State of Suffering: Curbing the Rise of Utah Suicides

November 4, 2022

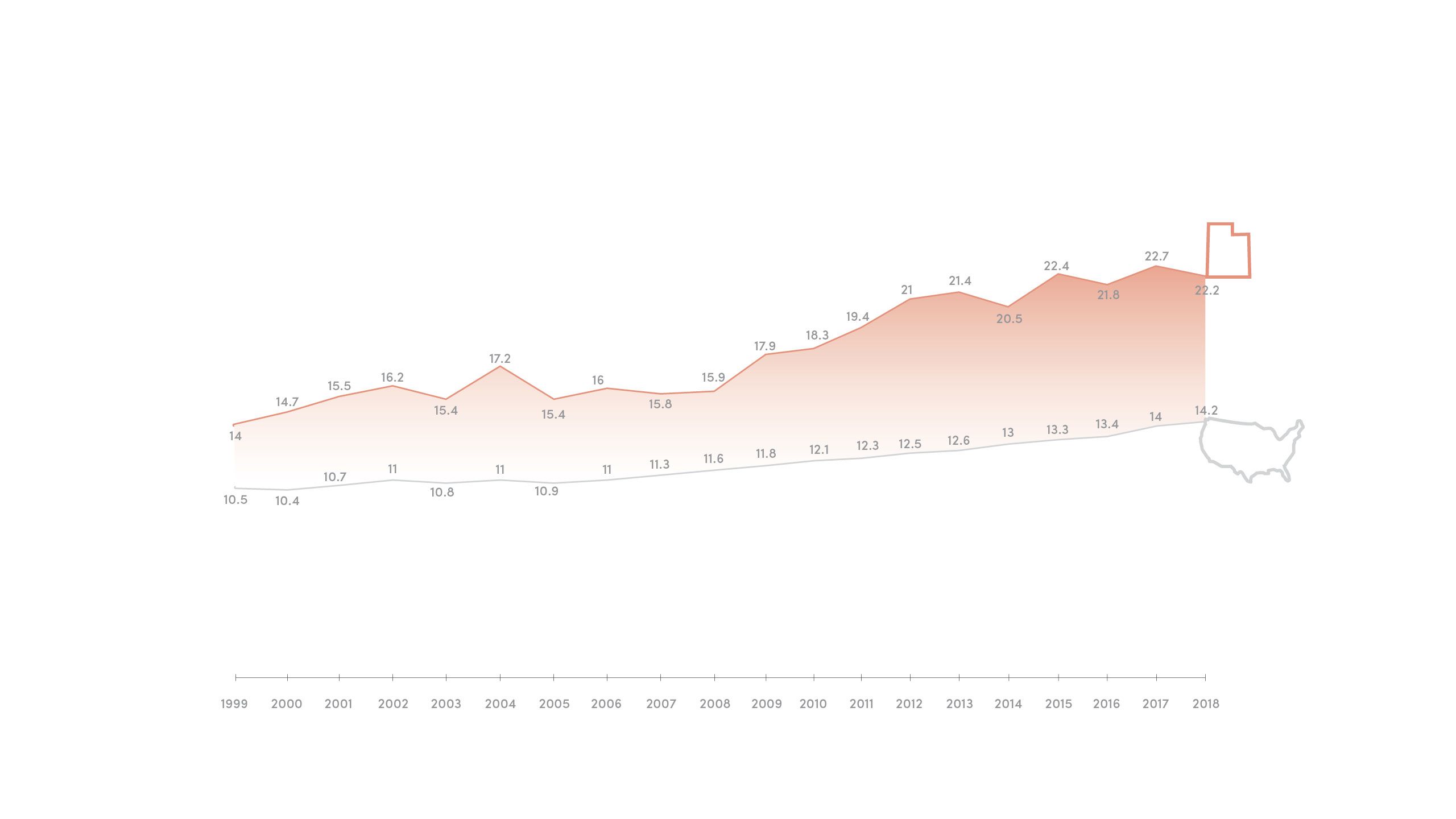

Utah's suicide rate (per 100,000) is nearly double the national rate. That’s a sobering statistic. What’s worse, suicide is the leading cause of death among one of Utah’s youngest groups: teens aged 15-19. In the face of climbing Utah suicides, can we save a suffering state? Can we afford not to?

As a child, loneliness dogged Julia Ludlow like an unwanted shadow. After years of struggling to make friends, she had resigned herself to a life of solitude: quiet rides home on the school bus and nights cooped up in her bedroom, hermit-like, with no one to talk to.

Despite book smarts and a gentle demeanor, Julia struggled to connect. She felt invisible, suffocating under the isolation, until one fall day like any other in 2015, when she packed a dusty Altoid mint tin with as many Tylenol pills as she could fit. Later that afternoon, she would retreat into a quiet alcove near her school cafeteria in northern Utah and attempt to end her life. She was 13.

Luckily, fate intervened. While collecting water to wash down the rest of her pills, Julia ran into a classmate and shared her secret in between sobs. Something broke inside of her, and she agreed to meet with the school counselor and complete a mental evaluation form. “When I checked the box that said I wanted to kill myself, the fear on my parents’ faces was something I’ve never seen before,” she says.

While Julia felt utterly alone, there are many more like her. An unrelenting stigma and limited access to mental health care has been linked to a disturbing rise in suicides across the state, with some victims as young as nine.

There’s Lilith Shlosman, who first attempted suicide as a freshman due to bullying and other factors. In January 2013, 12-year-old Dylan Aranda died of suicide. By December, 30 other teens would do the same.

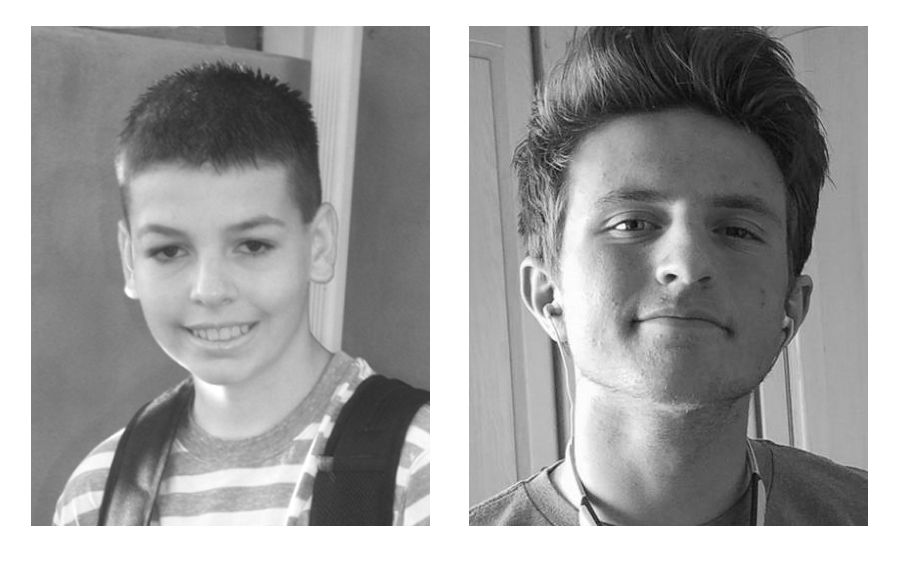

Dylan Aranda (left) and Chandler Voutaz (right). Photos provided by parents

Dylan Aranda (left) and Chandler Voutaz (right). Photos provided by parents

In 2017, Herriman High School student Chandler Voutaz died by suicide using a firearm. (Firearms are involved in about half of all teen suicide deaths.) Less than a year later, six more students from Chandler’s school had joined him.

As a child, loneliness dogged Julia Ludlow like an unwanted shadow. After years of struggling to make friends, she had resigned herself to a life of solitude: quiet rides home on the school bus and nights cooped up in her bedroom, hermit-like, with no one to talk to.

Despite book smarts and a gentle demeanor, Julia struggled to connect. She felt invisible, suffocating under the isolation, until one fall day like any other in 2015, when she packed a dusty Altoid mint tin with as many Tylenol pills as she could fit. Later that afternoon, she would retreat into a quiet alcove near her school cafeteria in northern Utah and attempt to end her life. She was 13.

Luckily, fate intervened. While collecting water to wash down the rest of her pills, Julia ran into a classmate and shared her secret in between sobs. Something broke inside of her, and she agreed to meet with the school counselor and complete a mental evaluation form. “When I checked the box that said I wanted to kill myself, the fear on my parents’ faces was something I’ve never seen before,” she says.

Julia Ludlow stands near her family home in northern Utah. Photo by Jen Pilgreen

Julia Ludlow stands near her family home in northern Utah. Photo by Jen Pilgreen

While Julia felt utterly alone, there are many more like her. An unrelenting stigma and limited access to mental health care has been linked to a disturbing rise in suicides across the state, with some victims as young as nine.

There’s Lilith Shlosman, who first attempted suicide as a freshman due to bullying and other factors. In January 2013, 12-year-old Dylan Aranda died of suicide. By December, 30 other teens would do the same.

Dylan Aranda (left) and Chandler Voutaz (right). Photos provided by parents.

Dylan Aranda (left) and Chandler Voutaz (right). Photos provided by parents.

In 2017, Herriman High School student Chandler Voutaz died by suicide using a firearm. (Firearms are involved in about half of all teen suicide deaths.) Less than a year later, six more students from Chandler’s school had joined him.

More Utah teens die from suicide than the four other leading causes of death—poisoning, car accidents, homicide, and other injuries—combined. Because of this, Utah and a stretch of surrounding states in the Mountain West have been aptly named the “suicide belt.”

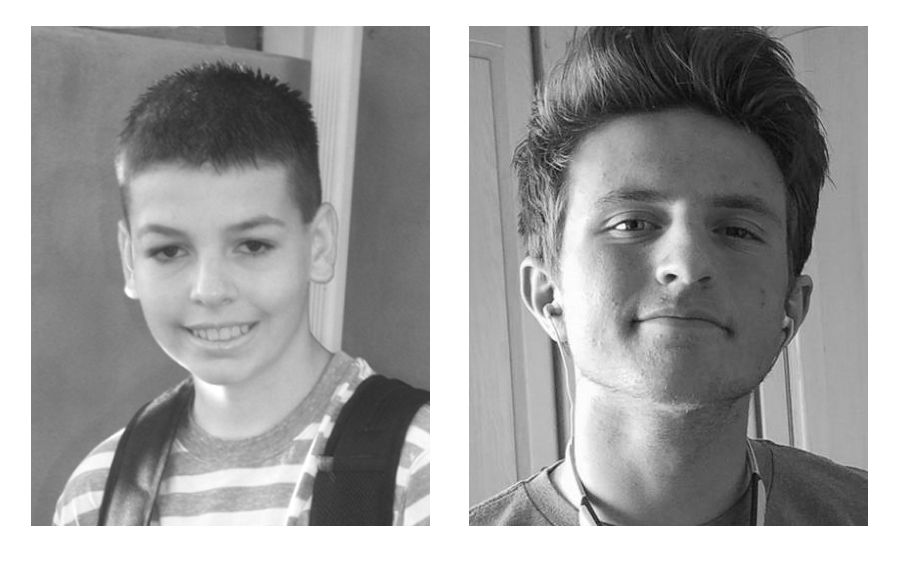

The "suicide belt" refers to a collection of states in the Mountain West with elevated suicide rates. (As you move your cursor across the map, you'll see individual suicide rates.)

While youth suicides have slowly risen across the nation, Utah’s rate has soared. In 2015, the nation’s average teen suicide rate stood at 4.2 per 100,000. That same year, Utah’s stood at a horrifying 11.1. In the last two decades alone, the state’s youth suicide rate has tripled.

*Sources to all data points and statistics referenced within this story can be found here.

More Utah teens die from suicide than the four other leading causes of death—poisoning, car accidents, homicide, and other injuries—combined. Because of this, Utah and a stretch of surrounding states in the Mountain West have been aptly named the “suicide belt.”

The "suicide belt" refers to a collection of states—Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico—with elevated suicide rates.

The "suicide belt" refers to a collection of states—Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico—with elevated suicide rates.

While youth suicides have slowly risen across the nation, Utah’s rate has soared. In 2015, the nation’s average teen suicide rate stood at 4.2 per 100,000. That same year, Utah’s stood at a horrifying 11.1. In the last two decades alone, the state’s youth suicide rate has tripled.

*Sources to all data points and statistics referenced within this story can be found here.

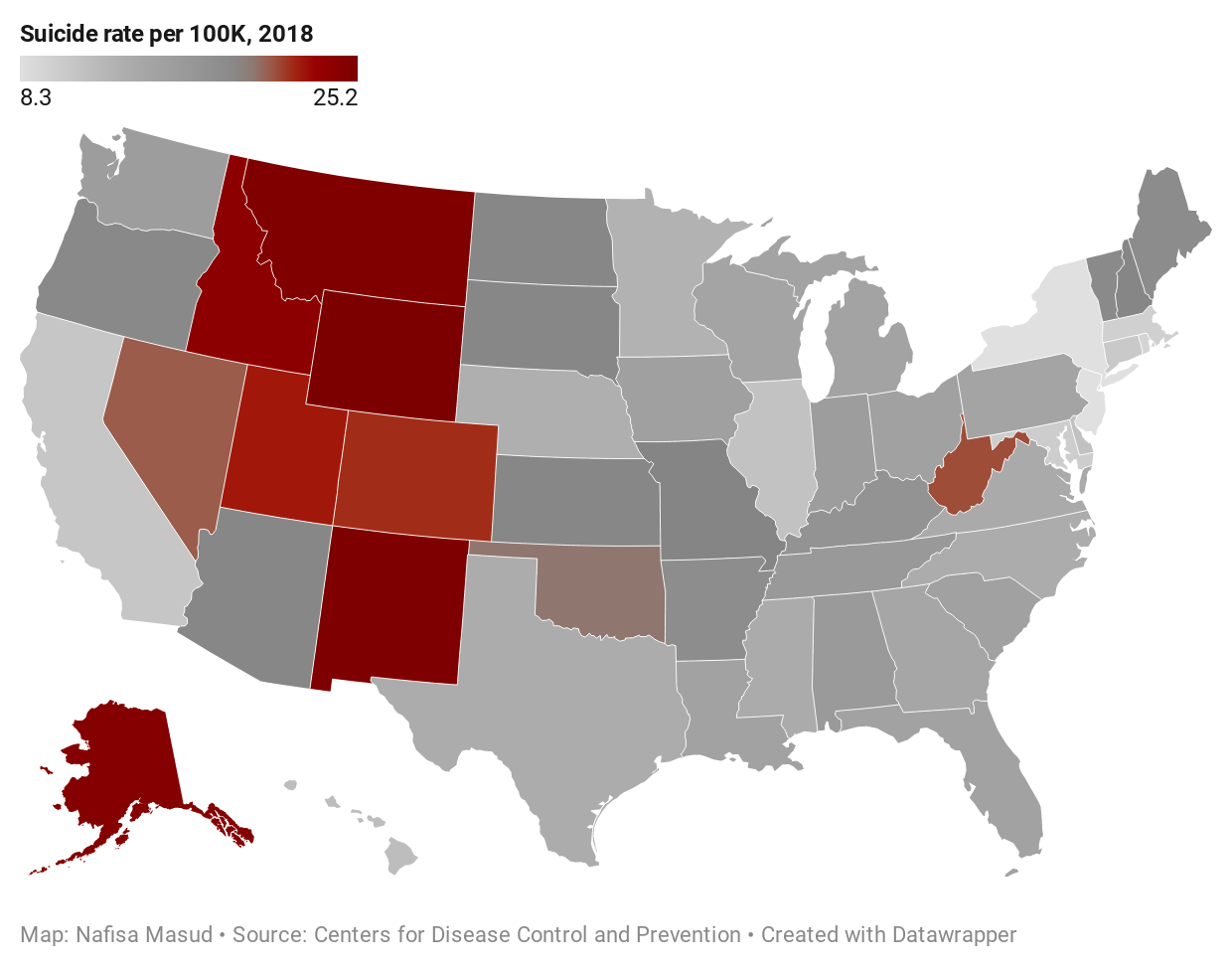

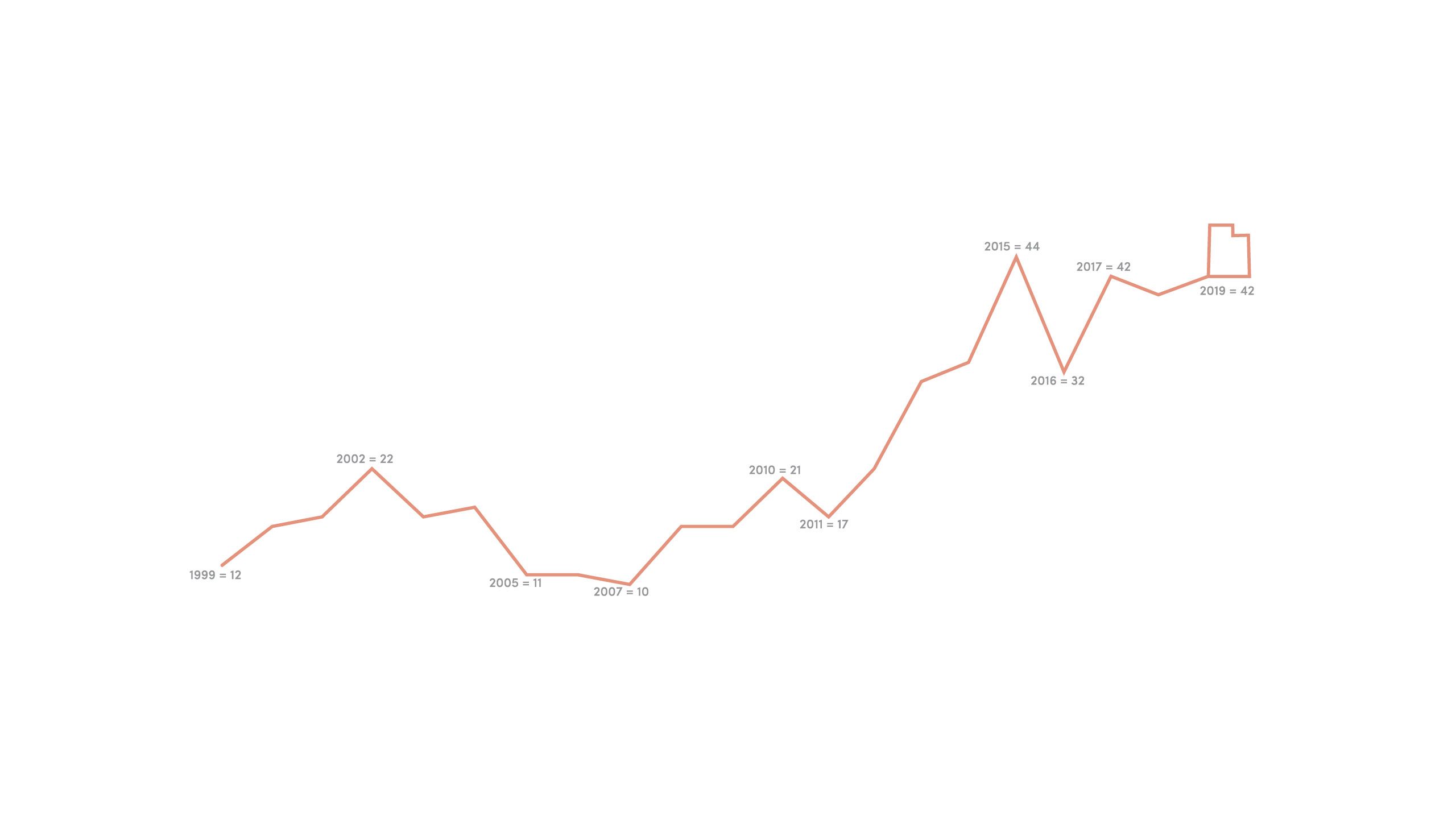

UTAH TEEN SUICIDES PER YEAR

In 1999, 12 Utah teens committed suicide. By 2019, that number more than tripled to 42. A consistent upward spike, alongside some small dips, throughout this time period are marked along this line. (Label: year = number of suicides.)

When Julia attempted suicide in 2015, she was one of more than 4,500 Utahns who tried to take their lives—one of the highest years on record. This line graph of Utah teen suicides, and that of the overall Utah suicide rate below, experienced similar spikes in 2015.

UTAH YOUTH SUICIDES

Suicide is the

#1

cause of death

for Utahns aged 10-17

Utah children

as young as

9

years old

have expressed thoughts of

depression and suicide

Utah’s youth suicide

rate has more than

tripled

in the last two decades alone

IT'S NOT ONLY TEENS, THOUGH

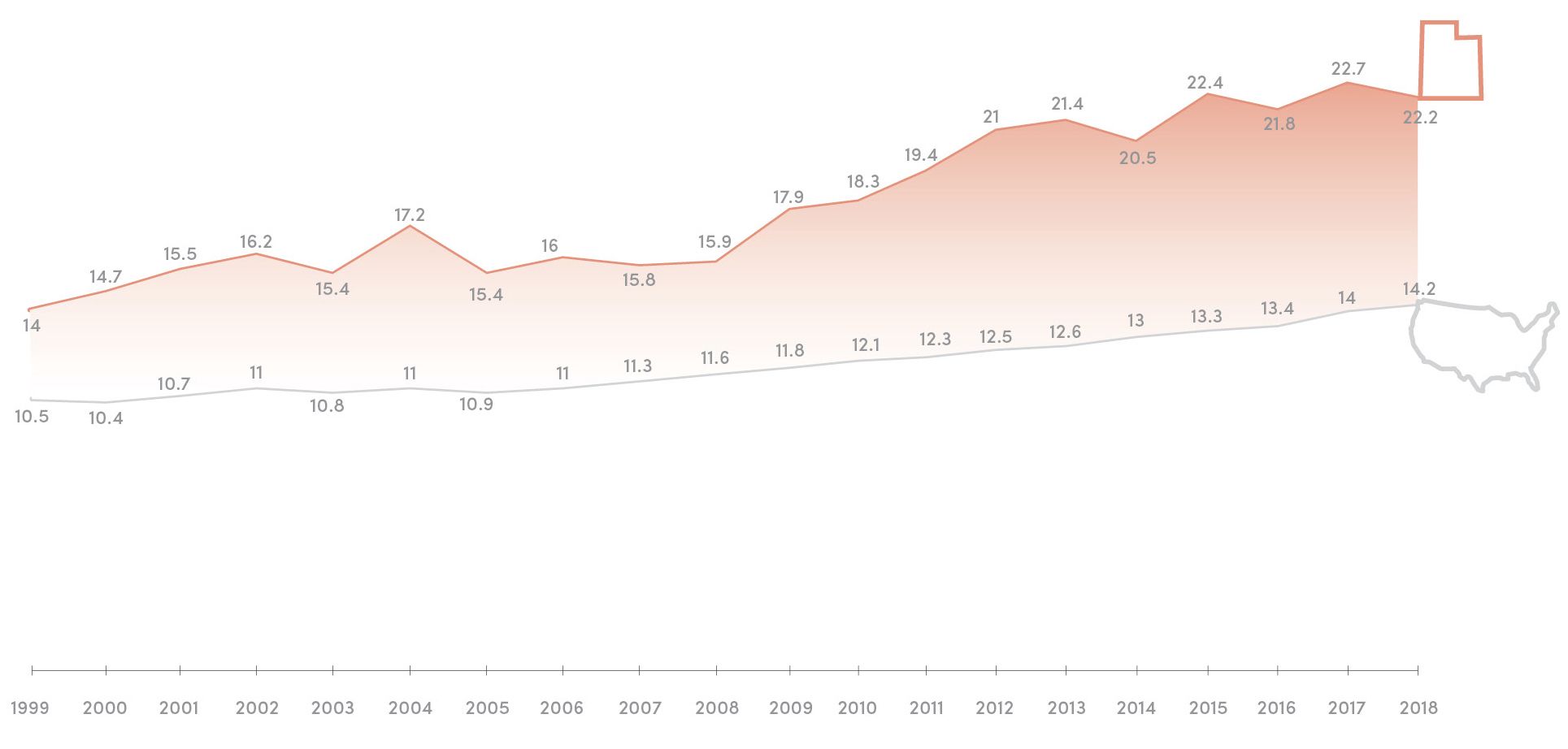

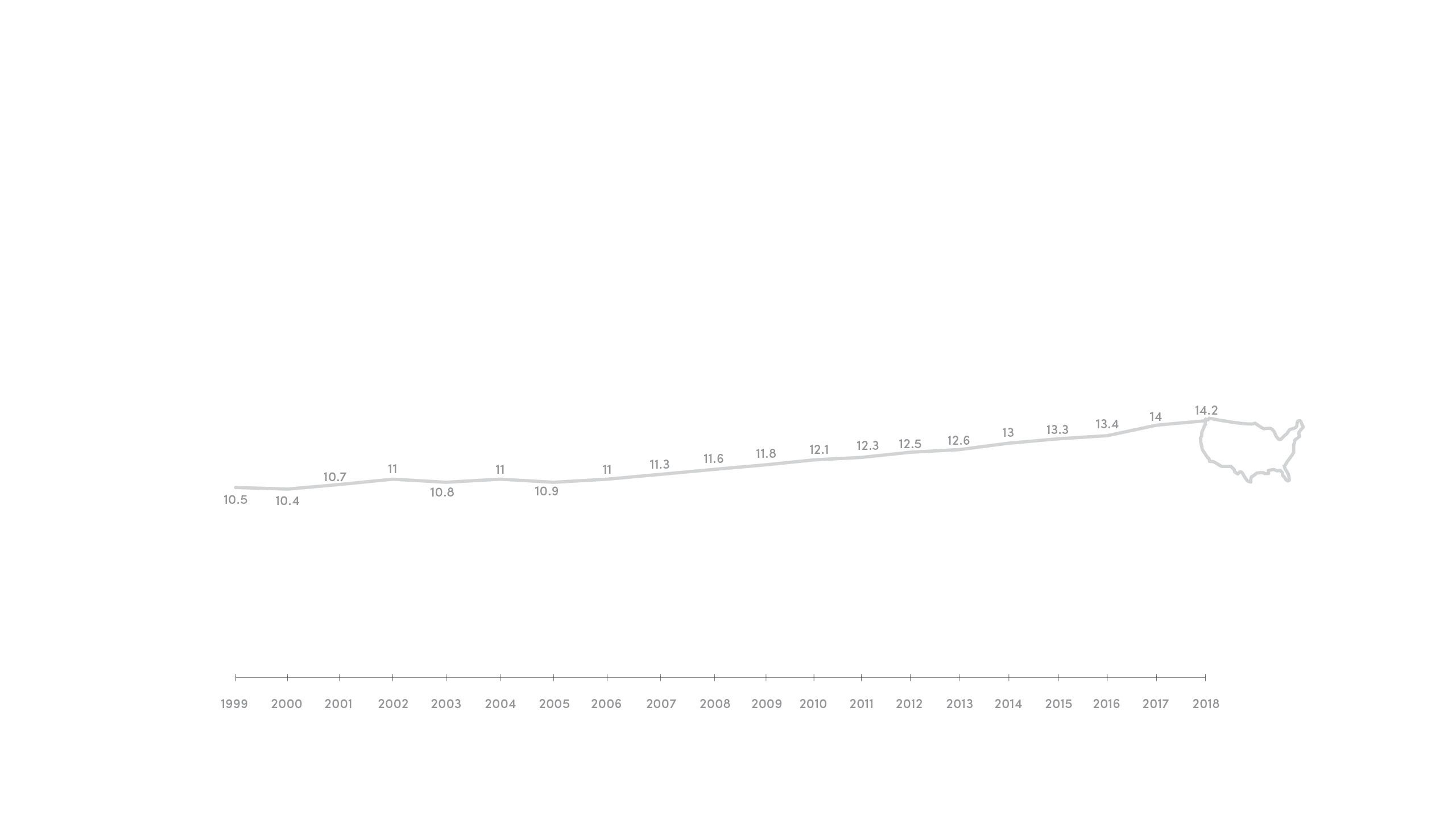

Utah’s overall suicide rate has soared above the national average for more than 20 years.

In fact, Utah has the 6th highest suicide rate in the nation.

UTAH TEEN SUICIDES PER YEAR

In 1999, 12 Utah teens committed suicide. By 2019, that number more than tripled to 42. A consistent upward spike, alongside some small dips, throughout this time period are marked along this line. (Label: year = number of suicides.)

UTAH TEEN SUICIDES PER YEAR

In 1999, 12 Utah teens committed suicide. By 2019, that number more than tripled to 42. A consistent upward spike, alongside some small dips, throughout this time period are marked along this line. (Label: year = number of suicides.)

UTAH YOUTH SUICIDES

Suicide is the

#1 cause of death

for Utahns aged 10-17

Utah children

as young as 9 years old

have expressed thoughts of

depression and suicide

Utah’s youth suicide

rate has more than

tripled

in the last two decades alone

UTAH SUICIDES

It’s not only teens, though.

Utah’s overall suicide

rate has soared above

the national average

for more than 20 years

In fact, Utah has the

6th highest suicide rate

in the nation.

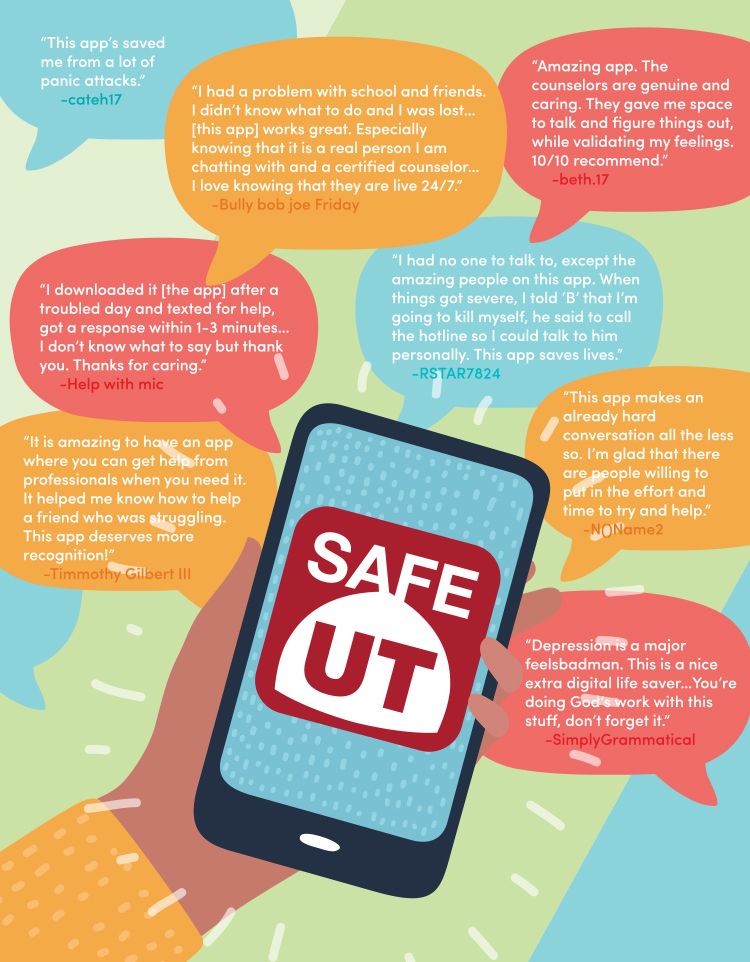

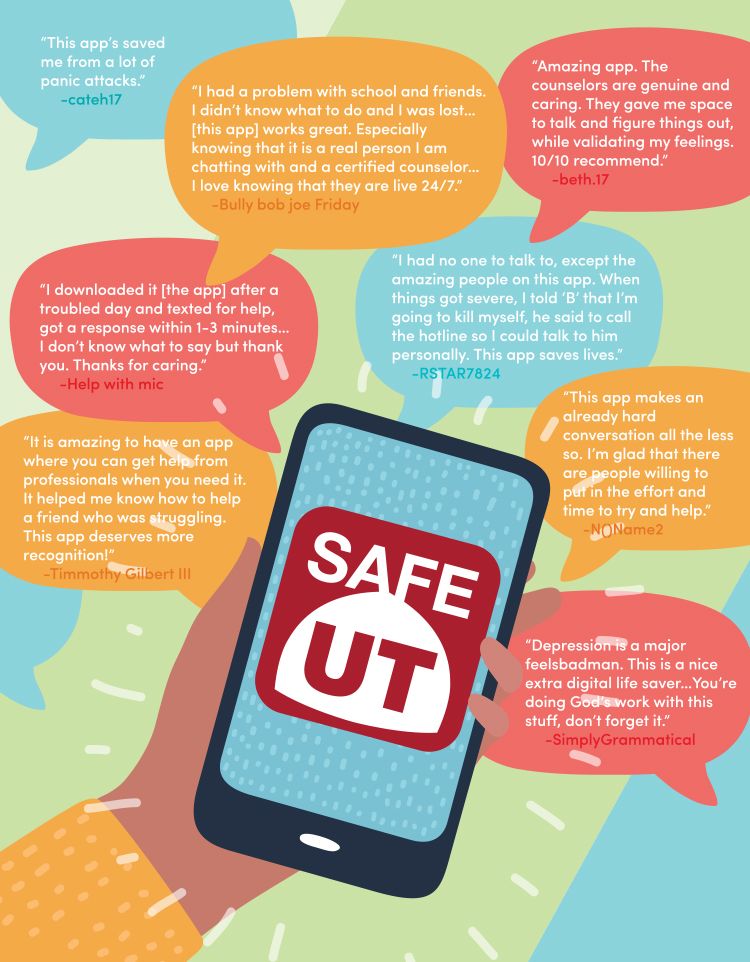

SAFEUT USER REVIEWS FROM THE APP STORE

In 2019, the SafeUT app received 30,000+ submissions from Utah students in need of mental health counseling.

SAFEUT USER REVIEWS FROM THE APP STORE

In 2019, the SafeUT app received 30,000+ submissions from Utah students in need of mental health counseling.

Suicide isn’t often a decision made in a single moment. It can be a choice to end life after a string of painful experiences: job stress, a breakup, the inability to connect with others. No one is immune to these struggles.

Julia Ludlow was one of the lucky ones—with her parents’ help, she soon saw a mental health counselor. But for every 100,000 Utah children in need of mental health care, there are only six child psychiatrists. Between physician shortages and spotty health insurance coverage, struggling teens are often forced to wait several weeks for a simple consultation—weeks beset by the very issues they sought help for in the first place.

Children like Julia deserve better. So how do we do that? To help a suffering, tech-dependent generation, can we meet them where they are? The answer lies in the SafeUT app.

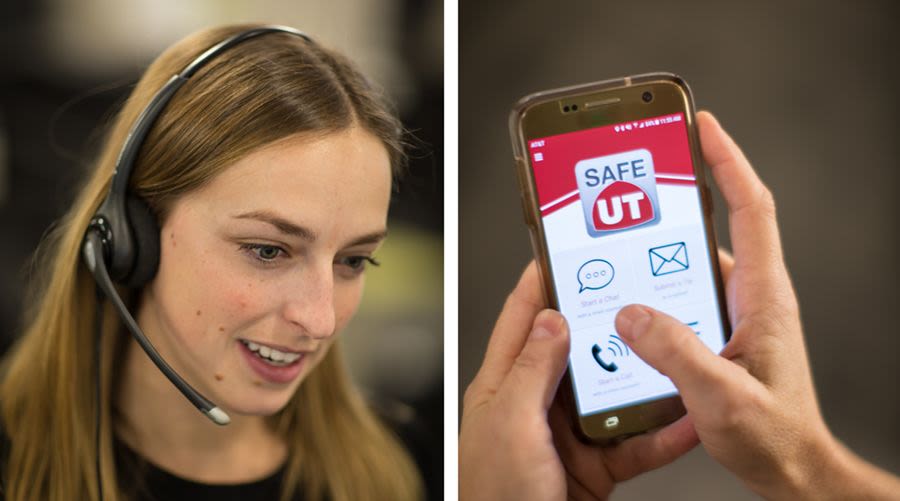

Free. Confidential. Available 24/7. Launched in 2016 by a statewide commission, SafeUT taps into the tech divide by offering around-the-clock crisis intervention. Users can avoid lengthy waitlists, psychiatric provider shortages, and costly deductibles to find help right when and where they need it.

That often means late at night, as the app’s busiest times are between 7 pm and midnight. During this time, students are out of school, have eaten dinner with their family, and are alone in their rooms where they feel safest. Here, problems pushed down during the day resurface: bullying, anxiety, substance abuse, and general stress. Usually, confiding in friends offers no solution; talking to parents brings no comfort.

Licensed therapists from the University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI) are humbled to take each call. They recognize just how vulnerable a young life surrounded by screens can be. “It used to be you’d go to school and be bullied during the day,” says Ross Van Vranken, executive director of UNI. “Now it’s 24/7 if somebody wants to do that.”

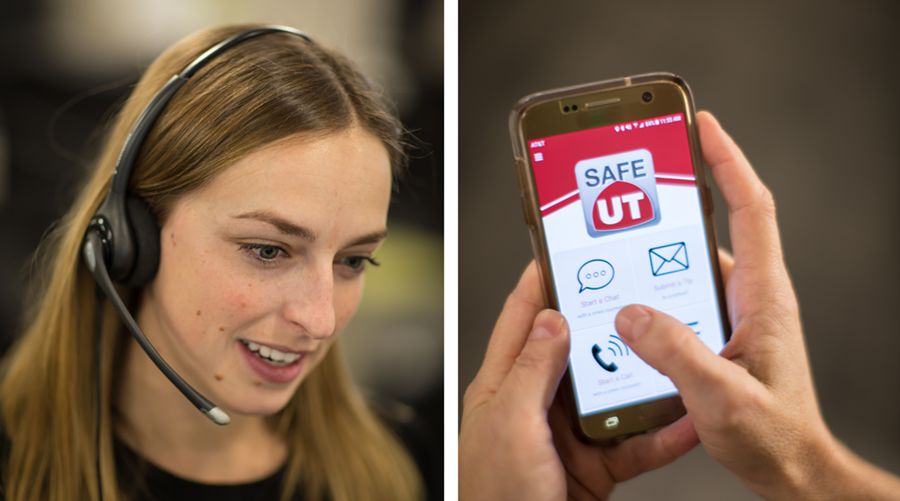

A therapist (left) answers a call from a SafeUT app user. At right, a texter navigates to the SafeUT app on their phone.

Photos by Charlie Ehlert

A therapist (left) answers a call from a SafeUT app user. At right, a texter navigates to the SafeUT app on their phone.

Photos by Charlie Ehlert

When it comes to threats of suicide, UNI therapists are tasked with gleaning enough information in time to perform an “active rescue” if needed. These rescues are not uncommon, and the anonymity of the app—while a source of comfort for users—often means therapists will not know the fate of those reaching out.

Shouldering that burden isn’t always easy, as most SafeUT therapists will admit. One counselor, though, calls it “an honor to sit with someone in that darkest of spaces.” The work, however difficult, is certainly worthwhile. After all, the prize is life.

*As of August 2019, UNI will be incorporated into the Huntsman Mental Health Institute with an expected launch in January 2021.

Suicide isn’t often a decision made in a single moment. It can be a choice to end life after a string of painful experiences: job stress, a breakup, the inability to connect with others. No one is immune to these struggles.

Julia Ludlow was one of the lucky ones—with her parents’ help, she soon saw a mental health counselor. But for every 100,000 Utah children in need of mental health care, there are only six child psychiatrists. Between physician shortages and spotty health insurance coverage, struggling teens are often forced to wait several weeks for a simple consultation—weeks beset by the very issues they sought help for in the first place.

Children like Julia deserve better. So how do we do that? To help a suffering, tech-dependent generation, can we meet them where they are? The answer lies in the SafeUT app.

SafeUT user reviews from the APP Store

In 2019, the SafeUT app received 30,000+ submissions from Utah students in need of mental health counseling.

SafeUT user reviews from the APP Store

In 2019, the SafeUT app received 30,000+ submissions from Utah students in need of mental health counseling.

Free. Confidential. Available 24/7. Launched in 2016 by a statewide commission, SafeUT taps into the tech divide by offering around-the-clock crisis intervention. Users can avoid lengthy waitlists, psychiatric provider shortages, and costly deductibles to find help right when and where they need it.

That often means late at night, as the app’s busiest times are between 7 pm and midnight. During this time, students are out of school, have eaten dinner with their family, and are alone in their rooms where they feel safest. Here, problems pushed down during the day resurface: bullying, anxiety, substance abuse, and general stress. Usually, confiding in friends offers no solution; talking to parents brings no comfort.

Licensed therapists from the University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI) are humbled to take each call. They recognize just how vulnerable a young life surrounded by screens can be. “It used to be you’d go to school and be bullied during the day,” says Ross Van Vranken, executive director of UNI. “Now it’s 24/7 if somebody wants to do that.”

A SafeUT therapist in the call center; a texter uses the SafeUT app on their phone. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

A SafeUT therapist in the call center; a texter uses the SafeUT app on their phone. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

When it comes to threats of suicide, UNI therapists are tasked with gleaning enough information in time to perform an “active rescue” if needed. These rescues are not uncommon, and the anonymity of the app—while a source of comfort for users—often means therapists will not know the fate of those reaching out.

Shouldering that burden isn’t always easy, as most SafeUT therapists will admit. One counselor, though, calls it “an honor to sit with someone in that darkest of spaces.” The work, however difficult, is certainly worthwhile. After all, the prize is life.

*As of August 2019, UNI will be incorporated into the Huntsman Mental Health Institute with an expected launch in January 2021.

THE PROBLEM

Utah ranks

6th

in the nation

for highest number

of suicides

There are

only 6

child psychiatrists

for every 100,000

children in Utah.

The national average

is approximately

twice that

THE SOLUTION

To help bridge this gap,

SafeUT provides mental

health counseling

to more than

734K

students across

the state

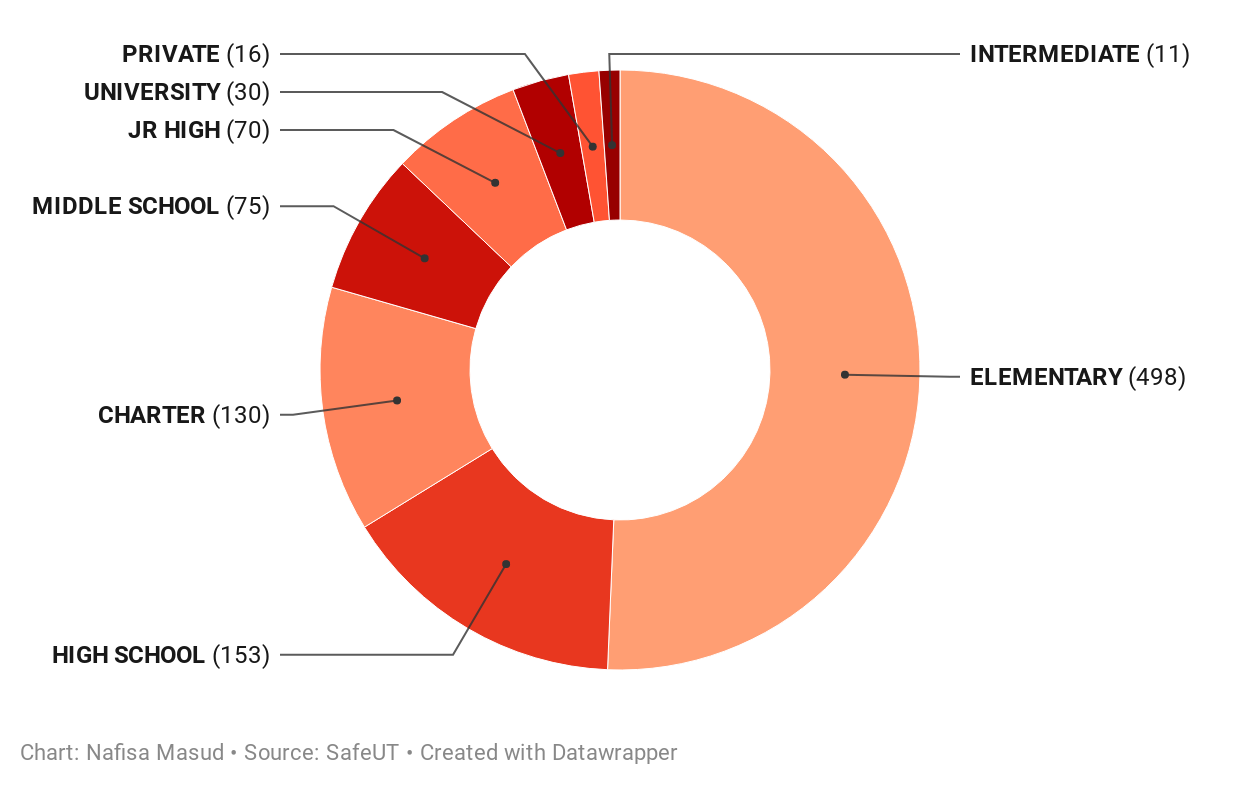

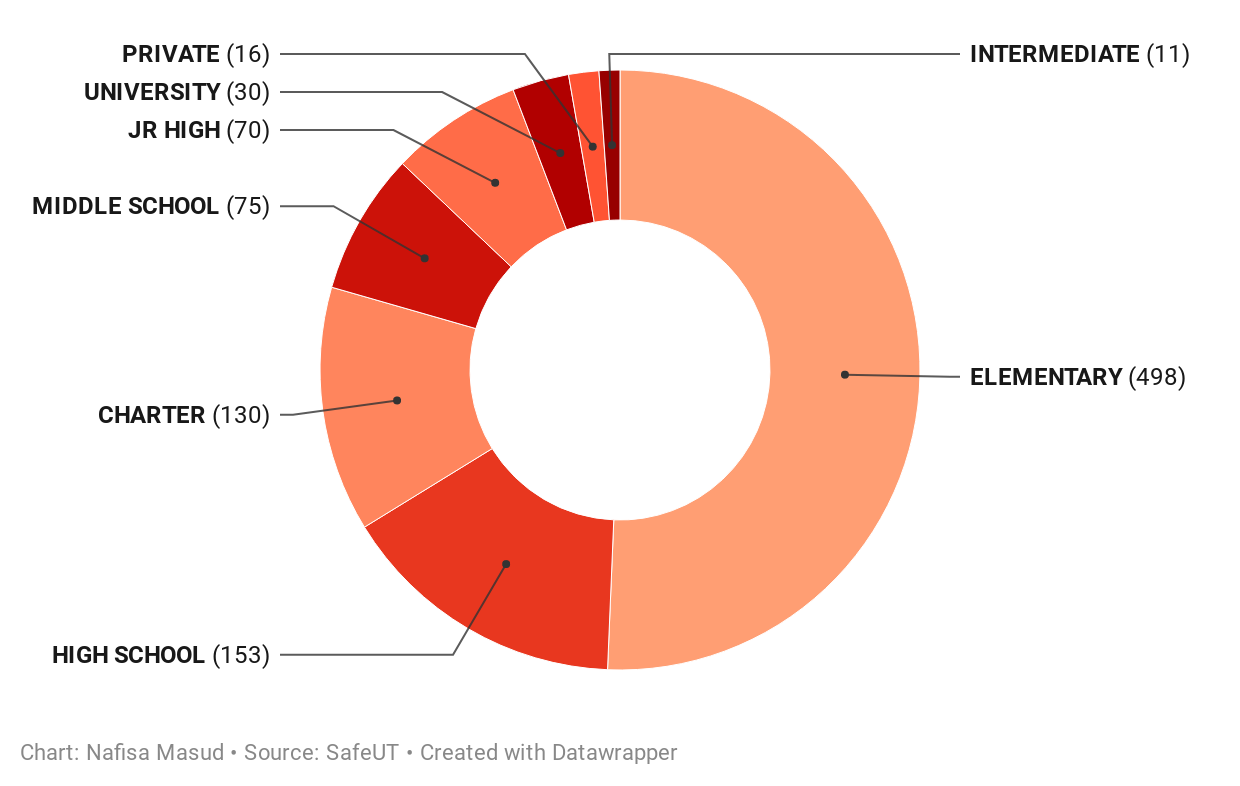

In the four years since its creation, the number of tips and chats submitted through the app has soared by more than 600 percent. That surge is one of many reasons why nearly 1,000 schools have enrolled in the SafeUT app, at all levels of education.

The majority of SafeUT enrolled schools are at the elementary and high school level, where children are often most at-risk.

The majority of SafeUT enrolled schools are at the elementary and high school level, where children are often most at-risk.

For Lori Thorn, director of student services at Alpine School District, enrolling 76 of her schools in SafeUT has given students a safe space at their fingertips and identified at-risk youth who may otherwise fall under the radar.

"The more students use this, the more the perception of getting help has changed," she says. "That's exciting, because it's a huge battle to reach out for help."

SafeUT use by county: the larger the circle, the more schools enrolled. (As you hover over each county, you'll see the number of schools.)

SafeUT has further expansions in the works, including one for the Utah National Guard that extends mental health support to more than 7,000 service members and their families. In its first six months alone, the SafeUT National Guard app was downloaded by 1,000 members. And this year, SafeUT received the 2020 Best of State Award for Best Web-based Community Resource.

In the four years since its creation, the number of tips and chats submitted through the app has soared by more than 600 percent. That surge is one of many reasons why nearly 1,000 schools have enrolled in the SafeUT app, at all levels of education.

The majority of SafeUT enrolled schools are at the elementary and high school level, where children are often most at-risk.

The majority of SafeUT enrolled schools are at the elementary and high school level, where children are often most at-risk.

For Lori Thorn, director of student services at Alpine School District, enrolling 76 of her schools in SafeUT has given students a safe space at their fingertips and identified at-risk youth who may otherwise fall under the radar.

"The more students use this, the more the perception of getting help has changed," she says. "That's exciting, because it's a huge battle to reach out for help."

SafeUT app use by county (the larger the circle, the more schools enrolled).

SafeUT app use by county (the larger the circle, the more schools enrolled).

SafeUT has further expansions in the works, including one for the Utah National Guard that extends mental health support to more than 7,000 service members and their families. In its first six months alone, the SafeUT National Guard app was downloaded by 1,000 members. And this year, SafeUT received the 2020 Best of State Award for Best Web-based Community Resource.

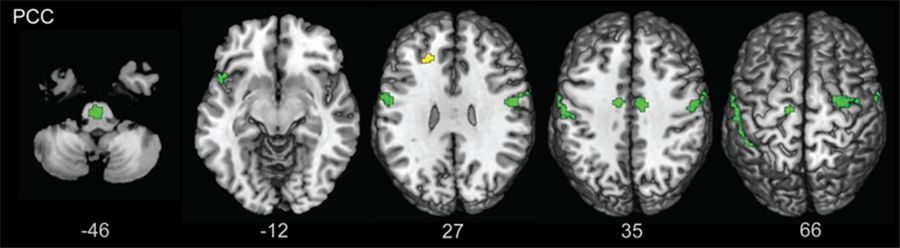

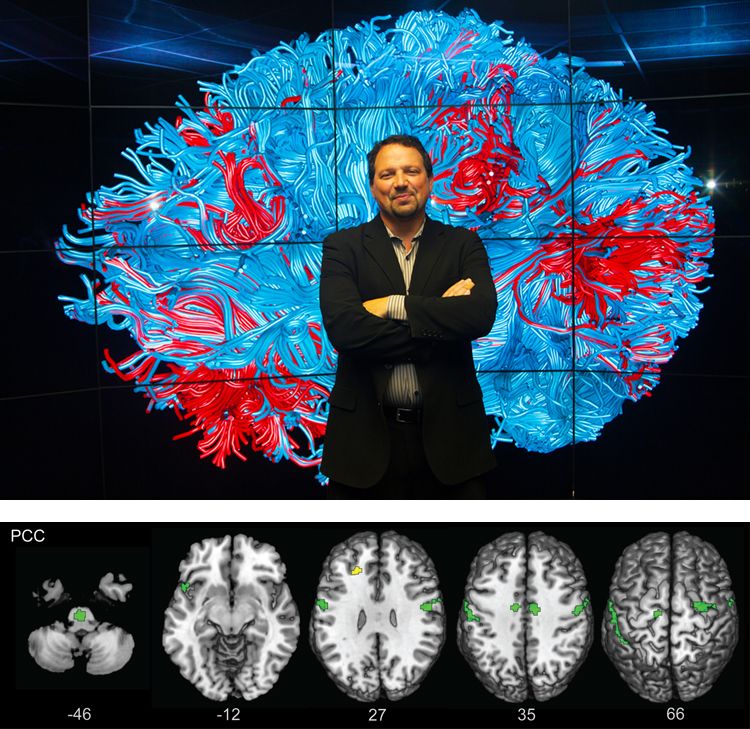

The moments preceding suicide are an opportunity to understand those populations vulnerable to suicide. Scott A. Langenecker, PhD (background, at right) is one of several U of U researchers committed to studying the link between mental illness, suicide, and the brain.

The fMRI results of one such study (above) show the effects of childhood adversity on the brain. Across various portions of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), results suggest that childhood adversity disrupts how the brain is wired, making it more difficult for a person to focus and control their emotions, including negative thoughts. These disruptions are colored in green and take place across the brain, from the base near the cerebellum (-46) all the way to the top of the brain (66). Photos by Vibhu Rangavasan (background, at right) and Scott A. Langenecker, PhD

The fMRI results of one such study (above) show the effects of childhood adversity on the brain. Across various portions of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), results suggest that childhood adversity disrupts how the brain is wired, making it more difficult for a person to focus and control their emotions, including negative thoughts. These disruptions are colored in green and take place across the brain, from the base near the cerebellum (-46) all the way to the top of the brain (66). Photos by Vibhu Rangavasan (background, at right) and Scott A. Langenecker, PhD

And when we understand those vulnerable to suicide, we can better support them before it’s too late. Douglas D. Gray, MD, professor of psychiatry at the University of Utah, has been doing just that.

He first started studying the social and cultural factors behind Utah’s rising youth suicides in the late 1990s. At the time, Gray was one of only two people studying suicide in the state. “To help educate people, I used to fill my old Honda Civic with training pamphlets and hand them out on the weekends,” he says. “It was the loneliest job in town.”

Douglas D. Gray, MD. Photo by Al Hartmann, The Salt Lake Tribune

Douglas D. Gray, MD. Photo by Al Hartmann, The Salt Lake Tribune

Now, 20 years later, Gray is astounded by how far Utah has come in researching and understanding suicide. A team of legislative champions, state coordinators, medical examiners, and student mobile crisis team members now meet struggling Utahns early on to provide support and solutions.

Thanks to researchers like Gray, in the past three years alone, the University of Utah has secured funding of more than $125 million to conduct 131 research projects on mental illness and suicide prevention. “Eight years ago, I thought I would retire and nothing for suicide would have been done,” Gray says. "Now, when I do retire, I can retire in peace. Things will keep moving forward.”

Utah’s rising rates point to a larger issue—a troubling deficit in health care access. A third of Utah adults suffer from depression, and more than half of those lack access to treatment. Utah ranks last in the United States for mental health care resources.

To address this deficit, UNI helps hedge against access issues by offering resources on depression, mood disorders, and substance abuse. And just this year, the Huntsman Foundation committed $150 million to establishing a robust response to this crisis: the Huntsman Mental Health Institute.

“The first Huntsman generation made remarkable advancements in cancer research,” Gray says. “The second generation is focusing on the next important issue: mental health care and the stigma that comes with it.”

The moments preceding suicide are an opportunity to understand those populations vulnerable to suicide. Scott A. Langenecker, PhD (below) is one of several U of U researchers committed to studying the link between mental illness, suicide, and the brain.

The fMRI results of one such study (above) show the effects of childhood adversity on the brain. Across various portions of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), results suggest that childhood adversity disrupts how the brain is wired, making it more difficult for a person to focus and control their emotions, including negative thoughts. These disruptions are colored in green and take place across the brain, from the base near the cerebellum (-46) all the way to the top of the brain (66). Photos by Vibhu Rangavasan (top) and Scott A. Langenecker, PhD

The fMRI results of one such study (above) show the effects of childhood adversity on the brain. Across various portions of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), results suggest that childhood adversity disrupts how the brain is wired, making it more difficult for a person to focus and control their emotions, including negative thoughts. These disruptions are colored in green and take place across the brain, from the base near the cerebellum (-46) all the way to the top of the brain (66). Photos by Vibhu Rangavasan (top) and Scott A. Langenecker, PhD

And when we understand those vulnerable to suicide, we can better support them before it’s too late. Douglas D. Gray, MD, professor of psychiatry at the University of Utah, has been doing just that.

He first started studying the social and cultural factors behind Utah’s rising youth suicides in the late 1990s. At the time, Gray was one of only two people studying suicide in the state. “To help educate people, I used to fill my old Honda Civic with training pamphlets and hand them out on the weekends,” he says. “It was the loneliest job in town.”

Douglas D. Gray, MD. Photo by Al Hartmann, The Salt Lake Tribune

Douglas D. Gray, MD. Photo by Al Hartmann, The Salt Lake Tribune

Now, 20 years later, Gray is astounded by how far Utah has come in researching and understanding suicide. A team of legislative champions, state coordinators, medical examiners, and student mobile crisis team members now meet struggling Utahns early on to provide support and solutions.

Thanks to researchers like Gray, in the past three years alone, the University of Utah has secured funding of more than $125 million to conduct 131 research projects on mental illness and suicide prevention. “Eight years ago, I thought I would retire and nothing for suicide would have been done,” Gray says.

“Now, when I do retire, I can retire in peace. Things will keep moving forward.”

Utah’s rising rates point to a larger issue—a troubling deficit in health care access. A third of Utah adults suffer from depression, and more than half of those lack access to treatment. Utah ranks last in the United States for mental health care resources.

To address this deficit, UNI helps hedge against access issues by offering resources on depression, mood disorders, and substance abuse. And just this year, the Huntsman Foundation committed $150 million to establishing a robust response to this crisis: the Huntsman Mental Health Institute.

“The first Huntsman generation made remarkable advancements in cancer research,” Gray says. “The second generation is focusing on the next important issue: mental health care and the stigma that comes with it.”

RESEARCH INNOVATION

1 in 5

Utah adults

suffer from poor

mental health, but

Utah ranks

51st

in the nation

for access to

needed resources

In the last three years,

the University of Utah

has conducted:

131

suicide research projects

across 18 departments

with funding of more than

$125M

These

studies

explore suicide’s link to

genetics, veterans,

postpartum depression,

trauma, sleep,

social dynamics,

and more

In a recent mental health panel hosted by U of U Health at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, Christena Huntsman Durham acknowledged that pervasive power of stigma:

Christena Huntsman Durham speaks at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival panel. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Christena Huntsman Durham speaks at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival panel. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Durham lost her own sister to addiction 10 years ago, teaching her the importance of having a place to find help without judgment. “If you’re at your kid’s soccer game and they sprain their ankle, you go to Urgent Care,” she said. “But if our child or loved one is suffering from mental illness, where do we go?”

We’re working to bridge this gap, but we can’t do it alone. The simplest solution starts with a conversation. Talk. Share. Listen.

In the face of this crisis, as with any other, there’s hope. For the first time in more than a decade, Utah’s suicide rate has stabilized. It’s a small feat, not yet significant, but it marks our place at a critical juncture. Here we ask, “What can we do next, together?”

Christena Huntsman Durham, Jon Huntsman Jr., and Karen Huntsman (top photo, left to right) at the announcement of the Huntsman Foundation’s $150 million donation on November 4, 2019. That historic gift, the largest single donation given to the U, will broaden mental health care access across the state and expand the prestigious University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI) under the new Huntsman Mental Health Institute name. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

Christena Huntsman Durham, Jon Huntsman Jr., and Karen Huntsman (top photo, left to right) at the announcement of the Huntsman Foundation’s $150 million donation on November 4, 2019. That historic gift, the largest single donation given to the U, will broaden mental health care access across the state and expand the prestigious University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI) under the new Huntsman Mental Health Institute name. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

In a recent mental health panel hosted by U of U Health at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, Christena Huntsman Durham acknowledged that pervasive power of stigma:

Christena Huntsman Durham speaks at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival panel. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Christena Huntsman Durham speaks at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival panel. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Durham lost her own sister to addiction 10 years ago, teaching her the importance of having a place to find help without judgment. “If you’re at your kid’s soccer game and they sprain their ankle, you go to Urgent Care,” she said. “But if our child or loved one is suffering from mental illness, where do we go?”

We’re working to bridge this gap, but we can’t do it alone. The simplest solution starts with a conversation. Talk. Share. Listen.

In the face of this crisis, as with any other, there’s hope. For the first time in more than a decade, Utah’s suicide rate has stabilized. It’s a small feat, not yet significant, but it marks our place at a critical juncture. Here we ask, “What can we do next, together?”

EXPANDING CARE FOR ALL

The Huntsman Foundation

has pledged

$150M

to provide mental health

care for students and

underserved communities

The University

Neuropsychiatric Institute

(UNI) provides mental

health care for Utah

communities through

170

licensed inpatient staff

UNI offers

services

focusing on

children and adolescents,

maternal mental health,

substance use disorders,

and more

In FY2019,

UNI provided

51K+

unique encounters

of inpatient, outpatient, and

day treatment services

Thanks to counseling and family intervention following her suicide attempt, Julia Ludlow—now 17—is focused on the future. She finds it easier to open up about her thoughts, even the dark ones. “There’s less of a stigma around my feelings,” she says. “My depression is less mine and more shared.”

When Julia’s father talks about his daughter since her suicide attempt, pride and pain fight for prominence in his voice, even as it breaks with relief. “She’s very compassionate,” he says. “What I love about her is she’s taking her experience and using it in a way to help those around her.”

Julia Ludlow, former Rep. Ben McAdams, and others speak in support of suicide prevention programming at Utah schools. Photos by Charlie Ehlert.

Julia Ludlow, former Rep. Ben McAdams, and others speak in support of suicide prevention programming at Utah schools. Photos by Charlie Ehlert.

Julia now shares her story to help inspire greater change, recently alongside former Rep. Ben McAdams (D-Utah) in support of $2 million in funding for school-based suicide prevention programs. “As risk factors like depression and crisis become something we don’t hide in the shadows, [people] are looking for somebody to talk to,” McAdams said in a Salt Lake Tribune article. “We want to make sure those resources continue to be available... to people who need them.”

Julia is still the same young woman with a gentle smile, but she speaks now with a newfound confidence. She’s surer of herself, at peace. And she knows she’s not alone.

Thanks to counseling and family intervention following her suicide attempt, Julia Ludlow—now 17—is focused on the future. She finds it easier to open up about her thoughts, even the dark ones. “There’s less of a stigma around my feelings,” she says. “My depression is less mine and more shared.”

When Julia’s father talks about his daughter since her suicide attempt, pride and pain fight for prominence in his voice, even as it breaks with relief. “She’s very compassionate,” he says. “What I love about her is she’s taking her experience and using it in a way to help those around her.”

Julia now shares her story to help inspire greater change, recently alongside former Rep. Ben McAdams (D-Utah) in support of $2 million in funding for school-based suicide prevention programs. “As risk factors like depression and crisis become something we don’t hide in the shadows, [people] are looking for somebody to talk to,” McAdams said in a Salt Lake Tribune article. “We want to make sure those resources continue to be available... to people who need them.”

Julia is still the same young woman with a gentle smile, but she speaks now with a newfound confidence. She’s surer of herself, at peace. And she knows she’s not alone.

Julia Ludlow, former Rep. Ben McAdams, and others speak in support of suicide prevention programming at Utah schools. Photos by Charlie Ehlert.

Julia Ludlow, former Rep. Ben McAdams, and others speak in support of suicide prevention programming at Utah schools. Photos by Charlie Ehlert.

“State of Suffering”

Story and concept by Nafisa Masud

Design by:

Jesse Colby

Production support by:

Jessica Cagle and Mitch Sears

Extra thanks to

Stephen Dark