FINISHING THE RACE

Two stroke survivors, two wheels, and a determination to reclaim life

By Julia Lyon

June 15, 2021

Steven Edgley was at home getting ready for work when he felt faint. He walked into the bedroom to tell his wife and tried to speak. No words came out.

He blinked hard. Urgently.

As his wife watched her husband, his eyes a Morse code that only he could understand, she remembered their discussion a few weeks before about a man trapped inside his body who could communicate only by blinking.

A massive stroke had left French journalist Jean-Dominque Bauby with “locked-in syndrome,” an extremely rare disorder that prevents someone from moving any muscles other than those in the eye and eyelid.

Bauby, the former editor-in-chief of Elle magazine, wrote his 1997 memoir “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” by opening and closing his left eye about 200,000 times while the alphabet was read out loud.

As Edgley and his wife spoke of the French man, he said, “That would be the worst kind of hell.”

Now, Edgley was trying to tell his wife something. And it was not good news.

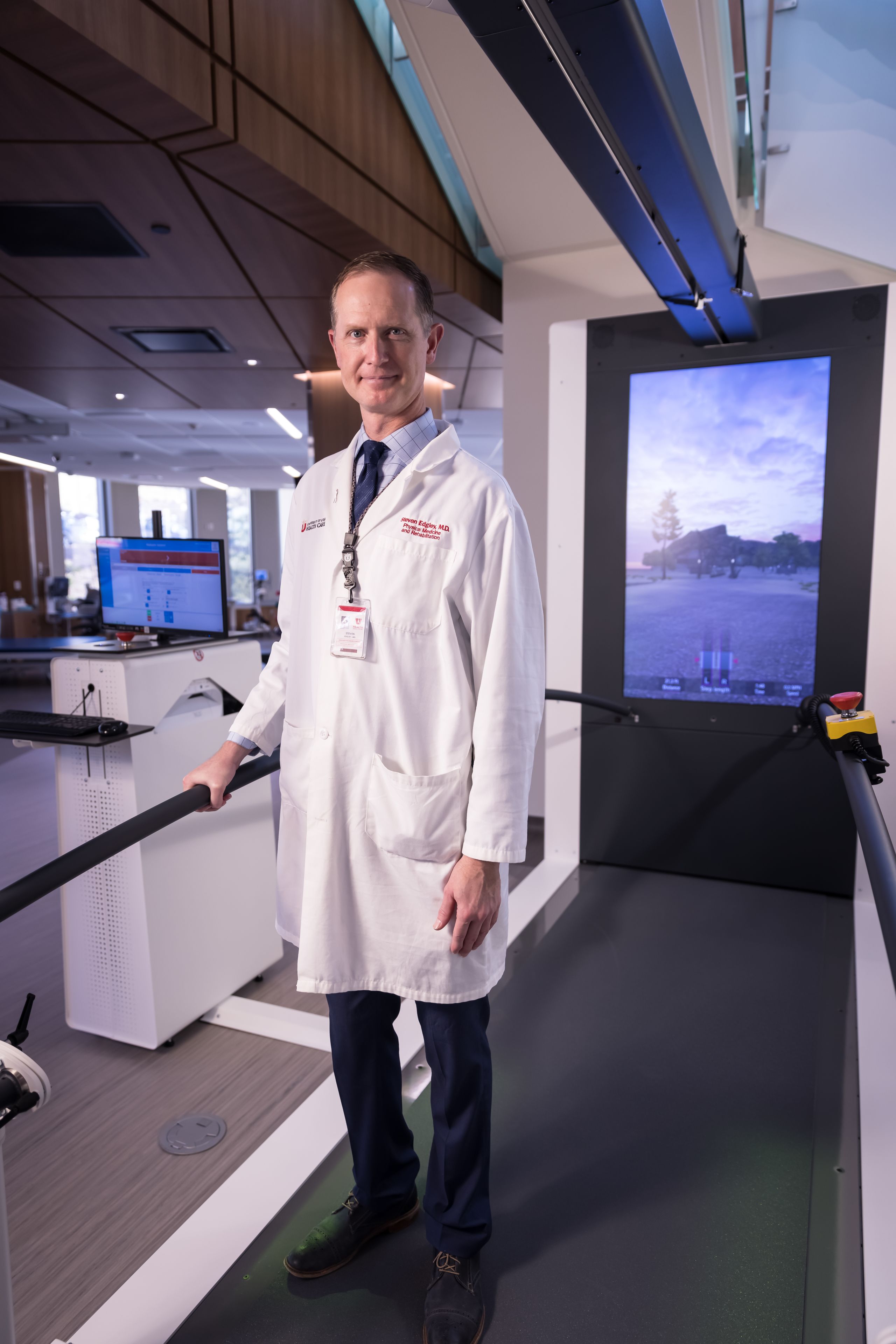

Thus began a new life that would eventually bring Edgley to the University of Utah where—as a stroke rehabilitation doctor—his story as a stroke survivor would uniquely shape his relationship with patients.

His own stroke on Dec. 7, 2001, then a 28-year-old father to a 9-month-old daughter, took away his speech, his easy athleticism and the future he had planned. But he heard about another physician who had a stroke and went on to practice medicine.

Though he never met him, there was power in the tale.

“That story gave me hope,” Edgley said. “The mind gravitates to stories.”

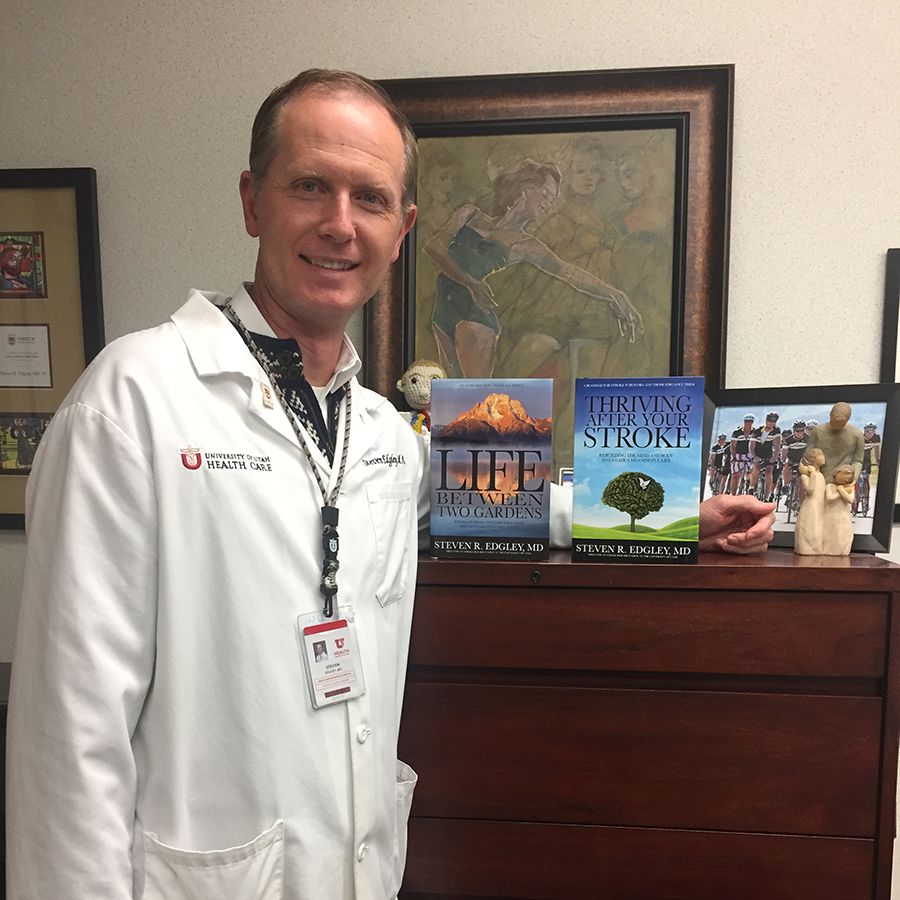

Dr. Steven Edgley

Dr. Steven Edgley

A QUESTION OF PLUMBING

After his wife called 911, she asked Edgley questions he couldn’t move his mouth to answer. The paramedics did the same. As they wheeled him into the ambulance, he wondered if this was the last time he would feel the sun’s warmth on his face.

Edgley rode to the hospital, lapsing in and out of consciousness. He understood what had happened.

The young man had graduated from medical school at Loyola University a few months before. Then in his first year of residency in ophthalmology at AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center in Chicago, he knew how devastating a stroke could be on the mind and body.

“I was trying to imagine a path forward with my right side and my speech totally gone,” Edgley said.

The original definition of a stroke essentially refers to an act by God. Like being struck by lightning, the stroke suddenly and often permanently changes someone.

Only about 360 years ago did Johann Jakob Wepfer, a Swiss doctor who performed autopsies, describe how bleeding in the brain could cause a stroke. His 1658 groundbreaking treatise, “Historiae apoplecticorum,” is still referenced today.

The clots and leaks in the brain are “a simple plumbing problem,” Edgley said.

As it turns out, his own plumbing problem related back to a common congenital variant and a slight clotting disorder that he never knew he had. His chance of having a stroke was about 1 in 10,000.

An extremely active person, Edgley had run the Chicago Marathon in the months before the stroke. He had completed several triathlons that same year. He water-skied. He played basketball. He climbed mountains.

In other words, this shouldn't have happened to him.

Twelve years later, a patient named Brian Hultman arrived at University Hospital after suffering a stroke similar to Edgley’s. Hultman was in the midst of the LoToJa—a 200+ mile bike race from Logan, Utah, to Jackson, Wyoming—when his stroke hit.

Instead of crossing the finish line, Hultman began months of rehabilitation to recover use of his right leg and arm. Edgley was his doctor, and the physician saw something of himself in his patient. He understood what it was like to be a young, athletic person struggling to regain his life. If the mind gravitates to stories, this was one he knew well.

“When you feel ready,” the doctor said. "I want to participate in finishing your race.”

A WINDOW OF MAGIC THAT IS TPA

After a stroke, the affected brain cells may be stunned, not dead. Time and normal blood flow can cause them to regain function. Some places in the brain are more prone to repair. Other centers of the brain can partially compensate for the damage.

So Edgley knew there was hope his own brain could heal. In his first hours at the hospital, he’d been given the clot-busting medication tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

He was benefitting from the stroke revolution that began when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved tPA in 1996. Today, the drug remains the gold standard medication for most strokes.

But time is critical: tPA must be given within three hours in most cases for the treatment to be effective and safe.

Now doctors can even perform a thrombectomy during which a highly trained neurointerventionist snakes a catheter from the groin to the brain and pulls the clot out. That procedure is useful for the 20% of patients with a large artery clot, which is often the worst kind of stroke.

“It can be so miraculous,” said Jennifer Majersik, M.D., M.S., a neurologist and director of the University of Utah Stroke Center. “Patients can walk out with no disability if everything aligns right.”

Stroke is one of the leading causes of serious long-term disability. As Hultman and Edgley demonstrate, someone’s age and fitness level does not make them impenetrable.

For Edgley, tPA made a difference, though the full impact wouldn’t be clear for months.

After about 10 days, Edgley was able to stand. By two weeks, he could walk with a cane and some support. By three weeks, he could speak a word.

“No,” he said, again and again.

He was thrilled. His wife was thrilled.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

“Every day is a cause for celebration in a very bleak situation,” he said, reflecting on his stroke years later.

Up until then, he’d been playing a game of 20 questions with his wife, his family, his nurses and doctor. He nodded or shook his head to respond to their queries. Now he could say a word, one of the simplest ones to pronounce.

“Yes,” would come later.

After six weeks in the hospital, Edgley was able to walk without a cane. Next began months of outpatient therapy where he would slowly regain use of his right side and his ability to speak more fluently.

Many of his short and long-term goals involved athletic achievement that would have once seemed easy. At first, he wanted to run round the track of the high school near where he lived. Edgley ran it once, twice and then four times. Next he signed up for a 5K.

Six months after his stroke, he achieved his goal. At the end of the race, he didn’t feel elated though he ran the 3.1 mile race in less than 30 minutes. He felt exhausted and overly focused on how his time didn’t match his prior athletic feats.

Recovery, he realized, would take a long time.

LIFE SAVER

Hultman doesn’t remember exactly when he first met Edgley. It was sometime in the swirl of hours and days after his Sept. 7, 2013, stroke, after an ambulance sped him from Wyoming to University Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Hultman, a deputy county attorney, was riding his bike in the LoToJa race for the tenth and what he thought was the final time. Then 45, he was hoping to spend more time with his three kids and less time training on his bike.

Brian Hultman racing the grueling 206-mile LOTOJA course (from Logan, Utah to Jackson Hole, Wyoming)

Brian Hultman racing the grueling 206-mile LOTOJA course (from Logan, Utah to Jackson Hole, Wyoming)

With 69 miles left to go, Hultman started seeing square roots and decimal points in the air. He shook his head. Then he blacked out.

He woke up to a Wyoming State Trooper asking him if he was alright. Hultman’s words sounded like gobbledygook. His hands were still on the handlebars, but he didn’t know why his bike was on the ground.

The next thing he remembers is waking up at Star Valley Health, a hospital in Wyoming, where they cut off his bike jersey and he received tPA. Hultman kept coming in and out of consciousness. He recalls looking out the window of an ambulance and then nothing until he woke up two days later.

Surgery in Salt Lake City removed three clots from his brain. As friends and family came to visit, Hultman was just happy to be alive.

Edgley, whose job as medical director of Stroke Rehabilitation at University of Utah Health is to keep medically complex patients stable enough to participate in rehab, coordinated Hultman’s care during his three-week stay in the hospital. Hultman’s right leg and arm didn’t work. His speech was slow and plodding.

Edgley, who still dreams of running as easily as he did before his own stroke, works with a team to create the rehab plan patients may use for weeks, months and even years ahead.

As with all his patients, Edgley asked Hultman to consider short- and long-term goals. Though he could barely speak and was paralyzed on the right side, Hultman said he would like to bike again. Edgley encouraged him.

Cycling on two or three wheels is an activity stroke survivors can often excel at. And Edgley knew from his own experience how important it can be for athletes to get back to activities that help them thrive.

“I encourage and promote overcoming challenges … that is the definition of strength,” said Edgley, who admits one of the highest number of patients of any doctor at the hospital. “The body will eventually break down for all of us. All of us are going to succumb to death, but overcoming challenges while we are here–Rising; Rising–is what leads to growth and success.”

At University of Utah Health, the most popular adaptive recreation activity for stroke survivors is a recumbent tricycle.

Riders wear special shoes that attach to the pedals, so the patient doesn’t have to worry about his or her weakened foot or ankle. Being connected to the bike or trike means the rider has more power with each push of the pedal.

“They can work up a sweat, doing something in the outdoors, often for the very first time since their stroke,” said Edgley.

What was different about Hultman was how he refused to let the stroke define who he was—just as Edgley had years before. The two men were both athletes, similar in age, and had experienced a similar stroke.

Though he's grateful to the doctor that removed the clots from his brain, Hultman feels that it's ultimately Edgley who “basically saved my life.”

“I’ll probably have a lifetime of having a long way to go, but I have the right attitude and I think the attitude came from Dr. Edgley,” he said.

Yet, as Hultman recovered and began training for the bike race, he was the one guiding the doctor forward.

The doctor had returned to many of his athletic endeavors, but riding nearly 70 miles with Hultman to Jackson Hole in a race was further than he had ever biked before. It required serious training.

“The patient was now helping me with something I wanted to do,” Edgley said.

THE STROKE REVOLUTION

The goal-setting mindset of an athlete helped propel Edgley and Hultman in the months and years after their strokes. But those skills that led them to achieve are not always in every patient’s natural toolbox.

“We try to get all patients to develop their skills here at the University of Utah in recovery,” Edgley said. “If you try and work hard, you will be able to improve your life.”

Rehabilitation after a stroke and recovery are two very different things.

“Rehab is really that process of learning [basic functions] again,” said Majersik, the neurologist. “Recovery is a broader term—returning to work, driving, a sexual relationship—encompassing a wider description of healing.”

The Craig H. Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital, which opened in summer 2020, focuses on both while being home to a growing number of stroke recovery researchers and clinical trials.

Stroke recovery research, historically underfunded, is now on the rise at the University of Utah and nationwide. Through Utah StrokeNet, a clinical stroke trials network, patients at University of Utah hospital as well as nine other regional hospitals have unprecedented access to the best clinical trials in stroke rehabilitation, treatment and prevention.

“Stroke research is undergoing a revolution,” Majersik said. “Our hospitals are well poised to be part of this sea change.”

Even patients outside Salt Lake City are benefiting from the University of Utah Health programs. Through videoconferencing and teleradiology, neurologists in Salt Lake City provide fast, neurologic assessment and guidance to emergency room physicians 24 hours a day to 29 hospitals in six states in the Intermountain West.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 140,000 Americans die annually after a stroke. An even larger number—more than 795,000 people—have a stroke each year.

University of Utah staff realize Edgley’s story gives him a unique power.

“He’s able to convey a level of empathy that is hard for anyone else to duplicate,”observed Chris Noren, the director of therapy for the University of Utah Rehabilitation Services.

When families learn his story, this doctor in a white coat transforms into a symbol of what recovery could look like—depending on the kind of stroke the patient has had.

KEEPING HIS FAITH

For many patients, as with Edgley, their spirituality buoys them in what may be the darkest time of their life.

Edgley, who is a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was overwhelmed by questions he initially could not articulate and questions that perhaps had no answer. He wondered if he would ever speak again.

In the days and hours that he had to think in silence, he decided he might not understand why the stroke had happened to him, but God had not abandoned him.

“God was no longer the controller of my afflictions; rather, He was that Being who hath borne our afflictions and grief, my afflictions and grief,” Edgley wrote in his memoir “Life Between Two Gardens.”“I was able to view God not as the Organizer of my suffering, but rather as the champion of my cause and eventual recovery.”

Though he had lost control of his body, he had kept his faith.

As the months passed, Edgley felt an urgency to return to work. He feared his support in the medical community—from other physicians and hospital administrators—would fade.

A six-hour cognition test showed he was mentally fit to do the job, but Edgley still struggled to speak clearly and use his right hand.

Though he regained much of the strength in his right leg and arm, lingering weakness in his right hand forced him to do most things with his left. Despite hundreds of hours of therapy, he could grip things like a water-ski handle with his right hand but he couldn’t use a pencil.

So, he looked for solutions. If he couldn’t write fast enough with his non-dominant left hand, perhaps a machine could help.

The growth of technology has transformed stroke patients’ ability to communicate. Even in 2002, in the early days of voice recognition software, Edgley’s laptop could be used to dictate patient histories rather than slowly taking notes with his left hand—or typing one-handed.

His ophthalmology residency spot already taken, Edgley considered specialties that didn’t require as much work with his hands: radiology, radiation oncology and cardiology. Ultimately, he landed on a physical medicine and rehabilitation residency, a field that encompasses everything from sports medicine to brain injury.

Working became his new therapy as he found ways to accommodate his impairment. It was treating stroke patients that convinced him that this field was his path forward.

“That ultimately propelled me to try and help people that were going through what I had gone through,” he said.

He understood the process was long, complicated and may not ultimately lead to full recovery, but it would lead to a new life.

LEARNING TO LISTEN

Salt Lake City had already played a key role in Hultman's life before it was his turn to be the patient. His oldest daughter, now 17, fainted as an infant and an MRI revealed a brain tumor. He and his wife flew with their 8-week-old baby from Wyoming to Utah where surgeons at Primary Children’s Hospital removed the growth. She received chemotherapy for the next two years.

When Hultman attempted the race that day in 2013, he wasn’t riding for himself so much as for his daughter and what she had overcome.

Now a blood clot in his brain was in the same spot where his daughter once had a tumor.

“We’re incredibly lucky to have Emmaline and I was incredibly lucky to have the results that I did,” he said. “Not everybody does.”

Some stroke survivors are in wheelchairs. Some have a significant limp or an arm curled in and useless. Some don’t survive.

“I know that sounds harsh but it’s a harsh thing, it’s a hard topic,” he said recently, sitting in the lobby of University Hospital after an appointment with Edgley.

Almost all stroke patients feel some sort of shame at being impaired or disabled, Edgley said. Shame at not being the strong person they once were. Stroke can change a person both physically and emotionally.

Hultman’s relationships have evolved since his stroke. He feels closer to his mom, dad, stepmom and stepdad, his brothers and their families.

“I love listening to people now and I didn't always love that,” he said. “I loved it if they were on my schedule.”

For the families of stroke survivors, there is life before and life after the stroke. They need support as well.

“In fact, I think they need it more,” said Hultman, reflecting on his first days in the hospital. “The person who had the stroke doesn’t know what’s going on.”

Even if the patient returns home, to work and to his or her normal activities, life may never be “normal” again.

Edgley writes books, but types them out one-handed. The most recent, “Thriving After Your Stroke,”is 65,000 words long. He hopes the book will inspire patients at the new hospital where it will be used as a patient and family guide on stroke rehab education.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

The doctor’s intellectual abilities continue to inspire Hultman, who has become a TEDx lecturer since his own stroke.

“Dr. Edgley, the words, the vocabulary—the words that he offers are just tremendous,” Hultman said.

While Hultman continues as a deputy county attorney in Teton County, Wyoming, handling cases ranging from traffic tickets to DUIs, his return to work was gradual. He's now been full time for several years.

“It was great to be back at work,” Hultman recalled. “To be part of something that mattered.”

CROSSING THE LINE

Edgley remembers how beautiful the blue sky was that day in 2015, the leaves just beginning to change color, as a group of about 30 riders biked together from the point where Hultman’s body had failed him two years before. A gentle breeze seemed to push the cyclists forward.

The ride felt effortless to Edgley while he rode with the peloton of friends and medical professionals who had played a key role in Hultman’s story. Their spinning wheels hummed together on the road. Hultman loved listening to the sound.

When they reached the outskirts of Jackson, Wyoming, people waited on almost every corner with a sign or a horn, cheering for Hultman. About the last mile before the finish line, Hultman called to Edgley to join him and his close family members as they finished the race.

“He and I planned it together,” Hultman recalled. “I would have been happy if just he and I did it—I couldn’t imagine ever doing that race without Dr. Edgley there.”

“The bike ride meant something different to each person riding,” Edgley said. “To me, it was a metaphor for why I went into medicine in the first place. I want to help patients finish their race.”

About 20 minutes later, the race winners crossed the finish line. The crowd of waiting family and community members roared as the bikers crossed the finish line.

As Hultman sees it, he and his team timed the day perfectly. “It didn't matter to me who the winners were,” he said. “I thought we were the winners.”

Edgley and Hultman were among the many riders and supporters embracing in the celebration, a celebration that left Hultman wanting more.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

Photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley

Photo courtesy of Edgley

Photo courtesy of Edgley

THE NEXT SUMMIT

As with many stroke patients, recovery isn’t a cure. Hultman continues to do occupational therapy on his right arm. He receives Botox injections, which help relax the arm muscles. His speech will progress. Cognitive challenges remain and he sometimes needs to read something a few times to make sure he's fully comprehending the text.

But the main reason Hultman comes down to the University of Utah several times a year is the man who has become as much of a friend as a doctor.

“If my appointments were moved to a different unit or a different doctor I would probably just stay up here,” Hultman said.

The two men had been planning to ride LoToJa again together until Edgley collided with a deer while going 45 miles per hour biking at dusk down Emigration Canyon in Salt Lake City in 2016.

The impact cracked nine of Edgley's ribs, dislocated his shoulder and knocked him unconscious.

The accident derailed Edgley and Hultman’s plans to ride the 2017 LoToJa relay together. “We were going to ride side by side from the beginning to the end,” Hultman said. Only the attorney took part that year.

Three years later, in the fall of 2020, it was Edgley’s turn to take on the LoToJa relay. And there, at the finishing line, was his friend.

“It was very meaningful to me that Brian was there to support me,” Edgley says. “It’s a testament to our relationship.”

The men talk of their athletic adventures on the horizon, the races yet to be finished. The summits yet to be climbed—together.

“I know he would do anything in his power for me and I would do anything in my power for him,” Edgley said.

Hultman and Edgley at Alta (photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley)

Hultman and Edgley at Alta (photo courtesy of Dr. Edgley)

FINISHING THE RACE

Written by: Julia Lyon

Edited by: Stephen Dark

Photography by: Charlie Ehlert

Banner image provided by Dr. Steven Edgley

Design by: Luat Nguyen