FROM THE AMAZON TO THE REDWOOD HEALTH CENTER

Anna Gallegos' journey to advocating

for the health care needs of Utah's refugees

“I WANT TO SAVE THE WORLD.”

That was Anna Gallegos’ thought in summer 2014, when the then-22-year-old graduated from University of Utah Health’s four-year LEAP Academic Learning Communities program in health promotion and education.

“How am I going to do it?”

In the Amazon delta, on a humanitarian mission with 39 other LEAP graduates, she found the answer—at least at first. The group had flown to Iquitos, Peru, and taken canoes up the Amazon to Yanamono, buried in the Amazonian jungle in the north-eastern corner of Peru. Guides warned them not to dangle their fingers in the water for fear of disease and piranha, even though they saw people up to their waist fishing in its murky depths. “You feel very small,” she says. “The Amazon is so wide and long and brown.”

The first week, they built classrooms, sidewalks, and bridges while teaching English to locals. The second week, they ventured out to the Yanamono Medical Clinic run by Linnea J. Smith, MD, who in 1990 left her Wisconsin practice to provide medical services in Yanamono and train locals on basic first aid. She treated piranha bites that took out chunks of flesh, malaria, lacerations, and broken bones.

Gallegos (pictured left) admired the tired physician: “She knew that what she was doing needed to be done, and she was going to do it.” By the end of the week, Gallegos didn’t want to leave—she wanted to become a part of the efforts to provide health care to Yanamono’s impoverished population.

Back in Utah, she realized she didn’t have the courage to give up her family life and move to the wilds of Peru. If not South America, how might she make a difference in her hometown?

The answer, she discovered, was improving access to health care for refugees. The story of how Gallegos negotiated her way through labyrinths of language, culture, and health care systems to build a bridge for refugees begins in the Amazon but ends in the Salt Lake City homes of refugees who say Gallegos’ first name with almost breathless reverence.

Refugees like Asha. For her and her family, Utah is more than a new home; it’s a place of security and safety. Asha grew up in Somalia, only to see her mother-in-law and husband killed in front of her in 1992. She fled with her children to a refugee camp in Kenya, where she spent sleepless nights watching for snakes and mosquitos. “I was scared for my kids so I stayed up all night watching them,” she says through an interpreter. In August 2007, a resettlement agency brought the family to Utah, a place she describes as peaceful. After so long with little to no rest, “The moment I came here,” she says, “I fell asleep.

That was Anna Gallegos’ thought in summer 2014, when the then-22-year-old graduated from University of Utah Health’s four-year LEAP Academic Learning Communities program in health promotion and education.

“How am I going to do it?”

In the Amazon delta, on a humanitarian mission with 39 other LEAP graduates, she found the answer—at least at first. The group had flown to Iquitos, Peru, and taken canoes up the Amazon to Yanamono, buried in the Amazonian jungle in the north-eastern corner of Peru. Guides warned them not to dangle their fingers in the water for fear of disease and piranha, even though they saw people up to their waist fishing in its murky depths. “You feel very small,” she says. “The Amazon is so wide and long and brown.”

The first week, they built classrooms, sidewalks, and bridges while teaching English to locals. The second week, they ventured out to the Yanamono Medical Clinic run by Linnea J. Smith, MD, who in 1990 left her Wisconsin practice to provide medical services in Yanamono and train locals on basic first aid. She treated piranha bites that took out chunks of flesh, malaria, lacerations, and broken bones.

Gallegos (pictured above in Yanamono) admired the tired physician: “She knew that what she was doing needed to be done, and she was going to do it.” By the end of the week, Gallegos didn’t want to leave—she wanted to become a part of the efforts to provide health care to Yanamono’s impoverished population.

Back in Utah, she realized she didn’t have the courage to give up her family life and move to the wilds of Peru. If not South America, how might she make a difference in her hometown?

The answer, she discovered, was improving access to health care for refugees. The story of how Gallegos negotiated her way through labyrinths of language, culture, and health care systems to build a bridge for refugees begins in the Amazon but ends in the Salt Lake City homes of refugees who say Gallegos’ first name with almost breathless reverence.

Refugees like Asha. For her and her family, Utah is more than a new home; it’s a place of security and safety. Asha grew up in Somalia, only to see her mother-in-law and husband killed in front of her in 1992. She fled with her children to a refugee camp in Kenya, where she spent sleepless nights watching for snakes and mosquitos. “I was scared for my kids so I stayed up all night watching them,” she says through an interpreter. In August 2007, a resettlement agency brought the family to Utah, a place she describes as peaceful. After so long with little to no rest, “The moment I came here,” she says, “I fell asleep.

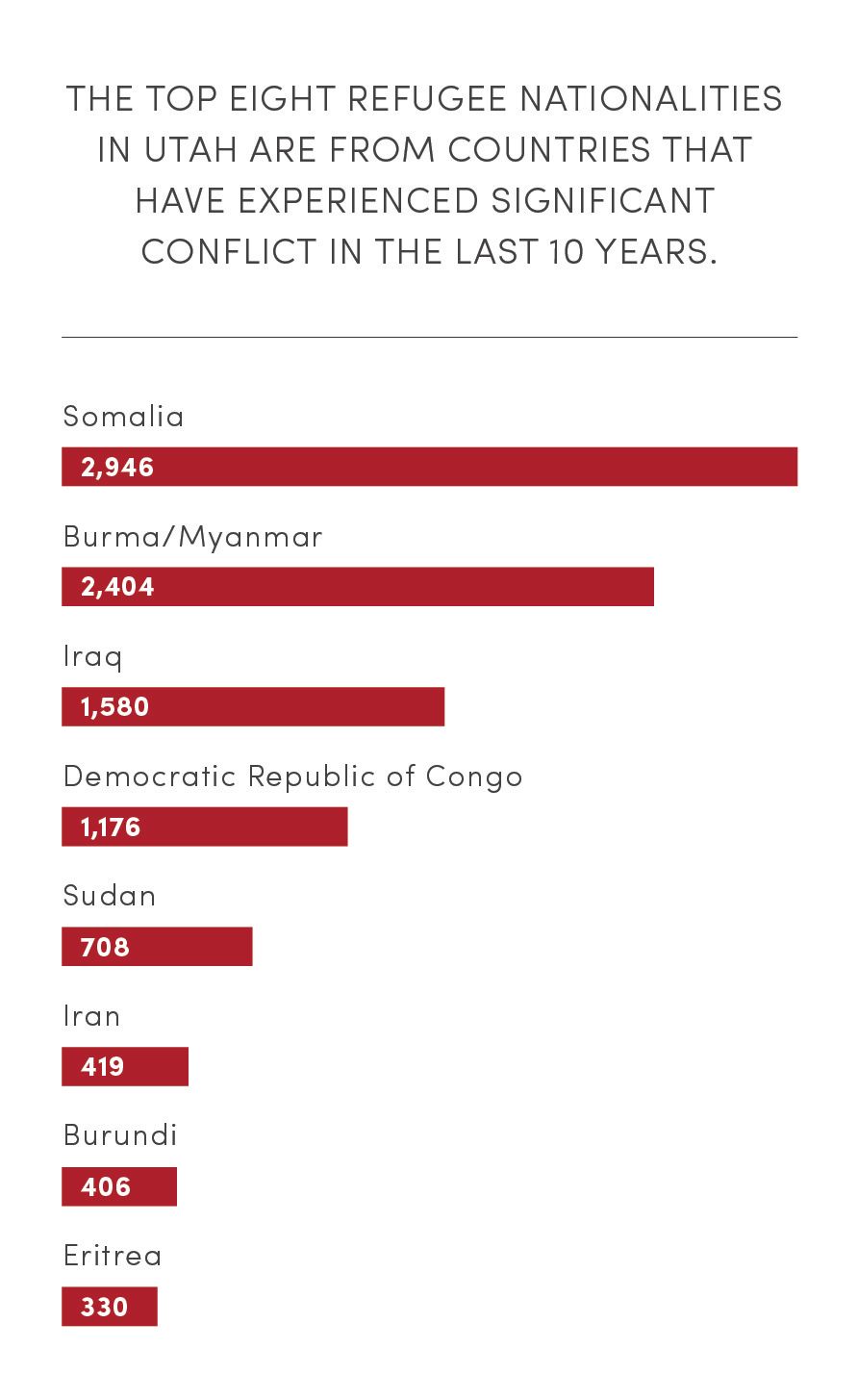

FLEEING PERSECUTION

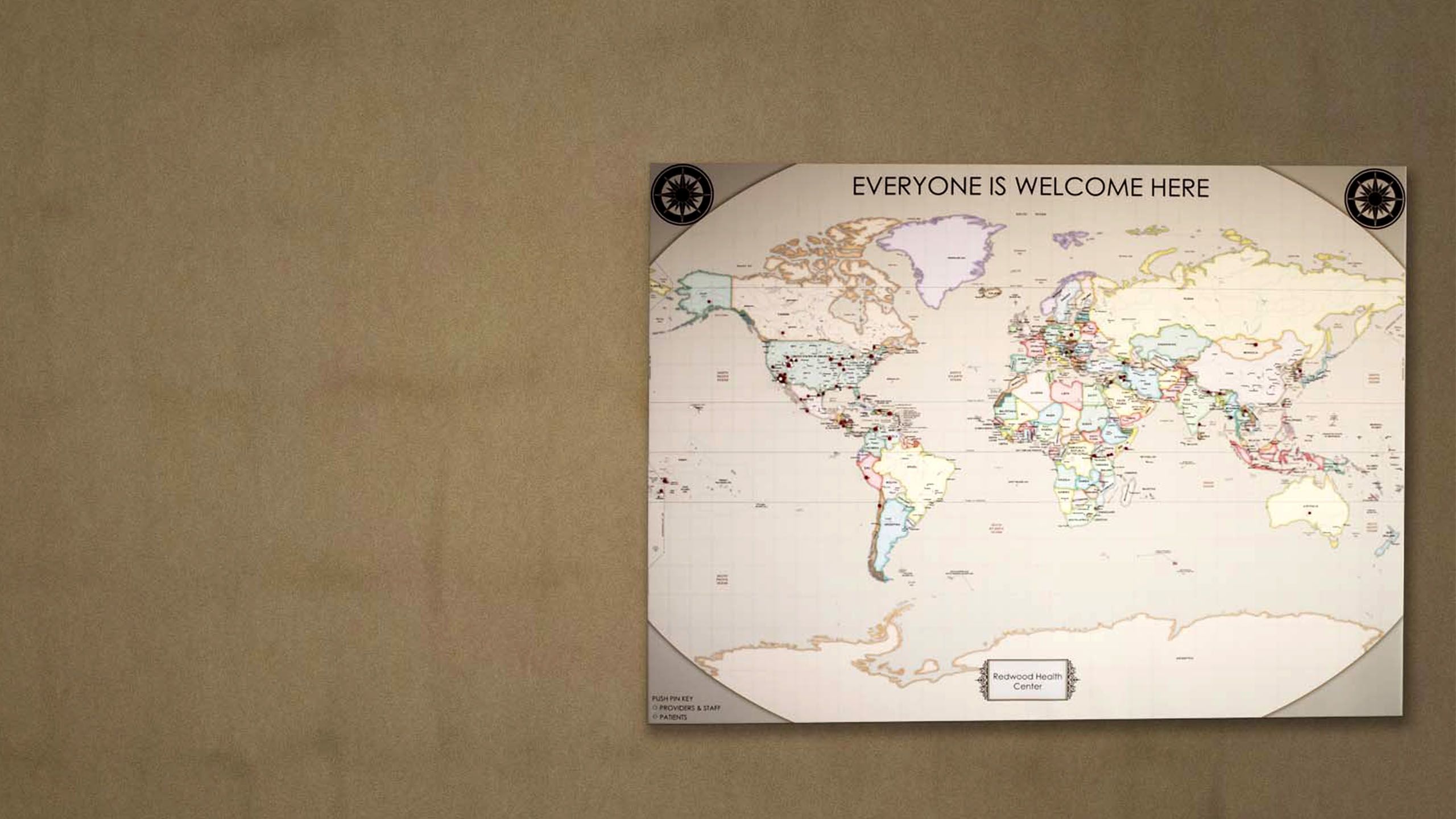

Redwood Health Center is on 2100 South, just a block or so east of Redwood Road. Approximately 50 percent of the center’s patients are refugees, due in part to it being close to an apartment complex that has long been home to refugees of diverse nationalities.

In October 2014, Gallegos started as a guest relations specialist at Redwood Health Center’s front desk. “Crazy stuff happens there,” she recalls. “Patients used us as an emergency department. They’d come in clutching a finger they’d cut off, or having just had a heart attack, or having a stroke in front of me.” She quickly got to know members of the rapid response team she summoned to the front desk on a first-name basis.

Despite the language barriers, refugees, some in brightly colored clothes, fascinated her. In those first months, she focused on learning patients’ names, building relationships, and trying to understand their concerns—language permitting—as she was checking them in.

“When somebody doesn’t understand the language, has to work two jobs to pay bills, has housing issues and school issues, it can take them a while to get some of those issues addressed,” says Aden Batar, director of immigration and refugee services for Catholic Community Services, one of two resettlement agencies in Utah. “Sometimes a medical appointment is not a priority for them when they have issues paying bills. It takes time. If we don’t coordinate those issues—if a client is late or misses an appointment and we’re not asking why—then we’re missing the point. Resettlement issues usually last a couple of years before a person stands on their feet.”

Redwood Health Center is on 2100 South, just a block or so east of Redwood Road. Approximately 50 percent of the center’s patients are refugees, due in part to it being close to an apartment complex that has long been home to refugees of diverse nationalities.

In October 2014, Gallegos started as a guest relations specialist at Redwood Health Center’s front desk. “Crazy stuff happens there,” she recalls. “Patients used us as an emergency department. They’d come in clutching a finger they’d cut off, or having just had a heart attack, or having a stroke in front of me.” She quickly got to know members of the rapid response team she summoned to the front desk on a first-name basis.

Despite the language barriers, refugees, some in brightly colored clothes, fascinated her. In those first months, she focused on learning patients’ names, building relationships, and trying to understand their concerns—language permitting—as she was checking them in.

“When somebody doesn’t understand the language, has to work two jobs to pay bills, has housing issues and school issues, it can take them a while to get some of those issues addressed,” says Aden Batar, director of immigration and refugee services for Catholic Community Services, one of two resettlement agencies in Utah. “Sometimes a medical appointment is not a priority for them when they have issues paying bills. It takes time. If we don’t coordinate those issues—if a client is late or misses an appointment and we’re not asking why—then we’re missing the point. Resettlement issues usually last a couple of years before a person stands on their feet.”

Through Gallegos’ daily interactions with clients like Asha, she learned about the persecution they fled in their homelands—often involving war, trauma, sexual violence, imprisonment, and torture.

“They gave me an opportunity to guide them through their health care navigation, even if I was doing it mostly from the front desk,” Gallegos says.

Gallegos became a de facto navigator, skilled at advocating for refugees with the clinic’s providers and insurers. Still, Gallegos struggled with cultural differences. When an Iraqi couple came in, they ordered her to make an appointment for them and waved their fingers in her face. “I had to take a step back from feeling frustrated and disrespected,” she says. “But looking back now, I didn’t understand the cultural background they were coming from.”

Through those informal efforts, Gallegos saw how much they struggled—even in the welcoming arms of refugee-friendly Utah. The more attention she paid to refugee patients, the more she encountered disconnects between them and providers. What emerged was a nuanced portrait of interactions that, while reflecting well on staff efforts, also raised concerns.

Through Gallegos’ daily interactions with clients like Asha, she learned about the persecution they fled in their homelands—often involving war, trauma, sexual violence, imprisonment, and torture.

“They gave me an opportunity to guide them through their health care navigation, even if I was doing it mostly from the front desk,” Gallegos says.

Gallegos became a de facto navigator, skilled at advocating for refugees with the clinic’s providers and insurers. Still, Gallegos struggled with cultural differences. When an Iraqi couple came in, they ordered her to make an appointment for them and waved their fingers in her face. “I had to take a step back from feeling frustrated and disrespected,” she says. “But looking back now, I didn’t understand the cultural background they were coming from.”

Through those informal efforts, Gallegos saw how much they struggled—even in the welcoming arms of refugee-friendly Utah. The more attention she paid to refugee patients, the more she encountered disconnects between them and providers. What emerged was a nuanced portrait of interactions that, while reflecting well on staff efforts, also raised concerns.

Source: Omaha World-Herald

Source: Omaha World-Herald

Source: Omaha World-Herald

Source: Omaha World-Herald

THE AMERICAN WAY

When these patients came to the clinic—sent there by refugee resettlement agencies or providers who didn’t work with refugees—many had no idea what they were there for or what they needed. Some didn’t have insurance but insisted on being seen. They’d want to see a doctor for a pregnancy test without realizing they could buy one at the pharmacy. Their agency case manager scheduled an appointment for them but they arrived hours late—or went to the wrong clinic.

They were instructed to check on their glucose level regularly and then didn’t follow up. Sometimes they were stranded at the clinic after their appointment, not knowing how to get home.

On occasion, friction surfaced between patients struggling to express themselves and staff frustrated at missed appointments or failures to return for check-ups. Staff would talk about patients in front of them or say, “In America, this is what we do,” all while chiding them for missed appointments.

“If providers can’t look at the whole picture, they’ll only see [that patients are] missing their glucose level updates,” Gallegos says. “What they won’t know is that’s because they are worried about getting evicted or their kids fighting at school. They can’t focus on health and maintenance if they can’t get their basic needs addressed."

Navigating such complex issues, however, meant the clinic’s primary care providers spent more time with their refugee patients than typical appointment allotments—even though they are held to the same compensation structure as elsewhere in U of U Health’s system. “It speaks to their dedication that they’re willing to hear those difficult stories and care for those complex patients, day-in, day-out,” says Kathryn Young, who until recently was the center’s patient experience manager and Gallegos' supervisor.

Young started at Redwood as a nurse before becoming a manager in 2014. “Redwood is this gem in Salt Lake,” she says. “I haven’t come across a place that has the diversity that Redwood brings.” As a nurse, the unimaginable horror of stories she heard from Somalian refugees left Young with an intense desire to do something more. “It’s lovely to touch people individually as a nurse, but I wanted to make a difference at a population level,” she says. This passion made her and Gallegos effective partners in tackling process and system barriers while tightening key partnerships with resettlement agencies that would ultimately result in Redwood becoming a cutting-edge provider in refugee health care.

When these patients came to the clinic—sent there by refugee resettlement agencies or providers who didn’t work with refugees—many had no idea what they were there for or what they needed. Some didn’t have insurance but insisted on being seen. They’d want to see a doctor for a pregnancy test without realizing they could buy one at the pharmacy. Their agency case manager scheduled an appointment for them but they arrived hours late—or went to the wrong clinic.

They were instructed to check on their glucose level regularly and then didn’t follow up. Sometimes they were stranded at the clinic after their appointment, not knowing how to get home.

On occasion, friction surfaced between patients struggling to express themselves and staff frustrated at missed appointments or failures to return for check-ups. Staff would talk about patients in front of them or say, “In America, this is what we do,” all while chiding them for missed appointments.

“If providers can’t look at the whole picture, they’ll only see [that patients are] missing their glucose level updates,” Gallegos says. “What they won’t know is that’s because they are worried about getting evicted or their kids fighting at school. They can’t focus on health and maintenance if they can’t get their basic needs addressed."

Navigating such complex issues, however, meant the clinic’s primary care providers spent more time with their refugee patients than typical appointment allotments—even though they are held to the same compensation structure as elsewhere in U of U Health’s system. “It speaks to their dedication that they’re willing to hear those difficult stories and care for those complex patients, day-in, day-out,” says Kathryn Young, who until recently was the center’s patient experience manager and Gallegos' supervisor.

Young started at Redwood as a nurse before becoming a manager in 2014. “Redwood is this gem in Salt Lake,” she says. “I haven’t come across a place that has the diversity that Redwood brings.” As a nurse, the unimaginable horror of stories she heard from Somalian refugees left Young with an intense desire to do something more. “It’s lovely to touch people individually as a nurse, but I wanted to make a difference at a population level,” she says. This passion made her and Gallegos effective partners in tackling process and system barriers while tightening key partnerships with resettlement agencies that would ultimately result in Redwood becoming a cutting-edge provider in refugee health care.

REMOVING BARRIERS, BUILDING BRIDGES

While working at the front desk, Gallegos set about developing a refugee welcome packet. “I wanted to learn more about them,” she says. As Gallegos worked on the packet, she realized that coordination with the resettlement agencies and better understanding of refugees’ social determinants of health were fundamental for the clinic to take a more comprehensive and impactful picture of refugees’ health.

The resettlement agencies told her they didn’t want a paper-printed welcome document for refugees. “Even if I got it translated, a lot of them aren’t literate in their own language,” was the typical response she heard from agency providers. Instead, what was needed was a full-time refugee coordinator who could dedicate their time to helping refugees navigate the health system while smoothing out the kinks in the system to provide care. It was a job Gallegos was ideally suited to and positioned for, so in early 2017 she started assembling it.

Almost a year later, Gallegos was named refugee coordinator, a position she and Young believe is unique in Utah.

“I thought it would be easy,” Gallegos says. “I told Kathyrn, ‘Give me three weeks. I’ll have this figured out.’” Young responded: “You’ll need more than that.

Young felt that part of Gallegos' new role would be “educating frontline employees and helping them understand the refugee experience so they can deliver the care they’re trained to.” Gallegos introduced cultural and refugee sensitivity training with staff departments. “There was some stigma regarding refugees and a big lack of understanding what a refugee is,” Gallegos says. It’s a term that’s easily thrown around and often confused with immigrant, she says—a mistake she recalls making herself in her first months at the front desk.

Gallegos’ position brought more structure to how the center works with the refugee population, Young says. What was missing was cultural bridging, which Gallegos defines as the integration of cultures through understanding. While providers were trying to bridge the cultural gap, only a third of the bridge, as she puts it, was there.

“Obviously we were doing something right,” Gallegos says. “It’s always been a safe and welcoming place for refugees and immigrants, even before my position. What was lacking was all the foundational knowledge of the dos and don’ts, the cultural resources that providers needed to better serve this population. Once that was in place, then the knowledge foundation bridge could be finished.”

While working at the front desk, Gallegos set about developing a refugee welcome packet. “I wanted to learn more about them,” she says. As Gallegos worked on the packet, she realized that coordination with the resettlement agencies and better understanding of refugees’ social determinants of health were fundamental for the clinic to take a more comprehensive and impactful picture of refugees’ health.

The resettlement agencies told her they didn’t want a paper-printed welcome document for refugees. “Even if I got it translated, a lot of them aren’t literate in their own language,” was the typical response she heard from agency providers. Instead, what was needed was a full-time refugee coordinator who could dedicate their time to helping refugees navigate the health system while smoothing out the kinks in the system to provide care. It was a job Gallegos was ideally suited to and positioned for, so in early 2017 she started assembling it.

Almost a year later, Gallegos was named refugee coordinator, a position she and Young believe is unique in Utah.

“I thought it would be easy,” Gallegos says. “I told Kathyrn, ‘Give me three weeks. I’ll have this figured out.’” Young responded: “You’ll need more than that.

Young felt that part of Gallegos' new role would be “educating frontline employees and helping them understand the refugee experience so they can deliver the care they’re trained to.” Gallegos introduced cultural and refugee sensitivity training with staff departments. “There was some stigma regarding refugees and a big lack of understanding what a refugee is,” Gallegos says. It’s a term that’s easily thrown around and often confused with immigrant, she says—a mistake she recalls making herself in her first months at the front desk.

Gallegos’ position brought more structure to how the center works with the refugee population, Young says. What was missing was cultural bridging, which Gallegos defines as the integration of cultures through understanding. While providers were trying to bridge the cultural gap, only a third of the bridge, as she puts it, was there.

“Obviously we were doing something right,” Gallegos says. “It’s always been a safe and welcoming place for refugees and immigrants, even before my position. What was lacking was all the foundational knowledge of the dos and don’ts, the cultural resources that providers needed to better serve this population. Once that was in place, then the knowledge foundation bridge could be finished.”

“TOP OF THEIR LICENSE”

In many ways, Utah is ahead of the game when it comes to caring for its 60,000 refugees. It’s one of the few states that provides support and services for two years; most states only offer six months. Catholic Community Services' Batar (left) says he’s a navigator—not a case manager. “You guide individuals,” he says.

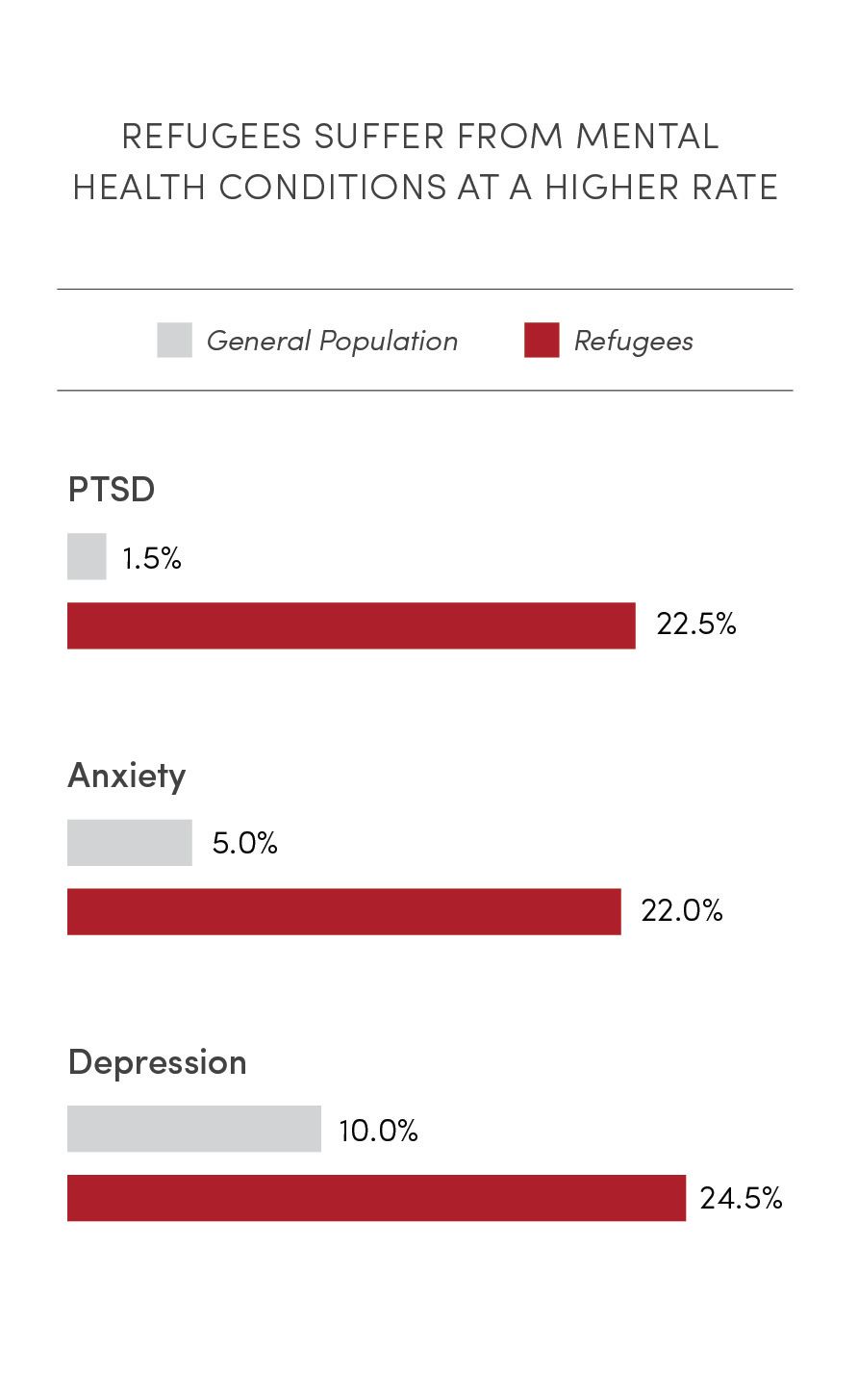

What providers don’t always understand, Gallegos and Batar say, is that refugees are often dealing with a raft of issues. They arrive in Utah as both individuals and families without resources. Most are burdened by health issues, PTSD and mental health concerns, war injuries, malnutrition, and women’s health issues.

“When somebody doesn’t understand the language, has to work two jobs to pay bills, has housing issues and school issues, it can take them a while to get some of those issues addressed,” Batar says. “Sometimes a medical appointment is not a priority for them when they have issues paying bills. It takes time. If we don’t coordinate those issues—if a client is late or misses an appointment and we’re not asking why—then we’re missing the point. Resettlement issues usually last a couple of years before a person stands on their feet.”

Aden Batar, director of migration and refugee services, at Catholic Community Services of Utah

Aden Batar, director of migration and refugee services, at Catholic Community Services of Utah

In many ways, Utah is ahead of the game when it comes to caring for its 60,000 refugees. It’s one of the few states that provides support and services for two years; most states only offer six months. Catholic Community Services' Batar says he’s a navigator—not a case manager. “You guide individuals,” he says.

What providers don’t always understand, Gallegos and Batar say, is that refugees are often dealing with a raft of issues. They arrive in Utah as both individuals and families without resources. Most are burdened by health issues, PTSD and mental health concerns, war injuries, malnutrition, and women’s health issues.

“When somebody doesn’t understand the language, has to work two jobs to pay bills, has housing issues and school issues, it can take them a while to get some of those issues addressed,” Batar says. “Sometimes a medical appointment is not a priority for them when they have issues paying bills. It takes time. If we don’t coordinate those issues—if a client is late or misses an appointment and we’re not asking why—then we’re missing the point. Resettlement issues usually last a couple of years before a person stands on their feet.”

Source: World Health Organization (WHO)

Source: World Health Organization (WHO)

Source: World Health Organization (WHO)

Source: World Health Organization (WHO)

Batar believes Redwood understands those issues—thanks in great part to Gallegos. “Right now, I can pick up the phone, call Redwood, and Anna will coordinate with their staff,” Batar says. “They’ll make sure they don’t miss appointments and their cultural needs are addressed.”

One person alone can’t manage all the work Gallegos’ position entails. “I’m trying, but it’s not efficient, because I can’t do everything,” she says. For now, she’s focused on staff and providers “working at the top of their license with these patients,” she says. “If I can help them build their cultural confidence, that takes a huge weight off me. It’s always a work in progress, but I think we’re pretty dang close.”

CCS’ Batar agrees that educating providers is fundamental. “If they don’t understand refugee issues, it makes it difficult for them to treat their patients,” he says. The providers need cultural background on the countries the refugees come from, ranging from the food they’re used to eating to the traditional medicine they use back home to addressing gender issues. “A Middle Eastern female doesn’t want to see a male doctor,” Batar explains.

Gallegos met with resettlement agencies and asked what their concerns were and learned there were challenges when working with the clinic. One was the agency and the clinic booking interpreters for the same client’s visit. “Our agency was obligated to pay that interpreter and the clinic would refuse to pay for them, so we were head-butting all the time,” Batar says. Then the clinic told them that their interpreters weren’t trained and hadn’t taken the required state certification. There were headaches, along with time and resources wasted, Batar says, which Gallegos patiently resolved. Next came finding a specialist. When a refugee client needed a specialist, they’d have to go to multiple people to get the appointment. Now agencies call Gallegos and she directs them to who their client needs to see.

Batar believes Redwood understands those issues—thanks in great part to Gallegos. “Right now, I can pick up the phone, call Redwood, and Anna will coordinate with their staff,” Batar says. “They’ll make sure they don’t miss appointments and their cultural needs are addressed.”

One person alone can’t manage all the work Gallegos’ position entails. “I’m trying, but it’s not efficient, because I can’t do everything,” she says. For now, she’s focused on staff and providers “working at the top of their license with these patients,” she says. “If I can help them build their cultural confidence, that takes a huge weight off me. It’s always a work in progress, but I think we’re pretty dang close.”

University of Utah Health CEO Michael Good, M.D., talking with patients at Redwood Health Center.

University of Utah Health CEO Michael Good, M.D., talking with patients at Redwood Health Center.

CCS’ Batar agrees that educating providers is fundamental. “If they don’t understand refugee issues, it makes it difficult for them to treat their patients,” he says. The providers need cultural background on the countries the refugees come from, ranging from the food they’re used to eating to the traditional medicine they use back home to addressing gender issues. “A Middle Eastern female doesn’t want to see a male doctor,” Batar explains.

Gallegos met with resettlement agencies and asked what their concerns were and learned there were challenges when working with the clinic. One was the agency and the clinic booking interpreters for the same client’s visit. “Our agency was obligated to pay that interpreter and the clinic would refuse to pay for them, so we were head-butting all the time,” Batar says. Then the clinic told them that their interpreters weren’t trained and hadn’t taken the required state certification. There were headaches, along with time and resources wasted, Batar says, which Gallegos patiently resolved. Next came finding a specialist. When a refugee client needed a specialist, they’d have to go to multiple people to get the appointment. Now agencies call Gallegos and she directs them to who their client needs to see.

HOW CAN WE HELP?

As soon as Gallegos and Young figured out one problem for a refugee family, more lingered in the shadows: housing, unemployment, nutritional issues, children struggling at school, and sometimes domestic violence.

While Gallegos doesn’t have any statistics to indicate the prevalence of domestic violence in Utah’s refugee communities, it’s an issue that Gallegos would like discussed in health promotion classes. “There are practices that maybe are OK back home but not here,” she says. When a patient comes in with domestic violence issues and their significant other is in the room, she says, the partner is only one of the barriers the clinic faces. There’s also culture and language issues, not to mention where could the woman and her children go to escape the perpetrator?

Gallegos is invested in every small success she witnesses at the clinic. “I know it really seems simple, but I’m proud of them for coming to their appointment on time,” she says.

Young found it “inspiring” to work with Gallegos before she left for a new job at the Sugar House Health Center. Gallegos is both a great “connector” and “an intense driver for good care, relentless in pursuing projects that make an impact with these patients,” Young says. “The biggest challenge has been figuring out how she can help—and figuring out what the need is. She’s broken down barriers I didn’t even think to break down.”

Gallegos worries about patients falling through the cracks and possible declines in the levels of provider and staff resiliency, all while she’s strengthening refugee health care. “It’s why I get so stressed out,” she says. “Sometimes it feels like a race.”

Batar would like to see more refugee coordinators in other locations like University of Utah Hospital, Moran Eye Center, Greenwood, Westridge and Sugar House Health Centers. “If each entity has their own coordinator to serve this population, I think that’s a win-win for everyone,” he says.

In the almost six years since Gallegos went to the Amazon rainforest, she’s come to appreciate a little of the burden the isolated provider, Linnea Smith, faced there. “I used to break down once a month,” Gallegos says. “Now I’ve learned to separate my feelings from someone else’s.” Laughing, she adds, “Now it takes six months for me to break.”

Gallegos describes the tattoo of a fir tree on her forearm as “my happy tattoo.” She feels at peace in the mountains, surrounded by beautiful trees and rock faces. When she’s up in the canyons, hiking in the woods, she still marvels at how caring for refugees has become the focal point of her professional life. “I didn’t know it would be refugees that would fill my heart and give me a purpose,” she says with a smile.

As soon as Gallegos and Young figured out one problem for a refugee family, more lingered in the shadows: housing, unemployment, nutritional issues, children struggling at school, and sometimes domestic violence.

While Gallegos doesn’t have any statistics to indicate the prevalence of domestic violence in Utah’s refugee communities, it’s an issue that Gallegos would like discussed in health promotion classes. “There are practices that maybe are OK back home but not here,” she says. When a patient comes in with domestic violence issues and their significant other is in the room, she says, the partner is only one of the barriers the clinic faces. There’s also culture and language issues, not to mention where could the woman and her children go to escape the perpetrator?

Gallegos is invested in every small success she witnesses at the clinic. “I know it really seems simple, but I’m proud of them for coming to their appointment on time,” she says.

Young found it “inspiring” to work with Gallegos before she left for a new job at the Sugar House Health Center. Gallegos is both a great “connector” and “an intense driver for good care, relentless in pursuing projects that make an impact with these patients,” Young says. “The biggest challenge has been figuring out how she can help—and figuring out what the need is. She’s broken down barriers I didn’t even think to break down.”

Gallegos worries about patients falling through the cracks and possible declines in the levels of provider and staff resiliency, all while she’s strengthening refugee health care. “It’s why I get so stressed out,” she says. “Sometimes it feels like a race.”

Batar would like to see more refugee coordinators in other locations like University of Utah Hospital, Moran Eye Center, Greenwood, Westridge and Sugar House Health Centers. “If each entity has their own coordinator to serve this population, I think that’s a win-win for everyone,” he says.

In the almost six years since Gallegos went to the Amazon rainforest, she’s come to appreciate a little of the burden the isolated provider, Linnea Smith, faced there. “I used to break down once a month,” Gallegos says. “Now I’ve learned to separate my feelings from someone else’s.” Laughing, she adds, “Now it takes six months for me to break.”

Gallegos describes the tattoo of a fir tree on her forearm as “my happy tattoo.” She feels at peace in the mountains, surrounded by beautiful trees and rock faces. When she’s up in the canyons, hiking in the woods, she still marvels at how caring for refugees has become the focal point of her professional life. “I didn’t know it would be refugees that would fill my heart and give me a purpose,” she says with a smile.

"From the Amazon to the Redwood Health Center"

Story by Stephen Dark

January 4, 2021

Design: Laurie Robison

Photographer: Jen Pilgreen and University Marketing & Communications

(Yanamono art courtesy of Anna Gallegos)

Stock Photography: Getty Images

Thank you to Anna Gallegos, Redwood Health Center, Nafisa Masud, Amy Albo, Kathy Wilets, and Nick McGregor