One writer's cautionary story about how his mother-in-law's stroke and fight to die on her own terms, taught him the importance–and limitations–of Advance Directives.

By Stephen Dark

April 7, 2021

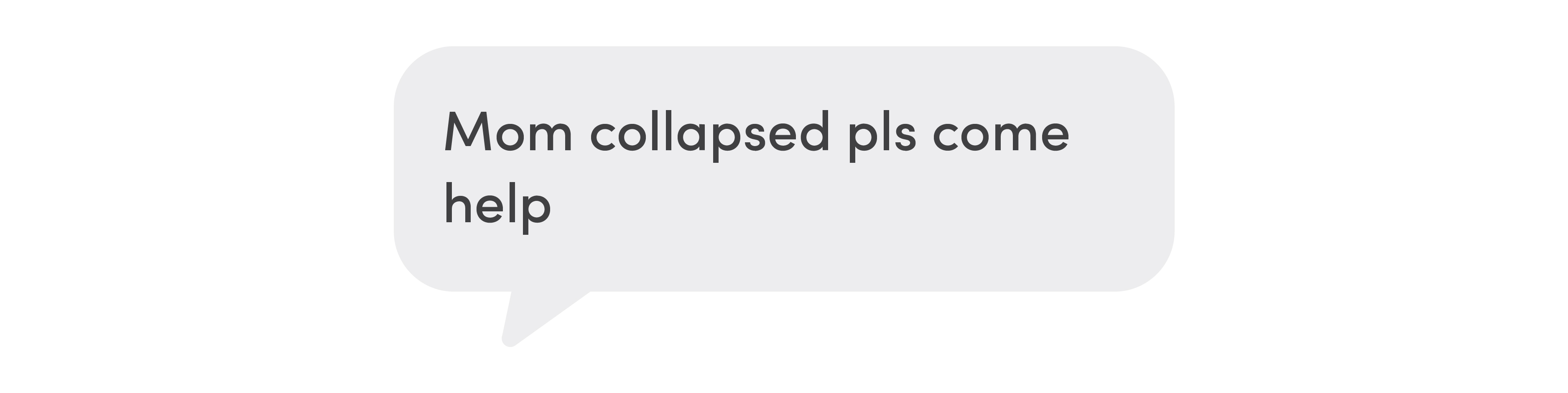

When I pulled into the parking lot at my downtown Salt Lake City office just after noon, my wife Patty Dark texted:

In the basement of our home that January 30, 2020, EMTs were trying to communicate with 95-year-old Mercedes Quijano, who was lying on the floor by her bed, half-covered by a duvet. She was not responding to their questions, her white, liver-spotted arms flailing in slow-motion distress.

On a gurney in the ER at University Hospital, Mercedes twisted and turned, her lips soundlessly moving. Doctors suspected a stroke.

Two years earlier, Mercedes had completed a Utah Advance Health Care Directive form with her geriatric health care specialist. The form provides a framework to state your health care wishes when a medical crisis leaves you incapacitated—just as had befallen Mercedes that day.

Mercedes had named Patty her “agent” to make decisions for her, myself as the alternate. As her medical proxy, we agreed that they would sedate her for a brain scan.

On the form, you can indicate if you want measures to keep you alive or if you don’t want to prolong your life. Mercedes had left those decisions to Patty, since she was more than familiar with her long-stated preferences regarding severe illness or being near death.

But an Advance Directive lacking a patient’s specific wishes beyond assigning a decision-maker fails to take into account the complexities that agent can face when an unexpected medical crisis propels their loved one into the arms of a hospital. Such an institution, by its nature, is dedicated to keeping people alive—at least until that is deemed no longer appropriate. On top of that, this collision between individual lives and medical care can occur in a time frame when seconds—not just minutes—count. Relatives find themselves under extraordinary pressure to make life-altering decisions for loved ones.

I am a writer for University of Utah Health’s public affairs department, and that week I was working on a story about “No One Dies Alone,” a local chapter of a national nonprofit that sends volunteers to accompany dying patients in their last hours. Now I was going on that journey personally, and I would learn a painful lesson: an Advance Directive is only as good as the conversations those involved have about how each loved one wants their end of life to be.

I made a decision my mother-in-law fought to overturn, leaving me struggling with regret in the days, weeks, and months after her stroke.

I asked licensed clinical social worker, Heather Smith, who was part of Mercedes’ palliative care team, if what I felt I had done to a woman I loved happened often?

“All the time,” she said. She described the Advance Directive as “an imperfect exchange of information” and pointed to the clause on the form that said the patient’s agent had sole discretion, which Mercedes had initialed. While she didn’t discourage choosing that option, she stressed the importance of making sure everyone involved went through every health care option listed on the form in detail. “Otherwise, your agent is going to feel guilty if they keep you going or if they don’t, because they didn't know what you would have wanted.”

But what else can you feel when you realize you’ve made a life-altering decision for a loved one they would not have chosen for themselves?

Moment of Truth

Saundra Shanti, one of three full-time chaplains at the 650-bed hospital, was summoned to the ER by a text: “Patient Mercedes Quijano. Christian support.”

Patty shared her disbelief with Shanti. Up until that day, Mercedes had been the picture of health. She’d had the problems that often plague you as you get older—high blood pressure and atrial fibrillation, for which she was on a blood thinner. But she walked every day and was remarkably fit for her age.

“Just yesterday, we were having a glass of wine with a friend of mine,” Patty told Shanti. “How did we go from there to here?”

What would Mercedes want, Shanti asked? Did she ever talk about a scenario like this?

Mercedes didn’t want to suffer, Patty said. Her mother had often talked about how both her grandparents, who raised her in a south Chilean port town, had died peacefully, her grandfather while playing cards and drinking whiskey with local priests, her grandmother while taking a nap. She never wanted anything to prolong life, Patty told her.

“She always brought up quality of life. She’d say, ‘If you can’t do anything for yourself, what’s the point?’”

Shanti felt it was clear: Mercedes wouldn’t want intervention.

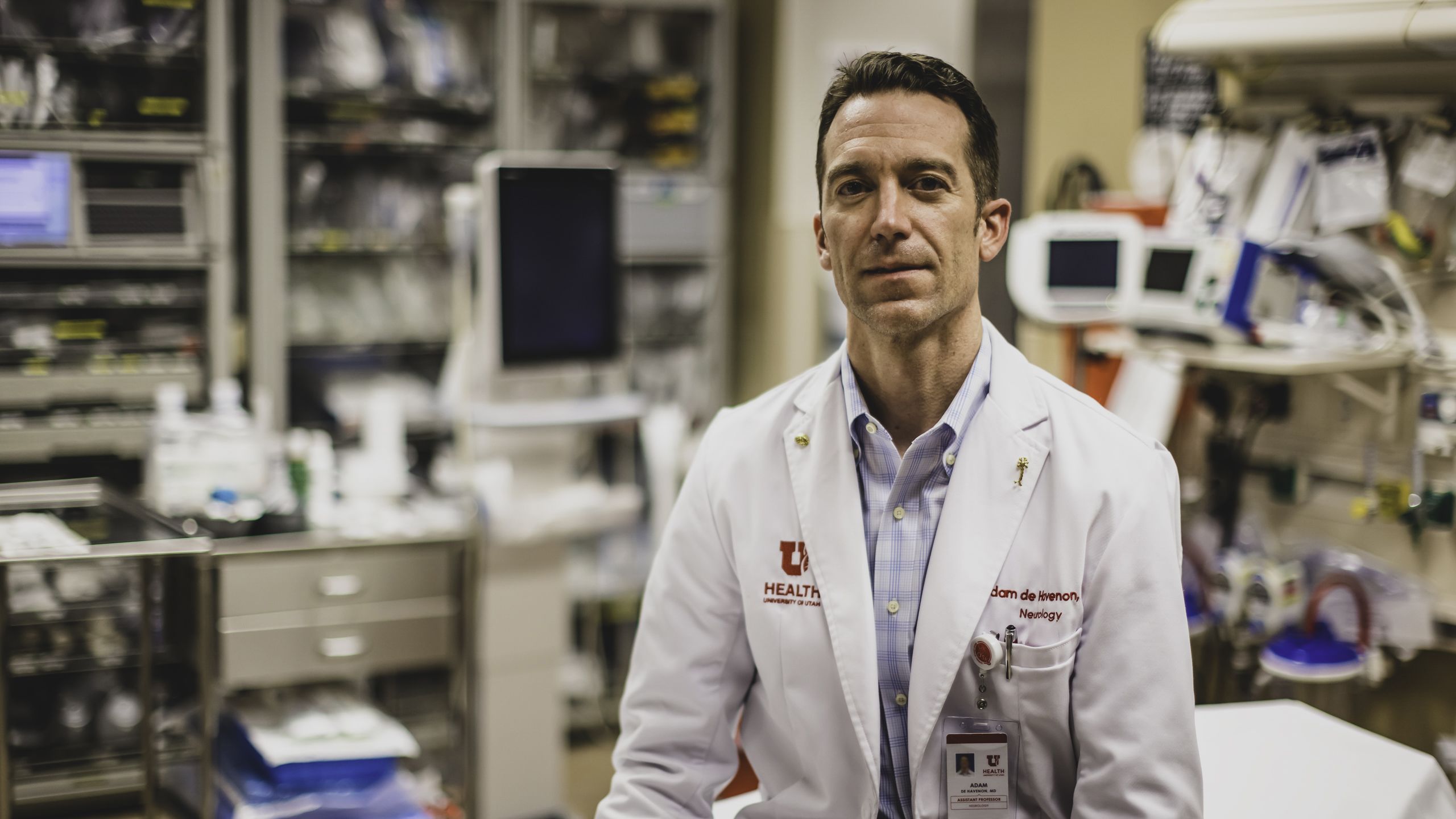

With the scans completed, Mercedes was wheeled back into the ER. The gentle, sympathetic gaze of Adam de Havenon, MD, a specialist in evaluating and treating acute strokes, held my eyes as he explained what they had learned.

Mercedes had suffered a massive stroke.

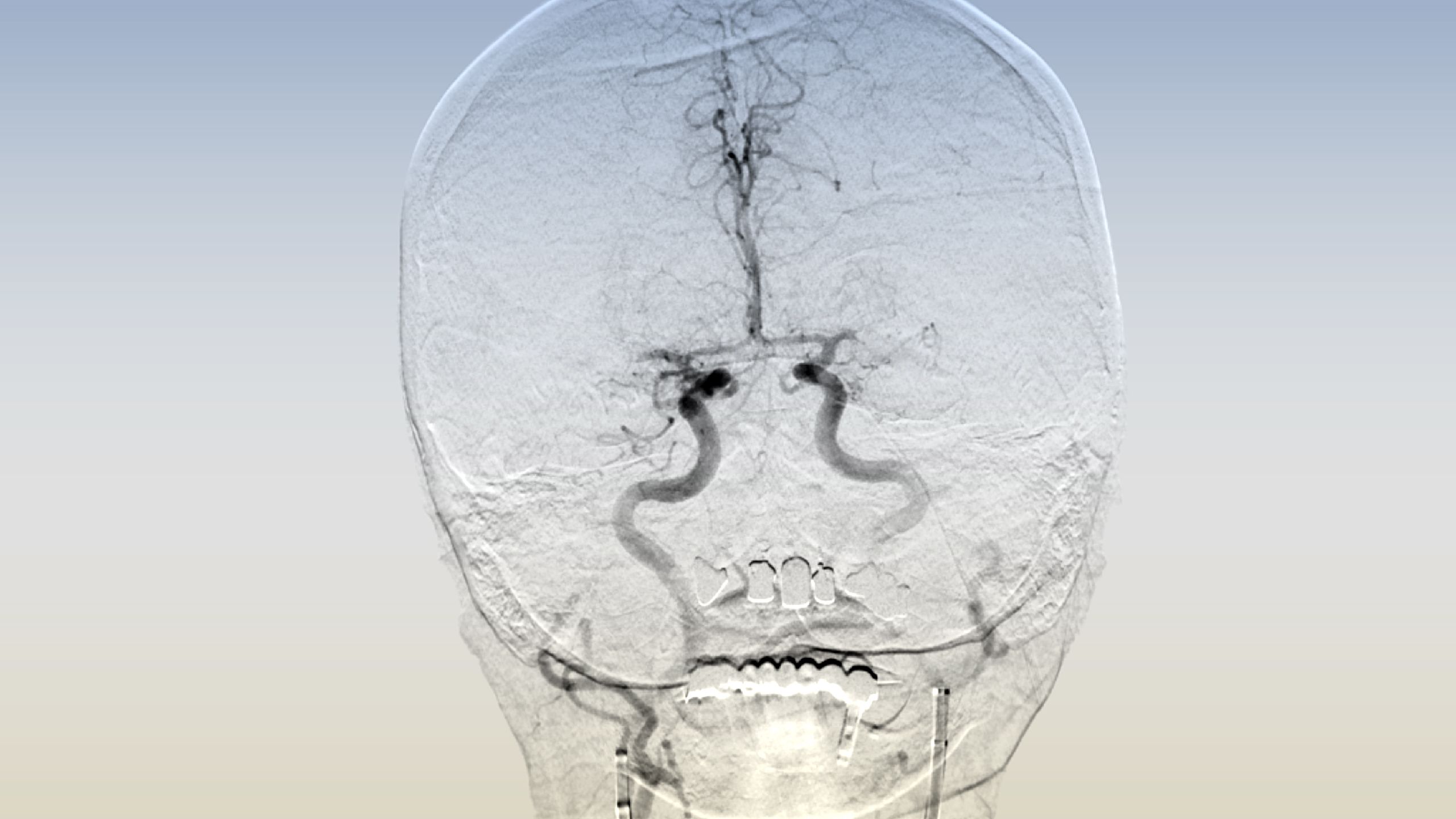

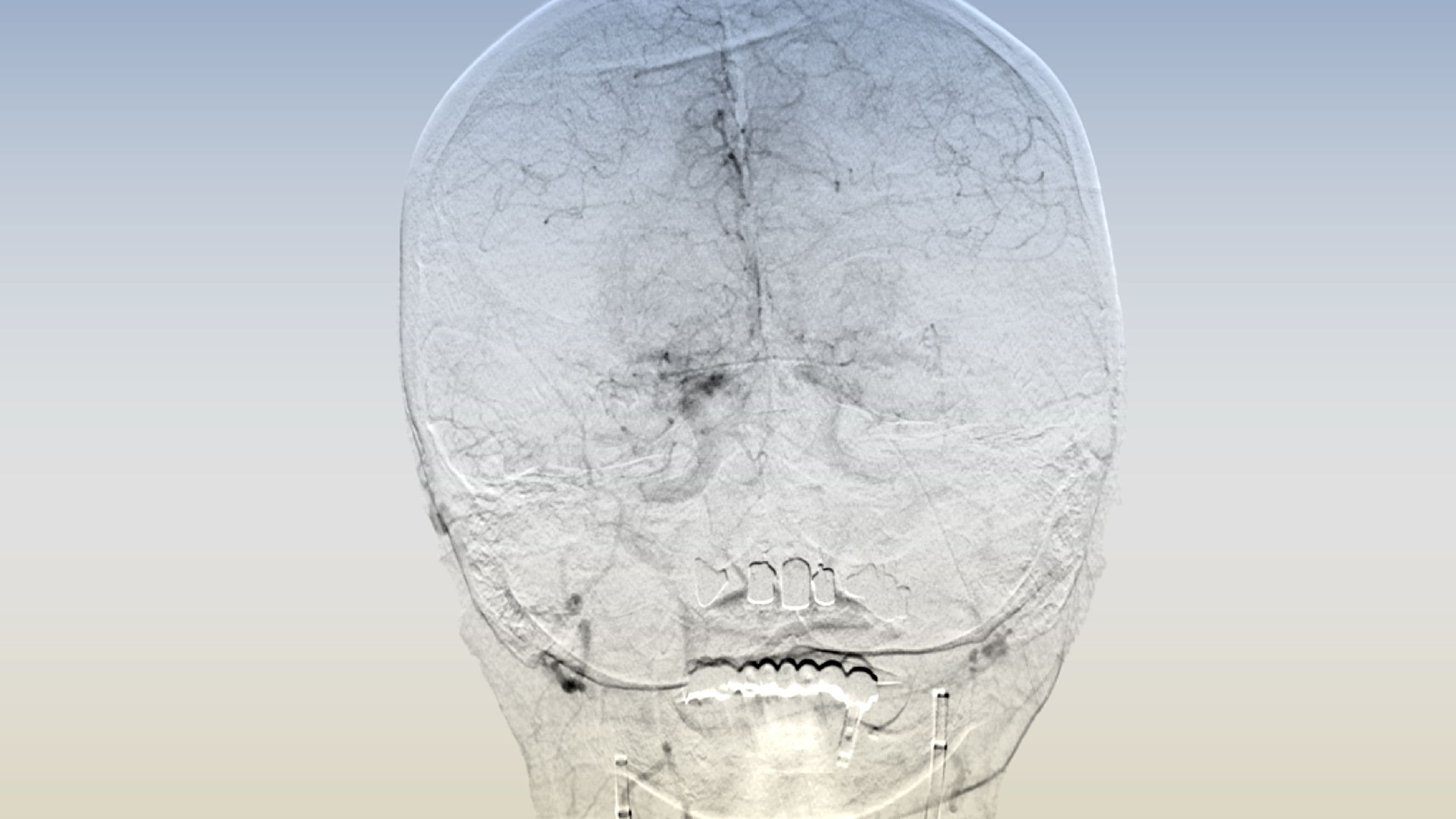

The culprits were two clots: silent, deadly mines that seemingly simultaneously had floated up major arteries on either side of the brain and blocked blood flow. Enough time had passed since the stroke that she was outside the window of the clot-busting medication, tPA. “Time is brain,” runs the stroke care mantra, and Mercedes’ brain was losing ground with each passing second.

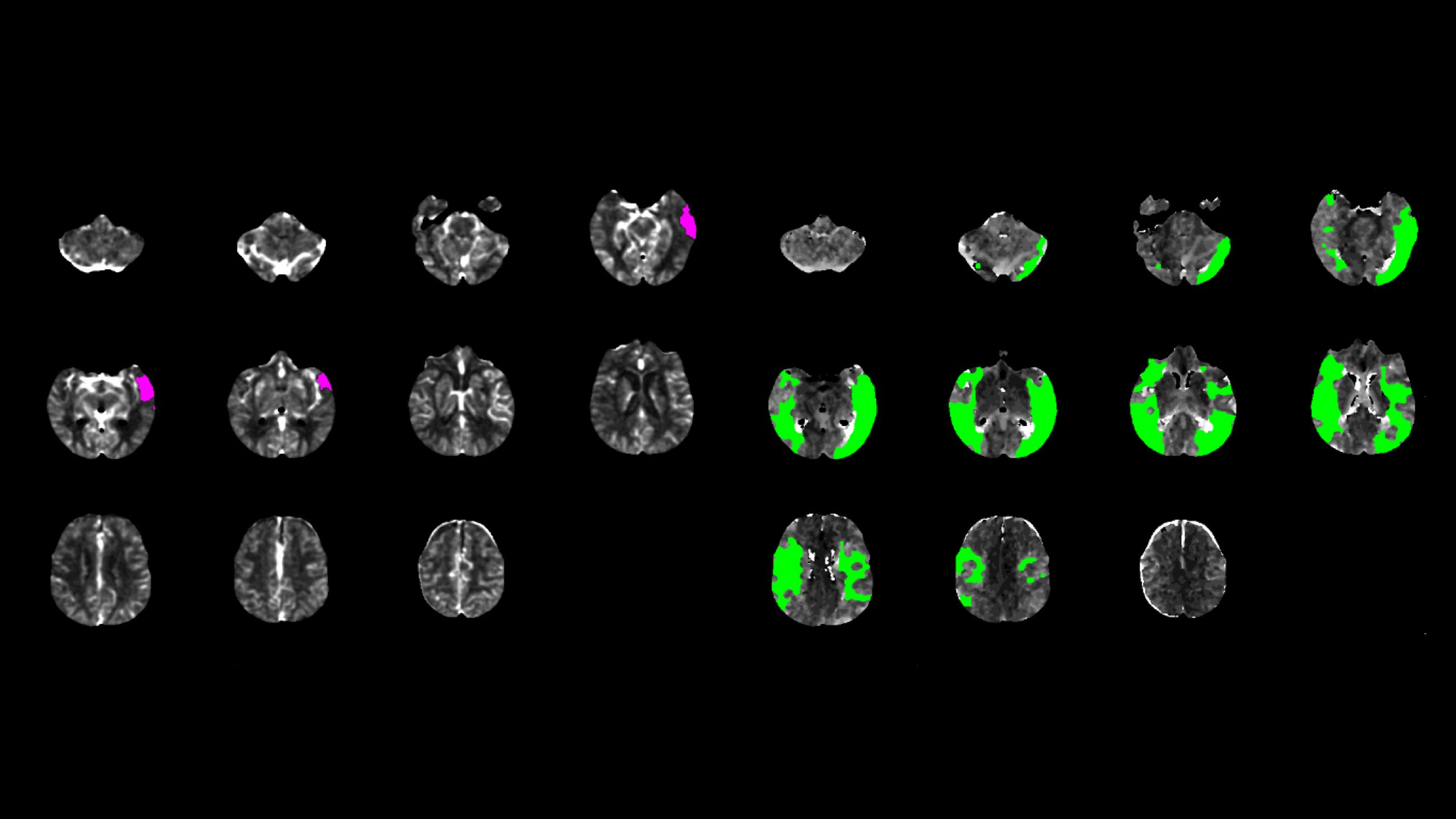

On his mobile phone, de Havenon showed me the eerily beautiful perfusion scan of Mercedes’ skull and the tiny, pink-colored island of brain killed off by the stroke, leaving green swaths of her brain at risk, but still possible to save.

She was a viable candidate for surgical intervention to remove the clots and restore blood flow to her brain, de Havenon said. Or, they could make her comfortable until she died. Several times he introduced the question, “Is this Mercedes’ time?”

They needed a decision, he said.

It was a simple question: life, of unknown quality or length, or death?

Slumped on a chair, Patty looked bewildered. She was trying to process events happening so fast she couldn’t think them through. Mercedes didn’t want any intervention, she knew that. Her mom would only want to live if she could be herself and not be a burden to others. The alternative, though, was pitifully bleak.

In the silence, I could feel Mercedes slipping from me and I held on hard.

“Yes,” I said to intervention, the word erupting from deep inside me.

Shanti was startled. I’d consented to something that contradicted what Patty told her. She was also concerned I hadn’t consulted Patty about the decision.

As they wheeled Mercedes out of the ER towards the Neurointerventional Suite, I stood hunch-shouldered where the gurney had been, the adrenaline rush from my decision already fading, the first seeds of doubt replacing it.

The Lady in the Black Hat

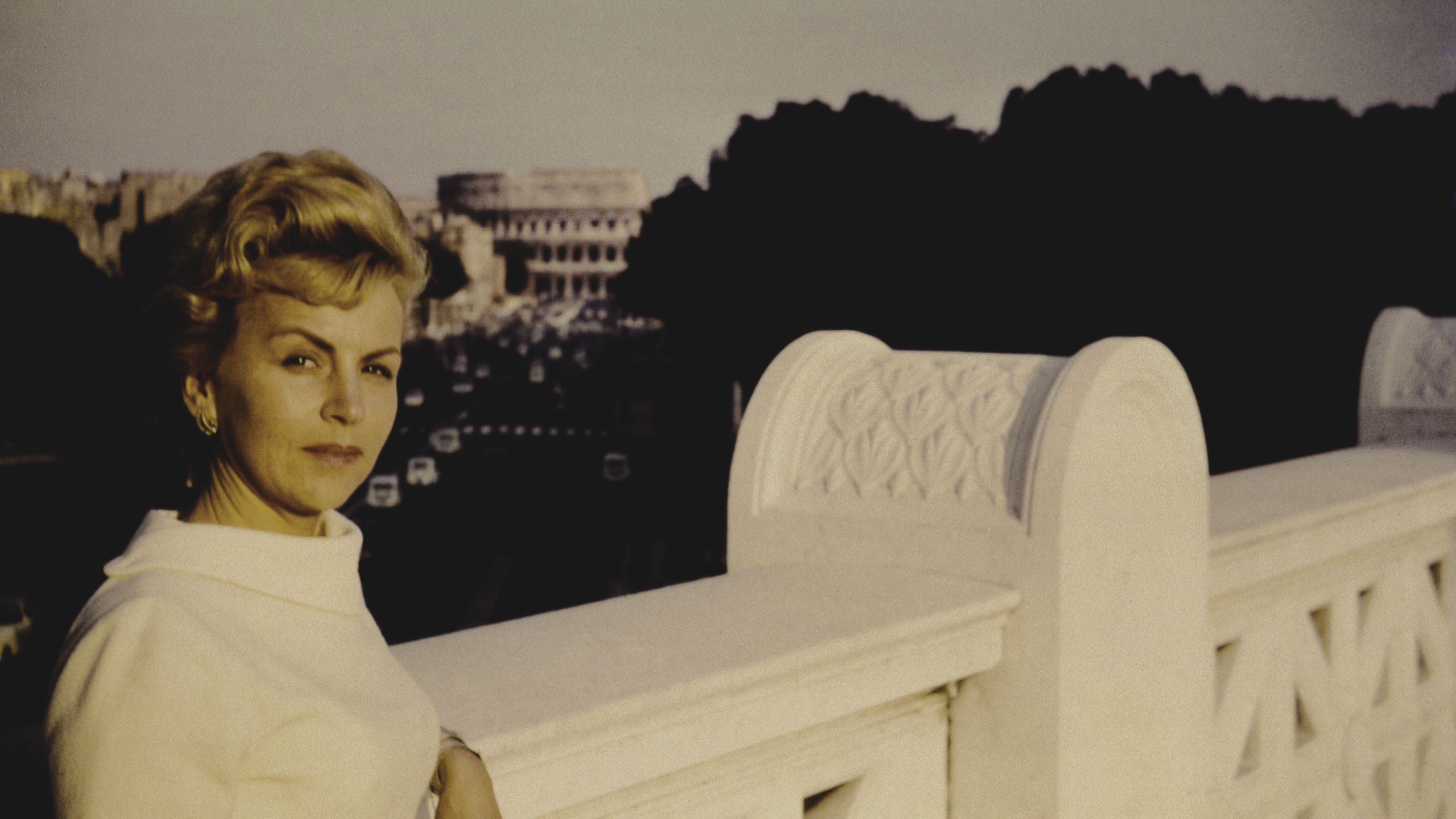

I wasn’t always the most gracious son-in-law, but I tried in my way. Three weeks before her stroke, I invited Mercedes out for tea at a local café. She talked about her childhood in the late 1920s, her face lit up not only by the morning light coming through the window behind her but also by her memories of riding her horse, Abaco, from her family’s lakeside home in Puerto Varas, Chile, down to the baker, her German shepherd, Sandor, in tow.

By the time she graduated from nursing school shortly after World War II, the Santiago, Chile-based hospital’s women’s ward where Mercedes worked was receiving severely ill patients who had traveled there from Germany by ship: Jews who clung to life after surviving a concentration camp, German women who had been raped. “They had no relatives, no family, no one to take them anything,” Mercedes recalled. So after her shift, she’d keep them company, bringing them pieces of fruit as gifts. But after four years in nursing, the nurse manager told her she was too emotionally attached to her patients and should find another profession.

After a spell in Argentina working as a seamstress and model, she moved to New York, where she had her own business hand-making dolls and translated at the United Nations.

Of all her stories, the image that stays with me is Mercedes dancing on a chair on top of a table in the early hours in a Harlem jazz club.

She married an Argentine career diplomat and polo player, Raul Quijano, in 1963. “He always carried a clean handkerchief and a rosary in his pocket,” Patty remembered about her father. Patty was born three years later.

Raul was briefly foreign minister for Juan Perón’s widow, President Isabel Perón, then Argentine ambassador to the U.S. during the Guerra de las Malvinas/Falklands War with Britain. Based in Washington, D.C., Mercedes managed the embassy staff but always on a frugal budget, making her own dresses for the myriad cocktail parties and dinner parties they gave.

She found the life of an ambassador’s wife repetitive, boring, and empty— even more so as her husband grew away from her.

After Raul divorced Mercedes, “Mom was left to pick up the pieces in D.C.,” Patty recalled. She started buying cheap properties, refurbishing them herself—she became an expert at dry-walling—and selling them. She would walk for hours and hours a day, working off her frustrations and stress. Walking, she’d say, “was the cure to all ills in my life.”

I met her in The Oak Room at The Plaza for drinks in 1987 when Patty and I were dating in New York. “She always loved you,” Patty said. “From day one, you were the son she never had.”

After we got married and lived in London, Mercedes followed us to Buenos Aires when we moved there in 1995. When we had two daughters, “she dedicated her life to helping raise them, taking them out for walks every day in the stroller,” Patty said.

A collapsed Argentine economy saw us leave Buenos Aires for Salt Lake City and a possible job for Patty. Mercedes eventually moved in with us when we bought a house in the elegant, tree-lined Salt Lake City neighborhood of 9th and 9th. Known in our neighborhood as “the lady in the black hat,” for the wide-brimmed blue-black hat she wore against the sun, she held court in local cafes with several Argentine friends she’d made, or read the local papers while Princeton, our Shih Tzu, dozed at her feet.

I thought she’d live forever.

Visit Date: 1/30/2020

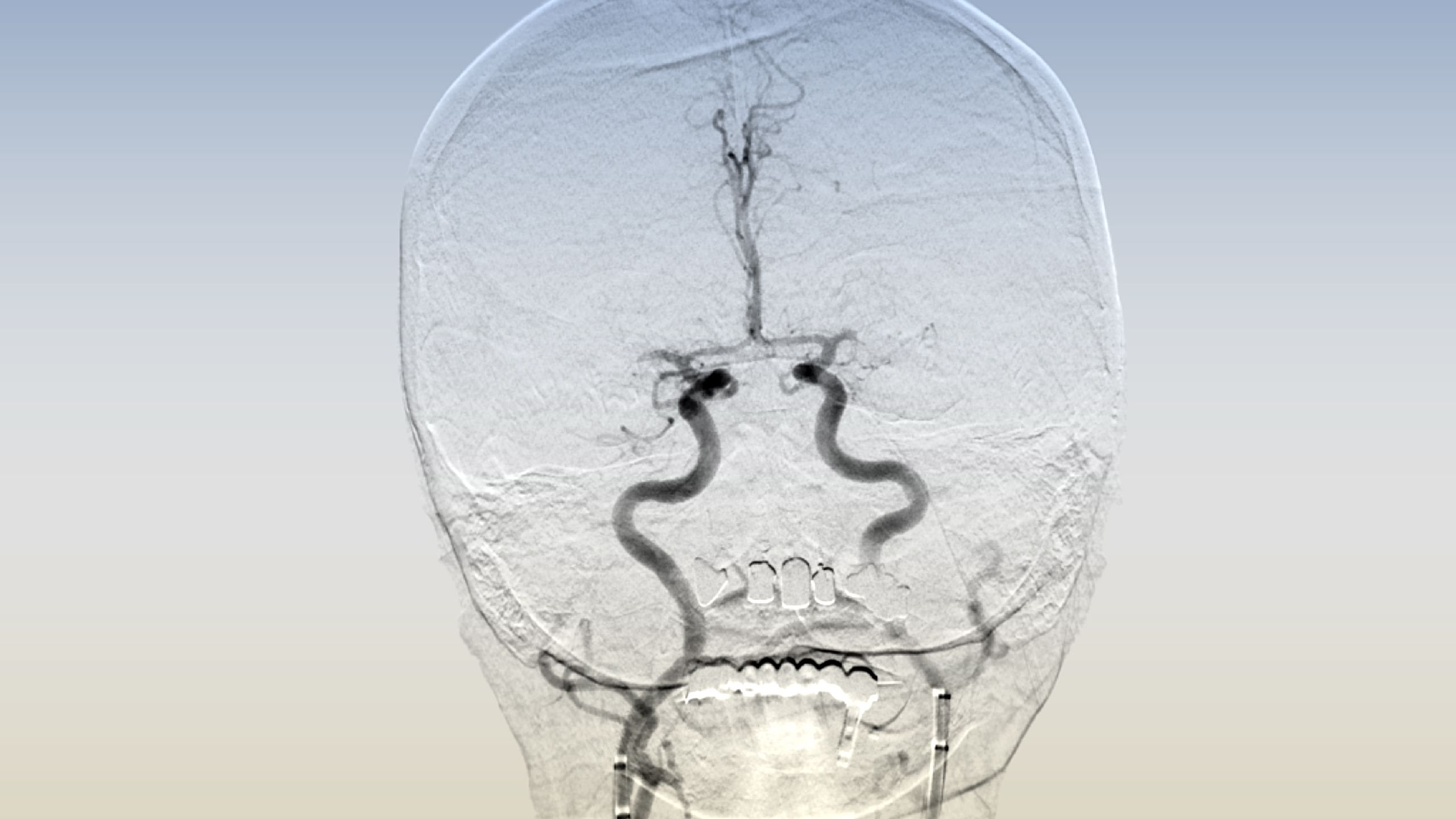

“Let me tell you, her case was crazy,” says Ramesh Grandhi, MD, the cerebrovascular neurosurgeon who operated on Mercedes. This type of stroke—bilateral mirror MCA M1 segment occlusions, to give its medical name—was one of the very few reported cases of its kind. “It’s the only time I have ever seen it,” he said. “I’m not sure I will ever see it again in my lifetime.” It wasn’t only that which made it stand out. There was the way her body had responded to the stroke, anterior arteries on either side of her brain re-routing her blood in a desperate attempt to keep her alive.

Grandhi saw in the almost perfect symmetry of the blockages a premonition of doom akin to the ghastly beauty of mushroom clouds rising from a nuclear explosion. Massive amounts of brain were not getting blood—the patient was going to die.

He opted to remove the clots simultaneously in a procedure called a thrombectomy. He showed images of catheters snaking up both her groin arteries, the clots being removed and blood flow restored. “Amazing, right?”

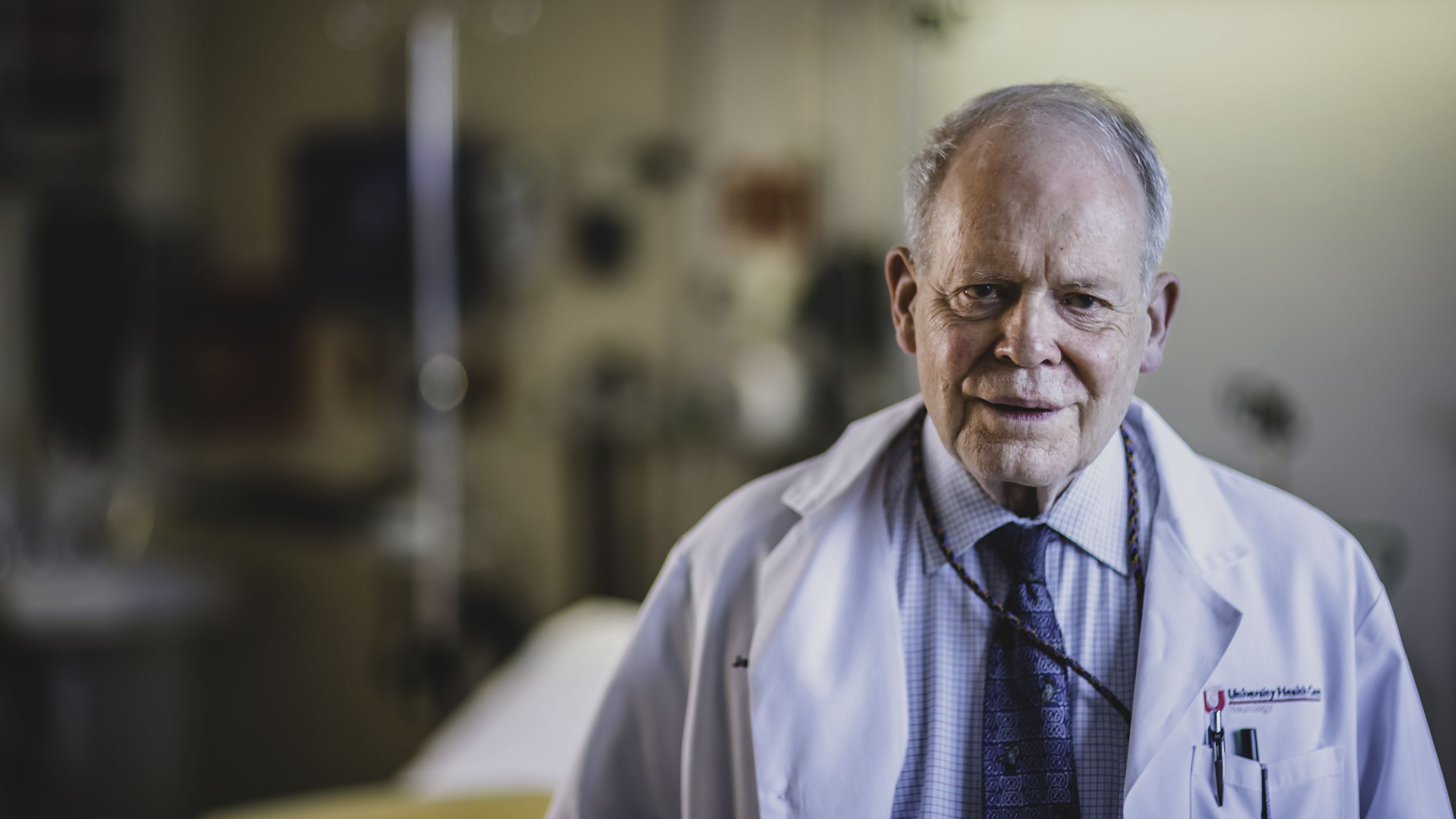

After surgery, Mercedes was transferred to the third floor Neuro Acute Care Unit, where professor of neurology and attending neurologist John Greenlee, MD, took over Mercedes’ health care.

Post-operative scans showed stroke-related injuries to both sides of her brain, information that hadn’t been accessible before the surgery. “It looked like fairly extensive damage,” Greenlee said.

In a sign of what was to come, as the night wore on, Mercedes became increasingly agitated. Staff put in a colostomy bag, but she persistently tried to pull it out.

By 7:30 pm, her mother’s behavior was upsetting Patty.

Visit Date: 1/31/2020

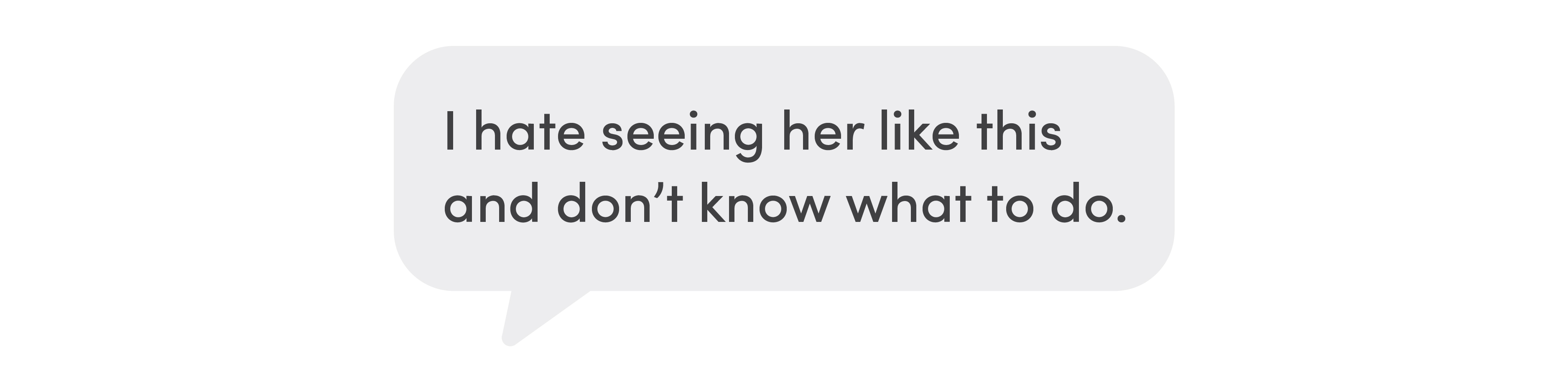

The next morning, Patty’s worry only escalated.

Patty met with Kristin Akers from the palliative care program. Patty told her about her mother’s life and how Mercedes had wanted a peaceful death. “We talked through our uncertainties about recovery, rehabilitation, and how much brain function she’d get back and whether ‘her aphasia (inability to communicate) will clear or not,’” Akers wrote in her notes.

When I spent time in the cramped ICU room, shuffling crab-like around equipment and therapists or nurses, there were still moments I was able to connect with Mercedes. At one point, I leaned over and smiled down into her eyes. She looked up into mine, so deeply, I felt myself fall into the waiting embrace of her love.

By 7 pm, she had calmed down, only a few hours later to start moving around in the bed. She tried to get up, pull off leads connecting her to monitors. By 9 pm, Patty felt her mother’s message to her was clear.

Visit Date: 2/1/2020

Patty was back at her mom’s bedside in the Neuro Acute Care Unit by 7 am.

That anger set Mercedes’ wishes and her post-operative medical care on a collision course. “There were major discrepancies between what the nurses were ordered to do and what the patient wanted,” Greenlee said.

Mercedes continued to resist treatment and had to be forcibly restrained, which only made her angrier. Five nurses held her down while trying to catheter her.

“No, please stop, OK? Please stop, enough,” Mercedes said. She fought with staff, shoving nurses aside, putting a foot over the side of the bed, repeating endlessly, “Excuse me, excuse me,” reminding Patty of how her mother would fight her way off a packed Manhattan subway train to get off at her stop.

Grandhi checked in on Mercedes. “Overall, we’re pretty psyched about how this looks,” he told Patty. Mercedes was able to look at him, and while she wasn’t able to verbalize, she seemed able to understand, he thought, indications of the vast amount of brain they had been able to save.

de Havenon was also encouraged. Mercedes’ post-operative scans, he felt, showed she would eventually be able to read, walk, even swallow. Admittedly, in those first days, weeks, and months, a stroke patient often didn’t resemble the person they had been before. But he was confident that would come.

When Greenlee conducted rounds that day, though, chaos and commotion came from Mercedes’ room.

She was fighting hand and foot, kicking at nurses, trying to leave. “Oh my god, what is wrong with you people?” she kept saying as they struggled to stop her from getting off the bed and pulling out the IV and catheter.

“Stop,” Greenlee told staff. “You don’t treat ladies like this.” While he knew that staff were only following providers’ orders, Mercedes was clearly expressing her fury at what was being done to her.

He took Patty aside. “What do you want to do?” he asked.

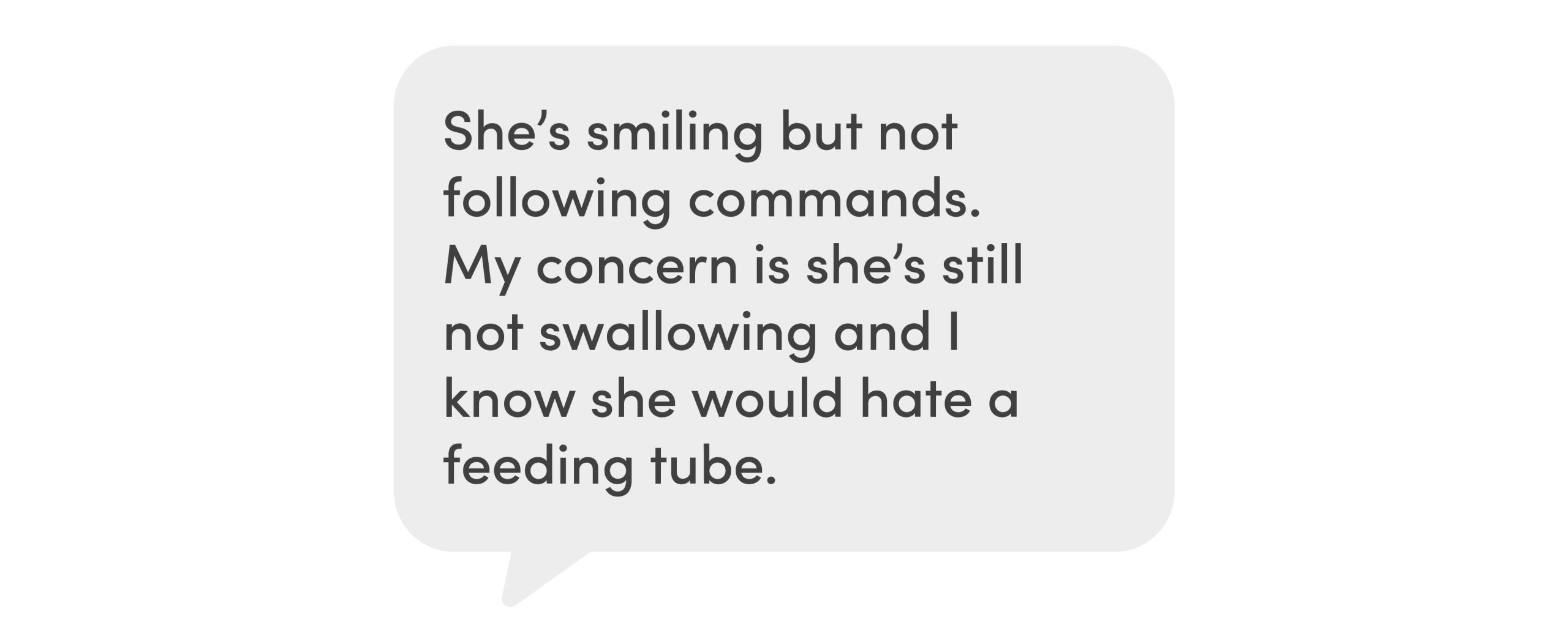

“She can’t swallow,” she said. “What kind of future is that?”

“People can be on a feeding tube for a long time, living comfortably in a home,” he said.

“If she couldn’t be independent, she wouldn’t want it,” she told him.

Greenlee laid out where Mercedes was heading. “The fact she can’t swallow and eat, and you don’t want a feeding tube ... it will end. Without sustenance, without water and food, she will die.”

I took over the bedside vigil that Saturday afternoon. Mercedes constantly remonstrated with the nurses as she tried to get up and they restrained her.

“Hey, hey, hey,” she said angrily.

Palliative care nurse practitioner Anna Freudenberg came in to see Mercedes at 5:30 pm. She was trying to take off her gown, pull off her leads, and stand up.

“She would never want this,” I told Freudenberg.

She got Mercedes washcloths to fold. Mercedes had always enjoyed ironing as a time for prayer and reflection. For a brief while it placated her. Seeing her folding cloths was like the most fragile sense of normalcy returning. It didn’t last long.

She put the cloths aside and once more tried to get out of bed. Through her rigid limbs and her straining muscles, I could feel Mercedes’ entrenched refusal to accept care.

Two members of Mercedes’ palliative care team: nurse practitioner Anna Freudenberg and licensed clinical social worker Heather Smith

“This was not how she wanted to be,” Greenlee said months later when I asked him about her case. Some people fight to stay alive—others cherish their independence and fight to the end, but not necessarily to stay alive. “It’s, ‘I want this over,’” he said.

“Patric-i-ah?” Mercedes asked. She was at home, I replied, and would be there tomorrow. “Nos vamos?” she asked. “Are we leaving?” I shook my head, unable to speak, and turned away.

Four nurses tried to hold her down once more, in part to secure her IV drip, which she had half-pulled out. She held on to my hand tightly, even as staff asked me to leave so they could re-secure her to the bed.

But even then, as I helped hold her down, she forced herself up on her elbows and kissed me. I stepped outside and wept under the bright hall lights.

Some of the nurses left and I went back in. She was tethered by two arms and a leg to railings, with boxing glove-like mittens on her fists, although she was already working one off. I comforted her, stroked her face, cupping her cheek and looking into her eyes. My back was breaking from constantly bending over as my tears soaked her mitten. The charge nurse briefly rubbed my shoulder in sympathy, which broke me a little more.

The next hours were grueling as I waited for when Mercedes was scheduled to receive her next shot of sedative, only to beg for a second one when the first failed to dent her agitation and struggling.

Finally, after a nurse had reached out to her provider, Mercedes received Haldol, used to treat psychiatric disorders. For a while, she pulled against the restraints and then slowly curled up on her side and drifted to sleep.

Visit Date: 2/2/2020

Patty was back at her bedside by 8 am. Mercedes had pulled her IV out during the night but was sleeping quietly when she got there.

Later, Patty met with Greenlee.

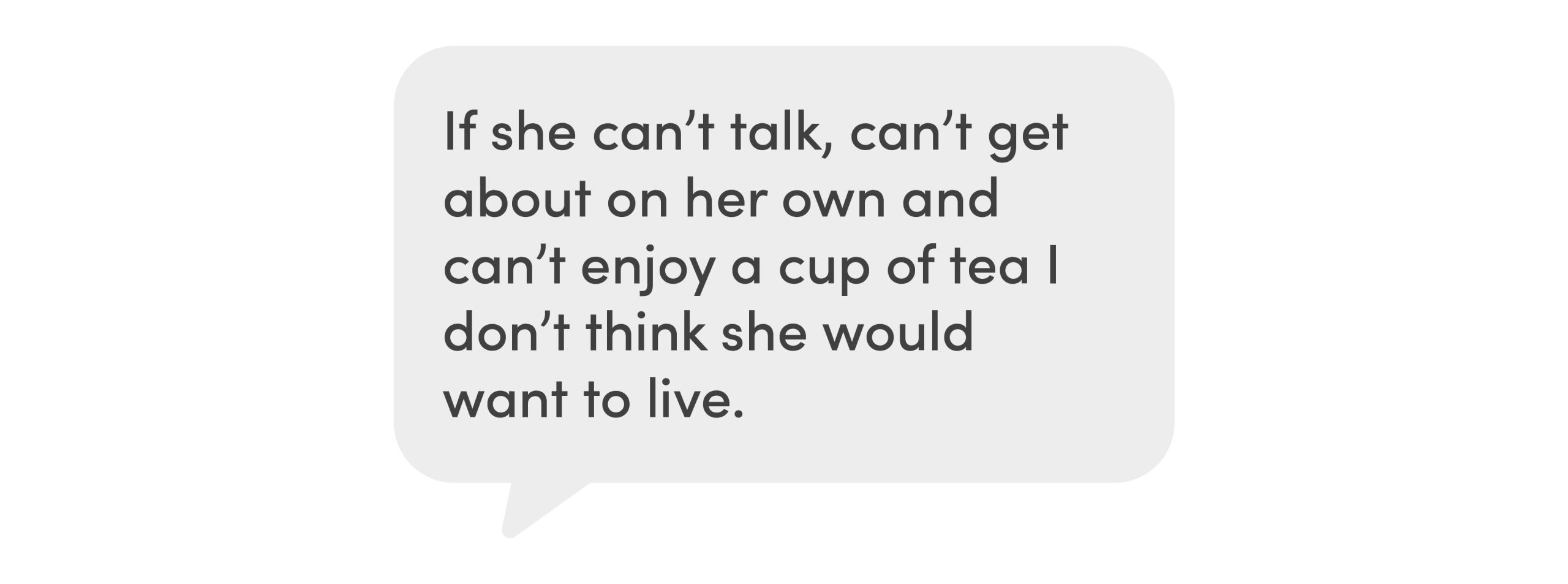

An hour before moving her to a hospice suite on the fourth floor, Patty texted:

The hospice room was starkly different from the ICU—no monitors, no drips, no medical technology. A glass-walled cabinet was opposite the bed, a different religious text on each shelf. There was a Bible, a Book of Mormon, a Quran, the Torah, all secured by a tiny gold lock.

Anna Freudenberg took over as attending provider for Mercedes as she transitioned to end of life.

She was no longer taking food or liquid, her body slowly shutting down.

That evening, a calm Mercedes spoke to her daughter for the last time.

“Night, night, I love you,” she said, smiling. Then she went to sleep.

Visit Date: 2/3/2020

Early Monday, a blizzard hit Salt Lake commuters, closing schools, businesses, streets, and the airport, which received a record 8.6 inches of snow. In the hospice suite, the view of the valley was whited out by the storm.

Our youngest, 18-year-old Katy, came with me to say goodbye that afternoon. As we passed the Moran Eye Center, our dog Princeton in her arms, tears trickled down her cheek.

Princeton stayed so still on Mercedes’ bed, as if he were afraid moving would hurt her, licking her cheek once as I went to pick him up.

In her last days, Mercedes hardly moved. She’d cough, a discrete, hollow sound, as if not wanting to disturb those gathered in her room.

Visit Date: 2/4/2020

When I covered her with her favorite blanket, a burgundy-red fleece, she didn’t stir. There were times when her breathing became quicker, less measured, tension lines above her upper lip. The hospice nurse increased her medication and she relaxed.

Tuesday evening, Patty and I left around 9 pm to get some sleep. I planned to return at 4 am, but there was no need. Just after midnight, Patty’s cell phone rang.

We got there in 15 minutes. Mercedes’ heart had stopped.

In the silence of her room, with no one watching, she had departed with the genteel dignity that was the hallmark of her life.

A young doctor came in around 12:45 am, moved his stethoscope around her chest, raised her eyelids, and flashed a light in tick-like motions. He offered his condolences and left.

“She got her wish,” Patty said.

Patty and I took our turns to kiss her goodbye. Her cheek was cold, the essence, the energy of life gone, her skin no longer responding to the touch of my lips.

Grief Will Out

Looking back, Greenlee saw Mercedes’ own authorship in her death.

“In a way, when she went, I thought that may have been her last declaration of independence,” he said.

“She made it as clear as she possibly could she did not want things done with her, and the implication is if things aren’t done with you, you are going to die. But I think really that was her decision.”

He admired Patty. “There was enough love and respect between her and Mercedes, your wife could intervene and guide things along.”

In March 2020, I interviewed chaplain Shanti at a table by the hospital cafeteria. I wanted to discuss my decision in the ER, which still ate at me.

I knew what I wanted to ask, but couldn’t get the words out. I typed, “Did I put her in a position where she had to force us to let her go?”, turned the computer around to show her, then doubled over in pain.

“She let you know, that was a gift,” she said. “She was telling them, ‘No, no, no,’ she was refusing their care. That’s when you shifted the plan.”

My pain surprised me. “Grief has its way,” Shanti said. “You either cooperate with it or it will take you. It comes out sideways.”

I wasn’t the only one that was hurt. Grandhi suffered, too. When he heard we’d shifted to comfort care three days after he operated, he was stunned.

In his opinion, we should have stayed the course with Mercedes and waited to see how she recovered.

“Yeah, it hurts,” Grandhi said. “It hurts from the standpoint of, well, why did I do this?” he said. “No one talks about how this affects us in our profession. No one does. It’s just another person lost that we touched. I physically touched her, I felt her blood.”

“Honor My Wishes”

To her Germanic bones, Mercedes was selfless, a kind, loving woman for whom being a burden to others was intolerable. “She was a person who always worked hard to please others,” Patty said. “She felt her job, her duty, was to ensure the happiness of others, not her own.”

And it was my job to respect her end-of-life wishes. In that, I failed. Intervention and its aftermath wasn’t what she wanted—she demanded that we let her go.

But what role had Mercedes’ Advance Directive played? It had identified Patty and I as her decision-makers, but nothing more.

Advance Directives that draw on a patient’s detailed wishes, Grandhi said, “help us understand to what point we push and where do we need to stop.” It’s important to ask, he continued, what is the base line? “What is the lowest common denominator of quality of life a person is OK with if something calamitous were to happen? Is being walker-bound acceptable the rest of your life? Are you OK living your life 80 percent rather than 100 percent?”

On Shanti’s Advance Directive, she has her daughter as her agent, her son as alternate, and two consultants—a social worker and a chaplain—to aid them when the time comes.

“Your only job is to do what I want,” Shanti told her daughter. “Honor my wishes.”

The Advance Directive is a prompt for what matters most—conversations between loved ones as to what they want to happen if a medical crisis were to befall them.

Shanti wants to relieve her daughter of any burden of not knowing if what she did was right. “I want to take the ambiguity off my daughter’s shoulders,” she said. “I want her to be able to say, ‘I did the right thing.’”

I will never be able to say, “I did the right thing,” but when we scattered Mercedes' ashes, something settled inside me.

Mercedes loved water. One of her happiest moments in her last years was sailing off the Florida coast with Patty’s cousin and her husband.

A photo immortalizes her relaxed smile and posture as she guides the tiller, taking the boat to sea.

Out of respect for her love of the sea, at Christmas we went to Florida and sailed out on that same boat one afternoon with our daughters, Elli and Katy.

Patty leaned over the stern and tipped over the bag containing her cremated remains. At first, the ashes were no more than a bilious mushroom of dust in the water, only then to unfurl, unwind, and straighten as a current caught them and gave them back a bodily dimension, undulating, rippling, flowing on, a mermaid answering the siren call to return home.

Mercedes Quijano

1924-2020

“Night, night, I love you”

The End of Her Days

Thank you to each and every member of the team who cared for Mercedes during her time at the hospital.

Story by Stephen Dark

Design by Jessica Cagle

Staff Portraits by Charlie Ehlert

Family Images provided by Patricia Dark