University of Utah Health to Construct Education Building for the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

The new center will be home to cutting-edge medical education, simulation, and research facilities

The moment she saw the patient, Jane knew that she had little time. Medical technicians had just rolled in a 36-year-old male with third-degree burns. Peeling black-and-white wounds snaked around his shoulder and down his chest. In spots, she wasn’t sure where his clothing stopped and his skin began.

The patient, she was told, was working on a home-improvement project when sparks flew from a tool and set fire to a wall near a propane tank. He was trapped inside for nearly two minutes before making it out.

Jane quickly began running through a mental checklist of how to assess her patient and what instructions to give her fellow teammates when the patient began to scream. The man’s father rushed past the front desk, crying, begging to see his son. As Jane watched other attendants pull the father back, the patient suddenly went into cardiac arrest.

Things were unfolding so quickly, Jane suddenly couldn’t think. She needed advice.

So, she paused for a reality check—a literal one.

Everyone in the emergency room froze as Jane removed her virtual-reality headset and turned to her instructor for guidance. Jane was taking part in a University of Utah School of Medicine training simulation. The burn patient, grieving father, and busy emergency room were all virtual, part of a new interactive software program designed to replicate medical scenarios.

Welcome to the future of medical education.

“It’s one thing to teach medicine within a classroom, but often we don’t control the environment. How do you juggle information coming in—what you see and hear—and manage your surroundings while in a heightened state? The situation affects our choices. Using tools such as virtual reality, we can now more accurately simulate such moments.”Sara M. Lamb, MD., Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine Associate Dean for Curriculum

The facility for this new vision of medical training isn’t a reality yet for School of Medicine students, but in a few years it will be.

University of Utah Health is embarking on the construction of a new state-of-the-art facility embedded in its health-sciences campus. The new School of Medicine building will ensure the School of Medicine has an advanced home that enables cutting-edge training, such as Jane’s simulation, and can anticipate, adapt, and integrate the rapid educational changes and demands that will arise over the next half-century.

“Since its founding in 1905, the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine at University of Utah has been a pioneer in medical education, research, and care. It is now our generation’s turn to carry that torch,” said Michael L. Good, MD, CEO of University of Utah Health, Senior Vice President for Health Sciences, and Dean of the School of Medicine. “The new School of Medicine building is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to cement our legacy as the region’s—and one of the nation’s—top medical schools by constructing a facility that accelerates the exceptional education and research that has long been a hallmark of the School of Medicine and our health-sciences enterprise.”

The new building was originally approved by the state legislature in 2017 with a $50 million commitment, followed by millions more in philanthropic pledges. On June 9, 2021, a major contribution to the new building was announced from the George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation and the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation.

THE POWER OF SIMULATION

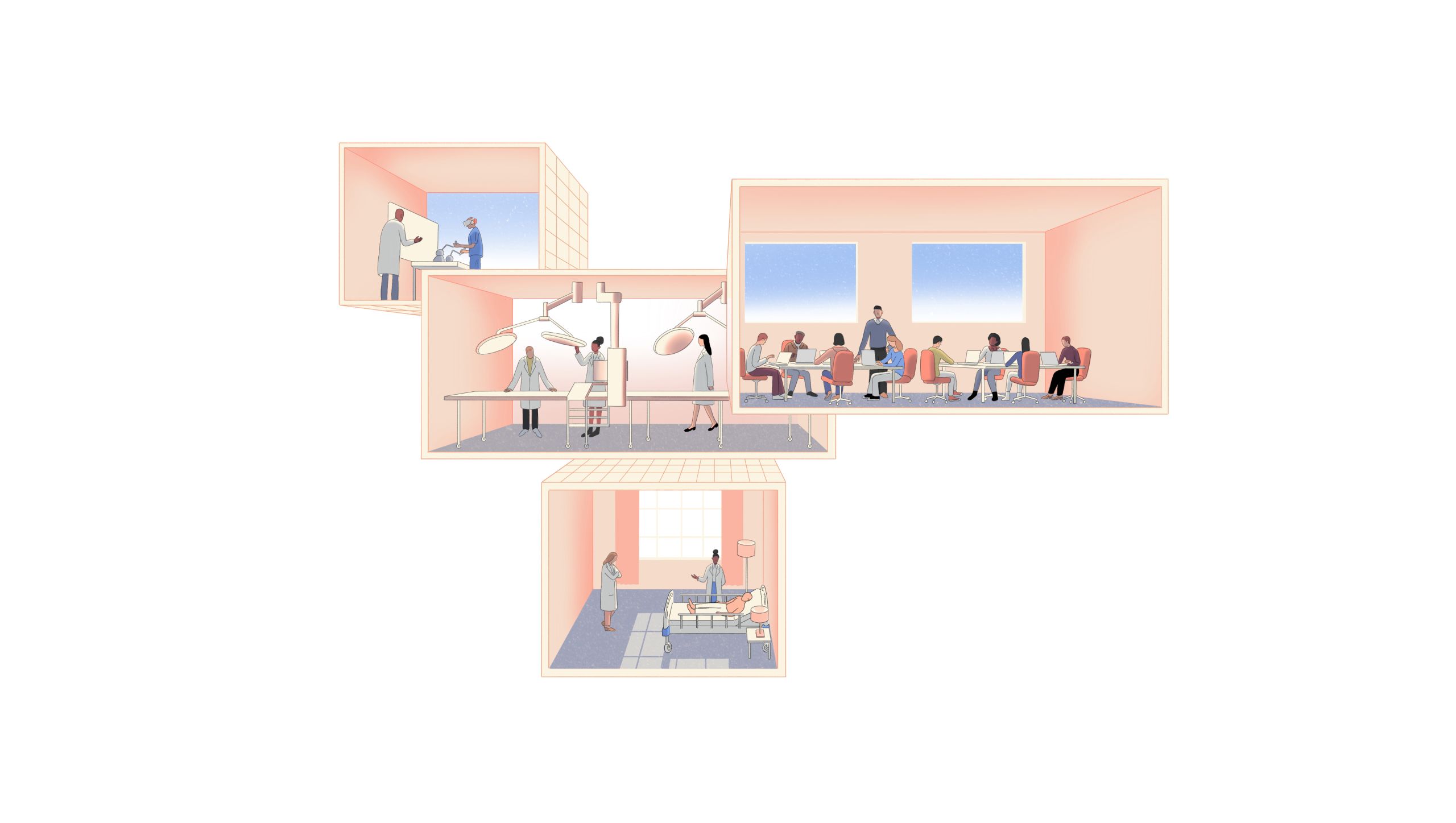

The heart of the new facility will be advanced and flexible education facilities, including virtual- and physical-simulation spaces.

“This new facility will allow us to build around the latest techniques in education from the ground up,” said Dr. Lamb. “We’re moving away from traditional, auditorium-style lectures—the ‘sage on a stage’ approach that is just a transfer of knowledge—to interactive experiences, small group discussions, and simulation.”

U of U Health students across the health sciences already use simulation, such as in the College of Nursing Simulation Center, where mannequins equipped with sophisticated technology replicate real patients from infancy to the elderly.

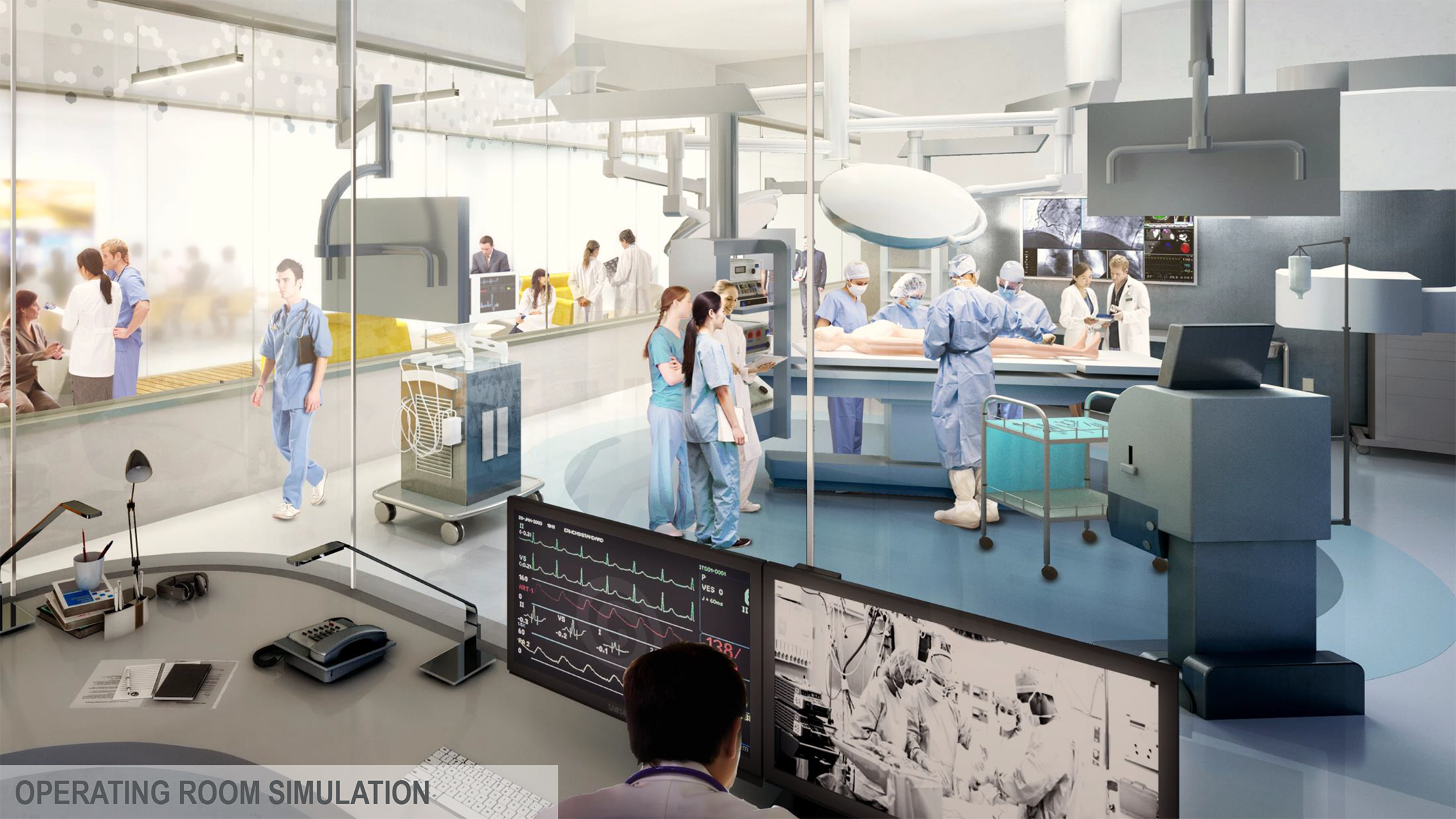

The new School of Medicine building will expand upon those capabilities with the Dumke Center for Advanced Medical Simulation, which will feature multiple simulation spaces, physical and virtual, each with a different focus. Instructors will be able to build and design environments for teaching and observation that simply do not exist today.

In addition to the type of virtual reality simulation students like Jane will experience, there will also be larger physical theaters designed to replicate clinical environments, treatment areas, patient rooms, outdoor settings such as the desert or mountains, and mock operating rooms.

Combined with the College of Nursing’s center and other areas across campus, U of U Health will boast the most-advanced medical-simulation training program in the Mountain West.

“Simulation has evolved so much in 20 years,” Lamb said. “We can do pretty remarkable things, but we’ve been limited by access to space and finances. Within the new building, we will be able to create nearly authentic experiential opportunities for the students. And as the technology improves and becomes more affordable, our capabilities will grow.”

DISCOVERY CENTER

Within the Discovery Center, researchers and students will develop, display, and implement innovations in teaching, research, and clinical outcomes. “Students will not just learn about new discoveries or train on new medical technology—they’re going to create them,” said Bernhard Fassl, MD, the interim co-director of the Center for Medical Innovation. “We will bring together faculty, researchers, and students from across disciplines to address some of the most pressing issues in medicine today.”

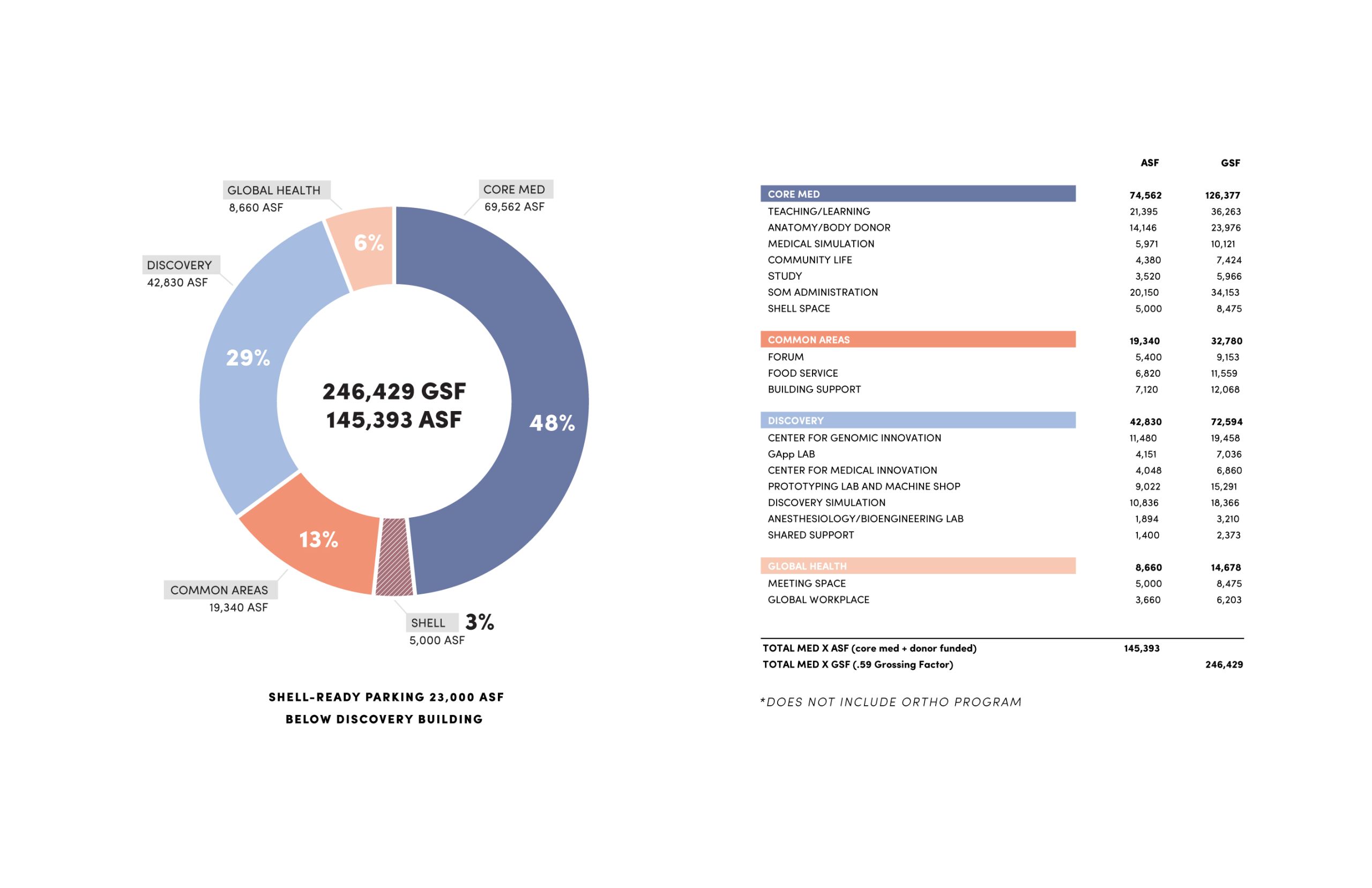

Made possible by a substantial donation and accounting for nearly a third of the overall footprint, the new center will house leading-edge simulation and 3D printers to create both products and techniques to be used for teaching future clinicians, researchers, and educators.

The Discovery Center includes:

The Center for Genomic Innovation, which researches and identifies genes that play a role in disease.

The Therapeutic Games and Apps (GApp) Lab, which develops interactive, medically focused games and applications.

The Center for Medical Innovation, which helps new ideas and products come to life by connecting innovators throughout the university and guiding them through the many stages of development. The center serves as a hub between health sciences, engineering, business, computer science, and entertainment and arts.

A Prototyping Lab and Machine Shop, which repairs existing devices, and designs and fabricates new products for the School of Medicine.

The Anesthesiology Bio Engineering Laboratory, which develops and tests medical devices for use during anesthesia and intensive care. The laboratory will focus on translational applications—creating technologies that find their way to bedsides and marketplaces.

“Currently, all of these related groups are scattered throughout the health-sciences campus,” said Steve Panish, the U’s Assistant Vice President for Capital Programs & Space Health Sciences. “For the first time, we will be able to bring them all together under one roof to amplify their strengths.”

The impact will also extend to students beyond the School of Medicine—and beyond U of U Health.

“The Center for Medical Innovation attracts a number of students from engineering, biochemistry, and other areas. We also have a very close working relationship with the Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute,” Fassl said. “We receive requests from industry asking us for a workforce with a broader set of experiences. With the new building comes a new prototyping lab and an enormous expansion of our computer science facility. So the number of projects and the number of students that we can take on will be significant.”

GLOBAL HEALTH

The new School of Medicine building will advance the U’s commitment to improving health-care systems and outcomes around the world.

Plans call for space in the building dedicated to Global Health. These work and meeting spaces will provide a central hub that makes collaboration easier for many global-health groups scattered through the health-sciences and main campus.

These groups are saving lives by improving the quality of health care in less-developed areas. Health problems that are easily treated in wealthier countries can devastate families, costing lives in many low- and middle-income communities.

“Our mandate is to cover the global space,” said Juan Carlos Negrette, director of Global Health. “Being global is different than being just international. International is only looking abroad; we have an introspection. We look in our common spaces here. We work with our Indian nation, and at the same time, we work in the international space and we expect to connect these dots. We see that there are common needs across the globe.”

Many of the global-health groups will continue to exist in their current homes, but the building will offer a space to work together, teach, and innovate. There will be several benefits that result from this. Among them:

- It will enhance learning opportunities for U of U health-science students—in particular, those enrolled in the School of Medicine, College of Nursing, and College of Pharmacy.

- Its tele-educational features will improve international teaching of students and providers in foreign countries.

- It will strengthen the university’s ability to solicit and win contracts with foreign governments, a valuable source of revenue and prestige for the U.

- It will provide a more-impressive space for foreign visitors. The U has a footprint in more than 60 countries currently.

“We are present all over the planet. We could put a lot of pins on a map,” Negrette said. “The new facility will project the global-health spirit of the university, which is ambitious.”

CORE MED

Ask any physicians, and they can likely tell you about their first experience in the anatomy lab. School of Medicine students spend a significant portion of their education learning the anatomy of the human body by dissecting a cadaver.

“It’s a rite of passage going back hundreds of years,” said David Morton, assistant professor of neurobiology, who oversees the anatomy lab. “Knowing that the cadaver on the table was once a living person brings a profound humanity to the learning experience. That experience cannot be simulated.”

Unfortunately, the U’s anatomy lab long ago became outdated. For more than two decades, it has been located in Research Park, more than a mile away from the School of Medicine.

The anatomy lab falls short of modern standards—in particular with its lighting and ventilation.

“You’re spending hours a day in a basement without windows,” fourth-year medical student Addie Langner said. “It would definitely be more pleasant to have some natural light.”

Since medical students are required to spend significant time in the lab, they must arrange to leave the main school building and drive to the lab, where there is limited parking. Both Langner, who is co-president of the School of Medicine student body, and Morton say that students waste time commuting and find it especially tedious during the dark winter months.

In order to minimize the trips, they often consolidate their schedules.

“This means students spend less time here,” Morton said. “Students need more opportunities to gain experience in anatomy, not less.”

The new School of Medicine building brings the anatomy lab into the same facility as the medical school, saving students countless hours of transportation time each year.

“Now medical students will be able to move seamlessly from class to the lab, from the theoretical to the practical, within minutes,” Morton said.

Located on the top floor with modern high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) ventilation, the lab will include natural lighting. This feature, which Morton said few anatomy labs have, will make it a much more pleasant place to learn than a dark basement.

The new anatomy lab will be close to other related medical facilities, such as new simulation and ultrasound spaces. And like so many other components of the building, the anatomy lab will allow for opportunities to develop partnerships that advance education—partnerships that are almost impossible to form today. Morton foresees possibilities to work with areas such as the Dumke Center for Medical Simulation on high-tech mannequins.

“The more I learn about the different facets of the new building, the more I get excited about what we could do in the future,” Morton said.

Throughout the Core Med area, classrooms will range from small in scale to grand auditoriums. Large sections of students can assemble for a class, easily break into small groups, and then quickly reassemble.

“What we are really looking for are flat classrooms with students facing one another in acoustically reasonable spaces, so that students can learn through conversation and curiosity-based learning,” Lamb said.

Small, private groups are where a lot of the work happens in medical school, and in the new building, there will be no shortage of available workspaces that are conducive to hours upon hours of studying and team projects.

The Core Med area will also be the home of School of Medicine administration, including the dean and senior leaders, admissions, registration, student support, and the Alumni Association. These nearby offices will offer students easy access to the people and opportunities that can expand their learning—and it will build a stronger educational community.

“The new School of Medicine building will provide an opportunity for our faculty to comingle with students to a much greater degree than what we do now,” Lamb said. “That kind of collaboration will be essential.”

PROMOTING WELLNESS AND SUCCESS

Medical professionals at all levels increasingly struggle with the emotional and physical exhaustion brought on by high stress, also known as burnout.

It’s an issue that often starts in medical schools. Roughly half of all medical students suffer from feelings of anxiety or depression that can lead to burnout at some point during their education.

The reasons for this are complex, explains Michelle Vo, director of student wellness at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine. They include the difficulty of the curriculum and long hours of study associated with it, and the fact that so many medical students have relentlessly pursued academic excellence throughout their lives, without a break.

“There’s a stigma associated with vulnerability,” Vo said. “People who go into medicine think they shouldn’t struggle, and they personalize it. They’re very high-performing, high-achieving, driven people who are accustomed to pushing through any sort of distress, and that often works for them until they hit a wall.”

Well-being and the idea of resilience—the ability to recover from setbacks or difficult situations—have emerged as a priority for faculty, researchers, residents, and students in the academic-medicine community.

U of U Health is committed to creating environments where faculty, staff, residents, and students thrive, and to ensuring that doctors have coping and wellness strategies that they will need as they grow personally and professionally. Vo’s office has significantly expanded during her five years at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine, increasing from a staff of two to 12. She said their work will be enhanced by the Huntsman Mental Health Institute, which will include student wellness as one of its focuses.

The new building will incorporate facilities and resources that expand innovative programming while also housing resources essential to professional fulfillment. The aim will be to create an optimal work environment, while promoting personal resilience and reducing individual burdens.

For example, one difficulty students with families face is their struggle with extended absences from loved ones. As a result, the building will have a family-room space to allow visitation and connection. In addition, there will be dedicated offices and space for personal consultations with licensed professionals, as well as peer, group, and crisis support.

The new building will also allow there to be increased focus on the wellness of all students, in particular those from underrepresented groups, such as students of color.

This summer, Dr. Good announced that the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine would create a $1 million scholarship fund, and asked for a challenge match from supporters, to be used for four-year, full-tuition scholarships for students underrepresented in medicine.

“In order to be good stewards of our community, we have to be as inclusive as possible,” Vo said. “We’ve been talking about well-being and community building [at U of U] for a very long time. We’re creating a space where everybody feels included.”

COLLABORATION SPACES

Of all the improvements, Lamb said that one of the things she looks most forward to are the unanticipated ones. “It’s the chance encounters. Some of the best ideas come when we get up and take a walk. When students, faculty, researchers, staff are able to spot each other in passing and share with one another—that’s where some real magic happens,” she said.

With those unexpected encounters in mind, one-seventh of the new building is designated as common areas, which can be thought of more as “collision spaces,” designed to facilitate interactions among students who don’t often come into contact.

“Right now we can be very isolated, kind of in our own little world,” Langner said. “The new School of Medicine building will encourage a lot more community among all of the health-science professions. That’s very exciting.”

Designed to make the building an accessible resource for both regular and occasional visitors, common areas include the forum, food service, and behind-the-scenes components such as information technology.

“There are a number of studies and cases—many even here at the U—citing how chance encounters lead to big ideas. In fact, the point of an academic campus is to create and foster an intellectual community,” said Kai Kuck, director of bioengineering at the U’s Department of Anesthesiology, whose laboratory is slated to be in the new building. “We have so many innovation powers that will all come together in that building. I think that’s going to be tremendous.”

THE TIME IS NOW

Two-thirds of all practicing physicians in Utah hail from the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine, and its stellar reputation extends far beyond the state: applicants to the school have tripled in the past three years. They are drawn to U of U Health, in part, because it affords them the opportunity to train at an academic medical center that has earned a top-10 national ranking for 11 years in a row in quality (Vizient, Inc., Quality & Accountability Study Rankings). The only other center in the country that can claim a streak this long is Mayo Clinic.

When the current School of Medicine facility was constructed in 1965, it was as an extension of the hospital and intertwined with live clinical facilities. As needs arose, new classrooms and collaborative buildings were added across campus, wherever there was available space. The anatomy lab, which is central to medical education, was added to a facility more than a mile from the school.

The facility has long been outdated, and the costs to bring it up to modern standards are prohibitive. A recent study, presented to the state legislature, found that the building was seismically unsound.

“So much about education has changed. The current building is just woefully out-of-date."

Addie Langner, Fourth-year Medical Student

Langner and other students provided input to guide the new design, along with faculty members, administration, and other key education and research stakeholders. “The new School of Medicine building creates a stronger, much more sophisticated environment for education,” she said. “I think this will take us to a new level.”

CEMENTING OUR LEGACY

The new School of Medicine building is the latest step in U of U Health’s multiyear campus transformation.

University Hospital Area E, the Craig H. Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital, and the Sugar House Health Center have already been built and are serving thousands of patients daily. Roadwork is currently taking place, and construction on the new School of Medicine building will begin in the near future.

When the building opens, the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine will be housed in a facility that offers unsurpassed learning opportunities—and is designed to stay that way, even as medical-education evolves in the decades to come.

Fundraising for the remaining budget of $75 million will continue through construction. Good said that he hopes all members of the U of U Health community will consider participating in the next chapter of the School of Medicine.

“We are at a moment in time when the need for public health could not be more evident,” Good said. “I am exceptionally proud of the work from our faculty, researchers, students, staff, benefactors, and all of the members of our community who offered tremendous input into the design of the new School of Medicine building. This will be a signature addition to our campus. More importantly, it will serve to dramatically enhance our medical-education experience. Generations of health-care providers, researchers, innovators, and medical professionals will pass through its halls, then move out to serve the people of our state, nation, and the world.”