RECOVERED FROM COVID-19 BUT WITH AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

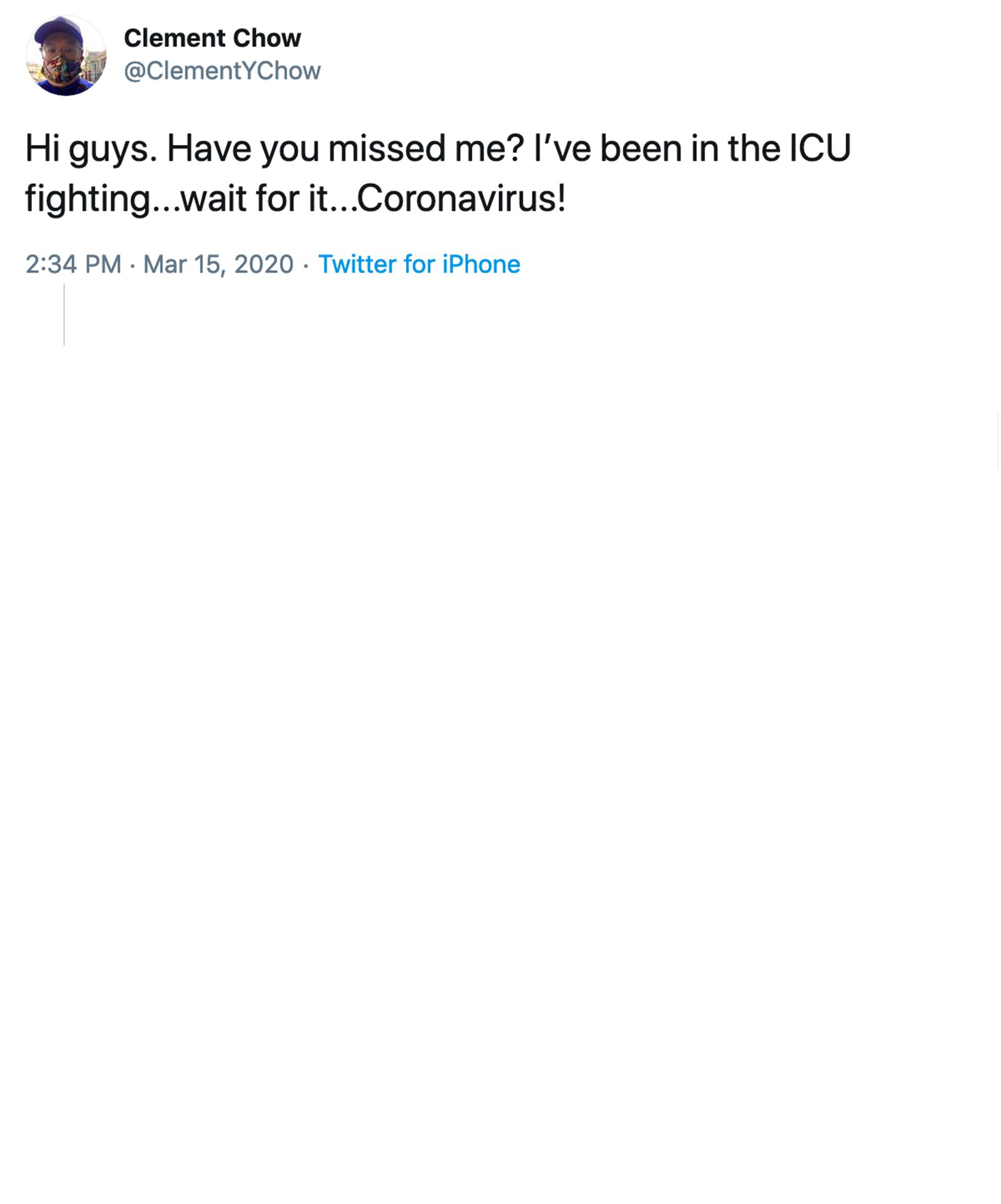

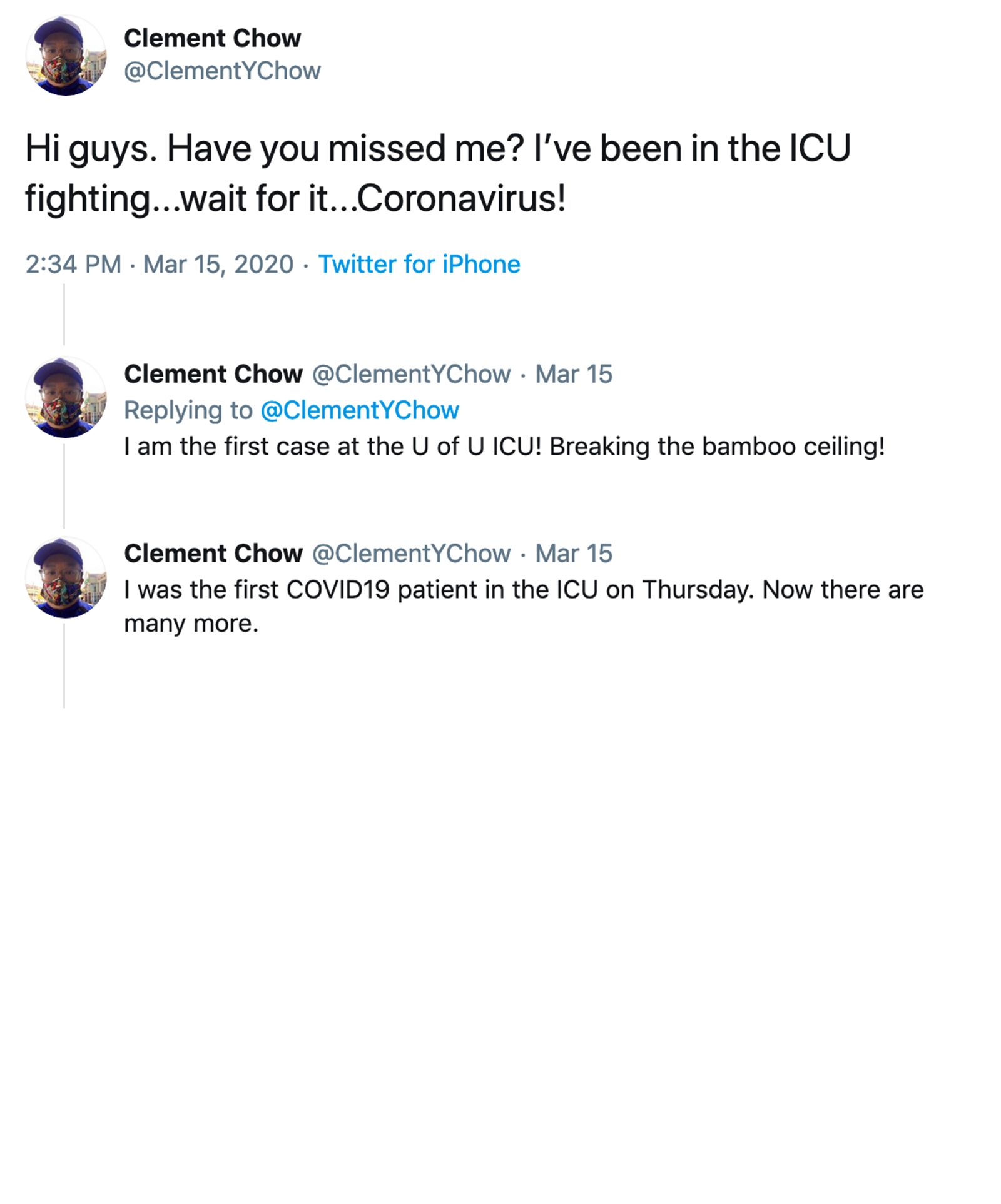

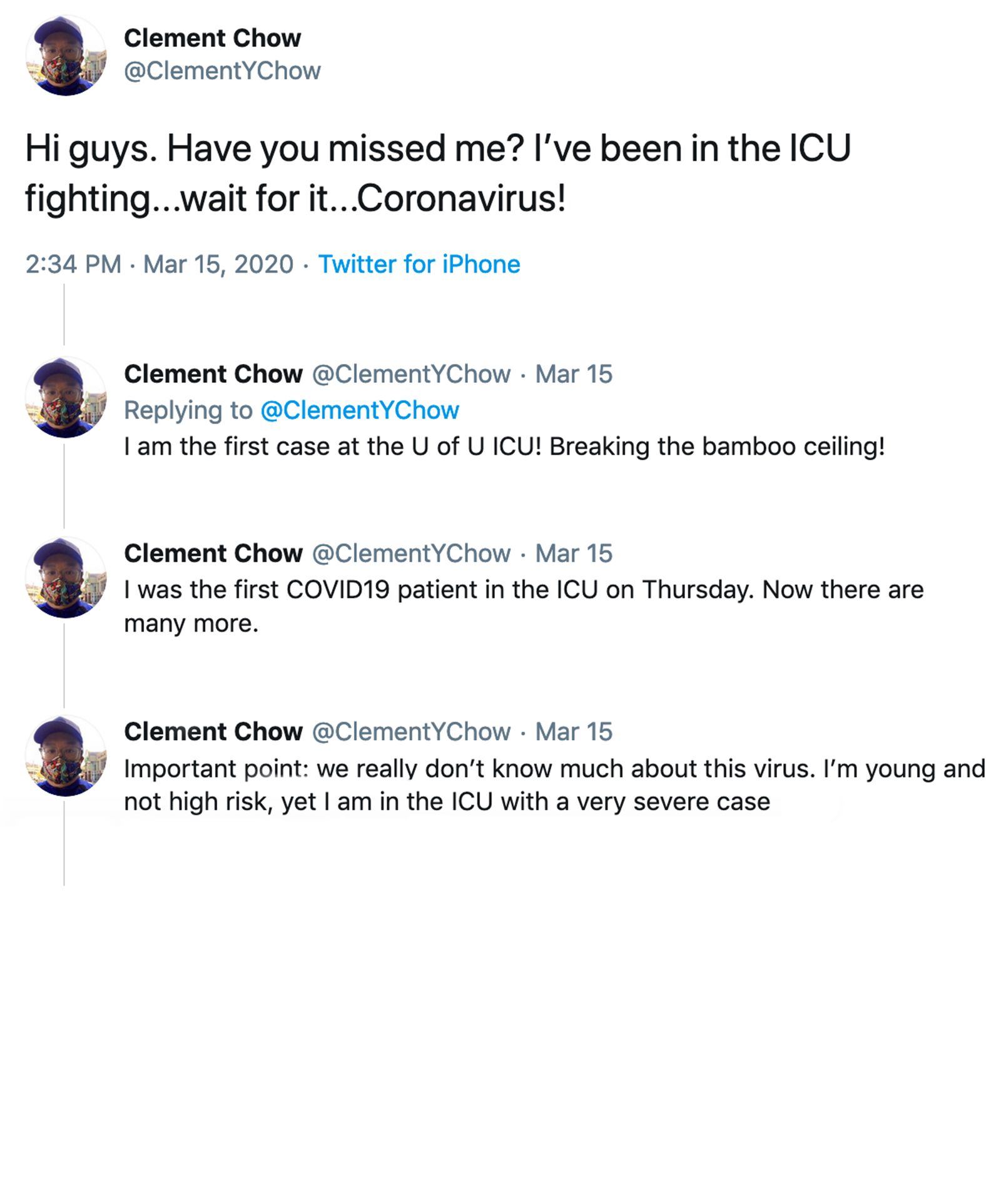

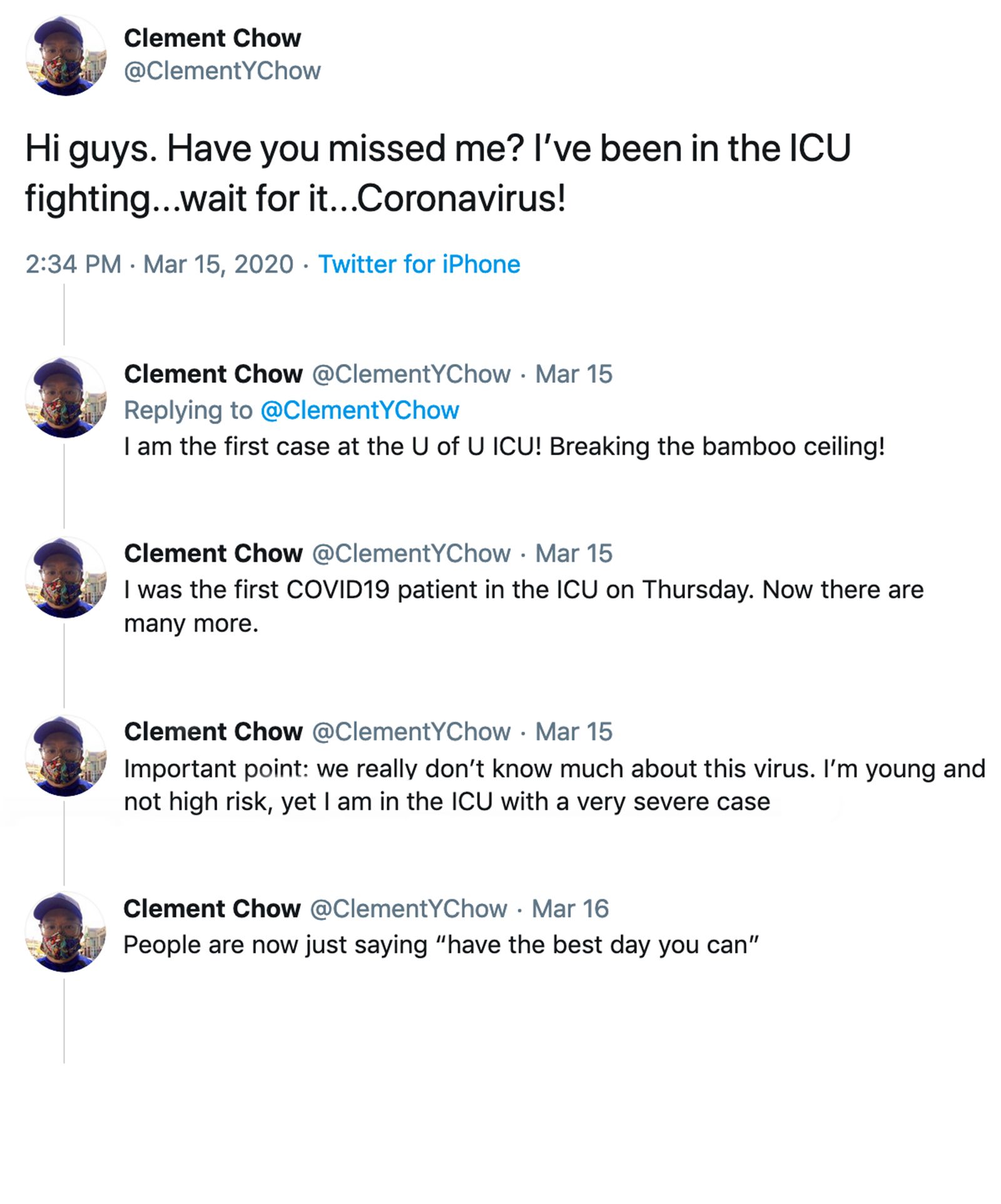

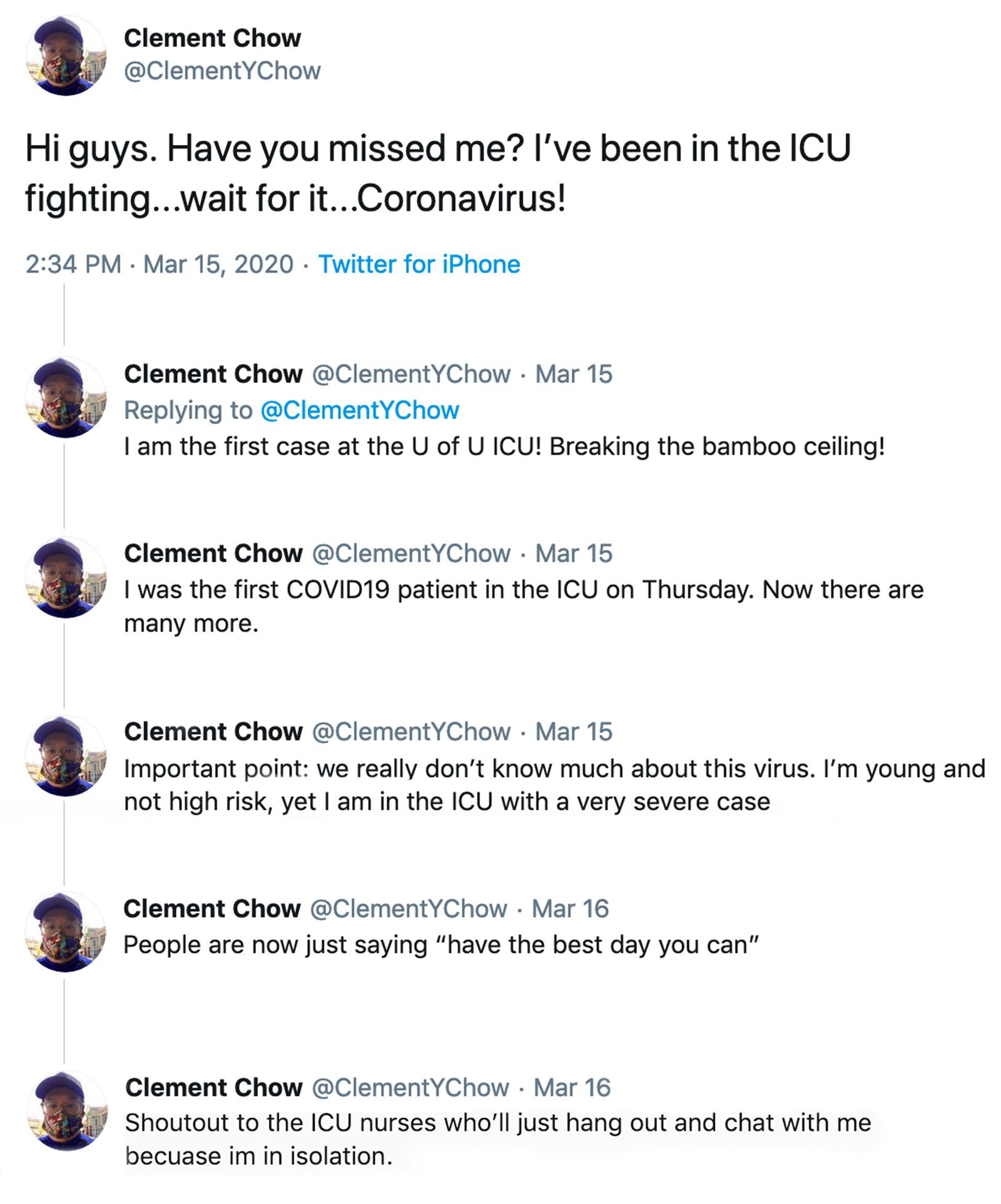

On March 13, Clement Chow found himself on the leading edge of a tidal wave. He was at University of Utah Hospital as one of the first COVID-19 cases in the state, and amongst the most severely ill.

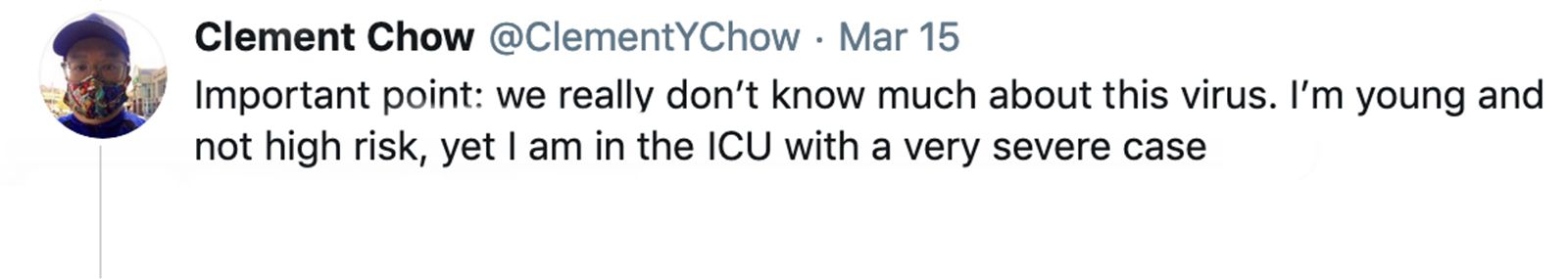

“I will fight COVID-19 with information,” he typed into Twitter from his hospital bed.

It was an apt declaration for the U of U Health assistant professor of human genetics, whose job it is to seek truths and share them widely. In response, his social media feed swelled by 13,000 new followers overnight. People across the globe were hungry to hear about the emerging disease from someone who was living it.

Even now—seven months after COVID-19 first entered our world and four months after Chow returned home from the hospital—our understanding of the disease and its long-term effects is still in its infancy. Each infection, hospitalization, death and recovery reveal new details, and progressively we piece them into a story. With each telling, we hope to learn more about the disease and protecting one another.

“Like Nothing I’ve Ever Seen.”

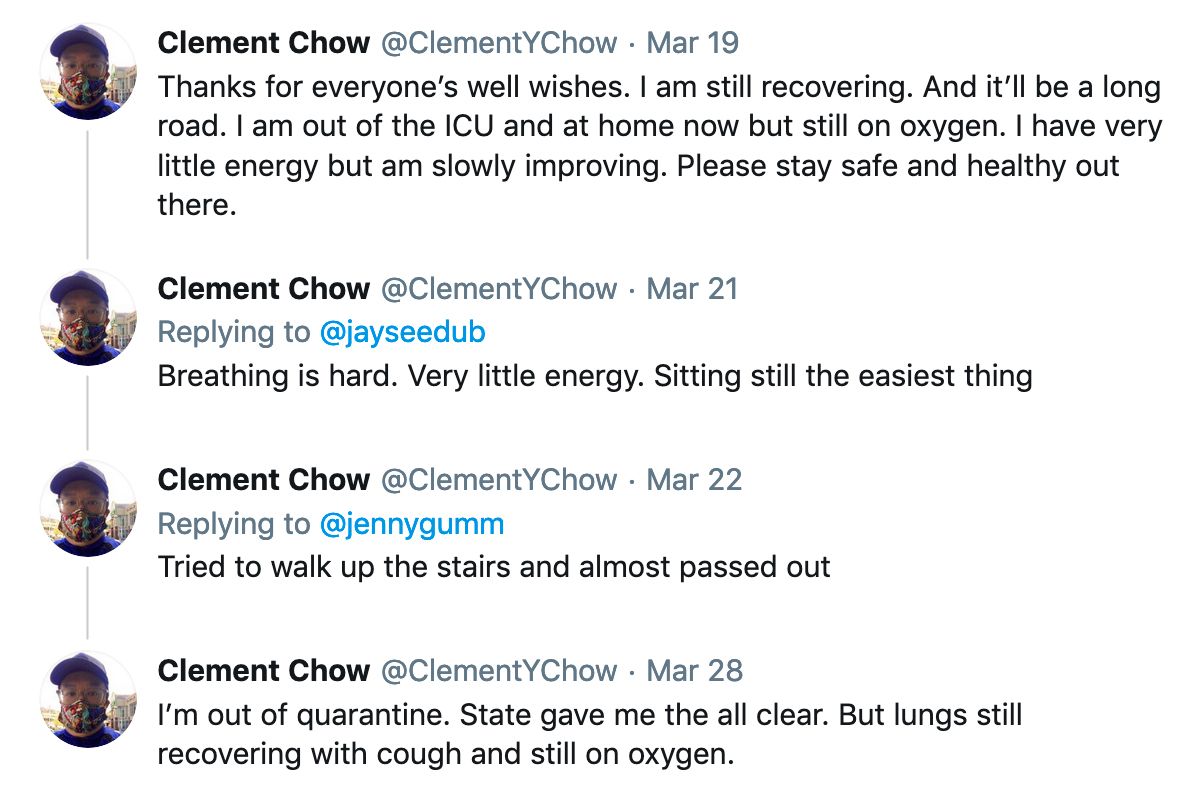

By broadcasting his journey on social media, Chow had hoped to make the best of a bad situation. But it didn’t take long before his tweets became shorter and the time between them longer. His fight against the illness had become more grueling than he ever anticipated.

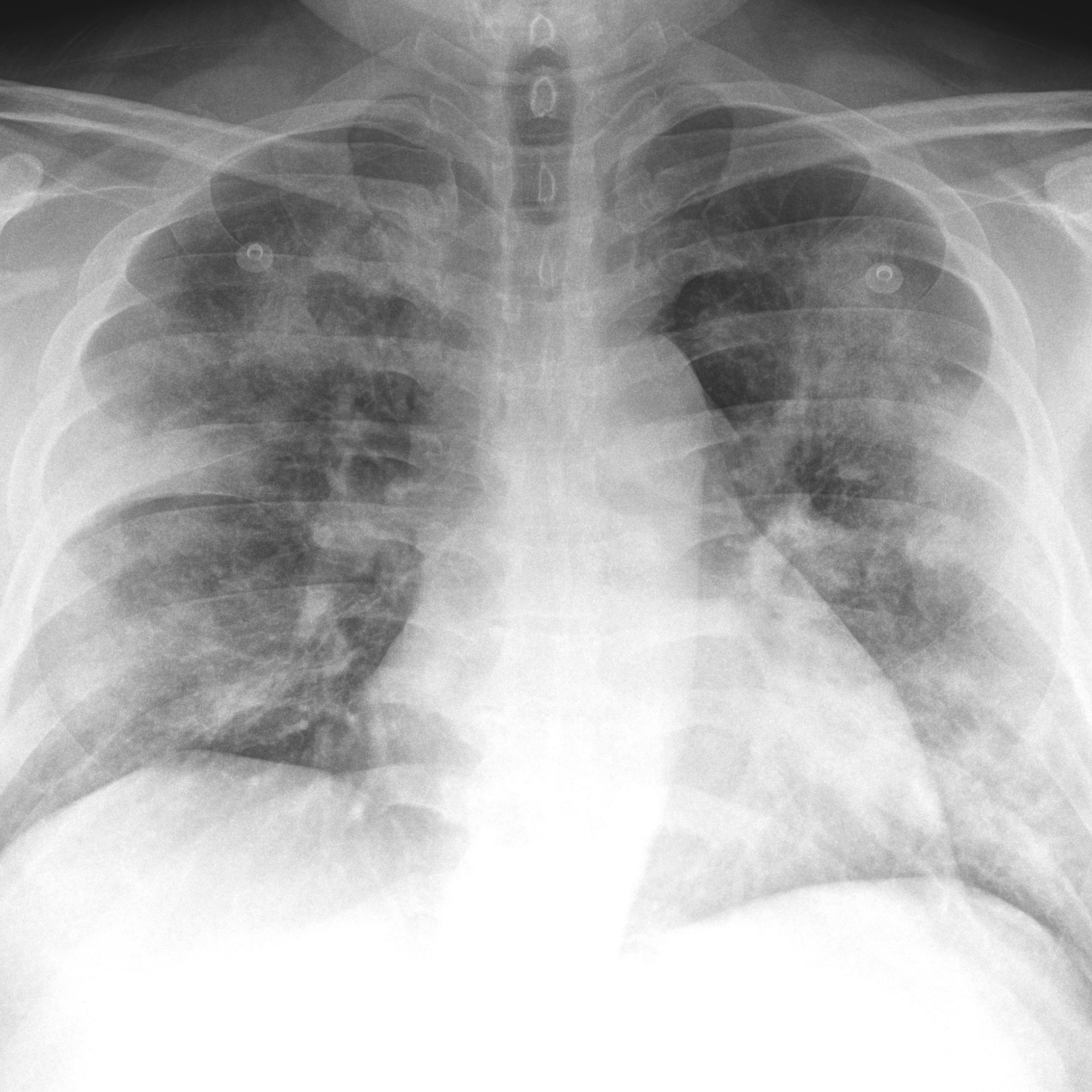

Twenty-four hours earlier, the idea that he could have COVID-19 hadn’t crossed his mind. He had a terrible cough but figured he was sick with a run-of-the-mill illness his kids had brought home from school. A physician friend he had been in touch with, however, grew concerned. At his urging, Chow took stock of the situation with a pulse oximeter, a small, inexpensive medical device he happened to have at home. After attaching it to his finger to measure his blood oxygen, the screen blinked “70%”—dangerously lower than the 85% reading that warrants a trip to the hospital.

“I can barely remember that day,” Chow says, now suspecting his brain had been foggy from being oxygen deprived. The symptom may have prevented him from seeking help sooner.

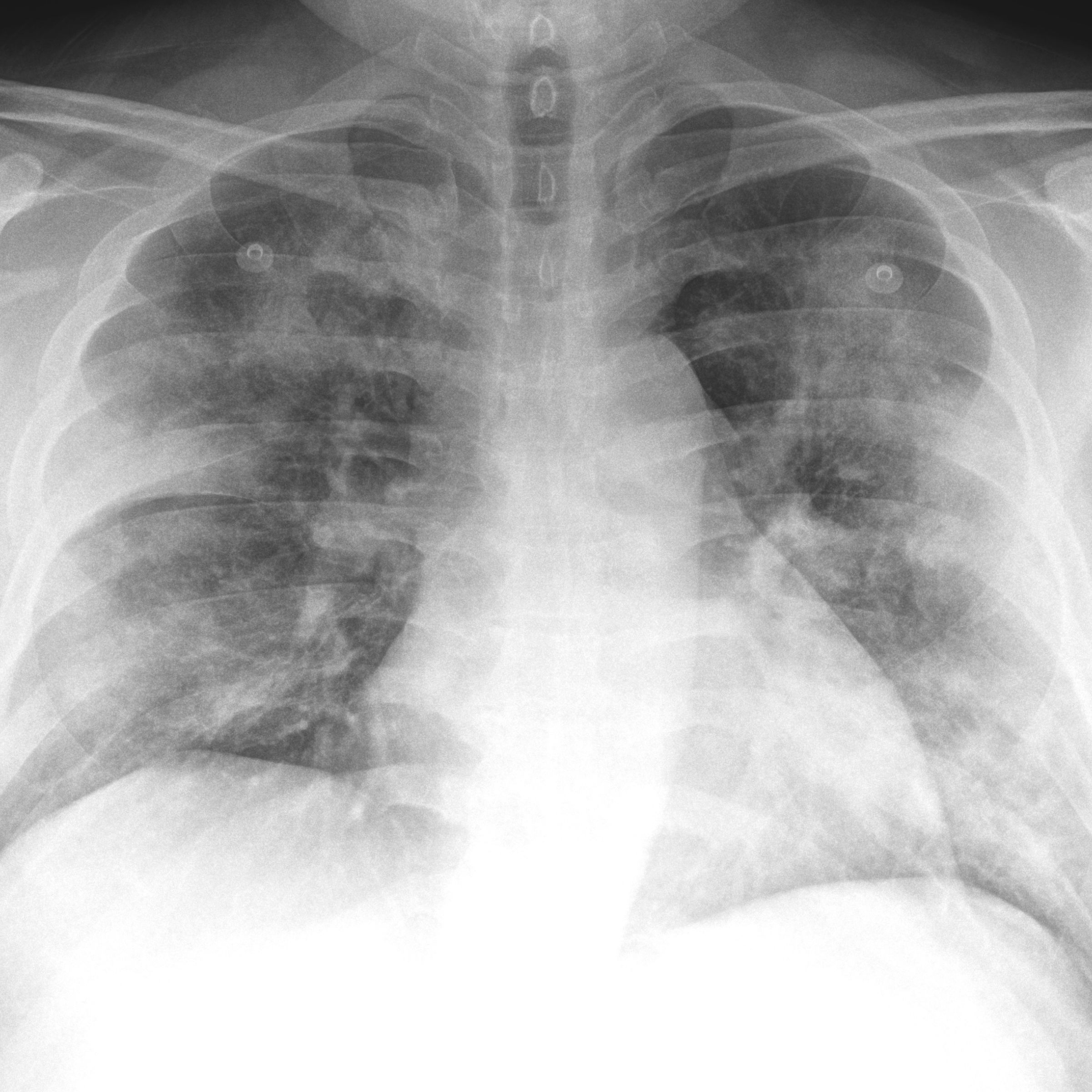

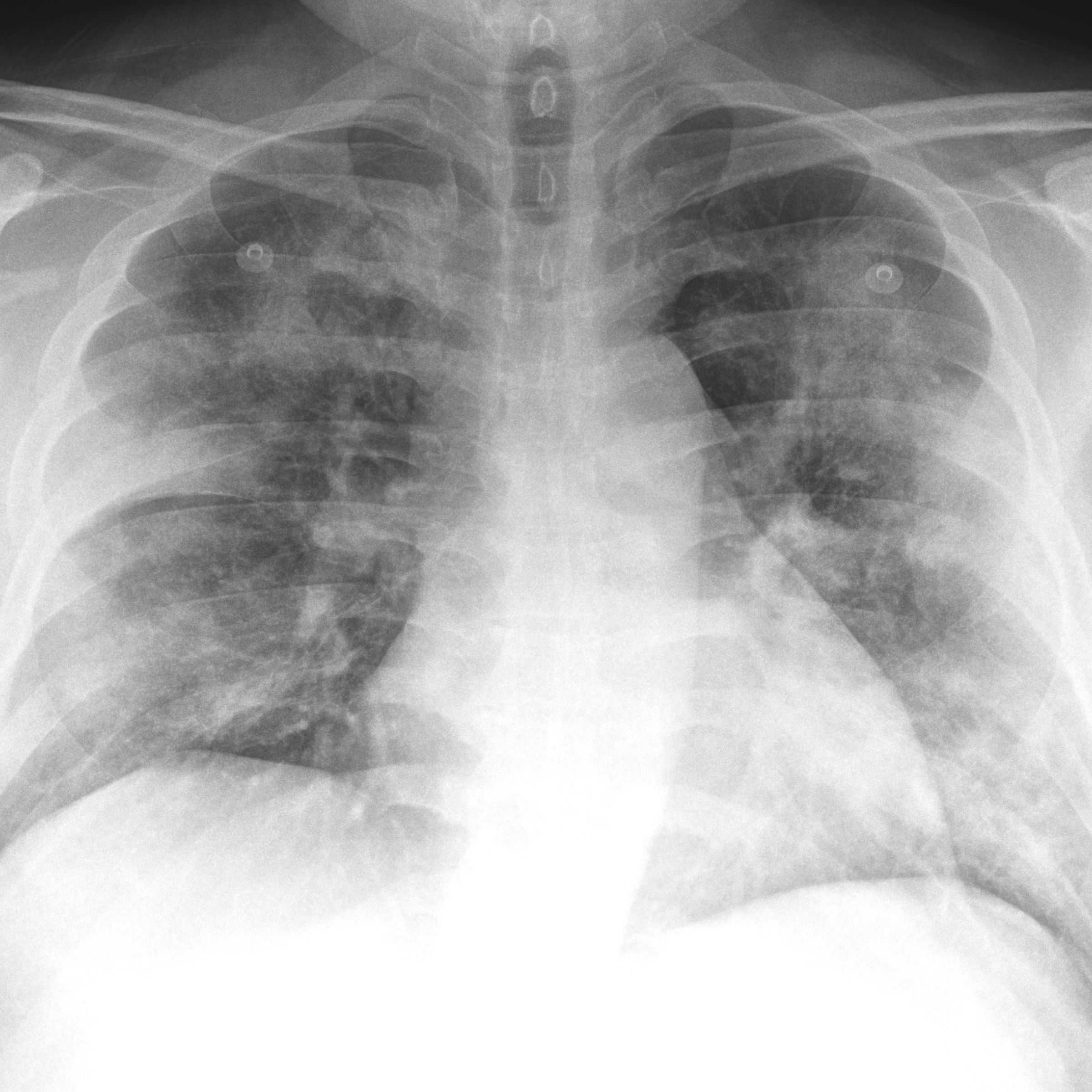

His wife rushed him to the emergency department (ED) but despite receiving supplemental oxygen, he was still gasping for air. Within hours, doctors transferred him to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) where they could monitor him more closely. There, a high-flow machine pushed oxygen into his body at up to 12 times the rate he was given in the ED. Only then did he feel relief.

“I could literally feel the oxygen flowing through to my extremities,” Chow says. “I thought, ‘This is what breathing feels like.’”

With symptoms ranging from nonexistent (asymptomatic) to deadly, perhaps one of the most puzzling aspects of COVID-19 is the unpredictability of how the disease unfolds for each person. As a father with two young children, Chow doesn’t fit the stereotype of the nearly 10% of infected people who need hospitalization. He is at least 27 years younger than the age group at highest risk and doesn’t have any of the long list of medical conditions that could shift a lower-risk person into a more vulnerable category.

Researchers at U of U Health are investigating whether genetics or drug interactions could play a role, or if they can uncover unique susceptibilities. In time, such information could more precisely pinpoint who is prone to complications.

As a hospitalist at U of U Health, Natalie Como, MD, has encountered a lot of viral infections. But she says COVID-19 is “like nothing I’ve ever seen.” What’s particularly striking to her is how ill COVID-19 can make otherwise healthy, active people. And once it grabs hold, it doesn’t let go.

“A pattern we’re seeing is that when people hit their worst respiratory point, they stay there a long time,” Como says.

Typically, ICU patients remain in that wing of the hospital for three days on average. In contrast, the average ICU stay for COVID-19 patients at U of U Health is 10 days; a rare few have needed intensive care for months.

Besides providing oxygen, either through a high-flow device like Chow had or through a more invasive breathing machine—the ventilator—there is not much that health care providers can do to speed recovery.

By broadcasting his journey on social media, Chow had hoped to make the best of a bad situation. But it didn’t take long before his tweets became shorter and the time between them longer. His fight against the illness had become more grueling than he ever anticipated.

Twenty-four hours earlier, the idea that he could have COVID-19 hadn’t crossed his mind. He had a terrible cough but figured he was sick with a run-of-the-mill illness his kids had brought home from school. A physician-friend he had been in touch with, however, grew concerned. At his urging, Chow took stock of the situation with a pulse oximeter, a small, inexpensive medical device he happened to have at home. After attaching it to his finger to measure his blood oxygen, the screen blinked “70%”— dangerously lower than the 85% reading that warrants a trip to the hospital.

“I can barely remember that day,” Chow says, now suspecting his brain had been foggy from being oxygen deprived. The symptom may have prevented him from seeking help sooner.

His wife rushed him to the emergency department (ED) but despite receiving supplemental oxygen, he was still gasping for air. Within hours, doctors transferred him to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) where they could monitor him more closely. There, a high-flow machine pushed oxygen into his body at up to 12 times the rate he was given in the ED. Only then did he feel relief.

“I could literally feel the oxygen flowing through to my extremities,” Chow says. “I thought, ‘This is what breathing feels like.’”

With symptoms ranging from nonexistent (asymptomatic) to deadly, perhaps one of the most puzzling aspects of COVID-19 is the unpredictability of how the disease unfolds for each person. As a father with two young children, Chow doesn’t fit the stereotype of the nearly 10% of infected people who need hospitalization. He is at least 27 years younger than the age group at highest risk and doesn’t have any of the long list of medical conditions that could shift a lower-risk person into a more vulnerable category.

Researchers at U of U Health are investigating whether genetics or drug interactions could play a role, or if they can uncover unique susceptibilities. In time, such information could more precisely pinpoint who is prone to complications.

As a hospitalist at U of U Health, Natalie Como, MD, has encountered a lot of viral infections. But she says COVID-19 is “like nothing I’ve ever seen.” What’s particularly striking to her is how ill COVID-19 can make otherwise healthy, active people. And once it grabs hold, it doesn’t let go.

“A pattern we’re seeing is that when people hit their worst respiratory point, they stay there a long time,” says Como.

Typically, ICU patients remain in that wing of the hospital for three days on average. In contrast, the average ICU stay for COVID-19 patients at U of U Health is 10 days, a rare few have needed intensive care for months.

Besides providing oxygen, either through a high-flow device like Chow had or through a more invasive breathing machine—the ventilator—there is not much that health care providers can do to speed recovery.

Only recently, non-ventilated patients have started receiving remdesivir, a drug shown to have mild benefits. Some patients are given convalescent plasma from recovered patients, the effects of which are still the subject of investigation. Clinical trials at U of U Health are evaluating the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine in study participants who are well enough to weather the illness at home. Another trial is examining a novel approach: whether human amniotic fluid—known to dampen harmful inflammation—reduces disease severity.

Over time, the data will shake out the benefits and risks of each. Until then, doctors and nurses continue to fight for patients’ lives with the best tools currently available and providing supportive care while they wait for the disease to turn around.

“You end up writing the same notes every day over and over: ‘Mrs. X looks the exact same as she has for the past seven days,’” says Nathan Hatton, MD, an associate professor of medicine.

As patients linger, there is the constant worry that any number of complications could develop, or that someone could suddenly die. “It’s fatiguing for everyone,” Hatton says.

Compounding the fatigue is anxiety fueled by a general lack of understanding about the disease. The uneasy feeling was especially palpable during the time when Chow came to the hospital, as the pandemic was first creeping into Utah’s borders. Health care providers were left guessing about what to do and hoping they were giving the best care they could.

“Patients would ask, ‘What’s going to happen? Am I going to get better?’” Como says. “The best answer we could give was, ‘I don’t know but whatever happens we’ll be here for you.’ As a doctor, you always want to know. It’s hard.”

The Battle Inside

Chow remained “stuck” on a dangerous plateau, relying on high-flow oxygen for days. But for him—and for the sickest patients who remain on a ventilator for days or weeks—that seemingly stagnant phase masks a dynamic battle happening inside.

A desire to improve the prospects of her patients drives critical care physician Elizabeth Middleton, MD, to carry out research that sees the unseen. “Caring for these patients opens up all kinds of questions about what is going on mechanistically and how we can improve outcomes with targeted therapies,” she says.

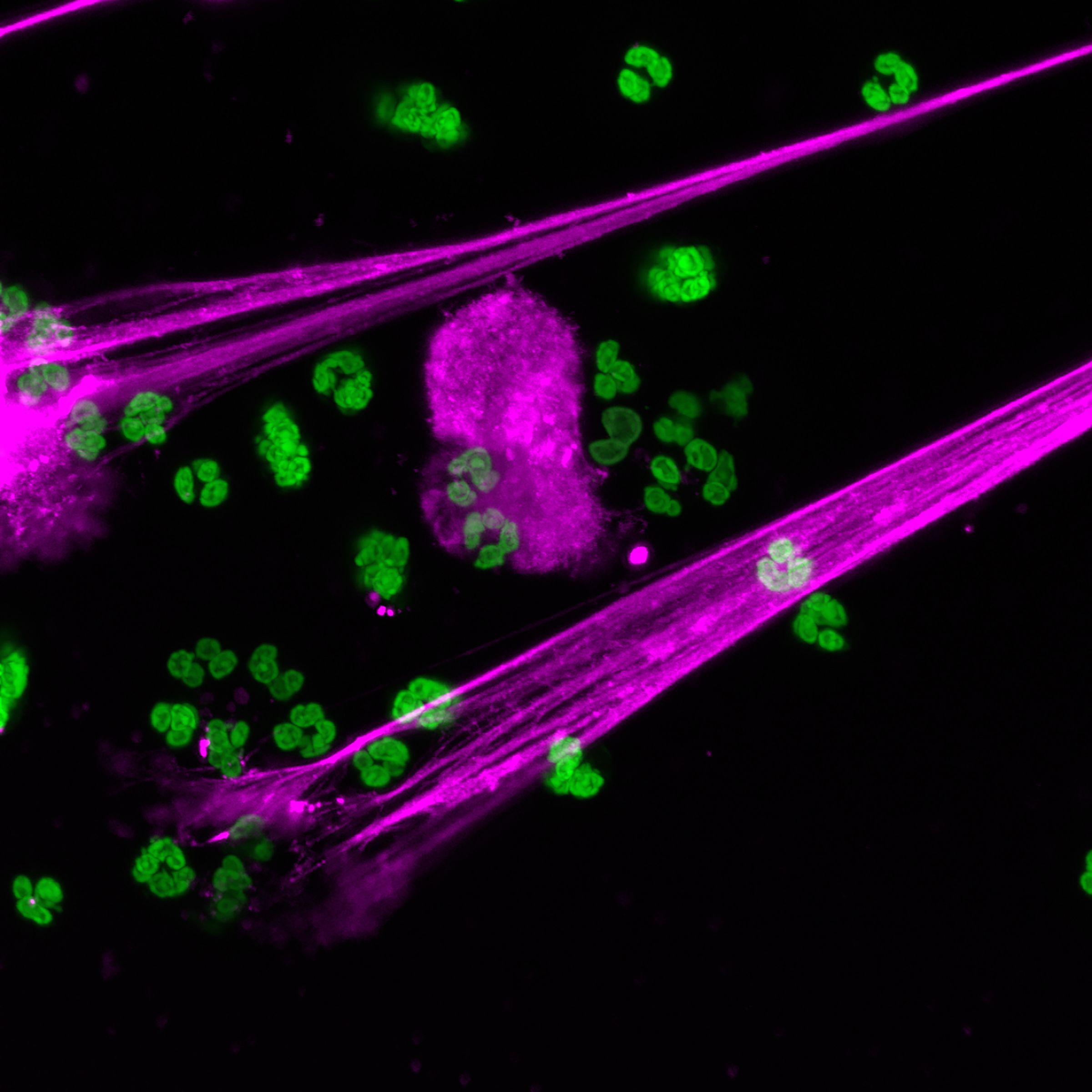

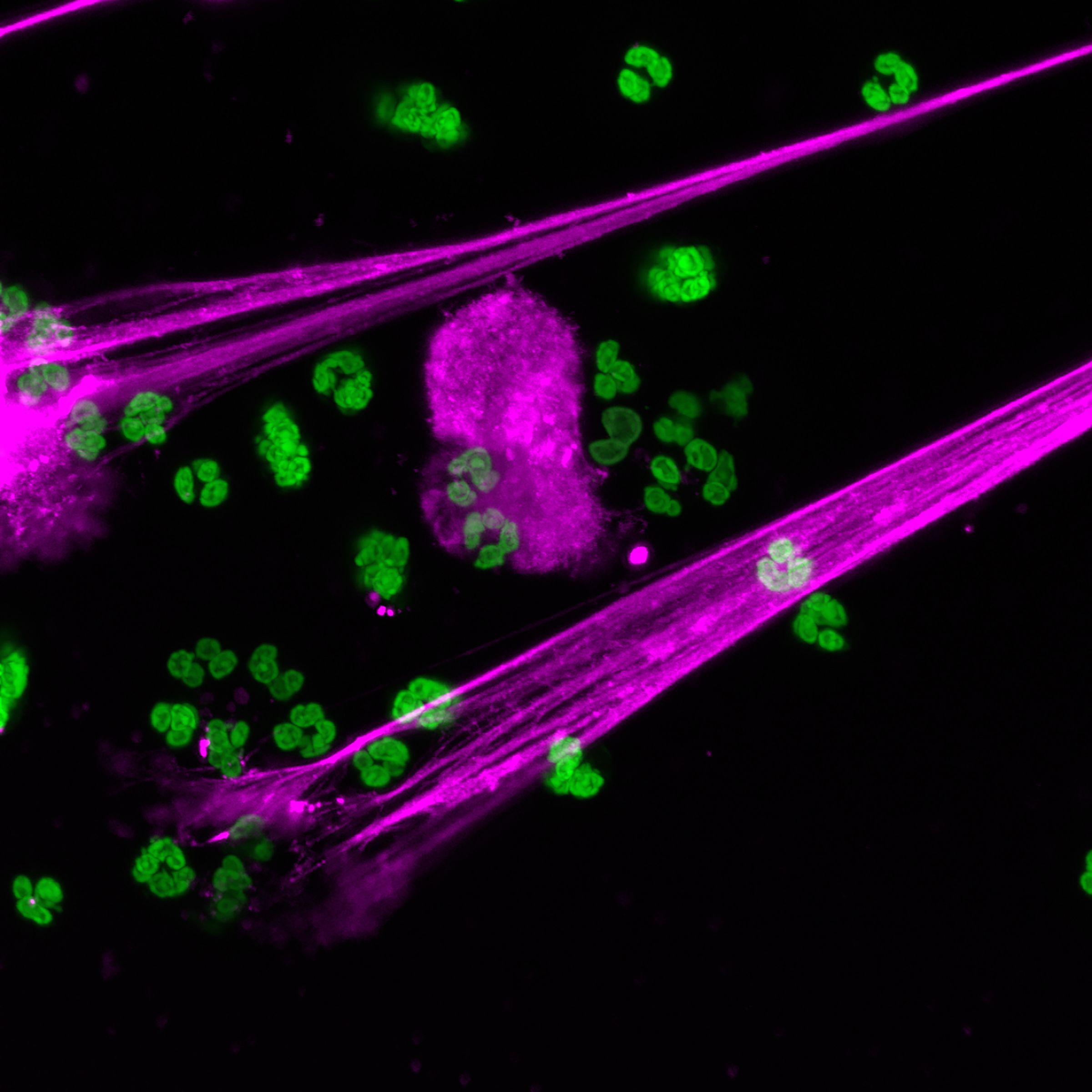

Together with U of U Health physician-scientists Christian Con Yost, MD, and Joshua Schiffman, MD, their team discovered that an out-of-control immune response could be causing complications. Ordinarily web-like NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) are beneficial, capturing and killing invading pathogens like viruses. But in COVID-19, the mechanism becomes hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting, potentially leading to organ failure in the worst cases.

“This could be a brand-new area of pathobiology that could shed a light on COVID-19 morbidity and mortality,” Schiffman says. Experiments in the lab show that a peptide from umbilical cord blood quiets the highly active immune response. In his role as CEO of PEEL Therapeutics, Schiffman is now evaluating whether the natural chemical can one day be used as a therapy for patients.

Their colleagues in internal medicine led by Robert Campbell, PhD, also called upon Middleton. That collaboration led to the discovery that multiple genetic changes in circulating cells, called platelets, may also contribute to an abnormal inflammatory response and worsening COVID-19.

These findings are the tip of the iceberg. Some patients also sustain damage to the heart, gastrointestinal system, kidneys, and liver; there are reports of stroke and seizures. At this point it is hard to parse whether these impacts come from uncontrolled inflammation or are a direct effect of the virus.

Even treatment itself has downsides. While the ventilator undoubtedly saves the lives of people who are severely ill with COVID-19, extended use of sedatives that allow patients to tolerate a tube lodged in their airway can cause delirium and memory loss that persist after recovery. Plus, the longer someone is immobilized, the more that muscles waste away, vessels clot and eventually organs malfunction. With COVID-19 patients lingering on ventilators, lasting side effects are a concern.

“The physical and mental toll is not small,” says pulmonologist Scott Aberegg, MD, who has treated patients with the disease in Utah and during the surge in New York City in April. There, he saw patients emerging from the ICU barely able to string a sentence together. “Only time will tell what the long-term effects will be.”

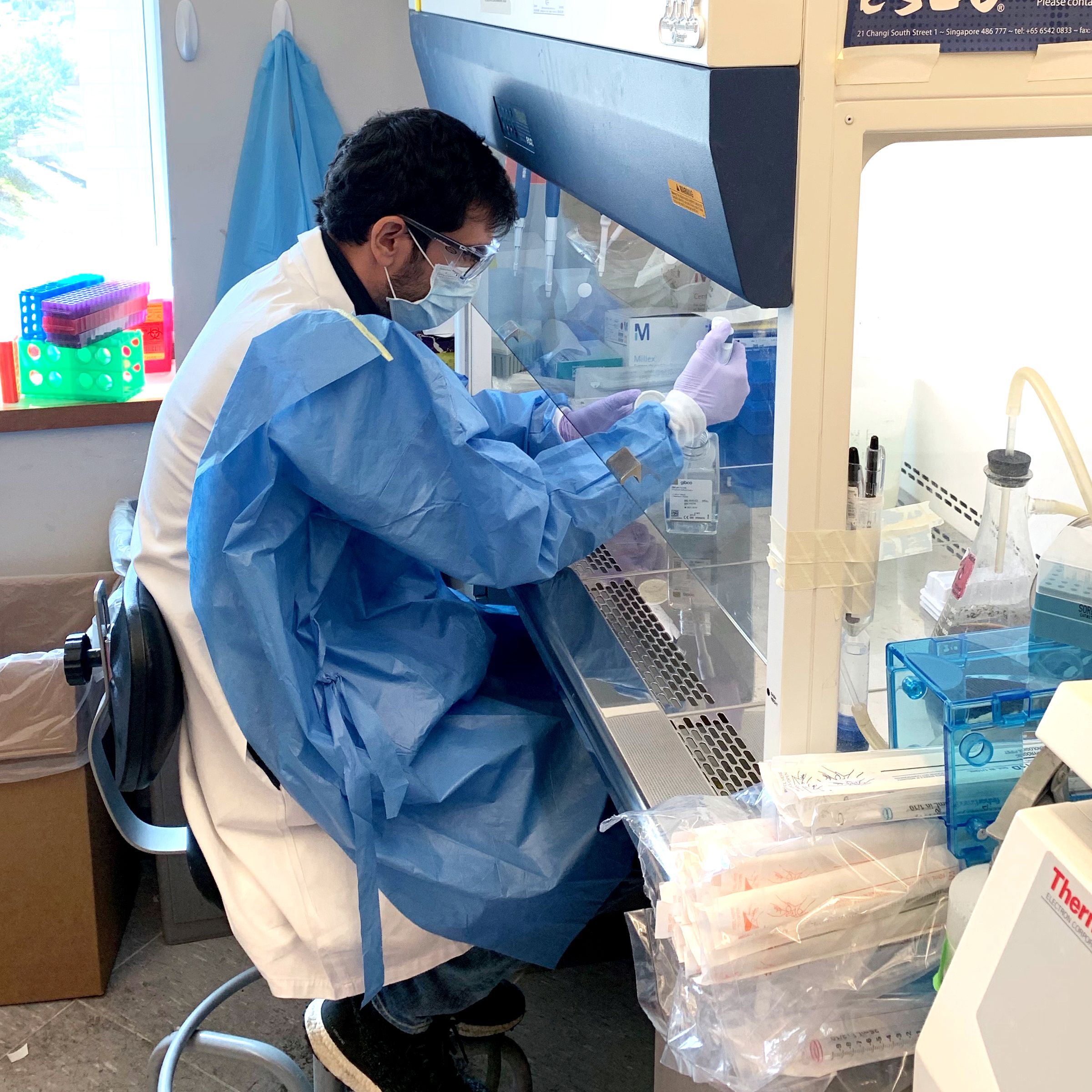

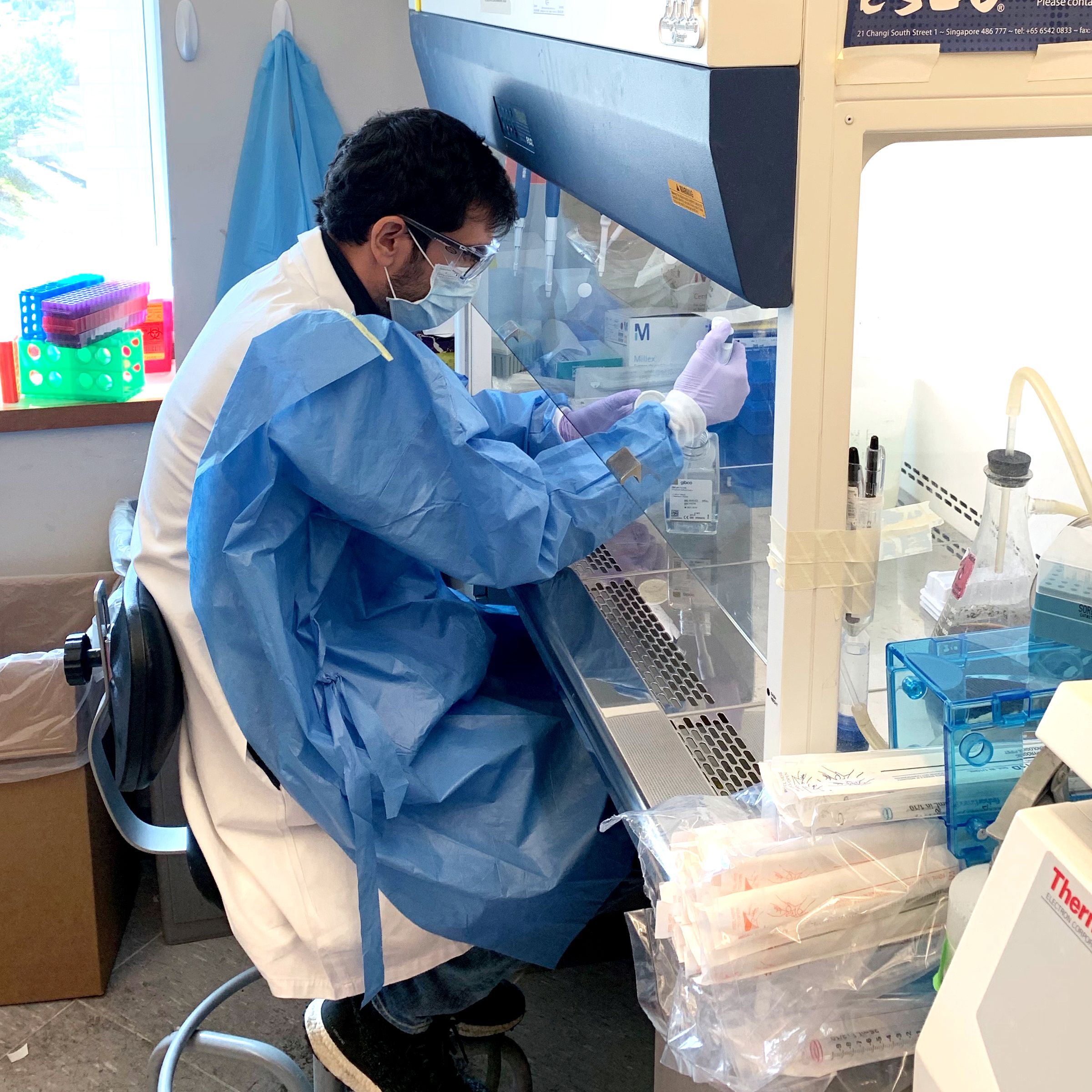

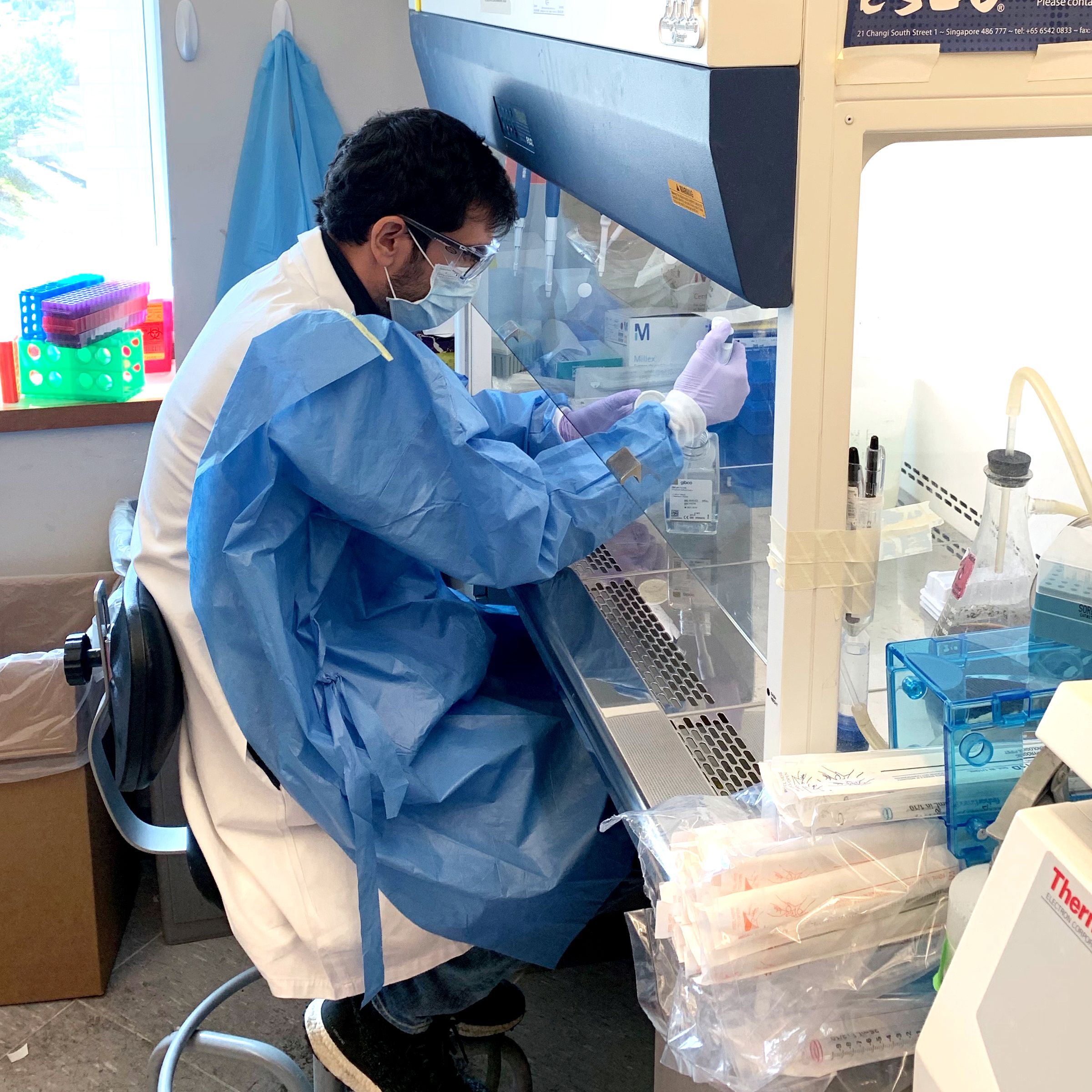

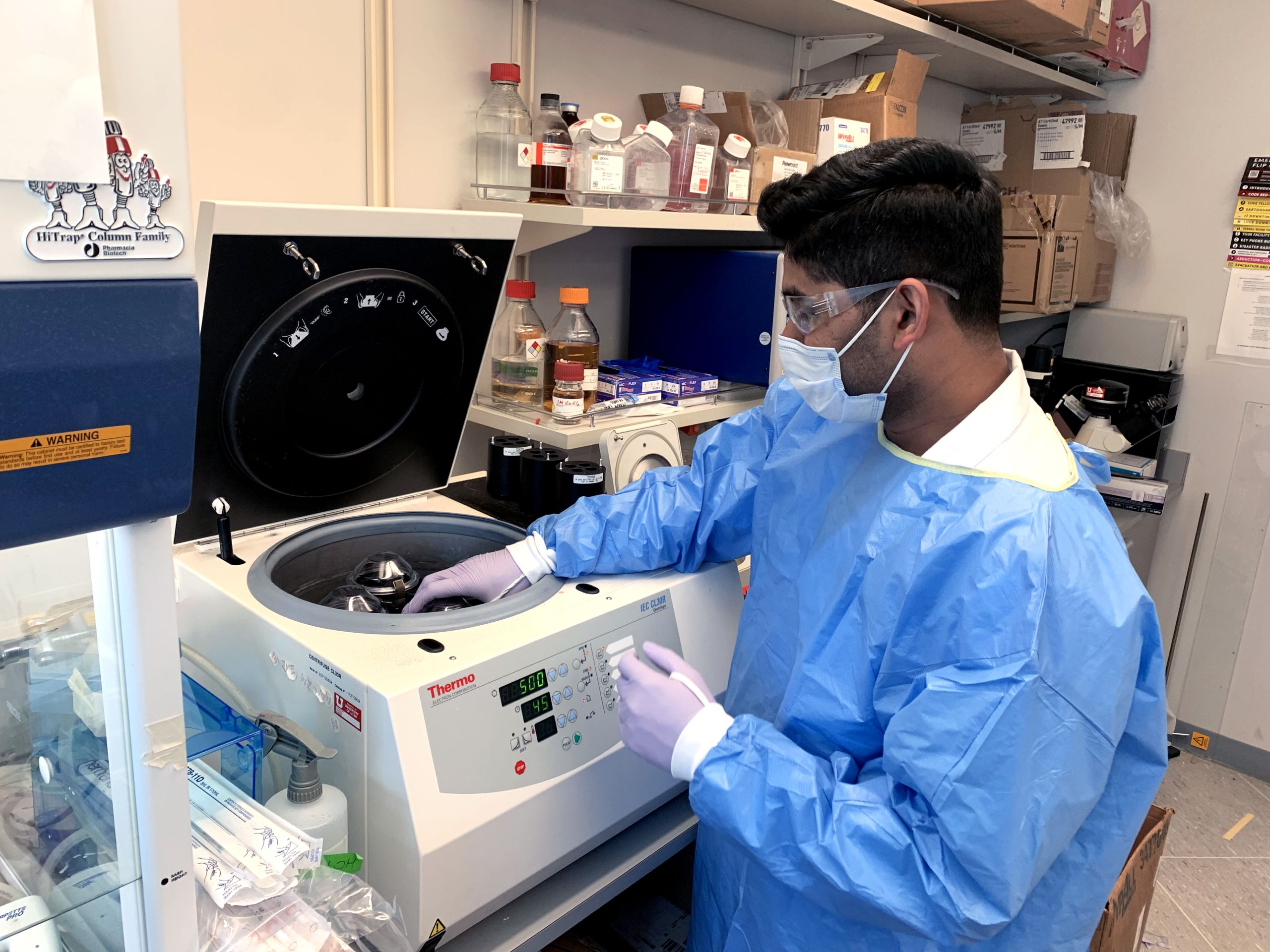

Researcher Frederik Denorme, PhD, investigates causes of complications that occur in the worst cases of COVID-19.

Researcher Frederik Denorme, PhD, investigates causes of complications that occur in the worst cases of COVID-19.

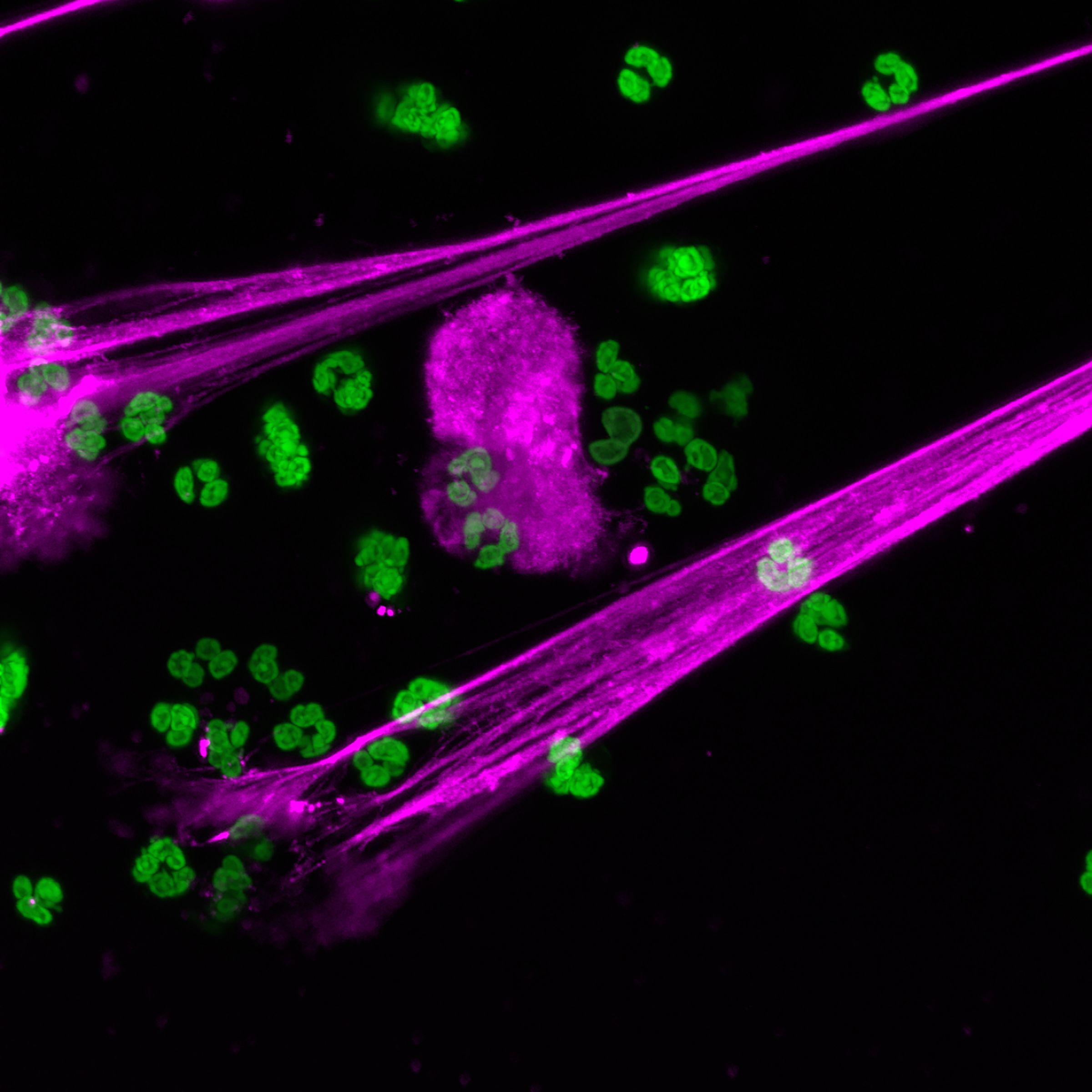

In patients with severe COVID-19, NETs become hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting that leads to organ failure.

In severe COVID-19, NETs become hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting, leading to organ failure and other complications.

NETs tell us about a potential mechanism for lung injury in COVID-19.

NETs tell us about a potential mechanism for lung injury in COVID-19.

Chow remained “stuck” on a dangerous plateau, relying on high-flow oxygen for days. But for him—and for the sickest patients who remain on a ventilator for days or weeks—that seemingly stagnant phase masks a dynamic battle happening inside.

A desire to improve the prospects of her patients drives critical care physician Elizabeth Middleton, MD, to carry out research that sees the unseen. “Caring for these patients opens up all kinds of questions about what is going on mechanistically and how we can improve outcomes with targeted therapies,” she says.

Together with U of U Health physician-scientists Christian Con Yost, MD, and Joshua Schiffman, MD, their team discovered that an out-of-control immune response could be causing complications. Ordinarily web-like NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) are beneficial, capturing and killing invading pathogens like viruses. But in COVID-19, the mechanism becomes hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting, potentially leading to organ failure in the worst cases.

Researcher Frederik Denorme, PhD, investigates causes of complications that occur in the worst cases of COVID-19.

In severe COVID-19, NETs become hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting, leading to organ failure and other complications.

NETs tell us about a potential mechanism for lung injury in COVID-19.

“This could be a brand-new area of pathobiology that could shed a light on COVID-19 morbidity and mortality,” Schiffman says. Experiments in the lab show that a peptide from umbilical cord blood quiets the highly active immune response. In his role as CEO of PEEL Therapeutics, Schiffman is now evaluating whether the natural chemical can one day be used as a therapy for patients.

Their colleagues in internal medicine led by Robert Campbell, PhD, also called upon Middleton. That collaboration led to the discovery that multiple genetic changes in circulating cells, called platelets, may also contribute to an abnormal inflammatory response and worsening COVID-19.

These findings are the tip of the iceberg. Some patients also sustain damage to the heart, gastrointestinal system, kidneys, and liver; there are also reports of stroke and seizures. At this point it is hard to parse whether these injuries come from uncontrolled inflammation or are a direct effect of the virus.

Even treatment itself has downsides. While the ventilator undoubtedly saves the lives of people who are severely ill with COVID-19, extended use of sedatives that allow patients to tolerate a tube lodged in their airway can cause delirium and memory loss that persist after recovery. Plus, the longer someone is immobilized, the more that muscles waste away, vessels clot and eventually organs malfunction. With COVID-19 patients lingering on ventilators, lasting side effects are a concern.

“The physical and mental toll is not small,” says pulmonologist Scott Aberegg, MD, who has treated patients with the disease in Utah and during the surge in New York City in April. There, he saw patients emerging from the ICU barely able to string a sentence together. “Only time will tell what the long-term effects will be.”

Researcher Frederik Denorme, PhD, investigates causes of complications that occur in the worst cases of COVID-19.

Researcher Frederik Denorme, PhD, investigates causes of complications that occur in the worst cases of COVID-19.

In patients with severe COVID-19, NETs become hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting that leads to organ failure.

In severe COVID-19, NETs become hyperactive and may trigger abnormal blood clotting, leading to organ failure and other complications.

NETs tell us about a potential mechanism for lung injury in COVID-19.

NETs tell us about a potential mechanism for lung injury in COVID-19.

Bhanu Kanth Manne, PhD, analyzes patient samples to understand mechanisms contributing to COVID-19 complications.

Bhanu Kanth Manne, PhD, analyzes patient samples to understand mechanisms contributing to COVID-19 complications.

In the Medical Intensive Care Unit, health care providers adapt to working under conditions that mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

In the Medical Intensive Care Unit, health care providers adapt to working under conditions that mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Physician-scientist Elizabeth Middleton, MD, treats COVID-19 patients in the MICU and carries out research with a goal of improving their outcomes.

Physician-scientist Elizabeth Middleton, MD, treats COVID-19 patients in the MICU and carries out research with a goal of improving their outcomes.

On March 17, after five days in intensive care, Chow regained enough strength to go home. It took three more weeks to wean off of supplemental oxygen.

He told his followers on Twitter that of everything he went through, the isolation had been the worst. With medical staff at the ICU draped head-to-toe in face shields and gowns, he couldn’t tell what they looked like, much less glean comfort from a reassuring smile. Kept in a solitary room to prevent his infection from spreading, Chow was left to endure the hardest days with little human contact.

Even at home, he was sent to recover in quarantine. His wife dropped off meals outside his door “as if I were a prisoner” while he remained alone in the basement.

“Not being able to see your family, not being able to get comfort. The fear of dying alone,” Chow told his social media followers. “…The feeling is real and even worse than the physical problems.”

Uncharted Territory

14 weeks after leaving the hospital, Chow’s body still bears remnants of his worst days. Long conversations turn into coughing fits and ascending the stairs can feel like climbing Mount Everest. “I feel like I’m at 85%,” he says.

With 7% of Utahns and 2.5% of Americans in his age group needing hospitalization for COVID-19, he knows his case is not typical. But he also knows how bad it can be. Researchers are working hard to develop vaccines, treatments and technologies that will bring us to the other side. Until we get there, Chow is doing his part to prevent the worst from happening to someone else.

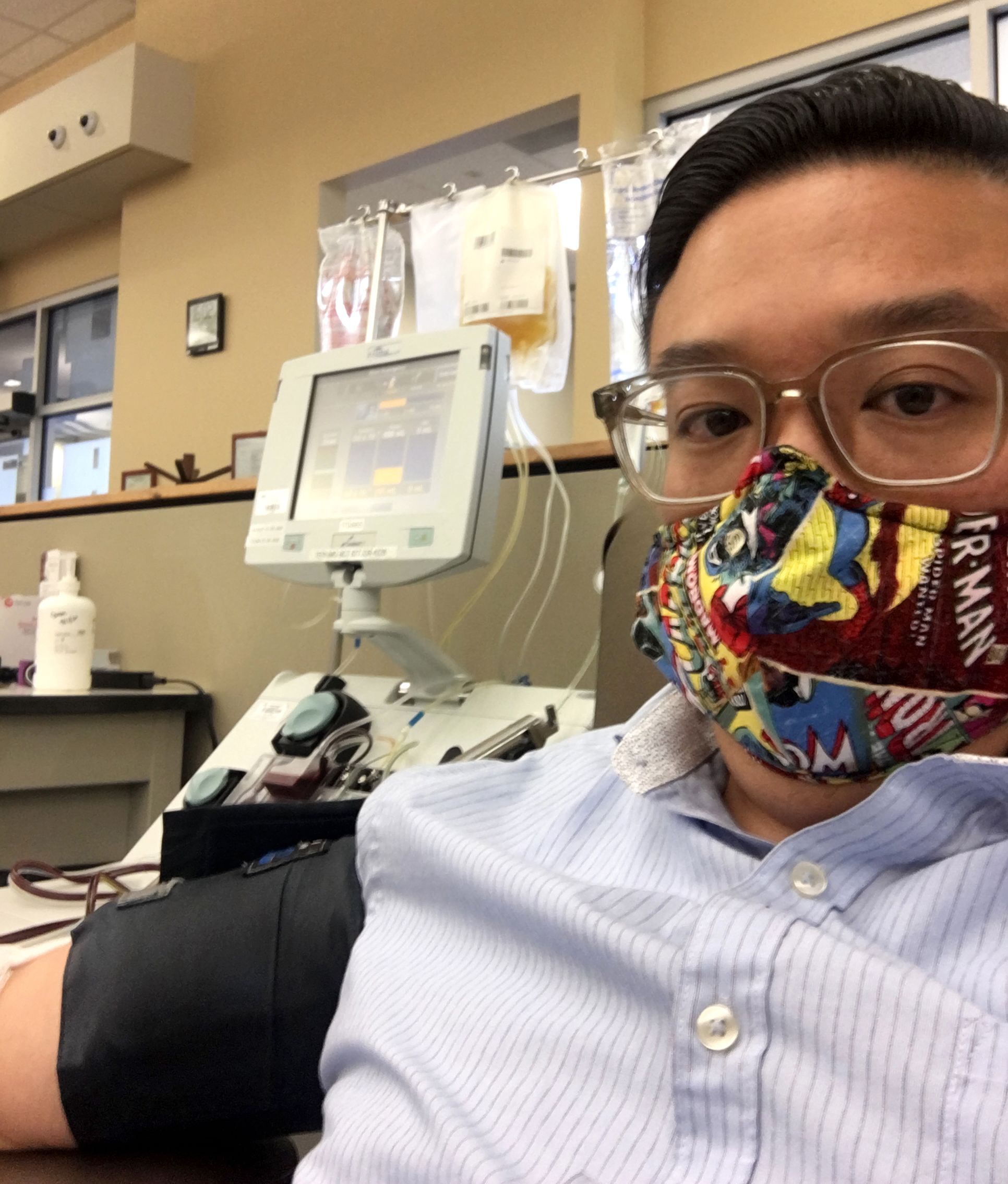

Chow donates plasma—which wields antibodies against the coronavirus—as often as he can.

Chow donates plasma—which wields antibodies against the coronavirus—as often as he can.

His research lab still mostly sits unoccupied. He encourages his trainees and staff to work from home as much as possible. He donates his plasma as often as he can in the hopes that the antibodies he wields will help someone else turn the corner. On social media, he leverages his scientific expertise to educate his vast audience about the virus, the disease, and the rationale for wearing a mask.

But mostly, he is devoting time to family.

Back on Twitter, he captures a scene with his kids. His son, Micah, and daughter, Emery, are playing doctor and he is the patient. Emery takes plasma from him with a leaf and gives him “plasma tea” to make him better.

“Daddy, you haven’t given enough,” Micah observes. “I need to take more.”

Chow gladly gives him all that he can.

Clement Chow with his wife, Candace, and children, Emery and Micah, at home.

Clement Chow with his wife, Candace, and children, Emery and Micah, at home.

Through patient care, research, and education, University of Utah is leading the way to help those impacted by COVID-19. Learn how.

Story by Julie Kiefer

Design: Jessica Cagle

Photography:

Clement Chow (Selfies-masked, MICU, donating plasma)

Robert Campbell (Fredrik Denorme, Bhanu Kanth Manne)

Christian Con Yost (NETs)

Nathan Hatton (MICU)

Lauren Moulton (Elizabeth Middleton)

Charlie Ehlert (Chow family)

Thank you to Nick McGregor, Nafisa Masud, and Doug Dollemore for helpful comments and suggestions.