.

“They don’t know when he’s leaving,” she told Nakia in a panic. LaShonda asked her to pray, put the phone on speaker, and sat by Manny’s bedside.

“I NEED A MIRACLE,” LASHONDA SHOUTED, HER VOICE BREAKING IN DESPAIR.

Seconds later, a lanky man with spiky hair wearing the black flight suit of AirMed, U of U Health’s air ambulance service, kicked his leg forward around the corner, executed a right turn, and marched into the unit. He was followed by a team including mechanical circulatory support nurse and clinical nurse coordinator Kathleen Stoddard, from U of U Health's Cardiovascular ICU; cardiac surgeon and ECMO specialist Hiroshi Kagawa, MD; a respiratory therapist; and a flight paramedic.

“They’re here!” LaShonda screamed. “They’re here.”

Manny was too sick to transfer with only a ventilator. Stoddard felt that if he didn’t go on ECMO that day, he wouldn’t be alive the next morning. His kidneys were beginning to shut down. The lack of oxygen to his organs meant they were dying little by little. With help from the local hospital staff, Kagawa put him on ECMO at his bedside.

THE OPERATION DID NOT GO SMOOTHLY. THE AIR SACS IN MANNY’S LUNGS HAD BECOME SO WET AND FLUFFY FROM COVID-19 THAT THEY COULDN'T FUNCTION, AN ALL-TOO-FREQUENT AND DEVASTATING COMPLICATION OF THE VIRUS' IMPACT ON INFECTED PATIENTS.

Diuretics were administered to try to dry them out. Manny’s symptoms were so severe that the volume of diuretics used to dry out his lungs had left him dehydrated. When they started the ECMO machine, it suctioned tissue into the cannula holes rather than his blood, which was too thick to flow.

It was akin to trying to suck a milk shake up through a straw, but the shake was so thick the straw collapsed.

To combat “suck-down,” which comes with a risk of tearing a hole in the large vein, the team gave him several liters of fluid. Minute after agonizing minute, they worked feverishly to get his blood flowing through the cannula. The longer it took, the greater the risk of a blood clot developing and clogging up the oxygenator. Finally, after five minutes, Manny's blood flowed through the cannula to the oxygenator, his blood oxygen climbing rapidly from 80 percent to 100 percent.

When they landed at University Hospital, Kagawa repositioned the cannula in the operating room. Two days later, because Manny was such a strong, large man, they had to add a second cannula in his groin.

Cardiothoracic surgery fellow Nicolas Contreras, MD, was raised in a spiritual household, and as a member of Manny’s care team, he found a commonality with LaShonda and Nakia.

THEIR SPIRITUALITY AND THE WAY THEY CARED AND PRAYED FOR NOT ONLY MANNY BUT HIS HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS WERE THE KIND OF INTANGIBLE ELEMENTS HE BELIEVED MADE A DIFFERENCE IN THE MEDICAL JOURNEY OF HIS PATIENTS.

He and the team at the Cardiovascular ICU (CVICU), who treated Manny Arocha, did all that science asked of them. But in the healing process, there are things that sometimes science can’t quantify.

Medicine, Contreras argued, has the potential to be more than simply mechanical support and new technology. If that is the sole focus, then providers, he said, “are missing a critical element of the human being who is our patient and the mystery of human healing.”

It wasn’t only science and providers that fought for Manny’s life. It was Manny and his determination to return to his loved ones. And it was his family. How they constantly advocated for him by his bedside. How they drew on their faith and the hope it gave them.

“We have an army to help take care of your loved one,” said John Skaggs, MD, an anesthesiologist and critical care specialist at U of U Health who helped oversee Manny’s treatment: “Nurses, respiratory therapists, ancillary staff, doctors.”

“AT SOME POINT, THE ARMY DISSIPATES TO WHAT YOU HOPE IS THE ARMY OF THE FAMILY,” SKAGGS CONTINUED. “REMARKABLY, HE HAD THAT KIND OF FAMILY UNIT.”

Manny was moved into room 3032 of the CVICU on the second floor of University Hospital. The eight-year-old unit, much like the Medical ICU, has a reputation for caring for the sickest of the sick. Their mixture of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and heart and lung transplant patients benefit from cutting-edge medical technology that can keep death at bay—and many times see patients fully recover.

LaShonda couldn’t go into Manny’s ICU room because she wasn’t fully vaccinated, although by then she and her two older boys, Manny Jr. and Izzy, had had the first shot. She stood outside Manny’s room, shocked by the water-hose thickness of the blood-filled cannulas in his neck.

Clinical nurse coordinator Stoddard—whom the family would come to call with much fondness “Miss Kathleen"—saw LaShonda's concern and hugged her. “He’s going to be OK,” she told her. Afterwards, Stoddard thought, “Oh man, I sure hope I’m not wrong.”

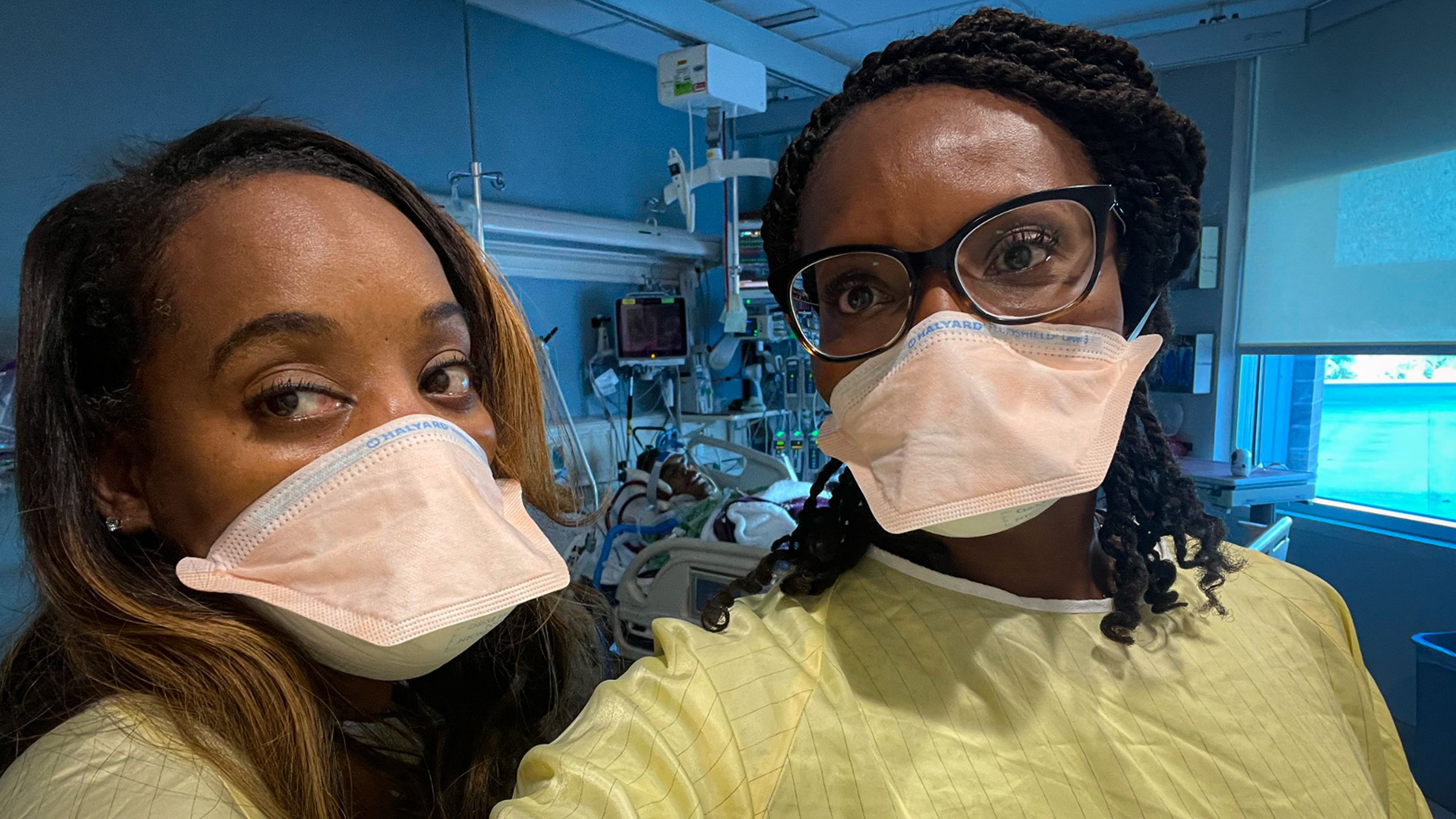

FULLY VACCINATED NAKIA, IN GOWN AND MASK, WAS LASHONDA’S EYES AND EARS IN MANNY’S ROOM, WHILE HER SISTER SAT IN THE WAITING ROOM, FACETIMING WITH HER.

Nakia tried to bring up how much it meant to her that they were close again. In those first days, LaShonda wasn’t interested. All she wanted was her prayers.

Nakia had her own demons to battle. This was the fourth time she prayed at the bedside of someone fighting for their life. She told a prayer partner, “Every time I go into the ICU and I lay my hands on a person, they always die.” Despite the doubts that assailed her, she took her place by Manny’s CVICU bed and prayed.

Manny had been intubated long enough that his care team had concerns the ventilator-attached tube down his throat would damage his vocal cords. They decided to extubate him, surgically insert a tracheostomy tube (trach) in his neck below his cords, and attach the ventilator there.

ON THURSDAY JULY 7, SURGICAL STAFF INSERTED AN 8.0 TRACH IN MANNY’S NECK. BUT IN THE HOURS AFTER THE SURGERY, THE WOUND WOULD NOT STOP BLEEDING.

Patients on devices like ECMO are on blood thinners to ensure there aren’t blood clots. That had been briefly discontinued for the trach operation, but even so, Manny's bleeding wouldn’t stop. Working alone, nurse Brittnee Zacherson fought to staunch his bleeding, applying pressure and endlessly changing dressings as blood ran not only from the trach site but also from his mouth. She couldn’t even turn to the computer at the bedside or address the monitors and the drips. The moment she turned away, Manny was gurgling in his own blood.

A horrified Nakia could see the worry on Zacherson’s face. She stood by the window and quietly read out a psalm from the Bible about God’s protection and strength. Like Nakia, Zacherson was a person of faith and prayer. She would pray in her car instead of listening to the radio, talking to God about the difficulties in her life. As much as she was concerned that noise might spike his blood pressure and lead to more bleeding, she admired what Nakia was doing, helping her brother-in-law in the best way she knew how.

EVENTUALLY, THE BLEEDING STOPPED. ZACHERSON MOVED ON TO OTHER PATIENTS. WHEN SHE HAD A MOMENT TO LOOK IN ON MANNY, SHE WAS MOVED TO SEE HIS SISTER-IN-LAW STILL THERE, HEAD BOWED IN PRAYER.

Nakia Hall and Brittnee Zacherson

Nakia Hall and Brittnee Zacherson

Nakia and LaShonda left the hospital earlier than usual that day. What Nakia had seen in Manny’s room was hard to take in—even with her 18 years as an army medical service corps officer—and she wanted some respite. They drove to Target, and as they pushed a cart around the aisles they spotted a couple they knew from Elevation Church, a Layton-based Christian church the sisters had attended for the first time at Nakia’s suggestion four days before.

“Please keep my sister and her husband Manuel in your prayers,” Nakia said to Kelly, the church’s new worship pastor, and his wife Cheri. “He’s on life support from COVID at University of Utah Hospital.”

“Let’s pray for him right now,” Cheri said. The sisters noticed a vertical scar in the base of her neck, which Cheri later confirmed was from a childhood tracheotomy.

LaShonda felt awkward. Other shoppers were there to get in and out, and here they were blocking the aisle.

THEY HELD HANDS IN A CIRCLE AND PRAYED, SHOPPERS EDGING THEIR WAY AROUND THEM, OR ELSE GOING BACK THE WAY THEY HAD COME.

Nakia told her sister that the Target encounter was God’s way of urging them to remain faithful. “Even though it's scary right now, what he did for Cheri, he's going to do the same thing for our family,” she told LaShonda.

Several days later, Contreras told the sisters in a hallway next to the CVICU that, since Manny’s bleeding was under control, they would replace the 8.0 trach with a 6.0 one. “Can we pray for you before the operation?” Nakia asked. He agreed. She put a hand on Contreras’ shoulder, told LaShonda to do the same, and then said a prayer.

As much as LaShonda wasn’t looking to rekindle lost ties, Nakia’s persistent, loving, at times motherly ways wore her down. “It's hard to be mad at somebody that's helping you navigate through life,” she thought.

Despite the thawing between the sisters, they still fought. When LaShonda misinterpreted Manny’s online chart, believing he had brain damage, she wailed in despair in the car as Nakia drove them to the hospital. Nakia slapped the steering wheel, screaming at her, “Let me have faith.”

“Why can't I cry?,” LaShonda shouted back in tears. “It’s a sad cry.”

“You're mourning, you're not crying,” Nakia told LaShonda. “And he's not dead.”

As the weeks passed, nurses watched Manny’s muscles atrophy. They compared him to the many photos on the walls that the family had put up and saw how much of him had been erased by the disease.

Over the six weeks Manny was unconscious, he lived a life unknown to anyone around him. And it wasn’t a good one. It was full of haunting imagery of violence, temptation, and horror.

The nurses came to appreciate the family’s dedication to Manny. They’d hear alarms go off in his room, run to his door, and then, rather than having to gown up and go in, they’d look at Nakia—or, later, LaShonda after she was fully vaccinated—and get a thumbs-up from sisters who had learned from hard-won experience what was and wasn’t an emergency that needed immediate medical attention.

LaShonda (left) and Nakia standing guard over Manny in his CVICU room. Together or separately, they always advocated for him with passion and empathy for his providers.

LaShonda (left) and Nakia standing guard over Manny in his CVICU room. Together or separately, they always advocated for him with passion and empathy for his providers.

The sisters did their best to keep life normal for their families during this process. They went out for meals; the adults went on hikes or curled up with the kids to watch a movie on TV.

Heading out to Elevation Church, the family “army” that supported Manuel Arocha... (back row left to right, Kiana Hall, Izzy, Manny Jr. and Carl Hall; middle row, the sister's mother, Debra Hubbard, LaShonda, Yasi and Briana Hall; front row, Nakia and Carl Hall Jr.)

Heading out to Elevation Church, the family “army” that supported Manuel Arocha... (back row left to right, Kiana Hall, Izzy, Manny Jr. and Carl Hall; middle row, the sister's mother, Debra Hubbard, LaShonda, Yasi and Briana Hall; front row, Nakia and Carl Hall Jr.)

... still found time for levity.

... still found time for levity.

But LaShonda and Manny’s boys struggled with not seeing their father and worried about their mother. One evening, while bathing her youngest, Yasi, LaShonda cried over the uncertainty they faced—over how much she missed her husband.

“What’s wrong, Mama?” he asked.

“I miss Dad.”

“He’s coming back home,” he told her.

She agreed without thinking.

“Why are you crying then?” he asked.

Good question, she thought.

BY MID-JULY, DOCTORS WERE TRYING TO GET MANNY TO BREATHE ON HIS OWN, TAPERING OFF THE ALTERNATE-LUNG ROLE ECMO PLAYED. BUT HE WAS NOT RESPONDING TO NEUROLOGICAL CHECKS, AND HIS VITALS CONTINUED TO FLUCTUATE.

While Manny's eyes were sometimes open, he wasn't awake.

While Manny's eyes were sometimes open, he wasn't awake.

As July came to an end, the door to Manny’s ICU room had remained closed since his arrival in order to contain any accidental exposures of the virus to staff and the hospital.

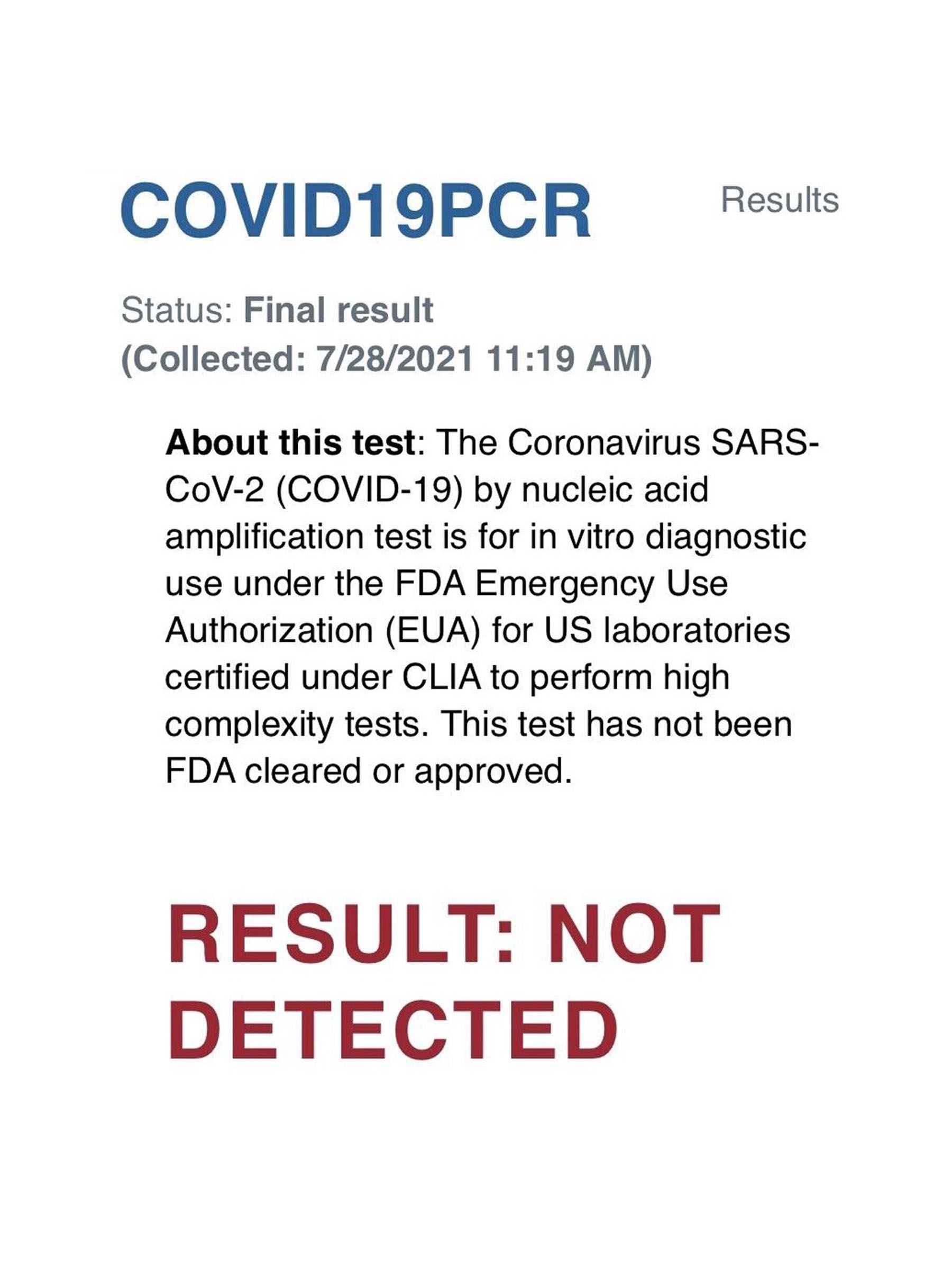

BUT THEN, ON JULY 29, THE DAY BEFORE NAKIA WAS DUE TO RETURN TO TEXAS, MANNY’S COVID-19 TEST CAME BACK NEGATIVE. HE WAS FREE OF THE VIRUS.

Nakia wrote in her journal of Manny’s illness, “When Shonda and I walked back into the ICU room, Manuel’s door was WIDE open. I was SHOCKED!” The sisters put on worship music, LaShonda rejoicing and praying over Manny at what they were sure was the beginning of his journey of recovery.

AT LAST, THEY HAD SOMETHING TO CELEBRATE.

The sisters went to a Thai restaurant, and over drunken noodles, egg rolls, and Thai fried rice, they allowed themselves to be happy after so many weeks of tears, worrying, and prayer. Afterwards, they drove up to the Utah State Capitol, which they passed twice a day to and from the hospital, ran a victory lap around its imposing walls, and took turns photographing each other celebrating on its steps.

The CVICU medical team wanted to start waking Manny up from his lengthy sedation. For days, then weeks, Manny didn't respond, despite his sedation having been stopped. When he finally did start to wake up, for a brief while he couldn't move his legs. Multiple CAT scans of his brain revealed nothing amiss.

And then, slowly, painfully, he began to crawl out of his long, chemically-imposed isolation. One nurse told LaShonda and Nakia it was “like being tossed in the sea,” rocking backwards and forwards and not knowing where you are.

MANNY'S RELIEF HIS TIME ON EARTH WASN’T OVER YET WAS BEYOND ANYTHING HE COULD PUT INTO WORDS.

Even if, in some ways, he still expected to go back to the netherworld he had lived in his mind for so long.

For LaShonda, Nakia, and Manny’s nurses and providers, the first signs that he was able to communicate with them were almost overwhelming.

Manny moved his eyebrows to music LaShonda played on her phone for him. A physician assistant told the sisters, “It’s like someone turned the switch back on.”

As Manny slowly emerged from the medical ether, he found himself connected to so many tubes, unable to eat or speak. His body felt numb, broken from the top of his head to the soles of his feet. “Just imagine every physical ailment you've ever had all at the same time,” he later told LaShonda.

THE CACOPHONY OF MEDICAL MACHINERY WAS UPSETTINGLY LOUD. “WOW, THIS IS WHAT’S KEEPING ME ALIVE?” HE THOUGHT.

Surrounded by cutting-edge medical technology, the ECMO oxygenation device stands next to Manny on the left.

Surrounded by cutting-edge medical technology, the ECMO oxygenation device stands next to Manny on the left.

Staff struggled with stopping occasional bleeds.

Staff struggled with stopping occasional bleeds.

He had no control over his body or its functions. He couldn’t stand up, walk, or go to the toilet. He knew in his mind what he wanted to do, but even writing on a board, “My name is…” eluded him. When the physical therapist came in to work on his movement, bending his leg, he felt like it was going to fall off.

Therapists moved his limbs, giving him minimalist exercises to start. They also put him on a tilt table, which prepares patients for standing without having to support themselves, something which at first they are often too weak to do.

Physical therapists in CVICU worked on getting Manny to stand up. As much as it hurt him, as much as he struggled with so little strength in his atrophied muscles, with each day LaShonda saw improvements.

The sisters’ mother, Debra Hubbard, who had come from Texas to support her children and son-in-law, took over from Nakia accompanying LaShonda to the hospital. Nakia wrote in her journal, “Shonda and Momma teamed up, not allowing fear to grip their hearts.” Quoting from Proverbs, she then wrote, “She is clothed with strength and dignity; she can laugh at the days to come.”

The sisters' mother, Debra Hubbard, took over from Nakia, supporting LaShonda and spending time with her son-in-law at the CVICU.

The sisters' mother, Debra Hubbard, took over from Nakia, supporting LaShonda and spending time with her son-in-law at the CVICU.

Thoughts of one day returning to the outside world made Manny anxious. He had awoken to a still-raging pandemic. One relative, a little older than him, had been in a small rural hospital for two weeks with COVID-19 before dying on a ventilator.

The specter of death was never far from him. When a CVICU patient coded—had a heart attack—he’d hear running feet to another room and wonder, “When’s it going to be me? Am I going to be next?”

Anxiety would strike and he would break down and weep. At times he wanted to give up, to not go on, but LaShonda reminded him he was fighting for them. “We’ve gone too far to let it go,” she told him.

He’d mouth again and again to LaShonda that he wanted his restraints removed. When she finally understood and told him it wasn’t possible right now, he closed his eyes as if to shut her out.

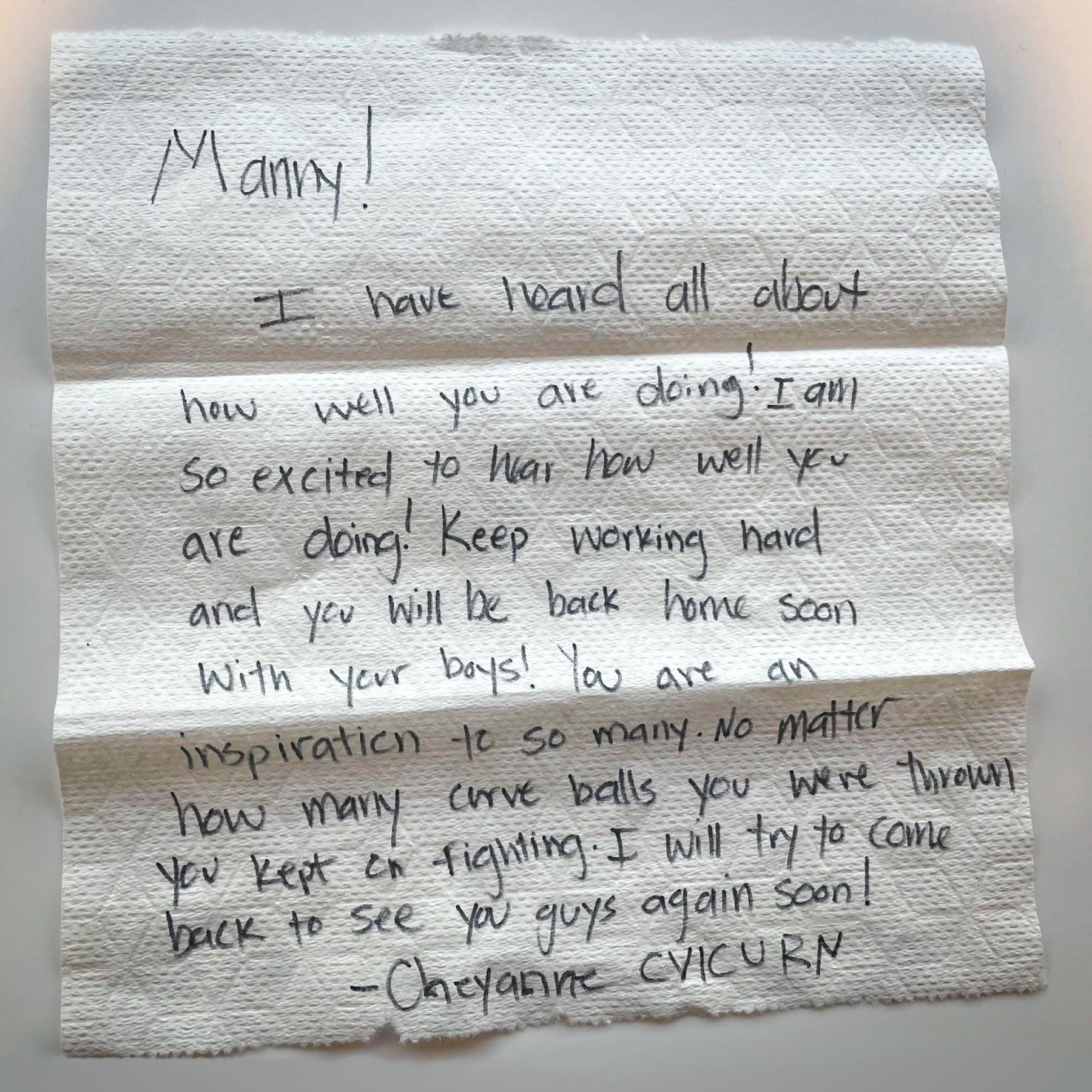

Nurse Cheyanne Mulcock had worked in the CVICU two years when she cared for Manny for six straight shifts. She stayed up with him multiple nights, telling him, “You’ll be fine, just breathe,” as he battled anxiety. She’d try to figure out what he was mouthing to her, until she realized it was that he wanted to go home to see his sons.

Manny wiggled his toes a little, moved his hands, opened his eyes a little more, and responded to people. Gradually, the old Manny—or at least one burnished in the fires of the virus—emerged. He felt like he was a snowball rolling down a mountain.

EVERY DAY, HE HIT A NEW MILESTONE—AND IT JUST KEPT GOING AND GOING AND GOING.

A speech therapist helped him attach a voice box so he could utter his first words since mid-June. As much as Manny, still restrained to the bed and without control of his hands, didn’t like the device, he forced himself to speak. “Where's my wife?” was the first thing he said.

The last shift Mulcock had with him, Manny was FaceTiming a friend about how much he wanted to get back to his post-Air Force career of coaching high school football. “Okay,” she thought. “He’s thinking of the future now. We’re doing a bit better.”

MANNY’S BREATHING HAD IMPROVED SO MUCH, STAFF FELT IT WAS TIME FOR HIM TO COME OFF ECMO AND LET HIS LUNGS AND HEART WORK ON THEIR OWN, ALBEIT WITH THE VENTILATOR ATTACHED THROUGH THE 6.0 TRACH.

On August 11, the cannula in his groin was removed. Two days later, the cannulas going in and out of his neck were also taken out.

IT WAS HIS 62ND DAY IN THE HOSPITAL.

That same night, his breathing deteriorated due to a pneumonia infection, and he had to undergo an emergency re-installation of ECMO, this time with cannulas in his upper thighs. It meant the planned reunion between Manny and his sons, who had not seen him for almost two months, had to be postponed. The sisters and their mother wept in disappointment.

A few days before, Manny’s parents, Roberto and Gregoria Arocha, had also come to visit him from Michigan. Until then, they had texted videos with supportive messages.

Like the sisters, they drew on their faith to support their son. They’d asked a Catholic priest to come to his CVICU room and bless a statue of St. Martin de Porres. Gregoria took the statue and moved it all over Manny's lungs, trying to banish the disease from his body.

Manny's mother, Gregoria Arocha, arrived from Michigan with her husband to visit her son and pray for his recovery.

Manny's mother, Gregoria Arocha, arrived from Michigan with her husband to visit her son and pray for his recovery.

SIX DAYS LATER, MANNY CAME OFF ECMO FOR GOOD. HE’D BEEN ON IT FOR 48 DAYS. ONLY ONE OTHER PATIENT HAD BEEN ON LONGER—AT 57 DAYS.

If there was a moment when Manny's anxiety receded, it was when rehab doctor Chris Duncan, MD, told him he was being transferred to Craig H. Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital next door. “You’re going to be OK—I think you’re over the hump,” Duncan told him. Almost in tandem, Manny and LaShonda exhaled the same “we’re free” sigh.

Prior to going to Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital, Manny was briefly moved to the Medical ICU in order to free up bed space in the CVICU. Medical ICU physical therapists also worked to improve his ability to stand.

When physical therapist Shannon Wells met Manny on his first day at Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital, she found him tired, anxious, and having a hard time breathing. She wanted him to listen to his body and respect its limitations. Given the severity of his COVID-19, she expected him to only walk 10 to 15 feet on their first encounter.

Despite her 10 years in physical therapy, Wells had been stunned by how COVID-19 left recovering patients profoundly impaired. Not only did they have functional weakness while struggling with endurance, fatigue, and breathing, there were also debilitating anxiety spirals. But Manny amazed her as he walked, in slow stages, 160 feet.

EVEN THOUGH HE WAS TIRED, HIS BODY HURT, AND HE JUST WANTED TO STOP, HE VOLUNTEERED FOR WEEKEND THERAPY, ANYTHING TO KEEP IMPROVING. HE JUST WANTED TO GO HOME.

Physical therapist Shannon Wells pushed Manny as hard as she could through his rehab at Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital.

Physical therapist Shannon Wells pushed Manny as hard as she could through his rehab at Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital.

Manny worked with therapists on his hand-eye coordination while re-learning daily activities.

Manny worked with therapists on his hand-eye coordination while re-learning daily activities.

Sporting a new haircut courtesy of his best friend Kenny, Manny works on more eye-to-hand coordination improvement tools.

Sporting a new haircut courtesy of his best friend Kenny, Manny works on more eye-to-hand coordination improvement tools.

Wells admired how connected LaShonda and Manny were, particularly in the way they showed through their love for their children the strength of their family.

Manny’s hard work bore fruit. His progress with daily living needs—re-learning basic day-to-day activities, from opening a can of soda to going to the bathroom on his own—and his speech and physical therapy meant his release date was moved up a little earlier than the four weeks initially tabled.

Staff from CVICU came to Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital to see how he was getting on. Hiroshi Kagawa, who led the ECMO surgery team treating Manny, marveled at how healthy Manny looked compared to when he was first admitted to University Hospital.

Hiroshi Kagawa, MD, visited Manny (pre-Kenny haircut) at Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital. Behind them are pictures the family put up in every room that Manny was hospitalized in. Nurses commented on how much the collages of his life helped them understand who he was and where he came from.

Hiroshi Kagawa, MD, visited Manny (pre-Kenny haircut) at Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital. Behind them are pictures the family put up in every room that Manny was hospitalized in. Nurses commented on how much the collages of his life helped them understand who he was and where he came from.

CVICU clinical nurse coordinator Stoddard also visited Manny in rehab. It often took nurses a moment to recognize a former patient, and the first thing she was struck by was his huge smile of surprise when she arrived unannounced at the door to his room. She hugged him as he told her about how much rehabilitation he was doing all day, every day. What amazed her after weeks of Manny being unable to speak in her unit was that he was actually talking. “Your voice is so strong,” she said. It was almost as if, she thought, he hadn't been sick.

Not everyone from CVICU who went to see him in rehab managed to catch him. Nurse Mulcock left him a note.

TWELVE DAYS BEFORE HE WAS SET TO BE RELEASED, MANNY WHEELED HIMSELF OUT IN FRONT OF NEILSEN REHABILITATION HOSPITAL AND AWAITED THE ARRIVAL OF HIS CHILDREN.

Six-year-old Yasi had been told not to run and jump on him as he usually did but was nevertheless the first to reach his father, who beckoned at him greedily for a hug. After Yasi, it was Izzy's turn.

Manny's middle son, Izzy, collapsed into his arms.

Manny's middle son, Izzy, collapsed into his arms.

The first time seeing their father in person after 60 days spent battling COVID-19. Izzy and Manny Jr. (standing) while Yasi sits in his father's lap outside Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital.

The first time seeing their father in person after 60 days spent battling COVID-19. Izzy and Manny Jr. (standing) while Yasi sits in his father's lap outside Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital.

He held each of his children for the first time since the beginning of June. In so many ways, he wasn’t the same person he had been before he got sick. He had lost 46 pounds. He was covered in scars and needed oxygen with him at all times.

As much as he didn’t want his sons to see him so weakened, he couldn’t contain his excitement as each of them held him tightly. His middle son Izzy broke down and whispered through tears into his father’s shoulder, “I thought you were going to die.”

If Manny got out of the hospital alive, Nakia had sworn she’d be there to witness it. So on September 15, she flew to Utah, a day before his scheduled release, and joined Manny and LaShonda when they went in the afternoon to the CVICU to say thank you. They expected only a few people to say hello but instead were swamped.

MANNY STOOD UP FROM HIS WHEELCHAIR, FOR THE FIRST TIME MEETING THE STAFF AT EYE LEVEL. “I WANT TO THANK YOU FOR SAVING MY LIFE,” HE SAID.

Nurses and providers told him it was they who were grateful. “We all need something like this,” one said. Another piped in, “We’re so glad you came back. We don’t always get to see the people that survive.” They thanked him for being strong enough to keep going, for working so hard to get better.

Nakia, LaShonda (front row left), and Manny (center in a grey sweatsuit) surrounded by CVICU staff, with Nurse Stoddard on Manny's left.

Nakia, LaShonda (front row left), and Manny (center in a grey sweatsuit) surrounded by CVICU staff, with Nurse Stoddard on Manny's left.

Manny looked around for Nurse Mulcock, who had helped him through many anxious nights. A nurse had emailed Mulcock that Manny, his wife, and sister-in-law were coming, and she drove from a funeral to hug him, joking, “I got all dressed up for you.”

Manny with Nurse Cheyanne Mulcock.

Manny with Nurse Cheyanne Mulcock.

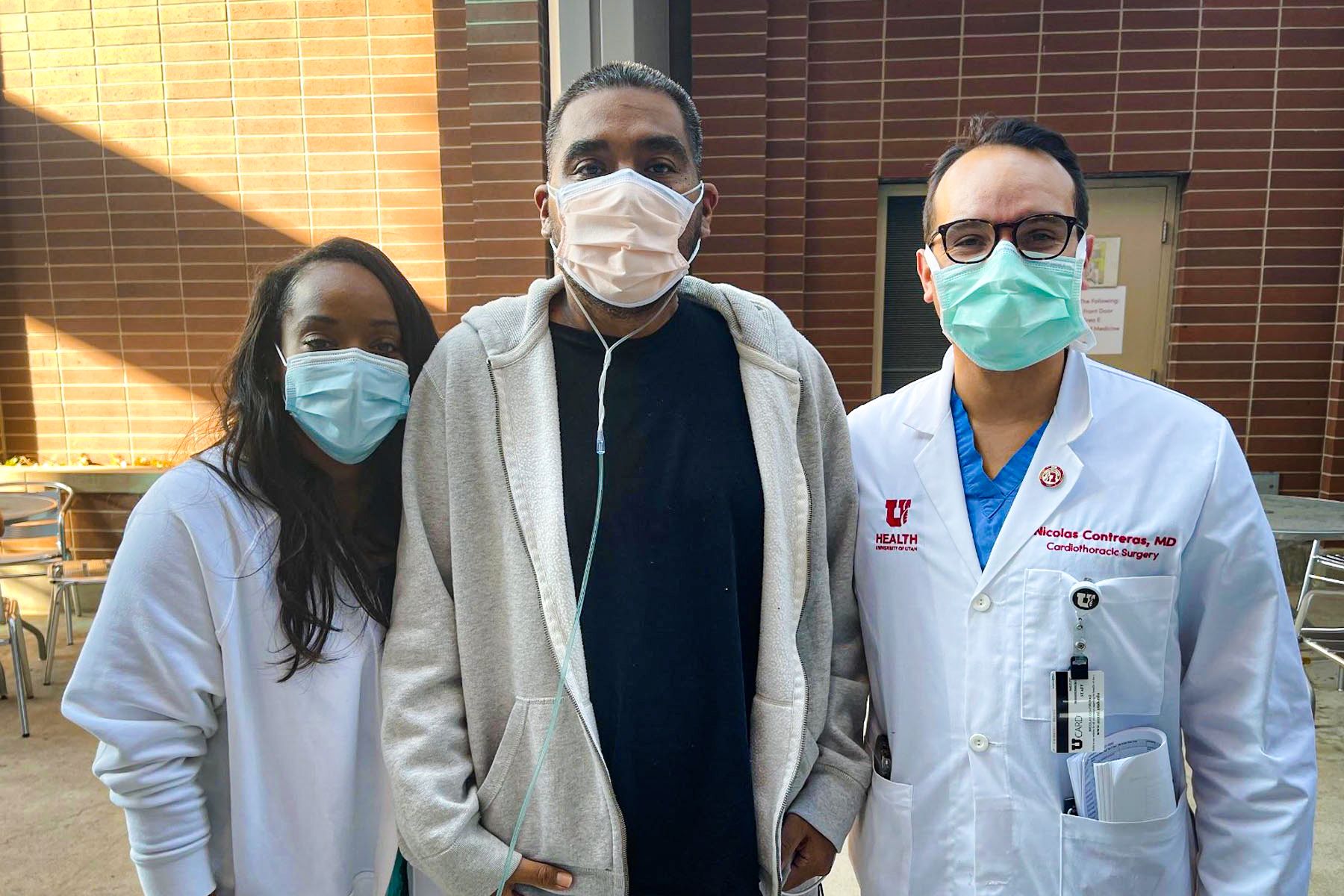

When Nicolas Contreras saw LaShonda, Nakia, and Manny in the line at the cafeteria, emotion welled up inside him at how each time he’d helped in Manny’s care—assisting operations, removing ECMO cannulas—he had helped one of the unit’s sickest patients get back on his feet. “I’ve been praying for you ever since,” he told Manny.

LaShonda and Manny with Nicolas Contreras, MD, the last day of Manny's hospitalization.

LaShonda and Manny with Nicolas Contreras, MD, the last day of Manny's hospitalization.

Manny wasn’t the only one who wanted to express gratitude for his recovery. LaShonda and Nakia had thanks to convey, in their own way. In the Bible, King David danced in praise of God’s presence in his life. They went out in front of the Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital lobby to do their own dance of praise. As doctors, nurses, and patients watched through the window, they energetically danced their gratitude to God that Manny was going home.

And that wasn’t the only gift the last months had bestowed on them. When LaShonda drove her sister to the airport for her flight home to Texas, she hugged her and stepped back. “You know, you’d get on my nerves so bad when you would say you’re so glad we’re getting a second chance.”

LaShonda smiled. “In the end, I was so glad I had you by my side.”

As LaShonda drove her husband home, Manny struggled with his fears. If anything wasn’t right, he’d always been able to rely on the nurses to fix it. He didn’t have that anymore, and it scared him.

In the days after he got home, Manny looked back on his COVID-19 months and tried to understand what he’d lost and gained—and who he’d become. The virus had taken months of his life and his health and suspended his barely begun dream of coaching high school football.

Even his sense of reality had not been left unscathed. Sometimes he half-expected to wake up not to his newly restored family life but the nightmares that had supplanted it while he was unconscious. It was almost like those nightmares were his real life.

In its way, the virus gave him things, too. It made him value and experience his children even more deeply than he had. When he was driving one day with Manny Jr., the teen told him how he would have felt alone if he had died. Why, Manny asked him? “I've always had you,” his son replied. “We have a really close relationship.”

COVID-19 GAVE HIM A DEEPER FAITH IN THOSE HE LOVED.

One day his wife asked him why he never asked her—as he had always done—“Do you love me?” Since he had been back, he hadn’t asked that question and it rankled. “Why don’t you ever ask me anymore?”

He looked at her. “You showed me. There isn’t anything I have to ask. You showed it to me. And that’s that.”

After 96 days battling the virus and its impact on his lungs and body, finally the Arochas were going home.

After 96 days battling the virus and its impact on his lungs and body, finally the Arochas were going home.

Story by Stephen Dark

Design by Jessica Cagle

Family images provided by

LaShonda Arocha and Nakia Hall