In just 10 years, the University of Utah School of Dentistry transformed oral health care for the underserved in Utah.

By Stephen Dark

January 10, 2025

When Yukiko Stephan filed into the front rows of Kingsbury Hall along with 49 other fourth-year graduates in May 2024, her thoughts were of a woman sobbing in her office eight years before.

As the University of Utah School of Dentistry’s (SOD) graduates waited for Dean Wyatt “Rory” Hume, DDS, PhD, to begin the proceedings, the 36-year-old dental graduate recalled how different access to oral health care had been in 2016. In the midst of a recession, the Utah legislature decided in the mid-2000s to cut Medicaid dental benefits to eligible adults in the state. That all but eliminated oral health care for 220,000 people, leaving them only eligible for emergency extractions.

The middle-aged woman had fled West Africa as a refugee and recently settled in Utah. When she met Stephan in 2016, she had been in extreme pain from abscessed front teeth and chronic gum disease. Despite speaking little English, she’d managed to navigate the system to find a provider.

With no interpreter provided, she had some teeth extracted, not understanding that her Medicaid would not cover replacing the missing teeth. A week later, in Stephan’s Salt Lake City office of the refugee nonprofit, International Rescue Committee (IRC), where she worked as a health promotion coordinator, the woman was inconsolable. Her smile was gone. She felt disfigured by the extraction. How would she ever find work to start a new life?

That woman’s plight—and hundreds of refugees and asylum-seekers like her—convinced Stephan to begin dental training.

Sitting in Kingsbury Hall in 2024, Stephan recognized that so much had changed since that 2016 conversation. She now had the tools and knowledge to treat refugees' oral health needs herself. Not only had she studied for four grueling years to become a dentist, she’d also helped pioneer an initiative providing monthly classes on oral health for newly arrived IRC clients. The classes were about what to expect at dental appointments and concluded with dental screenings. Through a grant, the dental school also helped refugees secure comprehensive dental care. At the same time, Utah’s state legislature had restored full dental coverage for many Utah Medicaid patients.

Yukiko Stephan and family.

Yukiko Stephan and family.

Stephan glanced down the cap-and-gowned row at her graduating classmates, some ready for private practice and others, like herself, passionate to treat society’s most vulnerable. Looking up at the faculty on stage, she was struck by how uniquely positioned the School of Dentistry was to address that need.

A MOTHER'S DETERMINATION

Unlike most newer U.S. dental schools—mostly for-profit and stand-alone—Utah's school is the first started in the last 30 years connected with a research institution. From the primary funder’s mandate to serve those without access to dental care, through partnerships with the Utah legislature and Utah Medicaid, community-run nonprofits, and Utah’s dentists, the SOD strives to eliminate barriers so Utah’s underserved can receive oral health care.

Since opening in 2015, threaded through the School of Dentistry’s short history has been a commitment to serve that has pushed it onto the national stage.

Such an evolution would not have succeeded without buy-in from the school’s leadership. That buy-in starts with Hume. He grew up on farmland in Southern Australia, where most children had dental decay and by age 20 had had their teeth extracted as the cheapest way to avoid a future otherwise dominated by pain, illness, and expense. Hume’s mother, he says, “was determined her children would have teeth, not dentures.” His family spent far more money on dental care than any other aspect of health—not that they had much money to begin with.

Second-year students working in the SOD's simulation lab.

Second-year students working in the SOD's simulation lab.

Hume’s state scholarship to study dentistry was dependent on him returning to the countryside to provide oral health care. While he was at university, decay prevention changed. It began with the introduction “of fluoride, fissure seals, and a full understanding of the relationship between dietary choices, behaviors, and the initiation and progression of tooth decay,” he recalls. The results were astounding. In 1970, the average South Australian child had 12 decayed, filled, or missing teeth by the time they were 12 years old. By 1985, the average was 0.5.

This is why, despite being past retirement age, Hume took on the challenge of the new School of Dentistry in Utah, one he defined as “teaching students how to become dentists so they could help disadvantaged populations become healthy again, or stay healthy.”

“People don't realize that poor dental health leads to a lot of other health care issues.”

Senator Evan Vickers (R-Cedar City)

Central to that education has been the federal benefits program Medicaid. By collaborating with the Utah legislature and Medicaid to reignite oral health care for eligible groups, the school’s students have treated a volume of patients with complex dental needs that is beyond enviable for dental students at most other schools. Furthermore, the SOD uses data from Medicaid patients to pursue research on improving public oral health in conjunction with overall health.

“People don't realize that poor dental health leads to a lot of other health care issues,” says Senator Evan Vickers (R-Cedar City), a key participant in re-opening Medicaid Dental in Utah. “If you've got trouble with your mouth, oftentimes you can't eat appropriate foods,” he says. “It's harder to eat fresh vegetables, and you can't even chew. That leads to poor health overall.”

The SOD’s work on oral health care in substance abuse recovery “set the foundation for that integrated piece of focusing on overall health,” says Jeri Bullock, DDS, associate dean for clinical affairs. “That sets us apart, especially as we are bringing in new partners to open more clinics.”

In a former state-owned building in Rose Park, the SOD operates a small dental clinic. There it is exploring integration with U of U Health’s EPIC medical record systems and with its next-door neighbor, the Intensive Outpatient Clinic, to see how marrying oral health and medical care impacts overall health for low-income patients with chronic health conditions.

“The level of quality of oral health care in the state of Utah is improving dramatically as a consequence [of the school’s efforts],” says vice dean Glen Hanson, DDS, PhD, one of the founding faculty. Its approach has become known out-of-state as “the Utah model,” he says. “They're looking at it at the national and federal level to see how they can embrace the principles that have worked so well for us.”

A CAVITY IN NEED OF FILLING

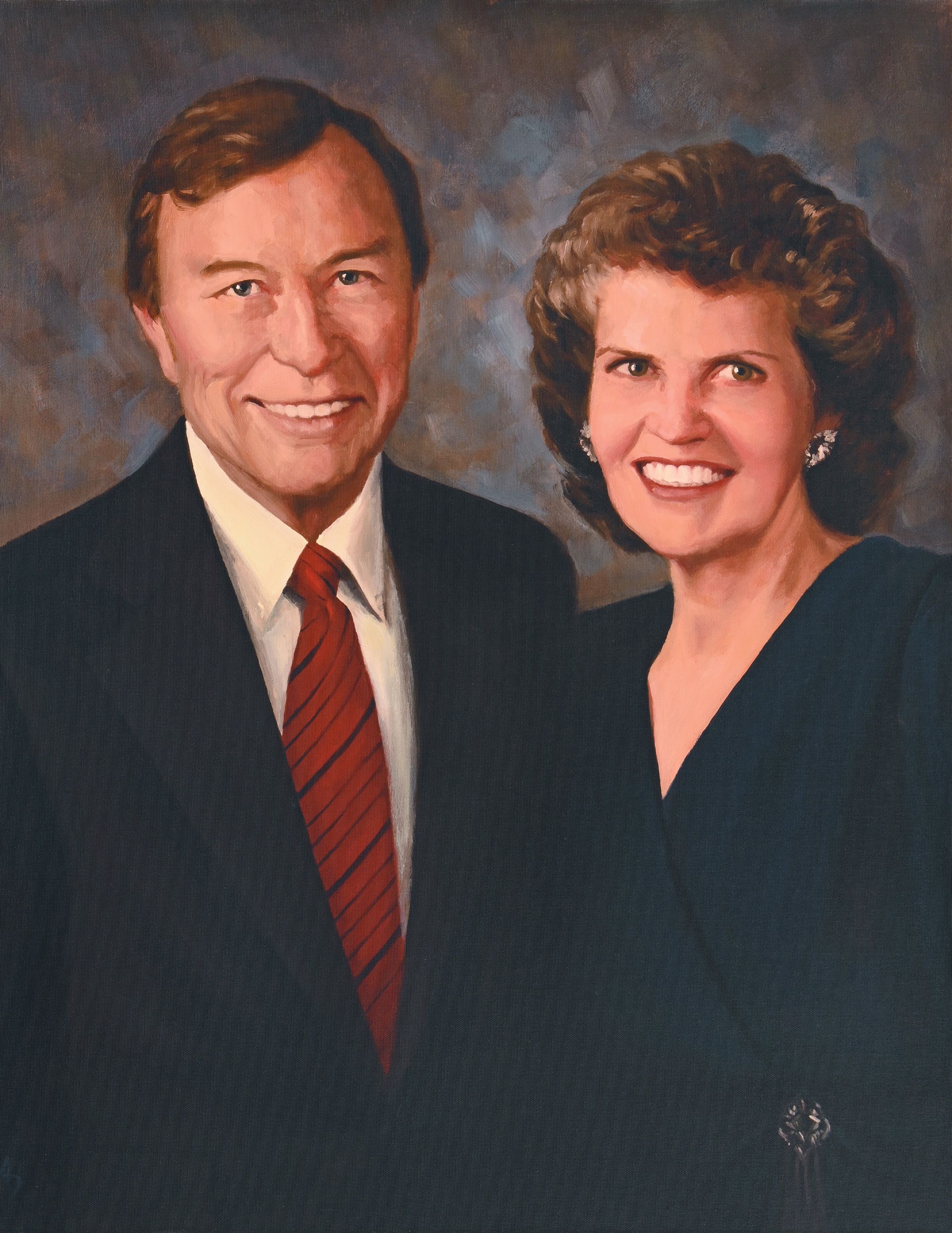

Tye Noorda knew well the devastation of not being able to access oral health care. Shortly after the one-time New York model married Ray Noorda—later the president and CEO of Novell Inc.—she fell and broke some front teeth. For a year, she could not get the dental care she needed.

Decades later, the couple donated $15 million to U of U Health for Utah’s first nonprofit dental school with the proviso that the school treat the underserved.

In 2013, the university broke ground on a site in Research Park that had been vacant for 35 years. Vivian Lee, MD, PhD, MBA, then-CEO of U of U Health, called it “the largest cavity in the world.”

Ray and Tye Noorda

Ray and Tye Noorda

Buoyed by $15 million in matching funds from religious institutions, the $30-million, 85,000-sq-ft Ray and Tye Noorda Oral Health Sciences Building, home to the new School of Dentistry, opened in February 2015.

But how, then, to fulfill the Noordas’ mandate? Then-interim dean Hanson’s answer was to pursue Medicaid.

As part of a state university, the SOD would leverage donations to pay the seed money needed to trigger federal Medicaid dollars for oral health care. The school’s students would then hone their skills treating Medicaid and other underserved patients under supervision from attending faculty.

The key was getting the legislature to agree. While Utah's state senators and representatives had never been fond of Medicaid or federal dollars, there was also a recognition, says Sen. Vickers, that preventive medicine saves the state money in the long run. Since restoring dental benefits came with no cost to the state, the House and the Senate got on board.

Tye Noorda, third from left, joins the August 2013 groundbreaking ceremony for the School of Dentistry building in Research Park.

Tye Noorda, third from left, joins the August 2013 groundbreaking ceremony for the School of Dentistry building in Research Park.

ADDRESSING A NEED

In February 2016, the legislature passed SB39, restoring Medicaid Dental benefits to 34,500 individuals with blindness or other disabilities. Vickers saw it as one of several pilots testing the SOD approach. It was the first of a number of bills partially restoring pieces of Medicaid Dental, nearly all of them sponsored by Rep. Steve Eliason (R-Sandy). “Without him, it wouldn’t have happened,” Hanson says.

What put the dental school’s Medicaid program on the map was the substance abuse disorder and recovery community. Hanson, a dentist and pharmacologist, had directed the National Institute on Drug Abuse. He had long thought that the impact of drug use, particularly methamphetamines, on oral health warranted research. A grant from two federal agencies focused on integrating primary and behavioral health care became the vehicle to investigate. Collectively, Utah nonprofits caring for people with substance use disorder (SUD)—First Step House (FSH), House of Hope, Odyssey House—pitched the idea of the dental school providing oral health care to nonprofit clients in recovery.

The grantors were fascinated. “This isn’t what we were thinking, but we love the idea of dental health care paired with substance abuse treatment,” FSH’s executive director Shawn McMillen recalls them saying.

"The FLOSS study showed that if SUD patients’ typically complex oral health needs were treated, they were two to three times more likely to get off drugs and find employment."

Glen Hanson, DDS, PhD

That early collaboration focused on 400 adults in recovery becoming patients of the school’s student dentists.

The results were astonishing. The FLOSS study (Facilitating a Lifetime of Oral Health Sustainability for Substance Use Disorder Patients and Families) showed that if SUD patients’ typically complex oral health needs were treated, they were two to three times more likely to get off drugs and find employment, Hanson says. Additionally, homelessness within the study group was almost completely eliminated. Most remarkable of all, given these treatment programs were court-mandated, clients stayed in treatment 100 days more on average than before.

“The program hit the mark, if not exceeded it,” McMillen says.

Hanson and SOD colleagues showed legislators the data and asked them to expand Targeted Adult Medicaid (TAM) to include dental benefits for people enrolled in substance abuse treatment. The legislature voted yes.

GETTING HIS SMILE BACK

The impact of substance abuse on teeth was apparent in Adam Davies’* smile. He didn’t have one. After his mother won custody when he was 11, Davies and his brother spent their teens homeless with her and their stepfather, both of whom used heroin and meth.

By his late 20s, Davies’ drug use was his life. At a job interview with an electricians’ union, he felt like a shoo-in because his family worked there. But a lack of basic nutrition had led to his teeth loosening or falling out. Wary of smiling lest he reveal the state of his mouth, he did not get the job.

“Those goals are important. They bind you to staying sober. Even when there’s a trigger and you’re thinking about relapsing, you think, ‘I’m getting my teeth soon,’ and it helps. It really does.”

Adam Davies*

Eventually, Davies had his teeth replaced with dentures. Within a couple of years, he left his “bottoms” in a crack house and lost his “uppers” running from the cops.

After several jail stints, Davies left incarceration wanting to change. He went to First Step House for medical and oral health screenings in Autumn 2023. The latter led to the School of Dentistry’s clinic, where a second-year student treated him.

Waiting for his teeth gave Davies another goal. “Those goals are important,” he says. “They bind you to staying sober. Even when there’s a trigger and you’re thinking about relapsing, you think, ‘I’m getting my teeth soon,’ and it helps. It really does.”

In January 2024, Davies, now in his early 40s, left the clinic with dentures and his smile. He went back to the electricians’ union for an interview knowing that while he would be judged on his work experience and abilities, his smile would seal the deal.

“A smile is just something that goes along with being human,” he says. “Getting it back allowed me to be myself a lot more, to be the person I knew I was inside.”

*A pseudonym. First Step House requested their client be anonymous in order to take part.

GETTING HIS SMILE BACK

In Kingsbury Hall’s second row, SOD graduate Ryann Lim’s thoughts wandered to the following morning, when she and other dental students would show children and teenagers from low-income schools what dentistry was about and why they should think about it as a career. She wanted to encourage youth of color to enter the profession. She had learned that even the simplest act—such as a morning talk with children—could change someone’s life.

It might also be calling 311 (non-emergency municipal services) to get rides for patients struggling to find transport to the clinic. Or providing a simple dental device that turns someone’s life around.

The latter was the case with a woman just out of prison for drug-related offenses. Her children shunned her, embarrassed by her looks. She came to her appointments in pajamas, self-consciously covering her mouth because of her missing front teeth.

The third-year student supervising Lim suggested a temporary dam with tooth-colored filling. Even though Lim thought the dam aesthetically unattractive, for her patient it meant the world. Instead of working an exhausting graveyard shift at a warehouse, she got a job in hospitality, doubled her income, and helped her children when they needed her. She bought a car and got a place of her own.

The power of simple deeds wasn't all she came to appreciate at the dental school. Lim also learned that provider consistency is essential for patients. A Ukrainian refugee family underscored that for her.

Fundamental to Sergii Ivanskyi was finding a dentist he had faith in and who could provide consistent care for him and his growing family.

Just two years before, Sergii had been a senior union official in Ukraine. In February 2022, wearing his best suit and holding a small suitcase, he stepped out of a taxi at an Azerbaijan airport only to learn all planes to Kiev were canceled. Russia had invaded. He called his wife Alexandra in their hometown Bucha—the site of an infamous Russian massacre of civilians—and told her to flee with their son and baby, who she was breastfeeding.

Ryann Lim with her UUSOD patient Sergii Ivanskii and family at his home.

Ryann Lim with her UUSOD patient Sergii Ivanskii and family at his home.

They managed to meet Sergii in Romania, then moved to Germany. Despite advanced degrees in both international relations and arts in the economy, he could not find a job in his field because such posts required fluency in German.

A Messianic Jew, Sergii’s curious mind had led him to debate faith online with two missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One of them reached out to say there was shelter and work in Utah. That felt like an answered prayer.

After settling in Utah, Sergii's status as an asylum seeker placed him on what he called “humanitarian parole,” which made finding work hard. They got food stamps and Medicaid for the family, but only his children had dental coverage. After an oral health screening at the Population Health Center's dental clinic in Rose Park, Sergii was assigned to Lim at the SOD clinic. He needed numerous fillings. From the beginning, Sergii was struck by Lim’s patience and thoughtfulness.

Through the dental school, he successfully applied for funding from the Oral Health Assistance Program (OHAP), which pools donations to support those needing dental work who aren’t eligible for Medicaid dental benefits. OHAP covered him for six fillings and a crown.

He had numerous fillings and wisdom teeth extractions, along with needed crowns. In Ukraine, Sergii had to bribe doctors and nurses to get care. He was so impressed by Lim’s thoroughness and skills that he wanted her to handle the rest of his treatment.

Lim also treated Alexandra, putting on a crown for her when she was 37 weeks pregnant.

When Lim told Sergii she would graduate soon, he said, “We’ll go wherever you go.”

“NOT YOUR MOTHER'S MEDICAID”

By summer 2023, the School of Dentistry had 70,000 Medicaid potential dental patients, roughly a third of the state’s total eligible adults.

In the 2024 legislative session, the legislature signed off on Vickers’ bill SB29, co-sponsored in the House by Eliason, to provide the remainder with dental benefits. That would take the population to 220,000, far more than the SOD and its annual class of 50 students could hope to treat or have access to, given Utah’s size and the remoteness of its rural communities.

Addressing Utah’s need for Medicaid dental services came through partnerships, says Bullock, who runs the school’s eight clinics, which stretch from Ogden to St. George and all along the Wasatch Front. “We're doing a lot of great things, but not alone,” she says. “It's community partnerships. It's working with the state.”

Several clinics were formerly state-owned. In 2020, the state offered the school its last dental clinics in Ogden and Rose Park, along with the state mobile van and millions of dollars in equipment.

“The process was streamlined, the compensations were better. Utah Medicaid is not your mother’s Medicaid. This is different.”

James H. Bekker, DMD

Associate Dean of Professional, Community, and Strategic Relations

With scarce dental resources in rural counties, which make up 77 percent of Utah’s land and 12 percent of its population, providing Medicaid-eligible adults with treatment was at the heart of the dental school’s plans. The Associated Provider group. was developed in the first years by G. Lynn Powell, DDS, the school’s honorary founding dean. Any Utah dentist could affiliate with the group and sign up to treat Medicaid patients.

James H. Bekker, DMD, associate dean of professional, community, and strategic relations, took over developing the group. His team worked with Medicaid to improve rates, at least for preventive care.

“The process was streamlined, the compensations were better,” Bekker says. With help from Powell and the Utah Dental Association, Bekker and his team began a public awareness campaign to educate the state’s dentists that contemporary Utah Medicaid “is not your mother’s Medicaid, Bekker says. “This is different.”

TO GIVE IS TO RECEIVE

Tremonton dentist Kay Christensen, DDS, signed up in the first year of the Associated Provider group. He did so more out of an urge to serve than the prospect of improved Medicaid rates. Tremonton is a rural town in Box Elder County, located in Northern Utah. Christensen has owned his own practice for over 30 years and believes dentistry is service-oriented.

“Dentists oftentimes are givers, particularly here in Utah,” he says.

In his early years as a provider, Christensen took Medicaid patients. “When you put it down on paper, it costs money to see a Medicaid patient, with the overhead expenses,” he says. As his practice grew, Christensen decided not to take any more Medicaid patients than he already had. After a while, though, he felt an obligation. “Someone needed to be there for them.”

As a former president and ongoing board member of the Utah Dental Association, Bekker traveled around Utah attending Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) meetings in restaurants and small conference rooms with local dentists from Ogden to St George, Garrison to Moab. Bekker encouraged them to join the Associated Provider group and introduced them to Christensen, a fellow UDA leader, as someone who found value in the affiliation.

As more dentists joined, word of mouth helped fuel growth. By 2024, 25 percent of Utah dentists—430 in total—had signed up. Even so, Bekker was frustrated that the message of Medicaid compensation being equal to or better than some insurance companies dentists worked with had not gotten through.

A PATIENT FOR LIFE

One of eight dentists in Tremonton, Christensen is the only Medicaid affiliate. Christensen felt that resistance to Medicaid among his colleagues stemmed from outmoded stereotypes that Medicaid doesn’t pay enough or that the patients no-show.

Christensen’s wife pointed out to him that oral health care for Medicaid patients often helps change their lives in terms of finding work, a home, and stability. “They’ll end up either being able to self-pay or have some other dental benefit plan,” she told him. Such patients, grateful the Christensens had taken them in, wanted to continue coming to their practice.

“They may be a patient for life,” he says.

“It’s the highlight of their week coming to see the dentist. We are their family and friends.”

Drew Gilley, DMD

Drew Gilley, DMD, is a dentist at the federally qualified nonprofit Mountainlands Family Health Center in Vernal, a small town in Northeastern Utah with a long history of oil and dinosaur bones. He is also an Associated Provider group member who knows where Christensen is coming from. His core patients, those with special needs and disabilities, “are loyal people,” he says. “It’s the highlight of their week coming to see the dentist. We are their family and friends.”

Out of 14 local dentists, only he and a handful of other offices accept Medicaid. Such is the demand from Medicaid patients for dental services that he’s booked out six months in advance. Before he took on a partner, it was a year.

Despite some problems, Gilley says the system had streamlined. “Way more providers are willing to take on U of U Medicaid patients,” he says. “I’d encourage them to take on U of U Medicaid and become affiliate dentists. It’s very rewarding.”

TO LOSE A PIECE OF YOURSELF

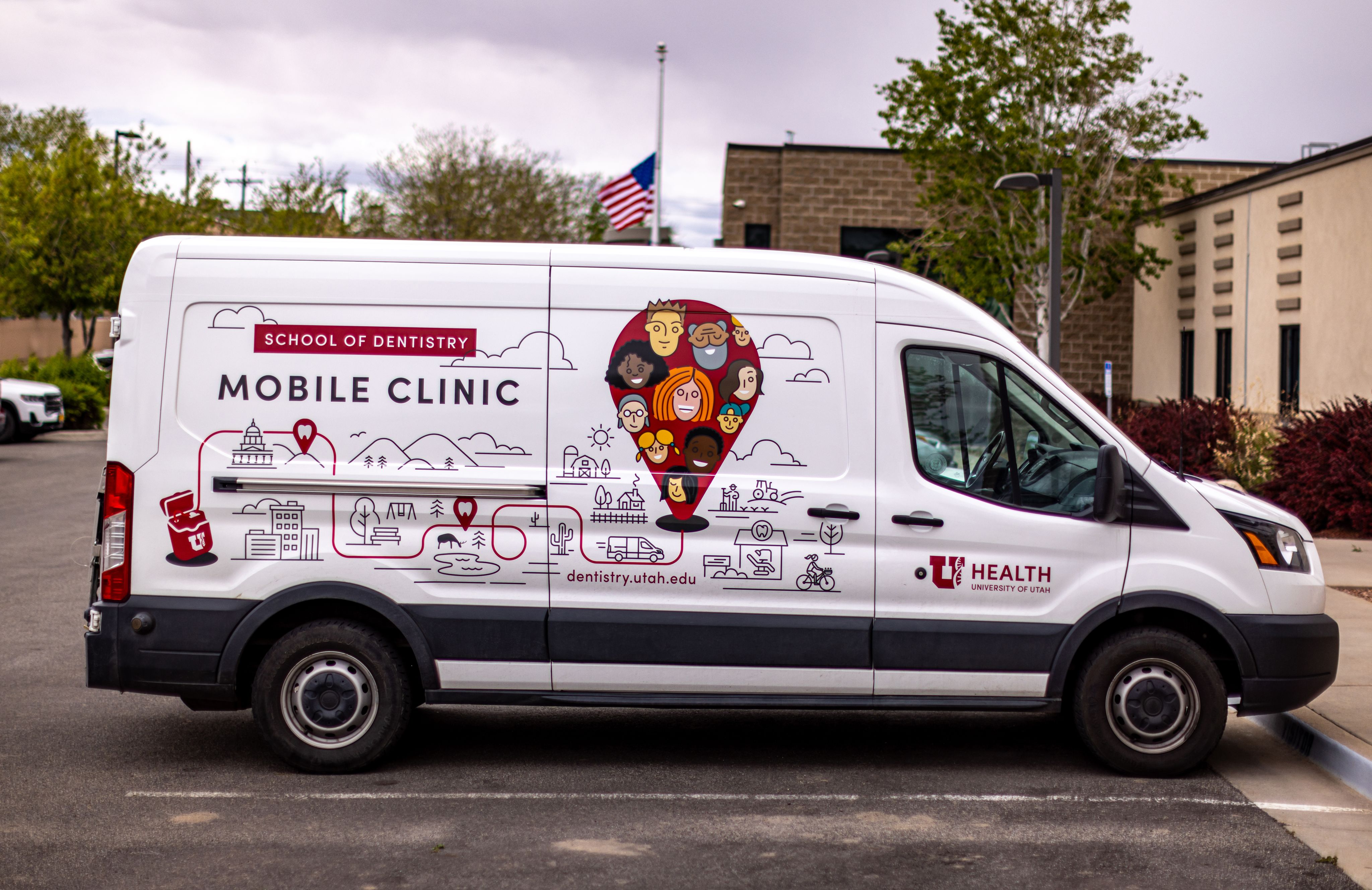

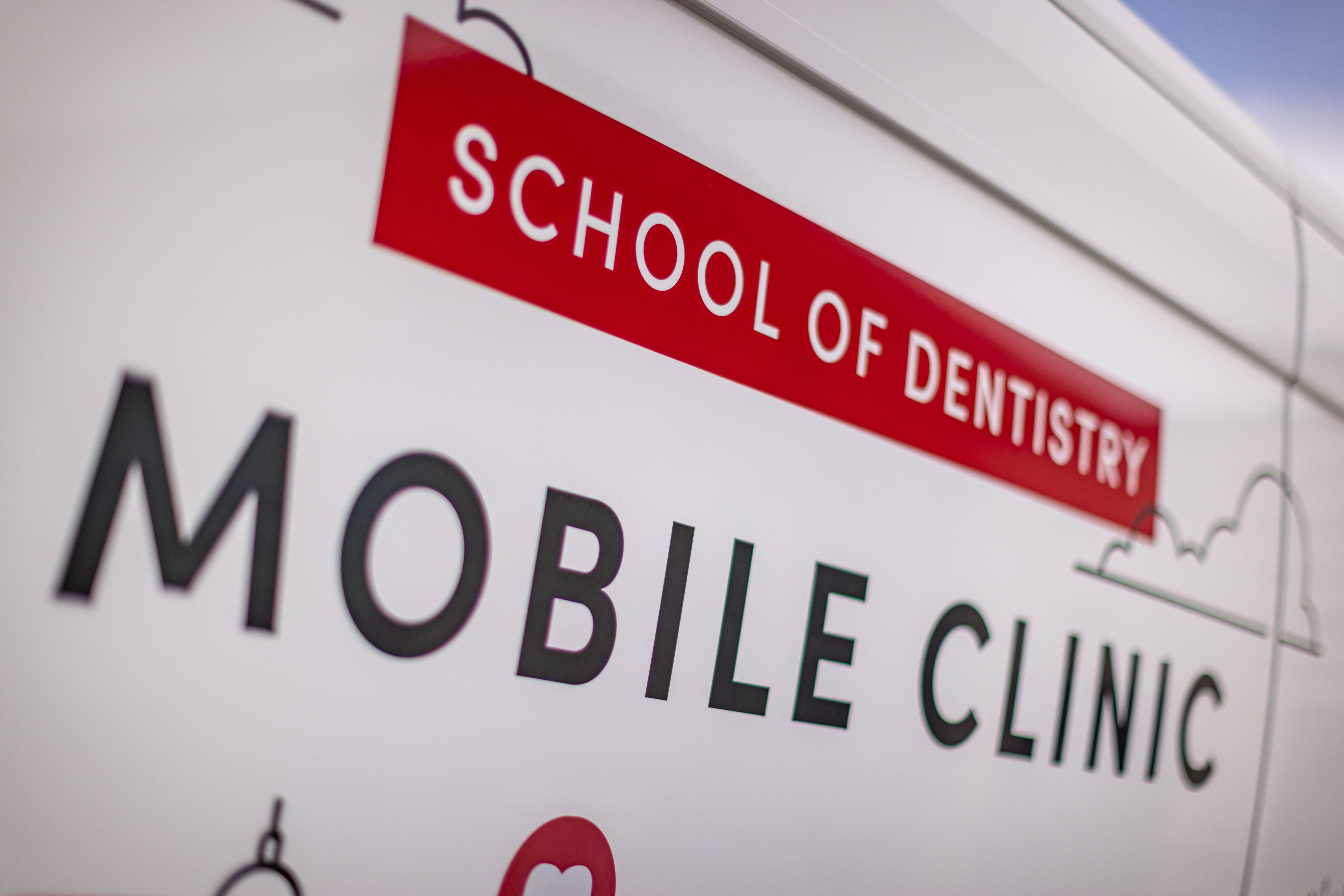

The School of Dentistry has another tool to expand oral health care coverage. In 2021, the school restarted the formerly state-owned mobile clinic program with help from a state Health & Human Services grant. The van currently visits nine rural towns a year, providing free exams, cleanings, fillings, and extractions for the uninsured over the course of a week.

Mobile Clinic Van

Mobile Clinic Van

On a Sunday in May 2024, administrative manager Steve Delsie and dental assistant Kate Kapinos drove the van to Vernal. They set up two red, reclining chairs along with instruments, a portable x-ray, and other equipment in a large office space at the back of the TriCounty Health Department building.

On Monday, Arman Farhadtouski, DDS, joined them as the first of two providers.

“Seeing her lose a part of herself because of our lack of resources was a very formative experience for me.”

Arman Farhadtouski, DDS

As an undergraduate, Farhadtouski wanted to serve Utah’s marginalized by becoming a dentist, a desire shaped by his own upbringing. Along with his mother and younger brother, Farhadtouski came to Utah as a child refugee from Iran in the summer of 2001. For five years, his mother, who spoke little English, raised the boys alone and without insurance. When Farhadtouski was 12, his mother’s tooth pain became so bad, it forced her to attend a free clinic. A volunteer dentist could only extract the problem tooth because the decay had been left untreated for too long. The look of shock on her face afterwards still haunted him.

“Seeing her lose a part of herself just because of our lack of resources was a very formative experience for me.” His mission, he says, was “to lessen the number of people that experience what I felt my mother went through that day.”

Day one of the Vernal clinic was dedicated to screenings. On Farhadtouski’s list was a young family with several children. The father worked in oil. “Work is hard to come by,” he told Delsie. They had hit hard times. Every day was a struggle.

The children had CHiP, but the parents had no insurance. Their oral health care had to be postponed indefinitely, they told Delsie, in favor of feeding and clothing their children. The father in particular was in rough shape. He had several broken teeth and a chronic abscess oozing infection from the inflamed gum.

Steven Delsie, mobile outreach, clinic manager.

Steven Delsie, mobile outreach, clinic manager.

Kate Kapinos, lead dental assistant, mobile outreach.

Kate Kapinos, lead dental assistant, mobile outreach.

Arman Farhadtouski, DDS

AArman Farhadtouski, DDS

Heidi Iongi, DDS

Heidi Iongi, DDS

“I’ve been living with this pain a long, long time,” he said. “I just don’t have any other options.”

The young father’s desperation and suffering struck a deep chord with Farhadtouski, who saw his own mother in his anguish. Just like these parents, she had sacrificed so much so that her children could have a life she had not had. He also saw her in the man’s near-despair at the state of his mouth.

After the screening, Farhadtouski arranged an antibiotic for him to calm the infection so they could treat the broken teeth later in the week. That still left the fillings.

The next day, the father was first in line. There was a complication. The young man had a deep anxiety about dentistry that bordered on near-terror. Farhadtouski did his best to calm him, the patient’s anguish touching him deeply.

Farhadtouski did three fillings, and the clinic booked the father in for an end-of-week appointment with the second provider, Heidi Iongi, DDS.

Iongi took out the broken teeth and cleaned out the infection site. The clinic team educated the parents about oral hygiene and resources they could access to get more care. But there were some things they could not help with, such as replacing the missing teeth.

For Farhadtouski, at the end of the day, as he sat in the car decompressing before heading back to his hotel room, what came back to him was the achingly sincere gratitude of the father. “We can’t change the world in one day,” he thought. “But we can change, hopefully, the world for that one individual that day.”

TOUGH CHOICES

Before Farhadtouski left for Salt Lake, he and Iongi, who is also the dental school's director of community engagement and clinical integration, visited Gilley, whose offices were in the same building. They wanted to say hello to the Associated Provider group member and, if necessary, refer patients in need of follow-up care.

The Vernal dentist appreciated getting a heads-up that the van was there that week. Gilley spelled out the reality of dentistry in his town. As he saw it, there are two paths for dentists: see people with insurance like he did, or see people willing to pay the full fee. The latter dentists, he says, are booked two months out.

Iongi said they wanted to support him and his practice partner. Gilley replied that he had patients coming in without insurance or money, and he had nowhere to send them. If the School of Dentistry could give him a heads-up when the van would be coming, he said, “I’d love to give them the option of waiting to see you guys.”

The prospect of full Medicaid expansion in early 2025 concerned Gilley. “I’m nervous as all get-out on that,” he said. He feared that with the lack of dentists willing to take Medicaid patients in Vernal, he would be under pressure to make hard choices. “Do I have to pick and choose whether I help this 8-year-old or 44-year-old? I shouldn’t have to play God. Tooth pain is excruciating, and to tell someone, ‘I don’t have a way to get you in,’ is just plain hard.”

"I don’t think anybody has the vision that day one it’s gonna be everybody. It's a work in progress as we line up more dentists to be part of the affiliate program.”

Senator Evan Vickers (R-Cedar City)

While the huge demand among the underserved in Utah for adult dental services is undeniable, particularly when compared with the number of dentists in the Associated Provider group, Sen. Vickers doesn’t anticipate a tsunami of patients knocking on Medicaid dentists’ doors.

“I don’t think anybody has the vision that day one it’s gonna be everybody,” he says. “It's a work in progress as we line up more dentists to be part of the affiliate program.”

Bullock says Associated Provider group members would be crucial for the future success of the school if Utah expands statewide Medicaid coverage. “We have to lean on them to reduce these barriers to access to care in a meaningful and sustainable way,” she says. “We don't want this to be frustrating for patients. We want this to be sustained long-term for decades to come.”

Sen. Vickers agrees. The provider group is key. “It’s not perfect,” he says. “But where they have been successful in getting those partnerships, it’s providing care that we haven’t had before.”

The young father and his family Farhadtouski and Iongi treated through the mobile clinic in Vernal were exactly the kind of people who would benefit from full Medicaid expansion.

“It would be a complete game-changer for the Vernal family and their children,” Farhadtouski says. That comes with a caveat: as long as they can find dentists near them who take Medicaid.

LIVING IN THE SHADOWS

After Hume's initial welcome to commencement, he introduced Utah’s director of Medicaid, Jennifer Strohecker, as the keynote speaker. She drilled down to why the underserved were so important. As a 24-year-old pharmacy student at an ER in a low-income Philadelphia neighborhood, she witnessed a patient the same age as her die from an asthma attack because he couldn’t afford an albuterol inhaler.

Twenty years later, she still felt driven, she told the SOD graduates, to ensure “affordable and accessible care for all.”

She recalled the decade-long wilderness of no dental care for Medicaid patients and how from 2018 onwards, the SOD and state Medicaid had forged “a strong and strategic partnership rooted in our commitment to care for all members of our community.”

Leverage, she said, “the tools of a change agent—your heart, an open mind, and a willingness to serve. In an economically affluent state like ours, true success is measured by how well we lift up the least among us.”

Alex Rojas giving his commencement speech to his fellow 2024 graduates.

Alex Rojas giving his commencement speech to his fellow 2024 graduates.

Toward the end of commencement, Alex Rojas left the anonymity of the three rows of fellow graduates to give his commencement speech. He picked up on similar themes to Strohecker.

Rojas told his peers how the people he had met in his life had shaped who he had become. “The man I am today knows that each patient I treat deserves to be treated as an individual, with hopes, fears, and challenges unique to them,” he said.

Rojas was born in Mexico. His mother had a U.S. work visa and brought him at age 5 to California in 1999. Her husband followed, and they moved to Utah. Undocumented and fluent in Spanish, unlike his two U.S.-born brothers, Rojas had to grow up quickly, translating for his parents with landlords about being unable to pay the rent.

Along with no papers, Rojas had no health insurance. “I feared getting in trouble, and I feared getting hurt,” he says. His parents didn’t teach him oral hygiene, and a high-sugar diet led to dental issues. “I was one of those kids with silver crowns on all their teeth because my dental care was not good.” The family found a Springville dentist willing to trade dental care for Rojas’ mother cleaning his large house. The Rojas family was grateful. “I thought that was really inspiring,” Rojas says.

In fall 2016, after finishing a church mission and working to pay off debts, Rojas started his first year at the School of Dentistry. Rojas’ goal was earning a living wage to support his own growing family and his parents.

“IF YOU FIND A GOOD DENTIST, STICK WITH THEM”

One example of Rojas’ desire to see patients as individuals is Starr Avray. Diagnosed with debilitating Lyme disease, the 42-year-old attorney and social worker was underserved because of her chronic illness, Rojas explains. She was trying unsuccessfully to get dental treatment that would address her root problems of polypharmacy (the corrosive impact of medication on her teeth) and periodontal issues.

In 2020, she had “a horrible, horrible experience,” she said, with a private dental clinic. A generalist dentist limited in experience and knowledge when it came to tackling her complex problems only made her problems worse. He put in a bridge to replace missing teeth, but six months later it fell out. She paid for it to get redone. Again it fell out, so she threw it in the trash.

“I was done,” she says. “I didn’t care. I completely gave up.”

Rojas with patient Starr Avray post-graduation ceremony.

Rojas with patient Starr Avray post-graduation ceremony.

In May 2023, while visiting her psychiatrist at their office in Rose Park, on a whim Starr signed up with the SOD's dental clinic next door. At her third appointment, she met Rojas. They bonded over shared histories as immigrants and children of immigrants. “His bedside manner was just on point,” she says. She wanted him as her dentist.

“My mother always told me, ‘If you find a good dentist, stick with them.’”

Starr Avray

Rojas talked to his attending about, as Starr put it, “adopting me. I’m not an easy case at all. I’ve been here ever since.” For the next eight months, Rojas worked on rebuilding Starr’s mouth.

Days before commencement, Starr came in for her last dental appointment so Rojas could cement a crown in. He wanted to make sure the crown fit and color-matched perfectly.

Rojas had a 3D model of her new teeth.

“That’s mine,” Starr exclaimed, reaching for it gleefully.

Ninety minutes into the visit, Starr was alone in the cubicle, studying the 3D model in her hand, like Hamlet contemplating Horatio’s skull. Its beauty—there was no other word for it—testified to how fate had delivered her to Rojas. The alternative may well have been dying a few years later from a dental infection for not seeking further treatment after throwing away the defective bridge.

“I dodged a bullet,” she thought, relieved. “Idiot, for being so stubborn.”

TOP OF THE CLASS

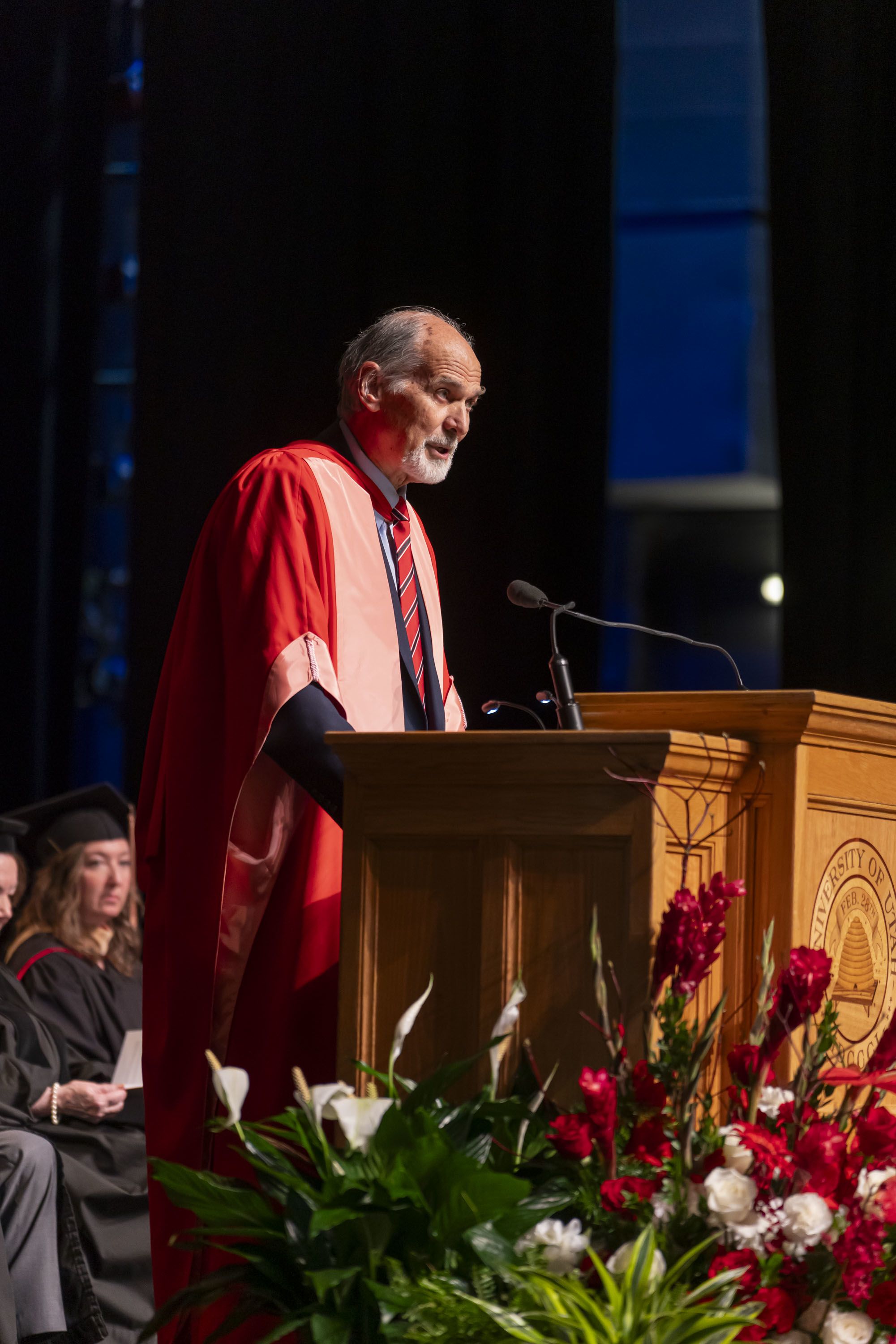

As Hume began his speech at the graduation ceremony, he observed that the graduates departed the School of Dentistry “as, without any doubt, the most highly clinically experienced and clinically skilled graduating class in the United States this year, or, I believe, in any year.” He added that the students had provided more high-quality care to more patients and performed more procedures “central to the practice of excellent dentistry than any class in the nation.”

Dean Hume speaking to the school's 2024 graduates.

Dean Hume speaking to the school's 2024 graduates.

The students stood on command, switched their tassels from right to left on their mortarboard caps, and one at a time mounted the stage to receive their diplomas as newly minted dentists.

Afterward, in the balmy late spring afternoon, they gathered with family and friends under white awnings on the lawn in front of Kingsbury Hall to celebrate, hug, and wish each other the best.

Rojas would be joining a 20-year-old private practice in West Jordan. His goal was to become more confident as a clinician.

In preparation for working at community health centers (CHCs), Lim’s plan post-graduation would be to do a U of U Health residency, six months at the hospital and six months at the Greenwood Health Center in Midvale to learn in detail how to care for the kind of vulnerable populations she would find at CHCs.The choice made her patients happy.

In April 2024, Lim texted Sergii, “Greenwood Clinic in Midvale. Starting in July.”

He wrote back, “Ryann I am following you.”

The night before graduation, Stephan had received numerous awards at the Dean’s dinner, including for leadership, dental public health, and community service activities. Hume praised “her experience serving the underserved, [which] set an example for her classmates of how to treat patients from diverse backgrounds. She worked behind the scenes to support and organize events that focused on those who have dealt with the disparities of health care in the past. She lifted her classmates, and other students, to understand the importance of health care for all.”

Stephan’s plan post-graduation was to move to Denver for a one-year advanced general dentistry course and then, like Lim, spend her career working in community health dentistry.

She recalled chatting to a proctor after an exam and telling the woman her plans. The woman looked horrified and said, “Why would you do that? There’s no money in it.”

To Stephan, working in a CHC that integrates care with medical, social, and mental health services and has a pharmacy onsite to help patients comprehensively with their health and quality of life was her life’s goal. It made absolute sense.

“That’s why I came into dentistry in the first place,” she says. “To care for people who have nowhere else to turn.”

EDITORIAL CREDITS

Stephen Dark – Writer

Wesley Thomas - Designer

Suzanne Winchester – Editor and producer

Jesse Colby – Art director

Nick McGregor – Copy editor

Geoffrey Fattah – Consultant

Aaron Lovell – Editor

PHOTO CREDITS

Charlie Ehlert – portraits of Dean Hume, SOD simulation laboratory, and Mobile Outreach Clinic.

Miguel Mendoza – portraits of SOD graduation (students, faculty, and ceremony).

Noah Jurik – portraits of Ryann Lim, Sergii Ivanskii, and family.

Kristan Jacobsen – graduation portrait of the SOD class of 2024.