A CELEBRATION OF LIFE

Edward Bowersox Clark, MD

1944-2022

Remembered at the University of Utah by those who knew him: An inspiring leader, colleague, and friend

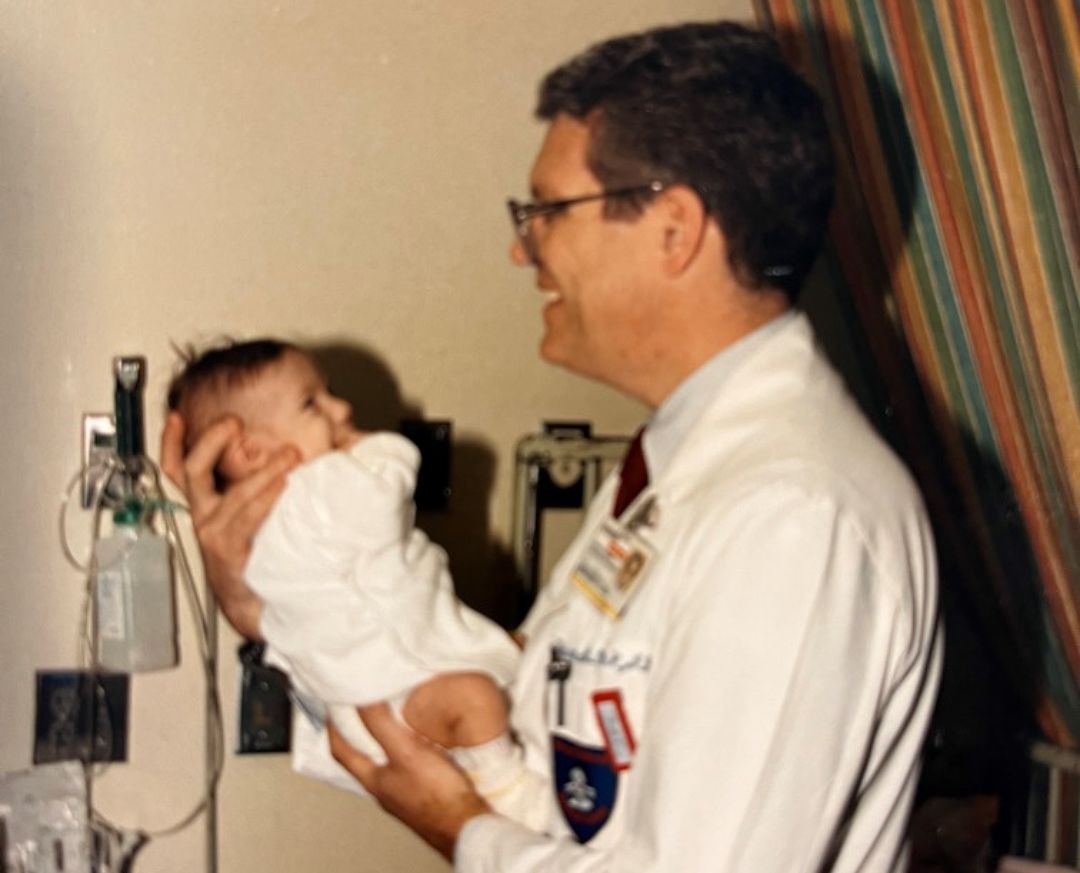

Edward Bowersox Clark, MD, a shining light in the firmament of University of Utah Health, died at home in Salt Lake City on March 8, 2022. For 26 years at University of Utah Health, he served as a noted clinician, teacher, administrator, research scientist, mentor, and friend. He was devoted to advancing health care for children and strengthening the communities where they grew up. Beyond his immeasurable influence at the U, in the state of Utah, and throughout the Mountain West, Clark was an iconic figure in American pediatrics. He insisted that a great society takes care of its kids. Clark's favorite phrase was,

“The child first and always.”

A WORLD-CLASS LEADER

Clark, a pediatrician and pediatric cardiologist, came to University of Utah Health in 1996 as chair of the Department of Pediatrics and chief medical officer of Primary Children’s Hospital (PCH). He served in those positions for 22 years. Angelo Giardino, MPH, MD, PHD, FAAP, who followed Clark as chair of pediatrics, points out that seven is the median number of years to be a chair in academic medicine.

“He was a transformational figure for the department,” Giardino says. “He more than tripled the size of the department and essentially filled in any gaps that we had in terms of a comprehensive inventory of all of the different divisions, sections, programs, and initiatives that a world-class department of pediatrics should have.”

Today, the Department of Pediatrics at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine (SFESOM) has more than 300 faculty members. “Ed recruited probably 100 faculty over the course of time,” says Mike Dean, MD, MBA, vice-chair for research in the Department of Pediatrics and Clark’s longtime colleague. “And then another 100 faculty that are adjunct community pediatricians.”

One thing that drew Clark to Utah was the enormous potential of a collaboration between Intermountain Healthcare and U of U Health. Clark saw that synergy between one of the nation’s largest health systems and an academic medical center where you could bring together research and clinical care in an unprecedented way.

Clark built critical bridges between Primary Children’s Hospital and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. Here he is pictured with Katy Welkie, RN, MBA, VP of Children's Health & CEO of Primary Children's Hospital at Intermountain Healthcare.

Clark built critical bridges between Primary Children’s Hospital and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. Here he is pictured with Katy Welkie, RN, MBA, VP of Children's Health & CEO of Primary Children's Hospital at Intermountain Healthcare.

As Clark began leading the pediatrics department at the University of Utah and serving as CMO for Primary Children’s Hospital, he also started building bridges with Intermountain Healthcare. “It’s very unusual to have a department positioned almost as Switzerland, because Intermountain and U of U Health are competitors,” Dean says. “But Ed realized the opportunity to improve health care for kids on a statewide and regional basis, because we get a lot of kids from the surrounding states, and it was a big challenge. But he did it. Ed connected two distinctly different health systems together in a very meaningful way. It was a major accomplishment. I’ve never worked in a hospital where the culture is better than it is at Primary Children’s.”

“Ed connected two distinctly different health systems (U of U Health and Intermountain) together in a very meaningful way. It was a major accomplishment.”

—Mike Dean, MD, MBA, vice-chair for research in the Department of Pediatrics

The collaboration brought national recognition to the Department of Pediatrics and the University of Utah, attracted brilliant residents and faculty from across the country, and strengthened work in all the department’s missions. With the alliance, Clark brought more providers and subspecialties within the pediatrics divisions.

Clinical advances included a consolidated kidney transplant program, capabilities for rapid genome sequencing, and the opening of the Cystic Fibrosis Center, which ranks among the highest in the country. Under Clark’s leadership, the pediatric residency program was enhanced with trainees more fully integrated with PCH.

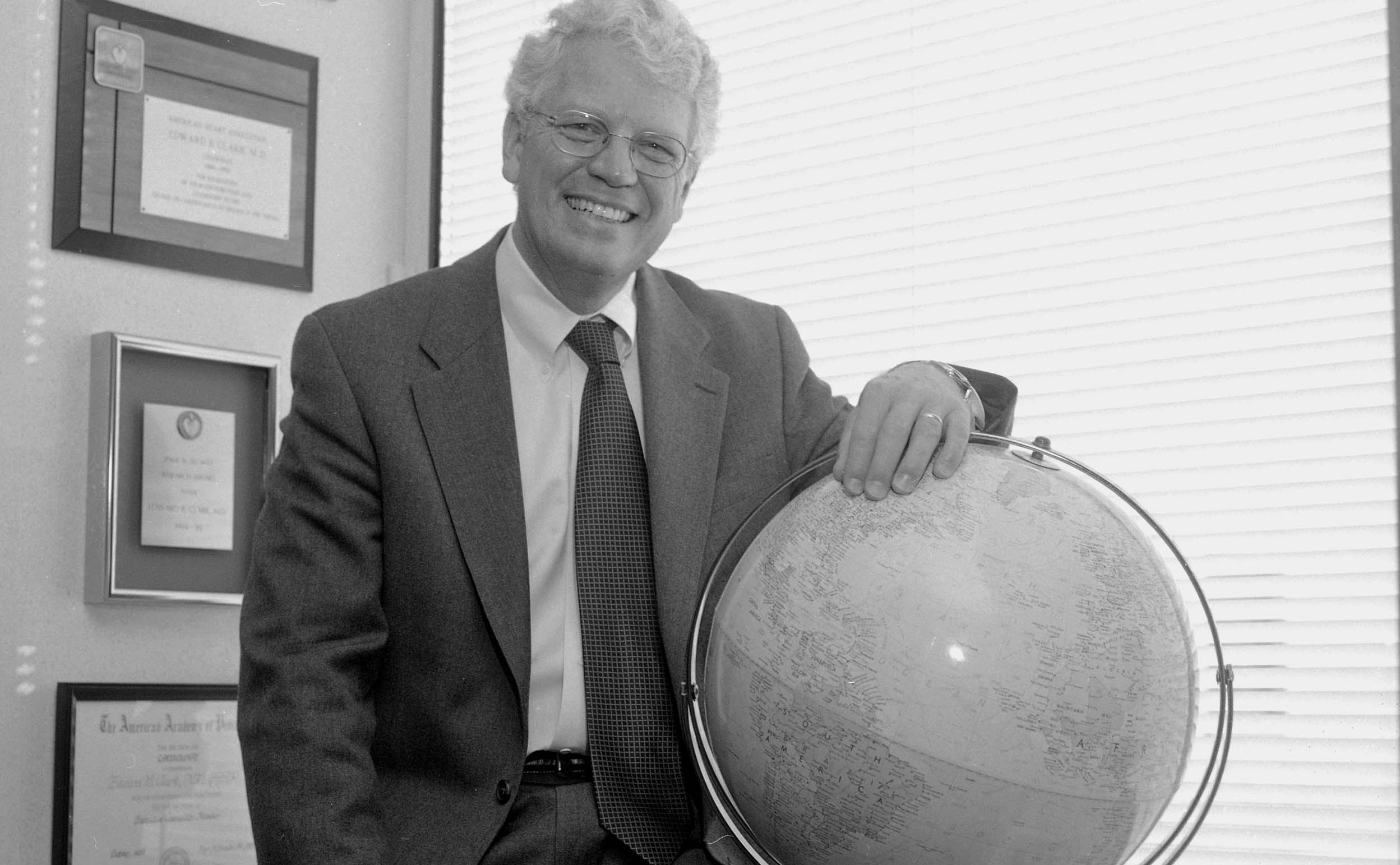

A PURE ACADEMIC

Clark was fundamentally an academic physician, Giardino says. “He knew science is at the root of what we do. The problems that our patients confront are things that we can study. Essentially, an academic physician feels that every patient treated is a patient we should study to advance knowledge. We should collect our experience with those patients that we’re treating and rigorously figure out what’s working and what’s not.”

Clark envisioned communities of scientists working together to make discoveries that would help improve the care of children. To help realize that goal, he appointed Mike Dean as the department’s vice-chair for research. “Ed and I both knew that if we didn’t have any pediatric scientists, we wouldn’t have any progress in pediatric therapeutics and understanding of the pathophysiology of pediatric diseases,” Dean says.

Clark was deeply committed to research and discovery and helped support hundreds of studies during his tenure. Pictured here is Krow Ampofo, MBChB, who took a lead role in a study that examined pneumonia in children and the need for better diagnostic tools to provide the right treatment.

Clark was deeply committed to research and discovery and helped support hundreds of studies during his tenure. Pictured here is Krow Ampofo, MBChB, who took a lead role in a study that examined pneumonia in children and the need for better diagnostic tools to provide the right treatment.

While Clark was chair, Dean began the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) to establish connections with national research networks and open additional opportunities for discovery. The DCC has coordinated almost 100 pediatric studies nationwide with more than 70 different institutions and has generated 300 papers during the past 15 years.

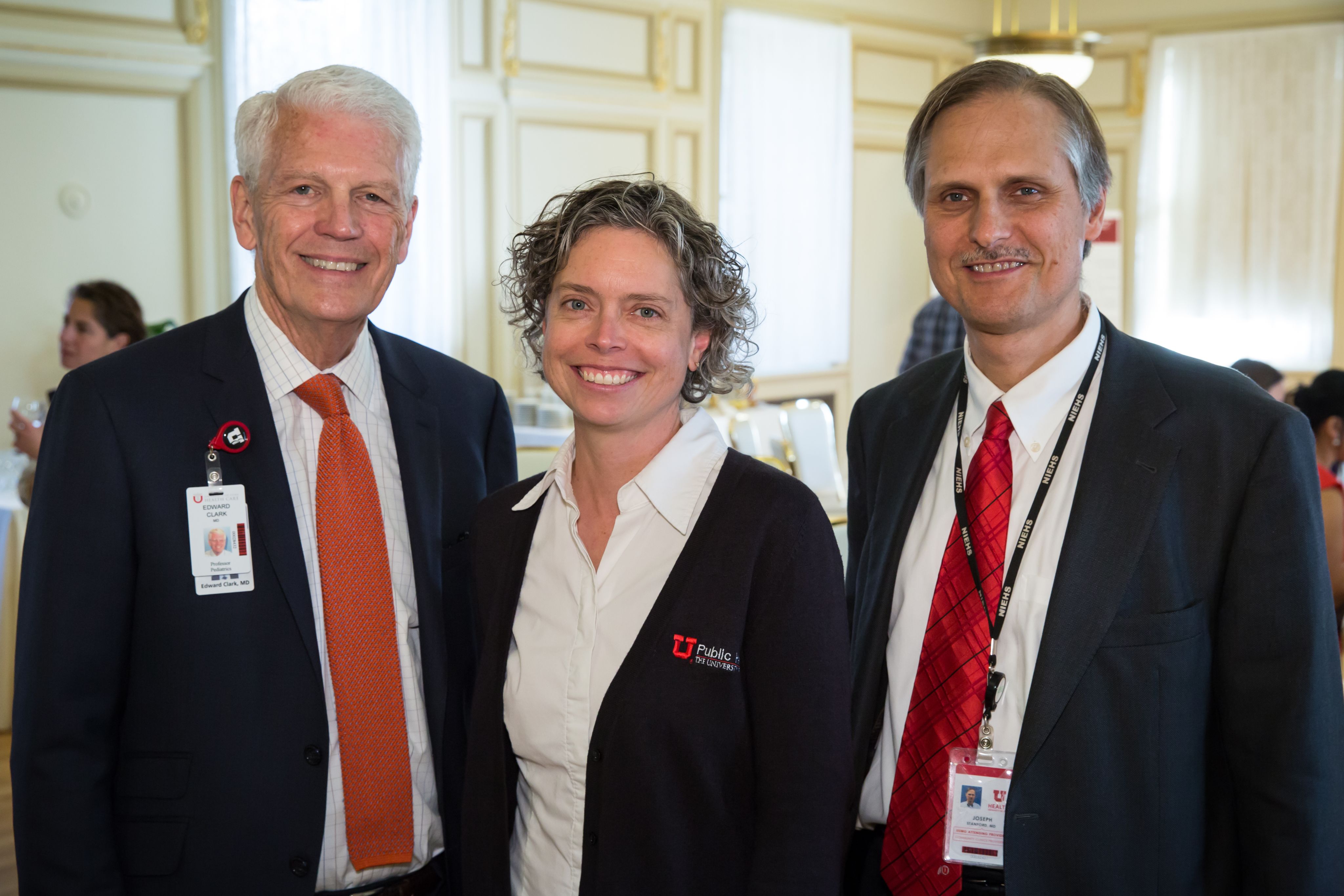

Among pediatricians nationwide, Clark was known for fiercely advocating for a comprehensive study of children’s health. He was the principal investigator on the National Children’s Study, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative in the early 2000s. A broad, wide-ranging study of children’s health over time—100,000 kids for 21 years—it examined the trajectory of their health and was predicated on environmental exposures. The research promised to discover new ways of treating kids and ameliorating the conditions that might get in the way of their health, growth, and development.

That study ended up running into some bureaucratic issues and was eventually decommissioned by the NIH. Nevertheless, Clark cobbled together resources to keep the Utah children’s study going. The Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcome (ECHO) awarded a grant to U of U Health to continue the research as a successor to the National Children’s Study.

Clark celebrating an important milestone of the Utah Children's Project with his co principal investigators Christy Porucznik, PhD, and Joseph Stanford, MD in 2017.

Clark celebrating an important milestone of the Utah Children's Project with his co principal investigators Christy Porucznik, PhD, and Joseph Stanford, MD in 2017.

As a pediatrician and pediatric cardiologist, Clark studied how the embryonic heart develops. Joe Yost, PhD, vice-chair for basic science research in the Department of Pediatrics, knew of Clark and his achievements in cardiology work before he came to Utah. “I first met him when he was a faculty member at the University of Rochester, and he had organized a meeting there that eventually became what’s called the Weinstein Cardiovascular Development meetings,” Yost says.

Dean remembers when Clark first came to Utah as the chair of the Department of Pediatrics, “He had a clinic where he saw adult patients who had congenital heart disease,” Dean says, “and he ran that clinic maybe once every two or three weeks.” The Clark’s Classification of Congenital Heart Disease remains a standard clinical diagnostic tool.

Giardino believes Clark was a true scientific scholar, well-read in several disciplines. “He was an active investigator for many of his years in medicine. He conducted studies. He really did understand what rigor was in scientific work. He could hold his own with the foremost scientists amongst us.”

A MENTOR AND ADVOCATE

First-rate academicians serve as exceptional mentors. Clark took great pride in teaching first-year medical students. He encouraged them to gain humanistic skills alongside technical ones. He was generous with his time and mentored anyone who came to his door looking for guidance. “Ed was highly motivated by the success of people he mentored—students and faculty,” Dean says.

Along with building mechanisms within the pediatrics enterprise to foster research, Yost believes Clark’s mentoring inspired the faculty to become better at research. “He helped them write grants. We put in a large infrastructure that really helped researchers submit grants and get them successfully won.”

Clark was not just an academic physician but, really, a pure academic. He told students and colleagues that, “as we learn the facts, we change our minds.” As Giardino says, “Clark never thought you should stick with something because that’s how we’ve done it before. He was willing to be provocative and say, ‘Maybe that’s not the best way—is there a better way? Let’s study it. Let’s generate the evidence to see if it is actually better, and then do more of that.’”

“Clark never thought you should stick with something because that’s how we’ve done it before. He was willing to be provocative and say, ‘Maybe that’s not the best way—is there a better way? Let’s study it.’”

—Angelo Giardino, MPH, MD, PHD, FAAP; Chair, Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah Health

Clark was consistent in how he thought academic pediatricians or physicians should approach the care of children. For him, academic answers were not always enough. He pushed for policy changes in all sectors of society—and in everyday life—so patients could have the benefit of medical discoveries and treatment innovations. He would challenge research teams to talk to insurance executives, legislators, and regulators, then make a compelling case for getting better medical treatments to all children. “He relished getting all the stakeholders in a room and talking, asking the probing questions, and then really exploring: How could we make this work?” Giardino says. “I thank him for teaching that the academic answer, a new scientific understanding, was not enough.”

A MASTERFUL ADMINISTRATOR

While serving as associate vice president for clinical affairs, Clark also served as president of University of Utah Medical Group (UUMG). For five years, he represented more than 1,600 physicians and others who make up the clinical practices of the academic faculty. Dayle Benson, PhD, executive director of UUMG, says that, from the start, Clark was committed to building trust between the medical group leadership and the health system. “One of his greatest tactics was engaging the audience and getting feedback around issues,” Benson says. “It wasn’t just his agenda but an organizational agenda worthy of vision, creative thinking, intellect, and participation across a complex, non-linear, adaptive health care system. He made sure everyone in the room had a chance to be heard.” Clark established a platform for primary care integration and developed partnerships with other organizations such as the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

“One of his greatest tactics was engaging the audience and getting feedback around issues. He made sure everyone in the room had a chance to be heard.”

Benson points out that Clark was deeply committed to teaching and transparent communications at all levels of the organization. “This made a big difference to connect all of our colleges and the clinical, education, and research missions,” she says. “Ed often referred to the medical group as the workforce planning catalyst for all clinical teams.”

According to Peter Weir, MD, executive medical director of population health, Clark’s extremely careful planning made him an effective administrator. “Ed was always thinking about unintended consequences,” Weir says. “That was one of his phrases that he loved: ‘What are the unintended consequences of doing this? Let’s think this through before we move.’”

A COMMUNITY BEACON

Ed Clark set so many health care initiatives in motion without being seen behind them, says Weir, who Clark recruited to be the medical director of population health. Foremost in Clark’s mind was advancing the health of Utahns. “The big question was, ‘What is our community struggling with?’ Weir says. “And that’s where Ed’s North Star was. Problems like substance abuse and mental health access; epidemics such as diabetes and obesity; health issues like equity and lack of access to care; and ‘frontier’ populations, meaning even more rural than rural. Everything that we did were small little building blocks to build toward a higher vision.”

“The big question was, ‘What is our community struggling with’? And that’s where Ed’s North Star was.”

“Whether people see it or not, so many projects will continue to advance health because of Ed. The Intensive Outpatient Clinic (IOC), which I help lead, fits into that. It’s a building block to advance an important cause—caring for and reaching out to people that have a lot of health needs. It’s a perfect example of better health care that never would’ve happened without Clark. No one even acknowledges it—no one even knows it. And Clark was OK with that. It was egoless altruism.”

The Intensive Outpatient Clinic, pictured here, is just one of the many visionary projects supported by Clark that will continue to transform the health of the community.

The Intensive Outpatient Clinic, pictured here, is just one of the many visionary projects supported by Clark that will continue to transform the health of the community.

Dozens of other programs serve as examples of Clark’s influence and key support. He established the first program in the Mountain West to deliver medical care to transgender children. Lorenzo Botto, MD, professor of pediatrics, says the SOM’s Rare and Undiagnosed Program (the “Penelope Program”) would not be here today—and not be so successful—if not for the vision, will, and unstinting support of Clark. “In 2015, he asked me if I would lead development of a team to address the diagnostic challenges of children with undiagnosed diseases,” Botto remembers. “Clark’s vision was one of team science: a melding of minds—‘cognitive expertise,’ he called it)—depth of experience, and the best technology to solve the most difficult medical mysteries. He understood that doing so would be transformational—and move us towards the ideal trifecta: take better care of children and families, make new scientific discoveries, and instill a team science approach in the next generation of clinician-scientists.”

“From the day I met him in 1998, he never stopped encouraging me and setting bars he knew I could one day clear. He was a believer in people and mentored many of the people I look up to the most. So many people are indebted to him.”

Jennifer Plumb, MD, MPH, pediatric emergency physician, and her brother Sam started a program that provides life-saving Naloxone rescue kits to people throughout the state. The program also provides training on how to administer the medication, which reverses overdoses in just a few minutes by blocking opioid receptors. “Utah Naloxone exists because Dr. Clark believed in me, believed in my brother Sam, and believed in saving lives,” Plumb says. “From the day I met him in 1998, he never stopped encouraging me and setting bars he knew I could one day clear. He was a believer in people and mentored many of the people I look up to the most. So many people are indebted to him. Ed Clark was truly an icon, a culture shifter, and game changer.” Sam agrees: “I hope I can look back on my life with even a fraction of the bright stars in my sky that Ed had in his.”

“For all he did for Utah families, he shied away from the spotlight and turned it towards the team. His legacy—one of a keen intellect, clear vision, and doing what is right, even if it is difficult—is here to stay.”

—Lorenzo Botto, MD, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Utah Health

Clark, who served with the U. S. Coast Guard from 1971 to 1973 as a Marine hospital physician, was passionate about helping veterans. Were it not for Clark’s devout advocacy, the Veterans Affairs Clinic at the South Jordan Health Center would not be serving veterans in a facility more convenient and closer to where they live. When it was dedicated, Clark said, “It’s an ideal fit with part of our mission, which is continually improving individual and community health and quality of life. Vets, obviously, are an important part of our community. And our ambulatory care program is aimed at getting high-quality health care close to patients where they are. The new collaborative clinic also provides us with more opportunities for training and education.”

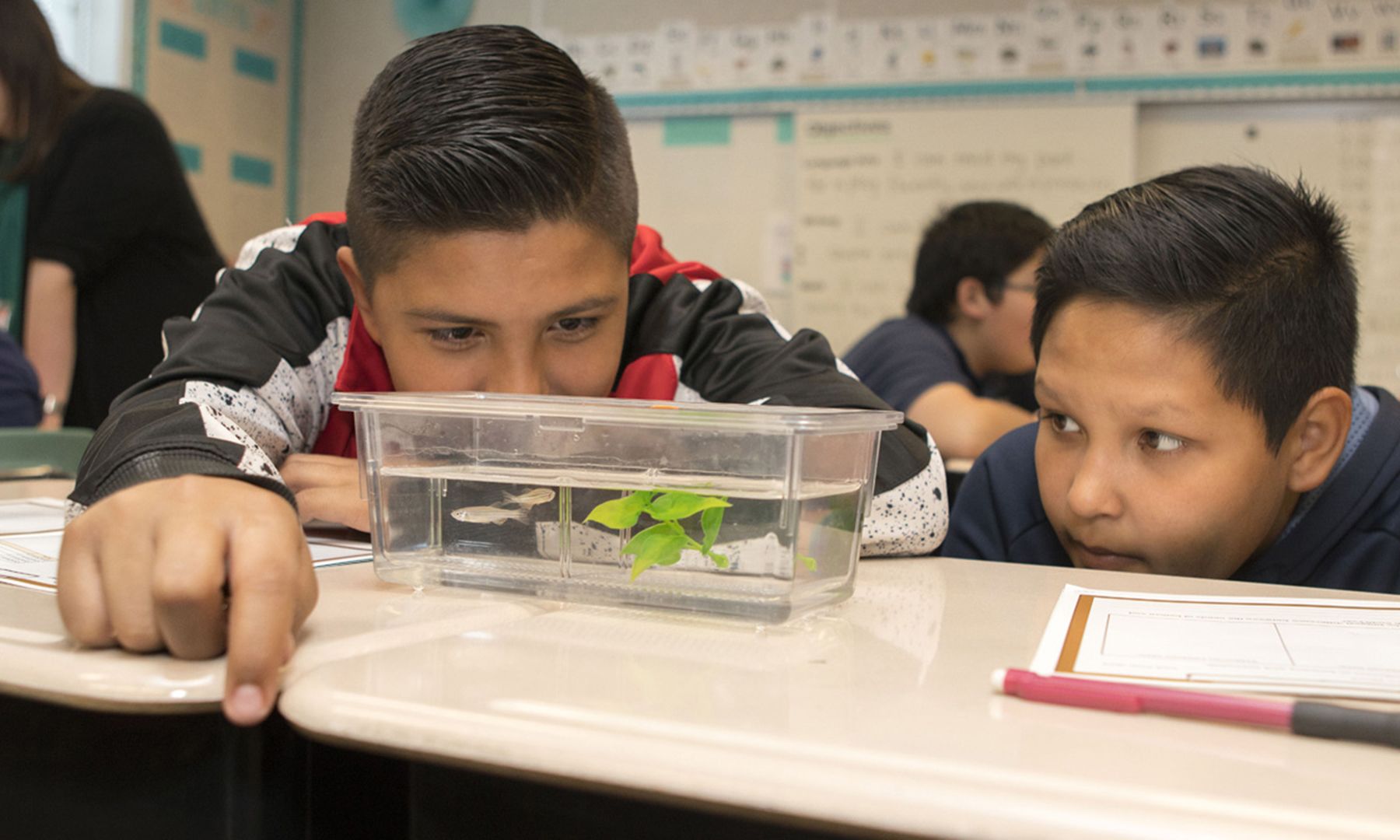

Clark wanted to open the world of science and medicine to all children. Pictured here are children who participated in BioEYES, a hands-on science education program that exposes K-12 students to science, the scientific method, and science exploration.

Clark wanted to open the world of science and medicine to all children. Pictured here are children who participated in BioEYES, a hands-on science education program that exposes K-12 students to science, the scientific method, and science exploration.

Investing in the next generation was also a priority for Clark. With his leadership, U of U Health funded BioEYES, a hands-on science education program that exposes K-12 students to science and the scientific method, while shedding a positive light on science exploration. The Department of Pediatrics-sponsored program reached out to more than 7,000 students during a span of four years. Clark’s goal was to encourage students from underrepresented groups throughout the valley to decide, “Hey, I could be a scientist,” and think about going into medicine or science.

A GOOD PERSON:

CURIOUS, LOYAL, AND KIND

Colleagues all cite something different, though all admirable, when describing Clark’s finest personal qualities—the qualities that allowed him to make lasting contributions to the lives of patients, students, staff members, and faculty for 26 years at the University of Utah.

“I think he was very loyal,” Giardino says. “If he got involved in your career, he felt a responsibility to stick with you through thick and thin and help you develop the career that you wanted to. I think many folks view him as an absolute pivotal mentor who helped them do what they wanted to do in their career.”

“Ed was a good listener, and I think that he listened more than he spoke,” Dean remembers.

Because he was incredibly curious—so forward thinking with such a bright mind—faculty members say his thinking always seemed to be four steps ahead of theirs. Weir remembers meetings in Clark’s office with jazz playing softly in the background. Clark would say, “This is not going to be a meeting where we’re going to talk about the nuts and bolts of issues. We’re going to open up our minds and be expansive.”

Clark had a gift of patience. It allowed him to be generous with his time, not standard practice for academic leaders, scientists, or clinicians. “Every time I’d meet with Ed, first thing he’d say is, ‘Peter, going slow is going fast,’” Weir remembers. “Ed would say, ‘Get it right the first time, slow is fast.’ And I say that to myself every day.”

Weir also points out that Clark believed in the power of humor. “Clark started meetings off with a funny anecdote that would always put people at ease. It was often self-deprecating, or it would be a detached comment about something going well beyond our campus, something in the popular press. It allowed us to all sit back and laugh. It diffused any tension and set the group at ease.”

Other colleagues say Clark was an avid consumer of peanut butter sandwiches and doer of crossword puzzles, sometimes during crowded meetings.

What made Edward Bowersox Clark so great as a doctor, scientist, leader, colleague, and friend? “Ed had an innate kindness,” Benson says. “Kindness in a world that isn’t always so kind. Core to his being was helping people understand that life is tough, but their role in life is meaningful.”

In memoriam of

Edward Bowersox Clark, MD

1944-2022

Written by: William Sorensen

August 11, 2022

Design by: Sandy Kerman, Kerman Design

Contributors: Dayle Benson, Joe Borgenicht, Jane Griffith, Heidi Greenberg, Jesse Colby, Amy Albo, Jessica Cagle, Nick McGregor

Photography courtesy of the Clark Family, University of Utah Health, Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library, Charlie Ehlert, Kristan Jacobsen, Austen Diamond Photography.