Expanding Access, Education, and Jobs to All Corners of the State

December 14, 2020

America’s traditional brick-and-mortar health care system, with facilities and experts centered in urban and suburban areas, is clearly not designed for the 20 percent of Americans who live in rural regions. Of those 65 million or so citizens, 80 percent are considered medically underserved. Their life expectancies run a full decade shorter. Rates of poverty, obesity, and diabetes are nearly 25 percent higher. Convenient access to health care is reduced precisely where it’s needed most.

Utah has managed to buck some of the most alarming national trends. While 130 rural hospitals across the US have closed since 2010, not a single one in the Beehive State has suffered the same fate. And technological solutions like telehealth have actually started to expand access for Utah’s rural residents. But physician shortages are still a major problem. Of Utah’s doctors aged 35 and younger, only 3 percent practice in rural counties. Solving that problem requires intensive long-term work.

“Your abilities shouldn’t be limited by your circumstances” is a maxim that’s fundamental to the American Dream. But reality is often a lot more complicated. Take Kade Shumway Lyman, MD (left). A decade ago, the 15-year-old told his teacher at San Juan High School that he wanted to be a doctor. Instead of encouraging him, the well-meaning teacher hesitated. Nearly a decade had passed since the last native of Blanding, Utah—population 3,696, with one hospital and fewer than 10 doctors—had gone to medical school, they said. It’s an expensive and demanding decision, they said. Consider becoming a podiatrist or a physician assistant instead, they advised. So he listened.

Growing up in Blanding, Kade remembers having to drive 90 minutes to Cortez, Colorado to buy a pair of socks. Located midway between red rock mecca Moab, Monument Valley’s desolate beauty, and sovereign territory of the Navajo Nation and White Mesa Utes, Blanding is the 107th largest city in the state. Physician shortages plague the area—in 2017, no doctors practicing in San Juan County were under the age of 35. Blanding has very limited subspecialty care, too, meaning a serious health problem requires an AirMed flight to the University of Utah.

Two years after Kade had shelved his plans to become a physician, his perspective shifted when several U of U School of Medicine representatives visited Blanding. These medical students volunteering with the Utah Rural Outreach Program (UROP), now part of the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE), crisscross the state during winter and spring breaks. Their mission is to address a long-standing dearth of doctors in rural counties by encouraging local high schoolers to consider the rewards of health care careers.

One of the medical students who visited Blanding was from the central Utah town of Beaver and had played football against Lyman’s San Juan High School Broncos. Talking to him, Kade realized that medical students were “normal people, not geniuses,” he says. “All medical school takes is dedication and hard work.”

Kade went on to achieve his unlikely dream of enrolling at the University of Utah School of Medicine. Years later, he returned to Blanding himself as a UROP representative to promote medicine to students like his younger siblings—one of whom is now a physician, while the other is preparing to take the MCAT—and friends. “I felt like I could really connect with students there because I knew their teachers, all the doctors that were providing them care, and even other students who had been able to get into health care,” Kade says.

Outreach programs hosted by University of Utah School of Medicine reach students in small towns around the state. Kade Lyman believes they make a difference, too. “In the classes older than me, it had been 10 years since a San Juan High graduate had gone to medical school. Since I graduated, several students have entered medical school each year.” Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Outreach programs hosted by University of Utah School of Medicine reach students in small towns around the state. Kade Lyman believes they make a difference, too. “In the classes older than me, it had been 10 years since a San Juan High graduate had gone to medical school. Since I graduated, several students have entered medical school each year.” Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Now in his fifth and final year of residency at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, a Level 1 Trauma Center, Kade plans to complete his fellowship in sports medicine, which he says is the most versatile specialty for orthopedic surgeons. “Orthopedic surgeons in large cities try to carve out niches in which to practice, often specializing in one part of the body or a small handful of procedures,” Kade says. “I want to do as much as I can to keep my scope of practice broad to better serve my community.”

Kade has signed a contract with a health care company back home in San Juan County and will be returning to practice as an orthopedic surgeon. His younger brother, Dane, has also signed a contract to return home and practice as a family physician. “We will be moving back the same year—2022,” Kade says. “I want my children to grow up in the same close-knit and supportive community I did.” While big-city residents might hesitate at the thought of a small-town practice, Kade, a fifth-generation native of Blanding, knows the beauty of life for a rural clinician: good money, a wide variety of procedures, and a broader scope of practice.

Contrary to Thomas Wolfe’s famous dictum, Kade’s journey proves that you actually can go home again.

While big-city residents might hesitate at the thought of a small-town practice, Kade, a fifth-generation native of Blanding, knows the beauty of life for a rural clinician.

Photo by Kim Montella

While big-city residents might hesitate at the thought of a small-town practice, Kade, a fifth-generation native of Blanding, knows the beauty of life for a rural clinician.

Photo by Kim Montella

“Your abilities shouldn’t be limited by your circumstances” is a maxim that’s fundamental to tahe American Dream. But reality is often a lot more complicated. Take Kade Shumway Lyman, MD. A decade ago, the 15-year-old told his teacher at San Juan High School that he wanted to be a doctor. Instead of encouraging him, the well-meaning teacher hesitated. Nearly a decade had passed since the last native of Blanding, Utah—population 3,696, with one hospital and fewer than 10 doctors—had gone to medical school, they said. It’s an expensive and demanding decision, they said. Consider becoming a podiatrist or a physician assistant instead, they advised. So he listened.

Growing up in Blanding, Kade remembers having to drive 90 minutes to Cortez, Colorado to buy a pair of socks. Located midway between red rock mecca Moab, Monument Valley’s desolate beauty, and sovereign territory of the Navajo Nation and White Mesa Utes, Blanding is the 107th largest city in the state. Physician shortages plague the area—in 2017, no doctors practicing in San Juan County were under the age of 35. Blanding has very limited subspecialty care, too, meaning a serious health problem requires an AirMed flight to the University of Utah.

Two years after Kade had shelved his plans to become a physician, his perspective shifted when several U of U School of Medicine representatives visited Blanding. These medical students volunteering with the Utah Rural Outreach Program (UROP), now part of the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE), crisscross the state during winter and spring breaks. Their mission is to address a long-standing dearth of doctors in rural counties by encouraging local high schoolers to consider the rewards of health care careers.

One of the medical students who visited Blanding was from the central Utah town of Beaver and had played football against Lyman’s San Juan High School Broncos. Talking to him, Kade realized that medical students were “normal people, not geniuses,” he says. “All medical school takes is dedication and hard work.”

Kade Lyman was the first Blanding, Utah, native to leave for medical school in a decade. Photo by Kim Montella

Kade Lyman was the first Blanding, Utah, native to leave for medical school in a decade. Photo by Kim Montella

Kade went on to achieve his unlikely dream of enrolling at the University of Utah School of Medicine. Years later, he returned to Blanding himself as a UROP representative to promote medicine to students like his younger siblings—one of whom is now a physician, while the other is preparing to take the MCAT—and friends. “I felt like I could really connect with students there because I knew their teachers, all the doctors that were providing them care, and even other students who had been able to get into health care,” Kade says. “In the classes older than me, it had been 10 years since a San Juan High graduate had gone to medical school. Since I graduated, several students have entered medical school each year.”

Now in his fifth and final year of residency at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, a Level 1 Trauma Center, Kade plans to complete his fellowship in sports medicine, which he says is the most versatile specialty for orthopedic surgeons. “Orthopedic surgeons in large cities try to carve out niches in which to practice, often specializing in one part of the body or a small handful of procedures,” Kade says. “I want to do as much as I can to keep my scope of practice broad to better serve my community.”

Kade has signed a contract with a health care company back home in San Juan County and will be returning to practice as an orthopedic surgeon. His younger brother, Dane, has also signed a contract to return home and practice as a family physician. “We will be moving back the same year—2022,” Kade says. “I want my children to grow up in the same close-knit and supportive community I did.” While big-city residents might hesitate at the thought of a small-town practice, Kade, a fifth-generation native of Blanding, knows the beauty of life for a rural clinician: good money, a wide variety of procedures, and a broader scope of practice.

Contrary to Thomas Wolfe’s famous dictum, Kade’s journey proves that you actually can go home again.

THE PROBLEM

10%

of Utahns live in

rural areas

7.9%

of physicians

practice in Rural

communities

Every year, so many

rural physicians retire

that the state would need

19

new ones just to fill

their shoes

THE SOLUTION

That’s why rural outreach

is so important

Rural students who

receive multiple years of

medical training are

10 times

more likely to practice

in a rural setting

Intensive third-year rural

curriculum and community

preceptorships can increase

the recruitment rate of

rural students by

59%

One medical student returning to his rural roots can make a big difference. The impact is even more pronounced when medical residents from non-rural backgrounds are exposed to life outside of the big city. That’s another key part of RUUTE’s outreach efforts: providing young doctors who have come to Utah for their clinical training an opportunity to work in rural communities. These residents are able to support local health care providers and provide close-to-home, quality care for the community.

“It’s a win-win for everyone,” says Kylie Christensen, MPH, associate director of RUUTE & Regional Affairs. “Our residents go into these communities and build their cultural competencies while offering services that rural clinics and hospitals need.” The RUUTE program strives to meet the particular needs of a community by matching the right medical residents to the right places. “Cache Valley in Logan wants OB/GYN,” Christensen says. “Memorial in Panguitch needs family medicine; Beaver Valley wants general surgery. Working together, we can help patients and providers.”

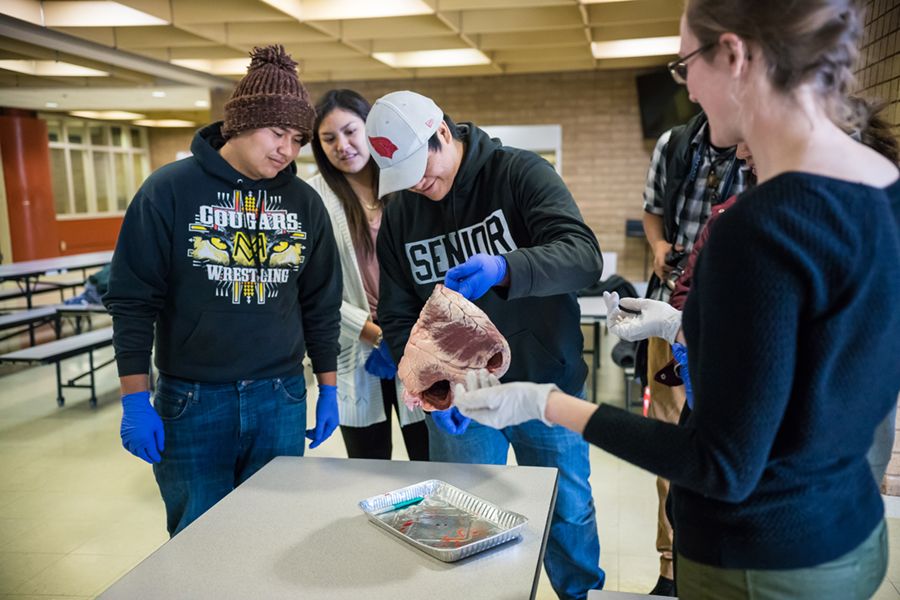

In 2019, the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE) program placed medical students and residents in the following locations starred on the map, among others: Beaver, Blanding, Cedar City, Coalville, Ephraim, Fillmore, Gunnison, Heber, Hurricane, Manti, Moab, Monticello, Moroni, Mt. Pleasant, Orem, Panguitch, Price, Richfield, Roy, St. George, and Tooele. Photo illustration by Jesse Colby, map and photograph by Getty images

In 2019, the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE) program placed medical students and residents in the following locations starred on the map, among others: Beaver, Blanding, Cedar City, Coalville, Ephraim, Fillmore, Gunnison, Heber, Hurricane, Manti, Moab, Monticello, Moroni, Mt. Pleasant, Orem, Panguitch, Price, Richfield, Roy, St. George, and Tooele. Photo illustration by Jesse Colby, map and photograph by Getty images

Most of RUUTE’s medical students and residents probably won’t go on to practice in a rural community. But the exposure increases empathy for the unique challenges rural patients face to receive the care they need. And residents gain deep, firsthand knowledge of social determinants of health, from education level to job opportunities to transportation challenges.

“Doing what’s best for patients is different in a rural setting,” says Sarah Tang, MD, a second-year pediatrics resident from Tucson, Arizona. She worked a six-week rotation at Blue Mountain Hospital in Blanding and the Monument Valley and Montezuma Creek clinics on the Navajo Nation. “Traveling to see a specialist at another clinic isn’t really an option, so rural patients rely on a primary care provider’s ability to treat their needs. You don’t fully understand that until you spend time immersed in those communities.”

Matt Chapman, MD, a second-year emergency medicine resident from Lansing, Michigan, worked a three-week rotation at Mountain West Medical Center in Tooele. Even though it’s only 40 miles from Salt Lake City, Chapman realized that Mountain West’s doctors “are used to operating within a different set of resources than I am.” When patients need specialized cardiac or neurological care, “You don’t have consultants at your fingertips,” Chapman says. “Instead, you have to be prepared to transfer patients quickly.”

“The experience was enlightening,” says Chapman, who plans to practice in a rural setting. “It changed my framework for the way I care for patients.” Next year, Chapman will lead a team of seven third-year emergency medicine residents, who will return to Tooele for a month-long rotation with medical students in tow.

Background photo of Lower Calf Creek hike by Dave Titensor

In 2019, the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE) program placed medical students and residents in the following locations starred on the map, among others: Beaver, Blanding, Cedar City, Coalville, Ephraim, Fillmore, Gunnison, Heber, Hurricane, Manti, Moab, Monticello, Moroni, Mt. Pleasant, Orem, Panguitch, Price, Richfield, Roy, St. George, and Tooele. Photo illustration by Jesse Colby, map and photograph by Getty images

In 2019, the Rural & Underserved Utah Training Experience (RUUTE) program placed medical students and residents in the following locations starred on the map, among others: Beaver, Blanding, Cedar City, Coalville, Ephraim, Fillmore, Gunnison, Heber, Hurricane, Manti, Moab, Monticello, Moroni, Mt. Pleasant, Orem, Panguitch, Price, Richfield, Roy, St. George, and Tooele. Photo illustration by Jesse Colby, map and photograph by Getty images

One medical student returning to his rural roots can make a big difference. The impact is even more pronounced when medical residents from non-rural backgrounds are exposed to life outside of the big city. That’s another key part of RUUTE’s outreach efforts: providing young doctors who have come to Utah for their clinical training an opportunity to work in rural communities. These residents are able to support local health care providers and provide close-to-home, quality care for the community.

“It’s a win-win for everyone,” says Kylie Christensen, MPH, associate director of RUUTE & Regional Affairs. “Our residents go into these communities and build their cultural competencies while offering services that rural clinics and hospitals need.” The RUUTE program strives to meet the particular needs of a community by matching the right medical residents to the right places. “Cache Valley in Logan wants OB/GYN,” Christensen says. “Memorial in Panguitch needs family medicine; Beaver Valley wants general surgery. Working together, we can help patients and providers.”

Most of RUUTE’s medical students and residents probably won’t go on to practice in a rural community. But the exposure increases empathy for the unique challenges rural patients face to receive the care they need. And residents gain deep, firsthand knowledge of social determinants of health, from education level to job opportunities to transportation challenges.

“Doing what’s best for patients is different in a rural setting,” says Sarah Tang, MD, a second-year pediatrics resident from Tucson, Arizona. She worked a six-week rotation at Blue Mountain Hospital in Blanding and the Monument Valley and Montezuma Creek clinics on the Navajo Nation. “Traveling to see a specialist at another clinic isn’t really an option, so rural patients rely on a primary care provider’s ability to treat their needs. You don’t fully understand that until you spend time immersed in those communities.”

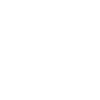

Blanding High School students learn more about the health sciences during a demonstration hosted by RUUTE volunteers. Photo by Sara Lyman

Blanding High School students learn more about the health sciences during a demonstration hosted by RUUTE volunteers. Photo by Sara Lyman

Matt Chapman, MD, a second-year emergency medicine resident from Lansing, Michigan, worked a three-week rotation at Mountain West Medical Center in Tooele. Even though it’s only 40 miles from Salt Lake City, Chapman realized that Mountain West’s doctors “are used to operating within a different set of resources than I am.” When patients need specialized cardiac or neurological care, “You don’t have consultants at your fingertips,” Chapman says. “Instead, you have to be prepared to transfer patients quickly.”

“The experience was enlightening,” says Chapman, who plans to practice in a rural setting. “It changed my framework for the way I care for patients.” Next year, Chapman will lead a team of seven third-year emergency medicine residents, who will return to Tooele for a month-long rotation with medical students in tow.

RUUTE'S IMPACT ACROSS THE STATE

75 medical residents and

students worked

800

hours in clerkship rotations

in 23 rural communities

(most starred on the

map previous)

Last year, they visited

52

schools in

15 Utah counties

They devoted

107 hours

to presentations for

2,885

students

Little RUUTES reached

an additional

307

K-12 students

In total, RUUTE staff and

students drove 27,547 miles

around Utah and spent

149

total weeks volunteering

in rural communities

THE FUTURE IS NOW

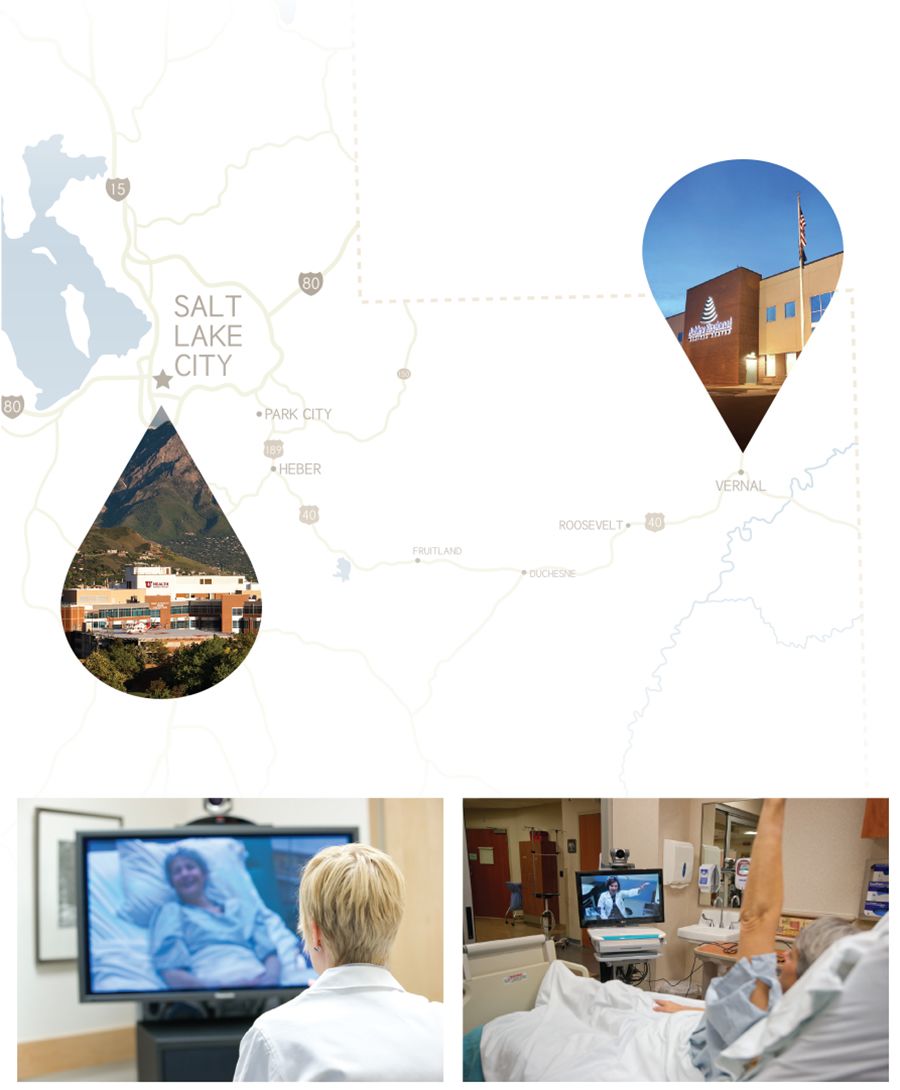

TELEHEALTH EXPANDS ACCESS FOR RURAL RESIDENTS

Picture a small ER in a rural county hospital. A patient has had a stroke. If the sole physician on duty administers a drug called tPA within a narrow window of time, chances are the patient will make a nearly complete recovery. If the physician has to transfer that patient to a larger facility for care, that small treatment window will close and doctors can often do nothing.

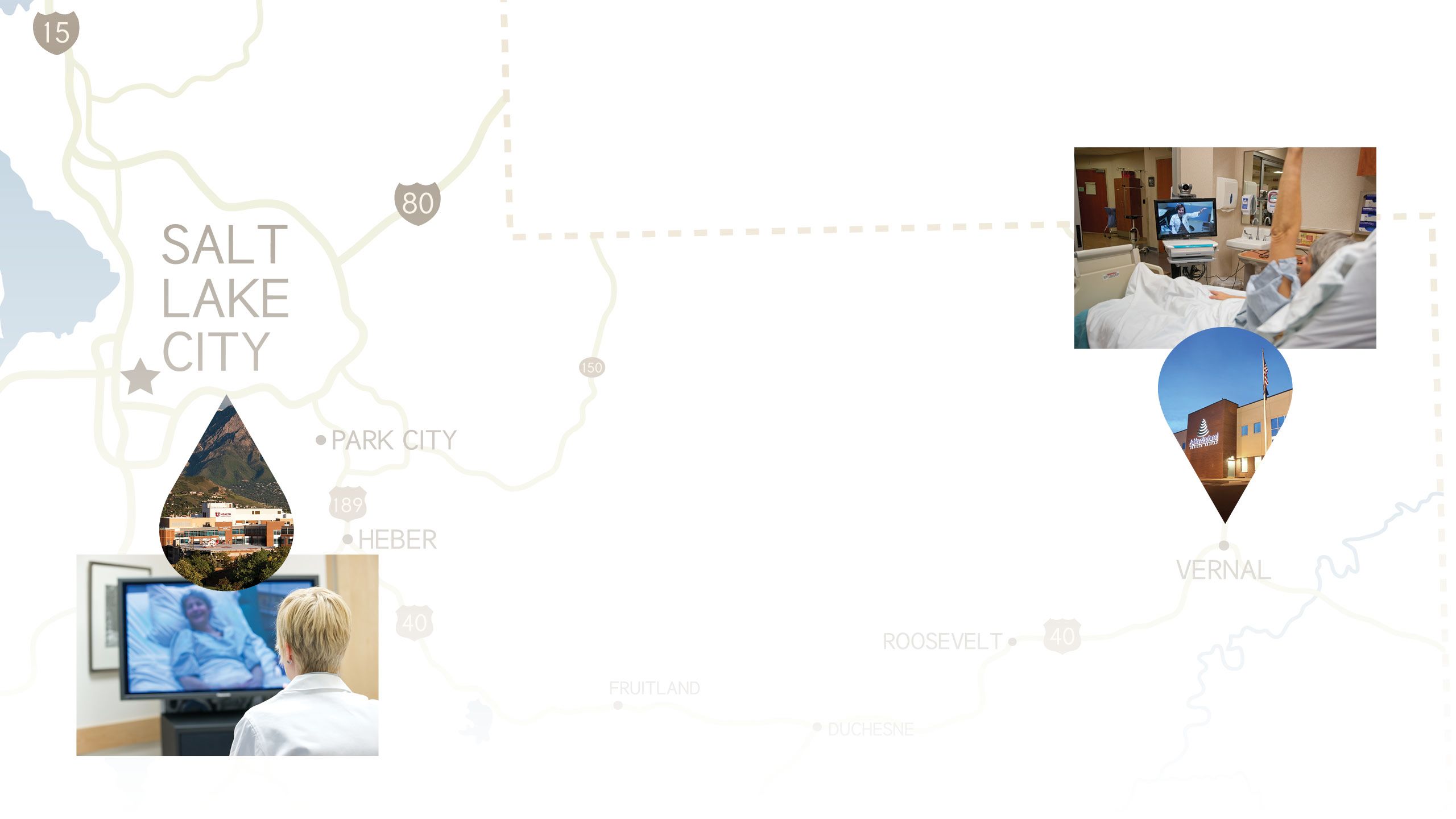

That’s why telehealth services that connect providers in remote locations to a broad range of specialists, ICU, or critical care doctors at University of Utah Health can be so important. “Telemedicine allows us to extend our expertise to rural communities and reduce that sense of isolation that providers can feel,” says Nate Gladwell, RN, MHA, senior director of operations at U of U Health.

U of U Health Telehealth Services works with more than 80 regional locations. One such partner is Vernal’s Ashley Regional Medical Center, which serves northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado. Ashley’s 24-hour-a-day ER treats more than 14,000 patients a year. “We have good doctors here and the capabilities to take care of patients,” says Cesar Garcia, nursing and ICU services director. But compared to a large Level 1 Trauma Center, hospitals like Ashley don’t have 24/7 resources and multi-specialty expertise.

For example, at 3 am on a recent morning, an Ashley Regional nurse was struggling to understand a patient’s EKG. She didn’t recognize what resembled a reverse tick or hockey stick and didn’t want to wake the doctor. So she video-consulted U of U Health’s ICU charge nurse in SLC, who helped her treat the patient by diagnosing a potentially lethal toxicity of the heart drug digoxin. When a young mother losing her eyesight arrived at the Portneuf Medical Center emergency department in Pocatello, Idaho, a TeleNeurology consultation helped diagnose a rare condition and recommended treatment, which she still receives without having to leave her hometown.

“Offering on-demand access to providers is by no means on the fringe of what we do,” says Tad Morley, MHA, FACHE, vice president of outreach and network development. “Empowering clinicians to provide world-class care for patients, right where they live, is at the core of what U of U Health is all about.”

THE FUTURE IS NOW

TELEHEALTH EXPANDS ACCESS FOR RURAL RESIDENTS

Through programs like Telehealth Services and Project ECHO, specialists in Salt Lake City can conference with providers in rural locations such as Ashley Regional Medical Center in Vernal, allowing patients to receive timely, sometimes life-saving care right where they live. Photos Courtesy of Ashley Regional Medical Center and University of Utah Health

Through programs like Telehealth Services and Project ECHO, specialists in Salt Lake City can conference with providers in rural locations such as Ashley Regional Medical Center in Vernal, allowing patients to receive timely, sometimes life-saving care right where they live. Photos Courtesy of Ashley Regional Medical Center and University of Utah Health

Picture a small ER in a rural county hospital. A patient has had a stroke. If the sole physician on duty administers a drug called tPA within a narrow window of time, chances are the patient will make a nearly complete recovery. If the physician has to transfer that patient to a larger facility for care, that small treatment window will close and doctors can often do nothing.

That’s why telehealth services that connect providers in remote locations to a broad range of specialists, ICU, or critical care doctors at University of Utah Health can be so important. “Telemedicine allows us to extend our expertise to rural communities and reduce that sense of isolation that providers can feel,” says Nate Gladwell, RN, MHA, senior director of operations at U of U Health.

U of U Health Telehealth Services works with more than 80 regional locations. One such partner is Vernal’s Ashley Regional Medical Center, which serves northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado. Ashley’s 24-hour-a-day ER treats more than 14,000 patients a year. “We have good doctors here and the capabilities to take care of patients,” says Cesar Garcia, nursing and ICU services director. But compared to a large Level 1 Trauma Center, hospitals like Ashley don’t have 24/7 resources and multi-specialty expertise.

For example, at 3 am on a recent morning, an Ashley Regional nurse was struggling to understand a patient’s EKG. She didn’t recognize what resembled a reverse tick or hockey stick and didn’t want to wake the doctor. So she video-consulted U of U Health’s ICU charge nurse in SLC, who helped her treat the patient by diagnosing a potentially lethal toxicity of the heart drug digoxin. When a young mother losing her eyesight arrived at the Portneuf Medical Center emergency department in Pocatello, Idaho, a TeleNeurology consultation helped diagnose a rare condition and recommended treatment, which she still receives without having to leave her hometown.

“Offering on-demand access to providers is by no means on the fringe of what we do,” says Tad Morley, MHA, FACHE, vice president of outreach and network development. “Empowering clinicians to provide world-class care for patients, right where they live, is at the core of what U of U Health is all about.”

SAVING LIVES WITH TECHNOLOGY

University of Utah

Health offers

59

telehealth programs in

83

partner facilities

throughout Utah, Nevada,

Idaho, Montana, Wyoming,

and Colorado

9,400+

Patient encounters in FY19

(45% increase over FY18)

Project ECHO

Multi-disciplinary

specialist teams, who use

videoconferencing to train

community providers,

have offered

4,000+

case-based learning

lessons on 13+ health care

topics since 2011

In 2019,

570+

providers throughout the

Mountain West participated

in Project ECHO trainings

Other rural outreach projects include the Coal Country Strike Team, which in the future aims to increase workforce options for residents of Carbon and Emery Counties. Photo by Malcolm Howard

Other rural outreach projects include the Coal Country Strike Team, which in the future aims to increase workforce options for residents of Carbon and Emery Counties. Photo by Malcolm Howard

“Expanding Access, Education, and Jobs to All Corners of the State”

Words by Nick McGregor with Stephen Dark

Design by:

Jesse Colby

Extra thanks to

Nafisa Masud, Anna Cekola, and the Moran Eye Center