PIONEERING

THE FUTURE

Stories of Discovery & Innovation

at University of Utah Health

Women's Health

August 17, 2021

Researchers at University of Utah Health are improving the quality of life for women by advancing health care options from contraception to cancer care. By focusing on technology, our scientists have customized systems to treat breast cancer non-invasively. A second approach highlights the power of informing decisions with meaningful data: With results from U of U Health studies, clinicians and policymakers are equipped to make better, evidence-based decisions as they care for patients and work toward more equitable health care access.

Most women with breast cancer will undergo surgery to remove their tumor. That means some pain and scarring from the procedure are inevitable, even if the cancer is small. There is room for improvement, and U of U Health scientists have women’s interests in mind as they innovate new solutions.

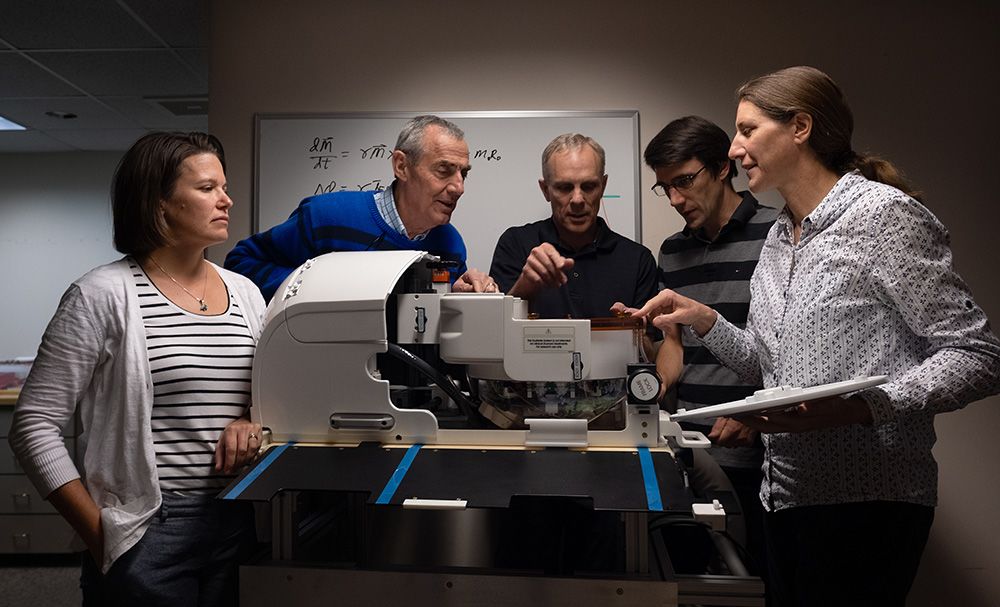

A team led by Allison Payne, PhD, a mechanical engineer in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, developed a system that destroys small tumors non-invasively, using high-intensity ultrasound waves. The system, called Muse, is specifically designed to treat small tumors in the breast. During treatment, a patient lies on a customized table with her breast suspended in a cylinder. An MRI coil in the cylinder generates a detailed image of the breast. Then, a physician uses that image to direct the ultrasound, targeting the tumor while sparing healthy tissue. Muse is now being evaluated in clinical trials, bringing breast cancer treatment a step closer toward fewer side effects and better cosmetic outcomes for women.

Learn more about this discovery.

When a pregnancy reaches 39 weeks, it is considered “full term.” The risk of complications increases if pregnancy continues, but until recently, if both mother and baby were healthy, doctors usually waited until 41 weeks to induce labor. That’s because there was a concern that inducing delivery at 39 weeks would make a cesarean delivery more likely. Being a major surgery, cesareans increase the risk of complications to mother and baby.

Clinical research at U of U Health, however, relieved these concerns and showed that induction at 39 weeks is reasonable for first-time mothers. In a clinical trial involving more than 6,000 women with low-risk pregnancies, Robert Silver, MD, and colleagues in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology found that women whose labor was induced at 39 weeks had fewer cesarean deliveries than women who waited for spontaneous labor. Contrary to what had been though before, this seminal study found that electing to induce labor may give the best chance for vaginal delivery and improves medical outcomes for mother and baby.

Some methods of contraception are more difficult to use than others, and all reversible methods fail occasionally, even with perfect use. A variety of factors influence women’s choices about contraception. But U of U Health scientists have shown that when cost is eliminated, demand for the most effective forms of birth control goes up.

Led by David Turok, MD, associate professor in the Division of Family Planning partnered with Planned Parenthood of Utah to study the impact of making all forms of contraception available free of charge to thousands of women. They found that when cost was not a consideration, women were more likely to choose more effective methods, including intrauterine and other implantable devices. Demand for those methods increased even further when women were offered online education about family planning options. The study’s findings led to the foundation of Family Planning Elevated, a U of Uw Health initiative that is helping community health organizations provide no-cost contraception to uninsured, underinsured, and undocumented Utahns statewide.

The flu can be a serious illness, and infants and pregnant women are among those most vulnerable. Flu shots are safe and recommended for pregnant women, but babies cannot be vaccinated against the flu until they are six months old. Infants must depend on others to protect them from the virus.

U of U Health scientists have found one more reason pregnant mothers should get the flu shot. It protects the baby, too. Pediatrics associate professor Julie Shakib, DO, and colleagues analyzed health records from more than 249,000 infants and found that mothers who received flu vaccines during pregnancy were much less likely to develop the illness themselves. Over the course of nine influenza seasons, 97 percent of laboratory-confirmed flu cases in the study group occurred in infants whose mothers were not immunized against the virus while pregnant. What’s more, vaccinating expectant mothers reduced infants’ risk of influenza-caused hospitalization by more than 80 percent. “Vaccines are a gift that the mother can give to her baby before the baby is even born," Shakib said.

Pioneering the Future: Stories of Discovery & Innovation at University of Utah Health

Special thanks to Wes Sundquist and Alfred Cheung for their dedicated work compiling research discoveries.

Written by: Jennifer Michalowski

Editing by: Julie Kiefer

Layout and Design by: Kyle Wheeler

Production Supervision: Abby Rooney, Julie Kiefer, Kyle Wheeler

Supported by: Will Dere, Chris Hill, Amy Tanner