Esta Es

Mi Clínica

The greatest lesson medical students learn volunteering in a Midvale low-income clinic is compassion.

All Lucía Jimenez* wanted that cold, late February afternoon was to go home. For months she had held down three jobs that left her only a few hours of sleep between shifts. Those jobs, at a factory and two restaurants, paid rent and utilities for her part of a small apartment that she and her two children shared with two other Latino families in Midvale, Utah.

Sleep would have to wait. Lucía had an appointment at the one-story Community Building Community (CBC) medical clinic. She was desperate to dispel the long shadow of uncertainty her health had cast over her life. She sat in the crowded reception area, her head slowly sinking down to her chest as her eyes closed, only for her to jerk back awake and wonder yet again why they made her wait so long.

Four late afternoons and nights and two mornings a week the CBC doubled as a health care clinic where volunteer medical students saw uninsured and indigent patients. The few trees huddling leafless around the former realtor office offered little break from the bitter wind.

After Lucía had experienced bouts of intestinal pain two years ago, she had gone to several other free clinics in the Salt Lake valley in search of help. Each time, language barriers between her and the providers had made communication difficult.

The first doctor who reviewed her blood work results diagnosed failing kidneys and put her on medication she couldn’t afford. Relatives tried to support her with fresh food and encouraged her to drink lots of water.

When she went for a follow-up, a different doctor’s brief explanation of the second round of tests left her deeply confused. The anguish her first medical encounter had sewn only worsened. A friend suggested trying the CBC clinic. So there she was, waiting.

At last, an interpreter leaned into the crowded reception area and called her name. The interpreter led Lucía to a cramped corner across from an oval table where young men and women in white coats huddled over computers, went in and out of consulting rooms or talked with a grandfatherly, white-haired man. Someone took her vitals.

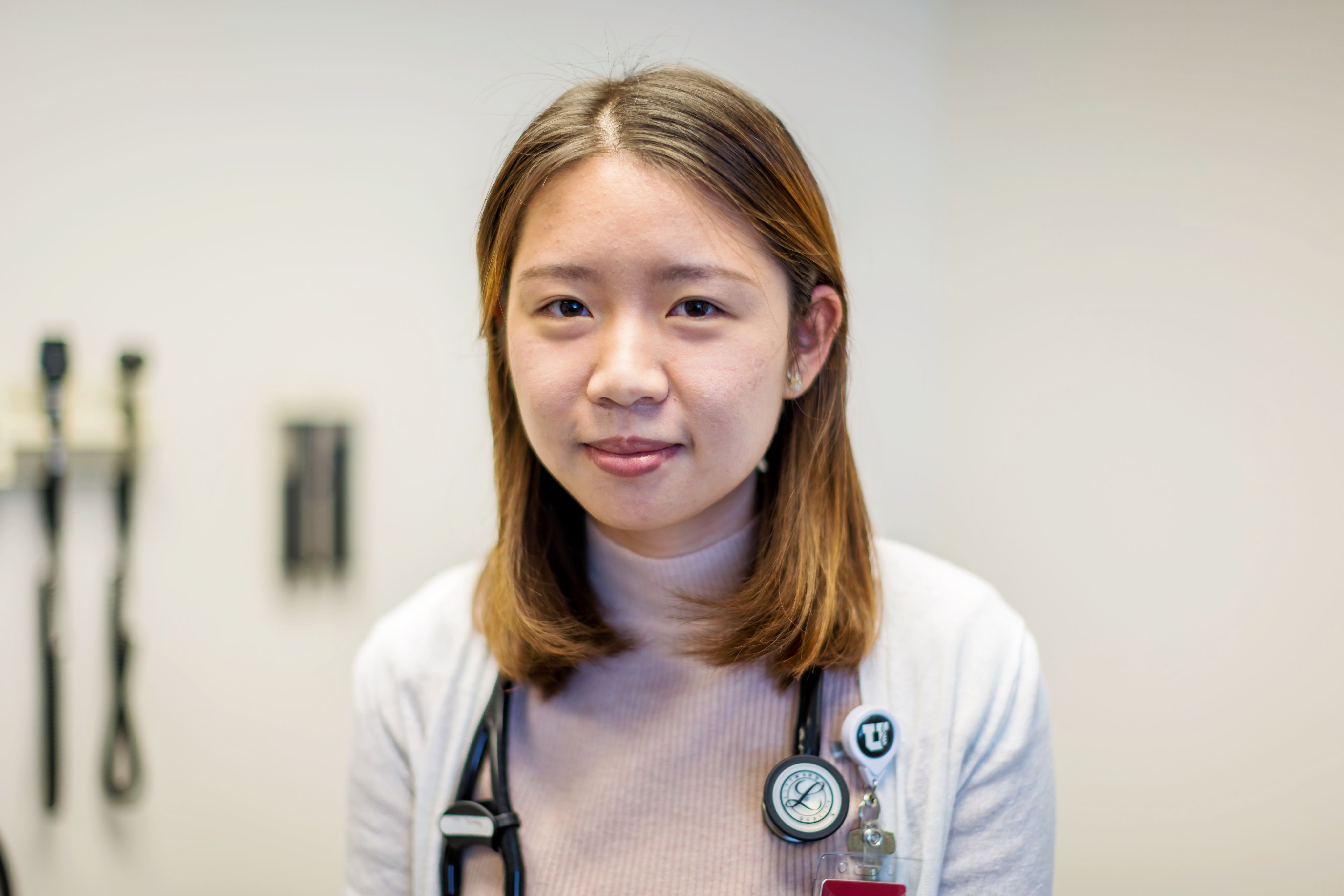

The interpreter took Lucia into a consulting room and introduced her to a 23-year-old white-coated Annie Li. A stethoscope hung loosely around her neck.

Li had begun medical school just four months ago. She had been volunteering at clinics for several years, mostly talking to patients and listening to their stories. Her time at the CBC clinic was starkly different. In those first months, she gathered information from patients to present to the attending physician, former Utah Department of Health chief and longtime clinic volunteer, David Sundwall, MD. It was a little nerve-wracking. Occasionally, Li froze in front of patients and forgot what to ask.

Li listened to Lucía’s story through the interpreter. She could see the strain in her features and the effort she made to stay awake and felt bad she had had to wait so long. The clinic was overwhelmed that late afternoon, one of the students delayed by traffic.

Something else struck Li: how close Lucia’s story was to her own mother’s. Li, her twin sister, and their parents had emigrated to the United States and Utah. They had left China when the twins were only one for their father’s new job as an electrical engineer in the Salt Lake valley.

When Li was seven, her mother was diagnosed with lupus. Like Lucía, Li’s mother had struggled to navigate the complexities of the US health care system. What had proved particularly difficult for her was understanding the lab tests. While she was conversationally fluent in English, the lab terminology was impenetrable.

Lucía showed Li a sheaf of paperwork going back more than two years. “No one explained to me what these tests mean," she said in Spanish.

Li saw how much not knowing if she might eventually need a kidney transplant or dialysis weighed on her patient. Not that Lucía believed she could ever afford such medical miracles.

Lucía’s predicament brought back Li’s memories of her mother huddled over lab results at the kitchen table, worry etched into her features, lips moving silently as she tried to pronounce words she did not know.

INVISIBLE NEED

Lucía Jimenez is one of 3,000 to 5,000 people who annually depend on the CBC for dental and medical services. The majority, but far from all, are Hispanic.

The need for such services is underscored by the extensive list of socio-economic, health, and other issues that dog Midvale’s minority communities. Midvale’s population is 24.5 percent Hispanic and 11.7 percent other racial minorities. It’s one of the most diverse communities in both Salt Lake County and Utah.

The 2021 Utah Health Improvement Index gives Midvale a rating of 120.1. That classifies Midvale as “very high, poor,” meaning that, according to the report’s compilers, there’s “a greater need for improvement in social and economic areas impacting health.”

It’s a population that faces severe health inequities. Health equity, according to the Center for Disease Control, “is achieved when every person has the opportunity to ‘attain his or her full health potential’ and no one is 'disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances.’”

Digging a little deeper into the index’s findings, it’s not hard to see why Midvale's population faces so much adversity when it comes to being healthy. In comparison to averages in Salt Lake County and Utah, Midvale claims the highest percentage of households with single mothers and the highest percentage of poverty. At $60,000, its median household income is one quarter less than Salt Lake County’s at $80,000. Rates of suicide, cancer, stroke, heart disease, and drug-related deaths are all higher than county and state averages.

But how to help such a beleaguered community, especially when many live in the shadows because they are undocumented? The answer the CBC found, says current Midvale mayor Marcus Stevenson, was to build trust.

That began with developing a panoply of services. From classes on parent and child communication within conflicting cultures, teen pregnancy, emotional therapy, and legal support to vaccines, a food bank, and violin classes for children. Think of it as a support system for underprivileged and often otherwise invisible Latino families on the margins of Utah life.

Building trust between the one-time municipal office turned independent non-profit in 2013 and a long-marginalized community wasn’t achieved overnight.

THE VALUE OF PREVENTIVE CARE

Outside the CBC’s former offices in the old Midvale municipal building is the Centennial Bell, cast and mounted in 1996 to celebrate 100 years of Utah independence. Mauricio Agramont is the CBC’s tireless executive director, who deploys ingenuity and humor in the face of constant resource and funding challenges to achieve his vision of improving life for underprivileged Latinos in Utah. After years of hard work, Mauricio started hearing Latinos urge each other, “Go to la campana. You know, the big bell downtown? That’s where you can get help.” He knew the CBC had truly arrived.

By providing basic services at the beginning, Mauricio and his small, entirely Latino-staffed team sought to build bridges with the community that would allow them to encourage people to also get preventive health care.

Impoverished rural Mexicans do not seek out health care. “If you have to choose between paying the rent or getting your kids clothes for school, or expensive nutritious food or the dollar menu, it’s clear what you’re going to do,” says Mauricio. And one of those choices was putting off seeking health care until a life-threatening condition left you with no choice but to go to the ER.

“You can prevent those emergencies with good care,” says Wayne Samuelson, MD, now the former dean of the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine at the University of Utah.

“When somebody dies of complications from diabetes, they’re usually blind, have kidney failure, heart attacks. They’re feeling like they can lose limbs,” Samuelson says. “Preventing that is straightforward. It’s something we can do with people that are learning how to be doctors.”

Samuelson’s passion for the CBC’s core mission led to him being its first long-term volunteer medical provider. He led the way for med students who have been volunteering at the clinic since 2013.

What allowed them to provide services was that key ingredient of trust, says third year medical student and one of the recent leaders of the student-clinic, Christina Necessary. “They have built up a sense of trust in the community through all of their programs. And so I feel they lend us that sense of providing a safe harbor that they have already built with the community.”

Each year, students build upon the changes and successes of their predecessors. In the clinic, students learn what theory and classwork can never teach them: the stresses, challenges, and rewards of serving those most in need.

Those rewards aren’t monetary, notes Samuelson. “Over the years, what I’ve tried to do is to let medical students and people in training feel how great it is to do the right thing for the right reason.”

AGENTS OF CHANGE

The story of the CBC and its health clinic is in great part a chronicle of the evolution of a relationship—based on compassion—between those offering help and those in need. But it’s also a recognition of the remarkable opportunity that a collaboration between the CBC and its student and provider volunteers has created.

In 2023 the SFESOM unveiled a new curriculum that includes volunteering in clinics as a key component of all four years of medical training. Students work under the supervision of volunteer, board-certified, attending physicians at five clinics: Midvale CBC, People’s Health Clinic in Park City, and three Salt Lake City clinics, Fourth Street Clinic, Rose Park Clinic, and U of U Health South Main Clinic.

But along with excitement, students, providers, and University of Utah Health administrators have had concerns about the endeavor: Will it impact the special culture of the clinics? What happens when volunteering becomes mandatory in a curriculum?

“It’s uncharted territory,” says Sara Lamb, MD, vice dean for education at the medical school. But it’s a journey she insists that the U, its students, and leadership have a moral obligation to pursue.

This new student-led clinic network is a first not only for the U, but perhaps for academic medical centers nationwide.

“Nobody has done this in medical schools that we can tell,” says Lamb. “While teaching hospitals have volunteer student-run clinics, no one has actually integrated experiences for students across the four years of medical school into the core of their program. It’s something that we do as a mission of the school. All our students are going to have a longitudinal relationship with all five clinics for the entirety of their medical school experience.”

Lamb hopes students emerge from this experience with a desire to not just “do no harm,” but to bring about change.

She remembers a 2019 Association of American Medical College’s meeting where attorney-writer Bryan Stevenson spoke movingly about Just Mercy, his memoir of working as a civil rights attorney defending a man facing the death penalty. His talk emphasized the importance of not backing away from challenges such as a broken criminal justice or health system but rather getting closer and of how fundamental compassion is to changing an unjust society.

Stevenson’s speech moved Lamb. Sitting in the audience, she struggled to compose herself and left the auditorium in tears. It was like a revelation. She realized this was what students needed. Not to keep themselves at a distance only focusing on matters relevant to passing board exams, but to see close up the value of caring for those without access.

Lamb wants students to learn the biggest lesson that the Midvale CBC clinic and similar initiatives have to offer: the value of compassion in medicine.

As she grappled with the enormity of change they were trying to bring to the curriculum, what inspired her was a hope that integrating clinic volunteering through the four-year curriculum would allow medical students to graduate as something more than cogs in a broken system.

Lamb hopes students will recognize barriers to access and become change agents on a global level. She believes health care should be seen as a basic human right. “You should have a right to get the services you need to be healthy,” she says.

A MAYOR’S DREAM

Bordered on the west by the Jordan River and the Brigham Junction economic center—with its myriad corporate offices and high-end townhomes—and on the east by the sprawling Fort Union shopping center, Midvale stands at the geographical heart of the Salt Lake Valley.

Back in the 1940s, Midvale’s Main Street offered such gems as the once-largest soda fountain in the country at Vincent Drug Store. Dozing under a canopy of trees, it remained—through good times and bad—an icon of small town America. From the 1970s through the 2010s, numerous films and TV shows were shot there, ranging from The Sandlot to Stephen King’s The Stand.

The construction of I-15 and I-215 through the heart of Midvale turned Main Street into a ghostly echo of itself. And the decline of local steel and mining industries gave the small town an economic and sociological beat-down it still struggles with, despite robust urban renewal and development on its borders.

In the mid-1990s, Midvale’s Latino community was beset with extremely high rates of unemployment, suicide, infant mortality, and teen pregnancy. Community members had little to no access to medical or dental care. Midvale’s response, in 1998, was to launch the CBC initiative.

Mayor Joanne Seghini knew she needed a Latino to take the CBC from its initial discussions and fact-finding role to direct action. In 2004, she hired Mauricio Agramont.

Born and raised in Bolivia’s capital city, La Paz, Mauricio attended the University of Utah. He studied urban planning and married a Utahn. After seven years back in his home country, Mauricio and his wife returned to Utah to train in managing nonprofits. At the Fourth Street Clinic, he learned about poverty and homelessness. At the Association for Utah Community Health he learned about safety networks for low-income, uninsured families. During this period, he saw a stark need in Utah for health care among first generation Hispanic immigrants and decided to stay.

When Seghini offered Agramont the reins of the CBC, he jumped at the chance. One key challenge he faced was the highest infant mortality rate in Utah at 11.6 per 1,000. Another was the highest teen pregnancy rate among 64 Utah municipalities. Children as young as 11 were contracting STDs. To deal with these issues, Mauricio needed people who could relate to those he sought to serve with both humility and understanding.

At an HIV prevention training in Utah in 2007, Mauricio met a young Colombian who struck him as the kind of person he was looking for to help him build the CBC.

Born into poverty in Bogota, María Consuelo Cala-Beltran studied psychology at the National University of Colombia. She worked for UNICEF-Colombia with children and youth displaced by armed conflict between guerillas and paramilitaries in often dangerous parts of Columbia’s northern territories. In 2001, she moved to Utah, where her husband had taken a position with a mining company.

Mauricio hired her as his assistant.

“He has the dream. I make it happen,” says María Consuelo. “We perform miracles when we see the same way.”

One of the early miracles was tackling the high rate of teen pregnancies. Within six years, partly while working alongside Planned Parenthood, Midvale went from being highest in the state in teen pregnancy to 15th.

A KNOCK AT THE DOOR

Before expanding access to health care for Midvale’s Latinos, Mauricio first had to get them to trust the CBC. To achieve that he launched Neighbor to Neighbor.

He says, “My idea was always that our health outreach workers would get people in through services, such as a food bank, legal, education, etc., then channel them to the medical clinic.”

He hired Ramona Velasquez Hernandez and others from Mexico and Central America as CBC advocates.

In Ramona, Mauricio had someone who spoke the language of the rural Mexican poor. Growing up in Jalisco, Ramona’s parents had been too poor to feed all their children. They gave her to another family to raise as a servant. She grew up to be a sobadora, a healer with skills—taught to her by her aunt—that mixed homeopathy and massage techniques.

She married at 25 and followed her husband to the US, crossing the desert in 1999 and settling in California. They raised two boys and eventually moved to Midvale, where her husband cleaned offices and she worked in schools. They lived in a large apartment block where many rural Mexicans sought out her healing skills. She walked mile after mile visiting the sick in her tightly knit community.

As a CBC outreach worker, Ramona talked to anyone who opened the door about the nonprofit and its nascent dental and medical clinic. If someone answered her knock at the door, she didn’t say “Let’s talk about hypertension,” but rather, “Hey, how are you?” and invited them to visit the CBC with their children. They came because when they looked at her and listened to what she had to say, they saw and heard themselves.

A SACRED DUTY

During 2008 and 2009, the CBC had a clinic set up in a motorhome parked by their office. It was open half a day a week and saw 60 to 70 people. But Mauricio knew the scale of need was much larger. Over the next six years he talked to several federally-funded community health centers. One after the other they set up clinics in the CBC offices.

“We thought it was a long-term solution,” Mauricio says. “It turned out to be a very short term one.” In each case the need for care was so great that what help the health centers could offer was immediately tapped out and they closed.

“The only way to ensure access to health care is to open a clinic ourselves,” he had told María Consuelo.

“You’re crazy,” she replied.

“We can start small,” he said.

As badly as the community needed medical care, the demand for dental care was just as great. Mauricio recalls some people taking matters into their own hands. “They couldn’t stand the pain, so they did the extractions themselves,” he says.

Dental clinic located inside Midvale CBC

Dental clinic located inside Midvale CBC

Floyd Tarbet, DDS, a retired dentist, offered to provide direct services of fillings and extractions. Finding a partner to add general practice health care to the clinic proved more challenging. None of the local health care institutions he approached were interested.

But in 2010, the office of Health Disparities at the Utah Department of Health called to say Evelyn Gopez, MD, at U of U Health, wanted to open a small community clinic.

The always forthright Mayor Seghini had her own ideas. “I think the medical school owes it to the community to have your faculty come out here and take care of the people of Midvale who are poor and uninsured,” she told Gopez.

Seghini’s idea landed on Samuelson’s desk. He liked it, but volunteering alone was not sustainable as a project foundation. His vision was to start a community clinic to treat uninsured patients and have students do the hands-on work with populations they would otherwise be unable to help.

Samuelson told Seghini that students would volunteer to see patients at the clinic, but not if they were told it was long term. “Nobody would raise their hand,” he said.

He suggested instead making it a teaching site where medical students and those studying other health care disciplines could get clinical experience. The mayor agreed.

THE THERAPY OF CARING

Samuelson traces his passion for medicine as a noble calling to a mentor at medical school. “He convinced me that being a physician was a sacred duty.”

Samuelson felt if he didn’t put in some sweat equity at the CBC, students wouldn’t volunteer. In June 2011, he ran a pilot clinic at the Midvale Middle School with three exam rooms.

He quickly learned that patient safety was paramount. When the first patient came in, the volunteer interpreter told Samuelson, “I’m going to explain some things to this person.”

Nothing was being recorded, she told the patient. Samuelson had no connection with the police, and no one would be reported to any organization. The intent was to ensure patients felt safe telling the doctor anything within the walls of the exam room.

“Got it,” Samuelson thought.

Several evenings a week he would drive down from U of U Health’s campus and park in the cramped CBC parking lot. When he stepped into the CBC’s offices, everything else in his life melted away.

“This is my therapy,” he would tell anyone who asked what he felt about working at the clinic. He could focus on people who he cared about and, indeed, felt they cared about him too. Ramona would bring him homemade tamales, and he and Mauricio became firm, enduring friends.

Volunteer students came and went, but Samuelson was the primary physician. Sometimes he couldn’t help but get a little possessive about it.

“When a patient is seeing a doctor for the first time in their life, and they are older and have been living with stuff you can fix, and then the patient shakes your hand and hugs you and says, ‘Thank you.’ You know, wow! That feeling has got to be better than any drug,” Samuelson says.

The Midvale clinic introduced him to a new world. Many patients were first generation undocumented immigrants. They were trying to stay invisible by not seeking out resources, staff explained to him. They worked construction, cleaning, fast food, and in service industries for cash in hand. Some had fled cartel violence in their home countries. They would have preferred to stay there if violence hadn’t driven them out.

“I want to have a better life for my children. My life is very, very hard,” they would tell him. Inevitably they brought with them the pain and suffering they had endured in their homelands or on the all too often harrowing and heartbreaking journeys to reach the United States.

The traumatic violence or loss of loved ones induced migraines, stomach pain, and muscle-related stress issues. Nevertheless, their principal goal was to finish paying the month’s rent, food, utilities. “My health is not my goal,” they said.

In some immigrant cultures, staff said, if they don’t go to a doctor for 20 years, they think it means their health is good.

For Samuelson the clinic was life-changing. The patients at the clinic took him into their lives. He saw firsthand how hard they worked, how much they cared about their families. Nights at the clinic left him utterly exhausted. Yet he felt mentally, emotionally, and spiritually invigorated.

And for CBC staff like Ramona reaching out to potential patients, the evolution of the clinic idea to reality spurred them on. Ramona wanted people to feel the pride she felt that their community had brought this clinic into being.

“Esta es mi clínica,” she told anyone who asked about why she worked so hard for the future of the Midvale clinic. “This is my clinic.”

“SKIN IN THE GAME”

After hearing Gopez plead to U of U Health leadership for volunteers at the clinic, retired family physician David Sundwall, MD, joined the CBC as its second volunteer attending. “I can work that into my schedule,” he thought.

A life-long volunteer, he had spent 17 years at a Catholic-run federal city shelter in Washington DC that slept 1,200 people, mostly black men who had left prison to find little to no opportunities to build new lives.

Each low-income or indigent clinic Sundwall has volunteered at sees medical issues unique to the patient population. In the CBC’s case, Sundwall knew Hispanics had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, which included conditions such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. These conditions all raised the risk of heart disease and other serious health issues.

Initially the clinic was free, but after a modest co-pay was introduced, the number of patients seeking appointments at the clinic surprisingly went up. “Patients wanted to have a little skin in the game,” Sundwall says.

Still, CBC patients couldn’t afford most drugs. So Sundwall helped them find discounts. He emphasized to students the need to be sensitive to the impact of health care costs and to seek to provide care in the most affordable way possible.

After the CBC lost its office space at the Midvale Middle School when it was scheduled for demolition, Mauricio found a former realtor’s office next to a Trax station. It had enough space for three exam rooms, a common dental area, and a small conference room. The young couple who owned the 3,000-square-foot property reacted positively to the idea of the CBC making the space its home and gave them a good deal on the rent.

Midvale CBC waiting room

Midvale CBC waiting room

LAST MEDIC STANDING

In March 2020, as COVID-19 burst upon Utah—and the world—the clinic closed, but only for a week. The CBC’s medical providers insisted to local authorities they needed to stay open for emergency services, be it dental extractions, medical issues such as infections requiring antibiotics, and prescription refills. If they were open, their clients would stay away from emergency rooms in the valley and the possibility of exposure to the virus.

Except for emergency services and the ICU, University Hospital and U of U Health had closed for nearly all medical procedures and treatment unrelated to the pandemic. This meant Samuelson and medical students could not attend the clinic for many months. But Sundwall insisted on going.

“I was the sole physician provider for a while,” he says.

Another key operative at the clinic during the pandemic was a vivacious, high-energy newcomer. Magali Velasco hailed from Argentina. She worked the phones, calling a list of former and current patients, checking on those who couldn’t get out, and contact-tracing positive cases of COVID-19 for the health department.

Many of Utah’s Latino community work in essential industries such as meat packing and cleaning in hospitals that had to continue during the pandemic. With many families living in cramped, shared spaces, there was constant concern among service industry workers of bringing the virus home.

When Magali contacted people to see if they needed rental assistance, vaccines or help with schoolwork, many didn’t want to go to the hospital. They feared dying there.

At the same time, María Consuelo worked tirelessly to keep the clinic open with her son’s help. As concerned as they were about taking the virus home, she told her husband, “The community needs us, so they are first.”

Towards the end of the pandemic, María Consuelo brought in the student leaders to set up COVID vaccination and flu programs at the clinic. The student leadership also focused on setting up the clinic’s first in-house lab to provide not only COVID and flu vaccines, but other children’s vaccines too.

“The students came to help not as part of the clinic, but as part of community outreach,” Mauricio says.

After decades spent trying to address community needs, Mauricio still saw poverty in Midvale at levels he’d expect in a developing country. As the pandemic waned, the CBC opened a food bank. Initially just 20 families came seeking supplies. Within a few months, that number had quadrupled.

The pandemic took its toll on Ramona. In her late 70s or early 80s—no one, including her, knows her real age—lockdown restrictions barred her from entering apartment buildings to visit community members, as she had done every day for years.

Magali absorbed some of Ramona’s duties, including taking students to outreach health fairs or attending parent-student conferences. They would take a table of information on health services, check blood pressures and BMI, and offer pre-diabetes testing.

Magali learned how charity care works, who accepts the indigent and who doesn’t, when they should go to primary care, to the ER or urgent care, and how patients can avoid a $3,000 bill.

“She doesn’t only know where patients can go but guides them so they don’t end up with a bill they can never pay,” Mauricio says.

PRESERVING THE VOLUNTEER SPIRIT

Lamb traces the seeds for the CBC clinic becoming part of a model for a first-of-its-kind medical school curriculum to a medical school town hall in spring 2018. Med students had expressed frustration that the academic medical experience had no place for direct clinical work. Their frustration had even led some to question why they had decided to go into medicine in the first place. It set her thinking about how to leaven medical school with real-life patient encounters.

University of Utah medical student Christina Necessary cares for pediatric patients

University of Utah medical student Christina Necessary cares for pediatric patients

As time went by, those seeds began to sprout.

During a 2021 call to Samuelson, Lamb floated an idea. “What do you think about Midvale being part of clinical-skills experience and clinics like that becoming a core of what we do as a school?” she asked. “Not just for students who opted in, but for all students.”

As Lamb, Samuelson, and others fleshed out the initiative, faculty and students expressed concerns about not taking advantage of patients and ensuring high quality of care. The last thing Lamb wanted was for it to appear that the school was pushing medical students on vulnerable people who otherwise didn’t have access, or to give them suboptimal care.

There were other challenges, too. They included scaling clinical time so that it remains a meaningful experience for students and ties closely to the core of their educational program, maintaining student interest and investment, and convincing skeptical faculty that students taking longer with patients who are short on time doesn’t disadvantage them.

University of Utah medical students consult with a patient

University of Utah medical students consult with a patient

CBC staff and patients do not share those same preoccupations about the program, Lamb points out. Rather, they are excited and inspired by what’s happening.

But one fear voiced by students who have volunteered at the clinic has given Lamb some pause. Would making the student-led clinic experience an expected part of medical school ruin the volunteer spirit?

“That intrinsic motivation and drive to want to serve is part of this experience,” Lamb says. “That some students will do it to check a box, that it will be more transactional, more about their own professional development and growth than the people who need us to help them get the health care they need, that’s something we do not want.”

“THIS IS ALL I HAVE”

That foundational volunteer spirit animated the February 2023 evening clinic when Li was listening to Lucía Jimenez. Another student was in charge that night. Zachary Moore, a 25-year-old first-year with a passion similar to Li’s.

Born in California, Moore is a Spanish speaker. He served a two-year mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Mexico City and nearby Toluca. People he knew there expressed frustration with a health care system with many providers, but few who patients felt had adequate training or resources.

He met hundreds who had not seen a doctor in many years. “They didn’t have a prayer to access care,” he says.

When Moore returned to the US, he volunteered as a medical interpreter. He wanted to maintain his Spanish and also continue his mission-volunteering ethic. At one clinic he met a patient who was scared about the cost of her care. She didn’t speak English, had recently emigrated, and was experiencing symptoms of advanced diabetes and diabetic damage.

“Showing him a $20 bill, she had said, “This is all I have. Will this cover it?”

Moore told her there would be no bill and that her medications would be at a substantial discount. Still, her vulnerability and anguish left its mark on him.

Two weeks after starting medical school, Moore signed up to volunteer at the CBC. In class, he learned the basic physical exams and practiced them on standardized patients who had been vetted to be “normal.” Conducting physicals on Midvale patients was a different experience.

“It’s really valuable to come here and to not have someone that already knows what you’re going to do,” he says. “To have the interaction with patients as we take a history, as we do the physical exam, is invaluable. There’s no substitute for it.”

THE BEARER

OF GOOD NEWS

In a CBC exam room, Li reviewed Lucía’s three sets of lab results and an X-ray of her kidneys.

Lucía stared into the distance, glassy-eyed with exhaustion. “No one explained what they meant,” she said in Spanish, her face drawn with worry.

With her little English, she had been unable to insist someone talk them through. And when yet another doctor she met for the first time at another free clinic had wanted different tests, communication had broken down further.

Like Lucía, Li’s mother had focused only on what the results identified as irregular or abnormal, without knowing what it really meant. In many cases, Li knew, it didn’t necessarily mean anything was seriously wrong.

As she reviewed Lucía’s pages of tests and results, Li found that the first set of labs indeed displayed some alarming numbers. But Lucía’s turning to a healthier diet and drinking a lot of water had borne fruit. The subsequent results showed that her kidneys were good. Better than good, actually. The tests revealed a picture of overall health.

Careful not to use strong language, as she was only a first-year, Li tried to convey to Lucía that she did not think the results were as bad as Lucía believed. She would consult with Sundwall, she said, and then he would be in to see her. The attending reviewed the results and agreed with Li’s assessment. Lucía’s kidney function was improving.

Sundwall sat beside Lucía and touched her hand reassuringly. While the test results weren’t completely normal, he explained through an interpreter, they weren’t bad enough to require seeing a specialist.

He spoke reassuringly. “We need to continue monitoring you to understand what is happening. Okay?”

“Thank you,” Lucía said in faltering English, and Li smiled softly.

Lucía* smiled back. She zipped her jacket. To the east, the setting sun had broken through the clouds to glaze pink-orange the snowcapped mountain peaks of the Wasatch.

Lucía didn't seem to notice. All she could think about was that she had her future back, finally unburdened by medical confusion. Relief smoothed away the lines of exhaustion on her face as she walked home to her children.

*Reporter Stephen Dark spent two weeks interviewing staff, patients, and providers at the CBC Midvale clinic. During that time, Dark, who speaks Spanish, volunteered as an interpreter for patients and providers. Lucía Jimenez is a composite drawn from several patients he met at the clinic.

ESTA ES MÍ CLINICA

Story by Stephen Dark

Concept by Stephen Dark and Aaron Lovell

Design:

Laurie Robison

Photography:

Charlie Ehlert

Stephen Dark

Editor, Publisher:

Aaron Lovell

Thank you to the City of Midvale, the staff and patients of Midvale CBC, and faculty and students of the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine for their time and contributions to this story.