The Healer’s Art

For advanced cancer surgeon Laura Lambert, hope is the best medicine

By Stephen Dark

January 26, 2023

Nate Hardy never got sick.

The 41-year-old energy sector executive, who lived with his family in Farmington, Utah, never caught the colds that Natalie, his wife, got from their five children. Nothing put a crimp in the farm-raised, passionate outdoorsman’s stride. Until, that is, on February 2, 2012, when, burning up with fever, he was forced to lay on the bathroom floor in search of relief from abdominal agony.

Natalie waited for three hours while an elderly surgeon operated on Nate to identify a huge, mysterious mass in his abdominal cavity. When the surgeon came out of the OR, he told her it resembled appendix cancer, a rare condition he had seen only once in his 1970s residency. For still-unknown reasons, in a few hundred people a year, the appendix abruptly turns on its host, generating sticky, apple jelly-like mucinous tumor in such volume it starts to shut down organs in the abdomen if not removed. The surgeon pulled out four quarts of tumor from Nate’s belly and sent samples to his hospital’s pathology department and to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, which then had one of the few appendiceal cancer programs in the country.

On February 9, 2012, Nate received confirmation that he had appendiceal cancer. It brought some—albeit marginal—comfort. “At least we know what we are fighting,” Natalie thought. But it didn’t prepare the Hardy family for what came next.

The more people they talked to about Nate’s cancer, the more they felt they were running out of hope. Nate had six months to live without treatment—or two years to live with treatment, one doctor predicted. Another told them, “Go home and enjoy what time you have together.” Nate’s medical oncologist told them, “I wish I could tell you most patients don’t die from this, but I can’t.” Then he laughed nervously. The Hardys looked at each other.

At a follow-up meeting, the oncologist said he’d never treated appendiceal cancer before but suggested chemotherapy as with any other cancer. Natalie knew enough about the disease to know that wasn’t true.

A patient advocate told them about an aggressive surgical procedure called Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) and gave them a list of 14 U.S. specialist surgeons. HIPEC is a multiple-hour surgery where the patient’s abdomen is opened from sternum to pubis. Then, the tumor is delicately sculpted out from around the stomach and other organs. For 90 minutes, hot chemo fluids wash through the abdomen to kill any remaining cancer cells.

The Hardys sent Nate’s results to seven HIPEC specialists and spent months trying to get someone to talk to them. Surgeons and nurses were difficult, opaque in their language, unhelpful, or non-responsive.

The only hope they had was Nate’s willingness to fight. Two weeks after his surgery, to the disbelief of his colleagues, he was back at work. He underwent chemo every two weeks and stayed busy, playing golf with friends, coaching his kids in baseball, rock climbing, restoring a 1971 dirt bike with his 16-year-old son, hiking with the family, and fly fishing.

He didn’t discuss his feelings, and his ability to compartmentalize amazed his wife. “Just cry, just scream, just be mad,” she’d say to him. “Why?” he’d reply. “I’m dealing with what I have.”

After four months of frustration, refusals, and, in some cases, condescension, one Saturday morning in June 2012, while working on a chicken coop in their backyard, they received a call from Laura Lambert, MD, a HIPEC surgeon at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, Massachusetts. They had sent a packet of Nate’s results to Lambert, and for the first time, someone in the medical community offered hope.

“We’re just going to try this, we’re going to do the best we can. And we’re going to give you as much time as we can.”

—Dr. Laura Lambert

An Existential Abyss

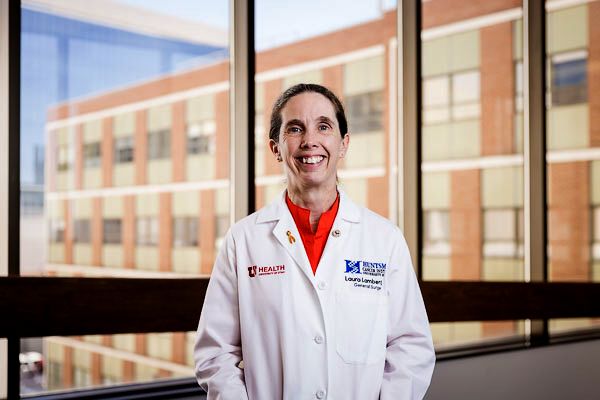

Today, ten years after meeting the Hardy family, Lambert is a surgical oncologist and professor of surgery at University of Utah Health. She directs the peritoneal malignancy program at Huntsman Cancer Institute and runs the surgical residency program at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine.

If modern medicine has redefined itself around “taking care of problems” in ever-smaller, more specialized parts, Lambert is “completely committed to doing right by her patients,” says Joan Bengtson, MD, a retired OB/GYN and longtime mentor to Lambert. “She is dedicated to having them be the focus of everything that we do.”

For Kenneth Eckhert III, MD, a Buffalo, New York-based community surgeon who has known Lambert for more than 30 years, what drives his friend and philanthropic partner is simple: “She just does what she feels is right from her heart.”

That’s true whether it’s rescuing abandoned stuffed animals or becoming board-certified in palliative care to help people she can’t support through HIPEC, says Lambert’s husband, Joe Glover. “It’s all based around helping somebody—even if that somebody is a little ragdoll.”

The root of Lambert’s drive can be traced back to an operating table in an impoverished Haitian hospital. For Lambert, her ideal of service–whether to stage four cancer patients and their families or the poorest of the poor in Limbe, Haiti–is built on an understanding of the role hope plays in medicine. “I’ve come to recognize that hope is as vital to living as oxygen,” she says. “You take it away, people can’t breathe. They feel like they’re dying.”

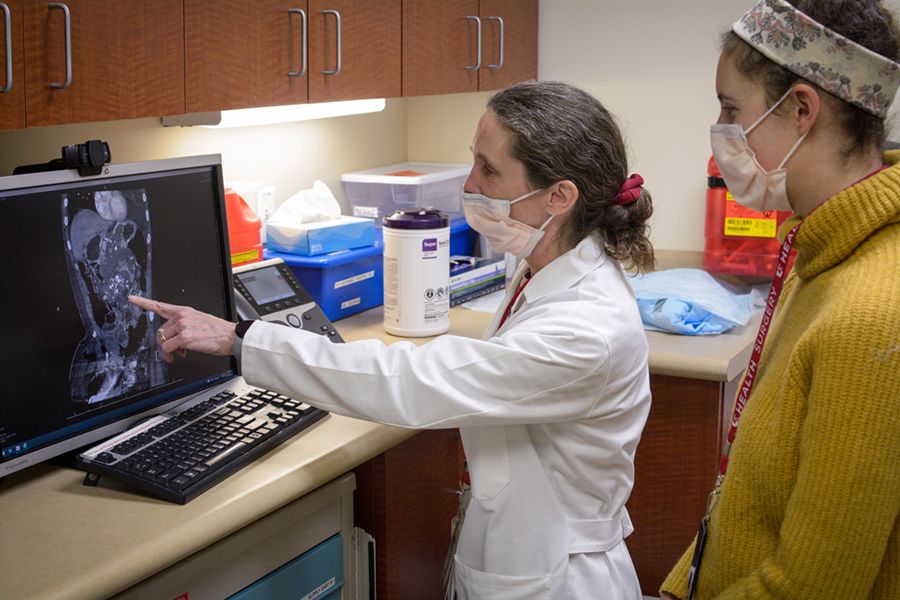

In the process, Lambert has embraced her vocation not as a surgeon treating cancer but as an oncologist who views surgery as just one tool to treat the disease. Other tools include palliative care, something surgeons typically disdain as defeatist, and end-of-life hospice care to support patients for whom HIPEC is not an option. She’s also studied existential humanistic psychotherapy to better understand the experience and meaning of death.

In her relationship with Nate and Natalie Hardy, Lambert ran the gamut of her career, performing two HIPEC surgeries on him at UMass and then five more operations at Huntsman Cancer Institute at University of Utah. She went from a self-doubting but committed surgeon when they first met to someone who was increasingly confident in her chosen vocation and skillset to a physician who could steer Nate from HIPEC to palliative surgery to hospice and, in honoring his last request, supporting his widow. In essence, Lambert fought his cancer as long as she could, then accompanied him and his family as they peered daily into the existential abyss of his impending death.

That’s why people like Nate and Natalie “need hope to exist,” Lambert says. “And while I don’t give people false hope, I do everything I can to give them something to hope for.”

WELCOME TO LIMBE

Lambert had no plans to be a doctor, even though her father, Donald Lambert, is an anesthesiologist and her mother, Mary Lambert, an OR nurse. It was her father’s long hours working weekends and holidays to become an anesthesiologist that convinced her medicine was the last thing she wanted to do. “There’s nothing worth working that hard for,” she thought. By the spring of 1990, the U.S. national skier and college graduate was set on getting a PhD in German from a liberal arts college. Fate, however, had other plans. That summer, her parents volunteered to go on a week-long surgical mission with a surgeon, Ken Eckhert II, and his high school son to a hospital built in 1953 in northern Haiti. They invited her to go along.

At the time, The Hospital of the Good Samaritan saw 6,000 patients a month with 40 beds, four to a room, and—in lieu of air conditioning—open, unscreened windows. There was no oxygen or suction in the rooms and no ICU or blood bank in the hospital. Patients brought their own linen and pillows, and their toilet was a basin that a relative emptied for them. There was also an orphanage with many babies and children with disabilities. Each year, when Lambert got to Limbe, she’d steel herself to visit the children and touch their hands, their faces lighting up with smiles at human contact even if they couldn’t focus or were non-verbal.

Shortly before they arrived that first summer, the hospital announced on the radio that a surgical team was visiting. Each day, 25 to 30 people dressed in their best clothes would wait in the baking sun to be seen in an exam room that was little more than a closet with dim light and a rusty bed.

The Vermont-raised Lambert marveled at life in Limbe. The congestion of mopeds, bikes, and motorbikes on streets without traffic lights; the smell of mounds of garbage on which pigs rooted; running sewage in the streets; women cooking on charcoal in 100-degree heat. And yet there were glimpses of normalcy: a parent walking her child to school in a sparkling white shirt, two laughing men playing dominoes by the roadside. Lambert would tell friends, “It just rocked my whole world.”

The emotionally exhausting week of surgeries seemed to last forever—and, for the last 30 years, Lambert has returned to Limbe for the same wrenching, inspiring experience. That first visit, she was mostly a runner and assistant to her parents, although she scrubbed in several times to observe and help. Eckhert invited her, under his supervision, to slice open an abscess. She watched, fascinated, as pus oozed out.

“I have to do something where I'm giving back to society for the rest of my life.”

At the end of the week, Eckhert pulled her aside. “If you’d consider a career in medicine, I think it would be a really good fit.” She thanked him but remained wedded to a liberal arts future. Back in Massachusetts, she worked a summer job at an upmarket bakery. A customer drove up in an expensive car and bought several hundred dollars of pastries. But when she learned they had sold out of lemon poppyseed muffins, the furious customer berated Lambert.

“I’m sorry, I can’t help you,” she told the astonished customer through her tears. “I have to go to medical school.” Until that moment, she’d had no idea she wanted to be a surgeon. But Haiti had broken her heart. “I have to do something where I’m giving back to society for the rest of my life,” she told herself. “I can’t go on living ignorantly and selfishly after that experience.”

A HAIL MARY PASS

As a student at Harvard Medical School, Lambert wondered what could she do in surgery that would be as fulfilling as her annual week in Haiti?

The answer emerged when she was a first-year surgery resident at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire. A young patient diagnosed with esophageal cancer asked her, “Why did this happen to me?” Lambert experienced an intense need to relieve his suffering. She had had similar feelings in Haiti when patients had to be turned away because the hospital had no resources for essential after-care. Might advanced cancers be the direction she was seeking?

The standard teaching during residency was that carcinomatosis—where cancer spreads through the abdominal cavity from its initial site—was a death sentence. You didn’t operate on it unless there was a bowel blockage from the cancer you could fix. But during the last three years of surgical oncology fellowship training at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, Lambert discovered what she called the medical equivalent of “a Hail Mary pass” in the embryonic form of HIPEC surgery. She wanted to make a career out of HIPEC—despite very rarely being a cure, it offered hope to cancer patients.

Not that her initial experiences were promising. In HIPEC’s early years, identifying those who would benefit and those who wouldn’t wasn’t easy. The surgeries took 12 to 20 hours and were only performed once a week, on Tuesdays. The first three Tuesdays of October, Lambert and her mentor opened up the scheduled patient, only to find the cancer too advanced. They closed up the incision and the older surgeon told the family surgery was not an option.

“Oh my gosh. How can anyone do this?” she thought. “This is so depressing.”

On the fourth Tuesday of October, her perspective shifted. During a 12-hour operation, they were able to remove all of the patient’s cancer, do the chemo wash, and then close things up. Lambert felt they had cheated cancer. She was so excited she could have jumped over the hospital. That was when she knew this was her calling.

CHANGING LIVES ON A BUDGET

If her youthful experiences in Haiti had sent her on this medical journey, her annual return trips to the same hospital—what she called a “long-term, short-term mission”—provided her with a wellspring of experience and insight. The trips also informed her growth as a surgeon and human being. When Joe Glover first met his future wife just before she started medical school, he realized that she fundamentally knew what she wanted to do with her life. Telling him about Haiti, it was quickly apparent that, in Limbe, Lambert had discovered people who truly needed help—and her own deep-seated need to help others.

Her parents and Eckhert became friends, as did Ken Eckhert III and Lambert. She started learning Haitian Creole to better communicate with patients, and the multi-generational mission traveled every year until Eckhert retired and the elder Lamberts stepped back. Then Lambert and Eckhert III, who like her went into medicine—in his case as a community surgeon—took over the program. Like Lambert, Limbe forged Eckhert III’s commitment to medicine as a vehicle to help others. He was devastated when the team didn’t have time to treat a Limbe boy who had an enormous thyroid mass and had waited all week to be seen by the surgeon. His father told the child, “You’re first on the list next year.” The next year, the child was at the front of the line.

“In the limited time we have with the limited resources that we have, who can we help the most?”

Bengtson felt similarly moved when Donald Lambert invited her to Haiti in 1993. “It was what I thought medicine should be all the time.”

The toughest challenge was having to select who they treated. With every patient they examined, they had to ask themselves, “In the limited time we have with the limited resources that we have, who can we help the most?” In advanced cases such as cancer, where essential follow-up care was not available, the patient’s family was told they could not help their relative. It was then left to the family to inform the patient.

In 2013, the team saw one woman in her 40s who had lived for 20 years with a vesicovaginal fistula—an abnormal connection between the bladder and the vagina—from a difficult, prolonged childbirth. Urine constantly dribbling through her vagina rendered her a pariah in her community. It was a complex, demanding operation, even in the U.S.—but in Haiti, with no resources?

Access to the internet was precarious, but Bengtson found a 15-minute window to download an article on the operation that the team studied. They hunted through closets full of materials other teams had brought down over the years for what they needed, including a suture so small you needed a microscope to see it. The next morning, after the six-hour operation, everyone was in tears. For the first time in 20 years, the ecstatic woman had woken up urine-free.

A LIFELINE TO HOPE

It took Lambert 16 years to complete the studying, training, and research to perform HIPEC surgeries solo. But even then, she struggled with self-doubts. After joining UMass in 2009 as a surgical oncologist specializing in peritoneal surface malignancies, she faced a steep surgical learning curve. Previously, there was always someone with gray hair and decades of experience across the table watching her work.

Doubt undermined her belief in her abilities. Surgery is a profession that keeps you humble. If you become overly self-confident, it will correct you. When post-op complications arose, Lambert took ownership of them. That’s the essence of being a surgeon. But each time there was a complication, she couldn’t help asking herself, “Am I helping people or just hurting them?”

In these early years of her career as a HIPEC surgeon, she first met Nate and Natalie at UMass on June 18, 2012, the day before his surgery. At 6'2", he towered over Lambert’s 5'2" muscular frame. Lambert gave them both a hug, then sat down. “This is my plan,” she said, laying out the surgery and recovery. Nate knew that Natalie wanted all the details, but she could feel him zoning out. As much as Lambert’s inclusiveness and humility moved her, Natalie felt the future was bleak. “This is hopeless,” she said.

“No, it’s not,” Lambert said. “We might not have cures all the time, but we get people years. My team is looking to give you time—to reset your timeline.”

As fellow members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Lambert had given Nate and Natalie’s number to the ward in Worcester. Relief Society members brought them food at the lodge they were staying at, which Lambert had also arranged free of charge. Even behind the scenes, Natalie thought, Lambert supported them.

After 12 hours and 20 minutes on her feet working on Nate, Lambert came out to talk to Natalie, cautioning her that the operation wasn’t a cure. “We couldn’t get it all, but we reset the clock.” For however long it took his cancer to grow, “He’s got that much time now.”

However, Lambert had encountered a complication that stemmed from the February emergency procedure. Nate’s bowel had been incorrectly resected and subsequently kinked, leading to a partial obstruction. She had corrected it, but in the days after the surgery, the bowels had ruptured and gone septic, requiring more surgeries before Nate could return to Utah. Once more, Lambert worried if a more experienced surgeon’s hands would have led to a different outcome.

A surgery on July 3 ran for three hours. Afterwards, Nate had to lie still on his back for a few days since the wound had been left open due to severe infection. Two days later, they took him back into the OR to clean out the abdominal cavity but still couldn’t close the wound. After three more days of Nate lying on his back, they were able to close the wound. He still had to spend another 10 days in the ICU. Lambert would visit him a few times every day and bring Natalie books. Nate didn’t want to talk about the procedures, so after her 12-hour days Lambert would talk about “life with Joe,” her husband of 20+ years, a competitive Olympic weightlifter and, like her, deeply passionate about serving others. Lambert also dedicated time to Natalie, going to church with her each Sunday for the duration of their stay. “Dr. Lambert” became Laura, and Laura became their friend.

A projected two-week stay ended up running six weeks before the Hardys said their goodbyes. They flew back to Salt Lake City, hoping the treatment and subsequent ongoing chemo would kill the cancer. As they drove home that evening through their neighborhood, the streets were lined with neighbors ringing cowbells, waving balloons, and shining flashlights. Being home with the children was the medicine Nate had craved, even if he lost 40 pounds and his kids called him Skeletor.

A year after Nate’s surgery, Lambert continued to struggle with doubts about her abilities. One dark winter morning, while out running, she thought, “If I get hit by a car and I couldn’t operate anymore, I’d be OK with that. At least I’d have a reason why I couldn’t do it and I wouldn’t just be quitting.”

Days later, she went on a cancer walk and talked to a mentor and former colleague. “I just can’t do this anymore,” she said.

“You do big surgeries on people who are sick, who have advanced cancers, who have had chemotherapy and radiation and who are malnourished,” he said. “You can’t expect things to go perfectly. There will be complications.” Don’t stop, he continued. “You’re a very good surgeon, and you take incredibly good care of your patients.”

She went back over her major complications that led to intubation and time in the ICU and discovered that the rate was 14 percent—well within the published literature’s guidelines. Most centers that provide HIPEC surgery see major complications in the 15 to 20 percent bracket.

Her mentor had been a lifeline to hope, she felt—not only for her but for the patients she was yet to treat.

ON THE FRONT LINE

Being a surgeon is about more than wielding a scalpel, Lambert knew. It’s also about relieving suffering. She detested walking away from a patient because surgery wasn’t an option. Due to a nationwide dearth of palliative care providers, UMass offered physicians already board-certified in other specialties the opportunity to be grandfathered in on palliative care with some training rather than a whole fellowship. While surgeons often view palliative care as giving up on a patient, Lambert jumped at the chance. When HIPEC was ruled out, with palliative care she could manage their pain and symptoms and help them transition to a different mode of care with different goals.

When she became board-certified in palliative medicine, she joined a then-small group of 40 surgeons nationwide who also provided palliative care. Lambert believed in embracing both palliative care and hospice since research showed that people could actually live longer if they turned to hospice at the right time. “When you stop poisoning them to kill their cancer, there's actually some reserve left so they can have time and quality [of life],” Lambert said.

Her interest in palliative care took her to a 2015 conference, where she first learned of existential-humanistic psychotherapy, which revolves around issues that cause existential distress. In California, she attended a course with 20 therapists on existential distress. She had never felt she needed therapy, and after a course leader asked attendees to ponder something they needed to work on, Lambert dismissed the request. However, as she thought it through, she reminded herself, “I’m dealing with death every day.” Suddenly she was in tears at the privileged place she occupied with her patients on the frontier of life and death.

Over the next few years, she read “Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death” by Irvin D. Yalom and grappled with the blocks people faced to a deeper engagement with mortality and loved ones. Those included fear of death, fear of meaninglessness, and fear of having your own agency or making choices where you lose opportunities. Most poignantly for so many relatives of patients she treated was the fear of being alone.

As she worked through and beyond her own existential crisis as a cancer surgeon, Lambert also identified a question she needed to ask herself: “How can I be present before so much loss and death?”

Years later, she brought a course for residents to both UMass and U of U Health’s School of Medicine called “The Healer’s Art,” which encouraged being present before someone else’s story. Even in the face of an incurable cancer, she argued, healing can be achieved through attentive listening by a physician.

A SHIFT OF TACK

Two years after Nate had his first HIPEC operation in 2012, Lambert and his Utah oncologist determined he could have a second one. He had done well enough with the chemotherapy; other than the tumor, which had grown back, he was healthy enough to manage the procedure’s debilitating impact. By then, Lambert was much more confident in who she was as a surgeon.

The second surgery began at 8 AM with both surgeon and family expecting it to be quicker than the previous surgery’s 12 hours. Mucin had spread to Hardy’s rectum, and Lambert had brought in liver and colorectal specialists to help out. Both surgeons battled mucin for two or three hours apiece. In total, the second operation lasted 18 hours. When Lambert came out around 3 am, she told Natalie, “I think we got everything.”

In the subsequent years, one unexpected obstacle Nate faced was local surgeons’ reluctance to perform small operations that he needed. They shied away from the post-HIPEC complexities of his anatomy, along with concerns of potentially encountering a cancer they did not understand.

What would happen if he needed a lifesaving, emergency operation, Natalie worried? Lambert told her they had to hope he could get on a plane fast enough to get to her in time.

Natalie felt intense relief in 2018, when Lambert and her husband moved to Utah after she accepted a position at U of U Health and Huntsman Cancer Institute as the Mountain West’s first dedicated HIPEC specialist. Lambert operated on Nate five more times in Utah. In the process, she had to make decisions about his care that led her to palliative surgery.

In 2019, Nate developed a tumor around his intestines that squeezed his bowels shut and threatened the blood supply to his stomach. Lambert referred him to a gastroenterologist at U of U Health for a placement of a stent to open up the bowel. The procedure was unsuccessful, however, and Nate and Natalie were warned that Nate would die soon because of the tumor. They told Lambert what had happened. She called back an hour later. “Get Nate up here right now.”

Once it was determined that the tumor attacking the intestine could not be removed, Lambert told them that HIPEC was no longer an option. As devastated as they were to lose the hope of more time, Nate refused to give up. “I’m not going anywhere,” he’d tell Natalie and Lambert, even though the mucin was attacking his lungs and his bones.

Lambert performed an emergency palliative operation to bypass the shut-off portion of the intestine so his bowels could work again, an operation most other surgeons would not have done.

“Nate’s kind of an enigma now,” Lambert told Natalie. “He just keeps going and surprising all of us.”

WORK-LIFE BALANCE

A natural educator, Lambert is passionately articulate about her subject while objective about its limitations. As director of the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine’s General Surgery Residency program, she has nevertheless found it hard in unanticipated ways.

For a surgeon who works 60-70 hours a week, guiding and mentoring a generation of residents more focused on work-life balance has led her to new terrain. “Sometimes, it can be hard to understand because I’ve never had a work-life balance,” Lambert says. “I have only ever worked.”

Today, she notices that students are far more excited about the technical aspects of surgery than meeting patients in clinic. For a doctor who values the physician-patient relationship, to Lambert that was unfortunate. The larger role of surgery as a practice is knowing when a patient needs it as opposed to when they don’t, Lambert says. Either way, a patient deserves to be taken care of after that decision has been made.

As program director, she must address the question of, “How do we continue to train excellent surgeons within the [legally mandated] 80-hour-working week for residents but also with their expectations of what they want out of life and their training?” If they work fewer hours, training will have to be extended to six or seven clinical years. “Who’s going to sign up for that?” she wonders.

At the same time, standards of surgery must be maintained. After medical school, where test-taking and classes are done online, residency is starkly different. To become a full-fledged surgeon invested in both skill set and patient is a transformative, demanding process. To Lambert, it’s akin to joining the Navy Seals, demanding immense levels of sacrifice and commitment.

Just like every industry and profession across the country, health care organizations will probably have to bend to the will of their future employees. But Lambert worries that quality of care for the patient will suffer with the push for work-life balance. “My personal belief is that the people who are going to be affected by it the most are the patients,” she says.

When Lambert looks back over her time with the Hardys, what she sees is the role she played not only as surgeon, friend, and support, but also quarterback—somebody to guide the team at all times so the patient and his family don’t have to explain the same agonizing story to one doctor after another.

“You need the continuity of somebody who’s been there with you through those big transitions,” Lambert says. “If surgeons just become technicians, simply there to fix problems and operate, we lose that human connection. If we don’t remind ourselves that the sacrifice and hard work is worthwhile because ‘I'm doing this to help a person,’ that approach causes burnout.” The antidote to burnout, she argues, “is not doing less. It is bringing your whole self and being present—being a human being interacting with another human being, not just an expert who fixes a problem.”

TIME TO GO

Nine and a half years on from Nate’s appendiceal cancer diagnosis, it had never occurred to either husband or wife that he would give up. Natalie had thought time and again that a miracle would help Nate get better. But that hope slowly died for her.

He developed chronic pain that was diagnosed as frozen shoulder but turned out to be caused by tumor-induced mobility issues. In Oregon to meet relatives, Nate’s pain worsened. On May 28, 2021, the man who for almost a decade said, “We're gonna keep going—I’m gonna keep going,’” uttered words Natalie thought she’d never hear: “I can’t do this anymore.”

By mid-September, it was clear that Nate was almost out of time. In the emergency clinic at Huntsman Cancer Institute on September 15, the couple learned that Nate’s lungs were filling up with fluid. Staff told him they needed to consider hospice.

“Yeah, we do,” Nate said.

“No, we don’t,” Natalie responded. It took her three days to accept it.

Lambert continued to be their advocate, kicking a medical student out of Nate’s room when he blithely asked, “Are we changing status yet?” about do not resuscitate (DNR) orders.

“You need to know your patient before you walk in,” Lambert told the student. “And what you said to them was really disrespectful. You didn’t read the room, and you had no compassion.” Here were Lambert’s core values at work, Natalie thought: “You take care of the body, but you also take care of the soul.”

Natalie also witnessed Lambert’s relationship with all her patients and realized it was as deep as the one she shared with the Hardys. “How can her heart be that big?” Natalie thought. “There must be so much room inside it.”

Perhaps that was on Nate’s mind the last time Lambert saw him at the hospital. Did he need anything, she asked as she was leaving?

“Look after Natalie,” he told her.

This would be the hardest part for both women. To watch Nate sink down even further until the end was one thing. But to help Natalie was the hardest part of the whole journey for Lambert—she couldn’t give Natalie the miracle she was hoping for.

After Nate returned home with hospice services, he talked to each of his children individually. Those conversations helped Natalie prepare for a new world of keeping her children’s hopes for their individual futures safe and attainable without their father.

The hope that had bonded the Hardys to medicine, to Lambert, and to a future together finally changed. It was no longer about Nate getting better or living longer. Now, it was about Nate not being in pain anymore.

Lambert came to see him and gave him a hug. “See you on the other side,” she told him.

In the living room, his children watched over him, along with his nephews, Natalie’s sister, and both sets of parents. In his last two days, he couldn’t talk and didn’t recognize anyone. Natalie had been prepared for the strange breathing, the fish lips, and the gasping that often came during the hours of death. But after a day of that, he relaxed, his eyes closed, and he looked more peaceful than she’d seen him in years.

On the eighth morning, the hospice nurse felt his vitals were so strong he might be with them a couple more days. The family talked among themselves, the children laughing as they put a puzzle together.

It was then that he ever so quietly snuck away. Nate Hardy died on September 29, 2021. He was 51 years old.

Natalie texted Lambert that Nate was gone. It stopped her cold. Somehow, she’d expected him to always be around. Later, Natalie told Lambert that he hadn’t gone the way she’d expected.

“Does that surprise you?” Lambert said. “He always surprised us. He never did things the way we thought he would.”

In April 2022, Natalie and Lambert went skiing together at Snowbasin—just as Nate and Lambert had so many times before. At one point, up on the mountain on one of those bluebird-sky, perfect-powder days, surveying the valley below them, they talked about why the Hardys had elected to go with Lambert, rather than other specialists with more hands-on experience.

“All we were looking for was some hope,” Natalie told her. “You were the first person to give it to us.”

The HEALER'S art

Story and concept by Stephen Dark

Design:

Sandy Kerman, Kerman Design

Photography:

Courtesy of the Hardy family

Courtesy of the Lambert family

Charlie Ehlert

Andrea Williamson

Co-Publishers:

Jesse Colby

Nick McGregor

Thank you to the staff of Huntsman Cancer Institute and the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine for their time, patience, and contributions to this story.