Combatting Diabetes by Casting the Net Wide

December 14, 2020

Life with diabetes lends itself to a lonely kind of intimacy. Frequent finger-stick tests to check your blood glucose. Constant adjustments to your insulin intake. Never-ending worries about the fluctuating price of prescription refills that you need to survive.

Multiply that by the 30 million Americans who live with the disease and the picture sharpens. While we create better treatments and search for a cure, we also have to bring resources to disproportionately affected communities and ensure that the 88 million Americans with prediabetes know how to delay or prevent the full-blown disease.

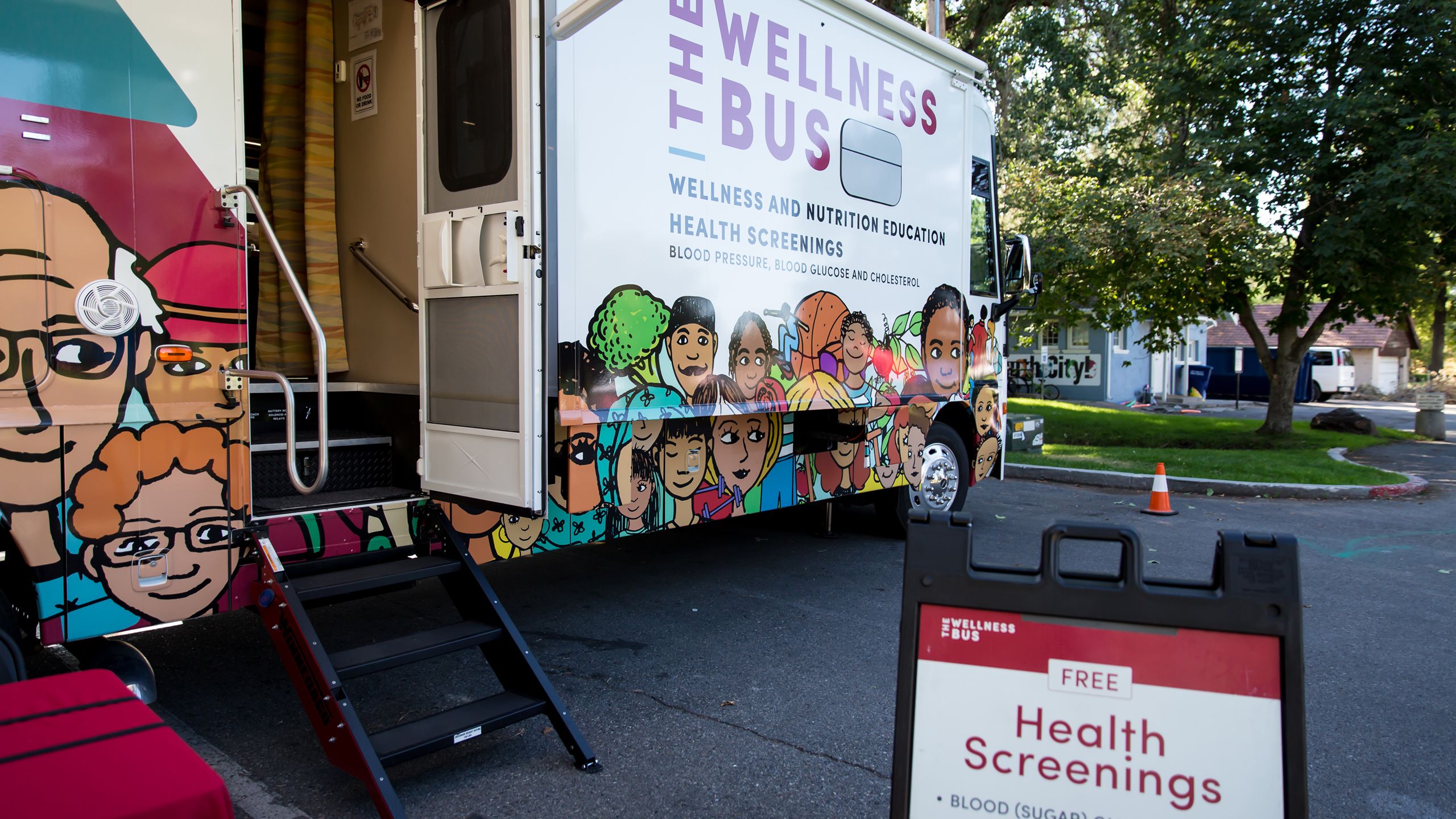

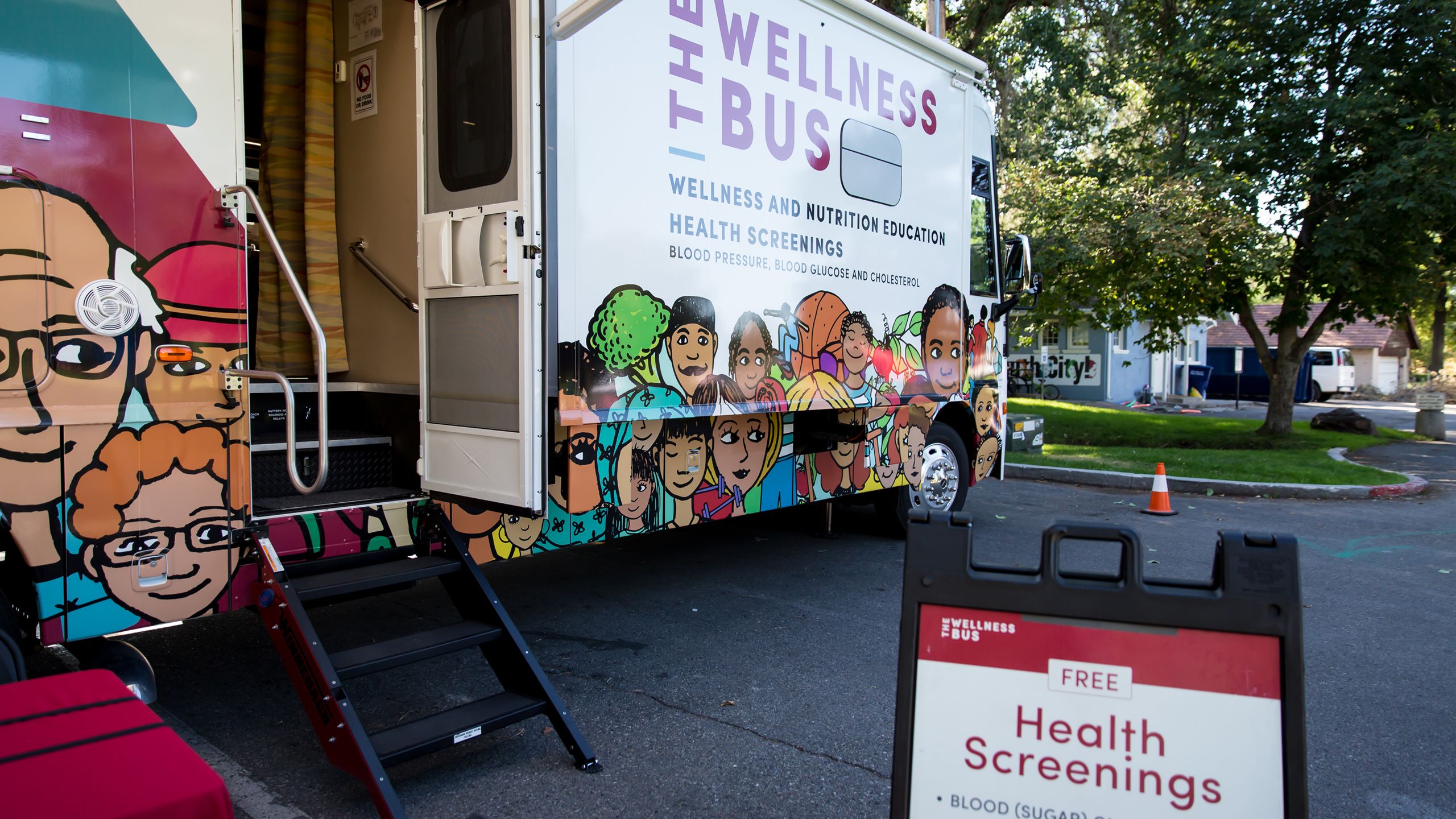

Every time Angelo Restrepo would overeat, he’d feel a sharp pain in his head. Driving to work last July, his headache was so intense that he struggled to focus on the road. Pulling over, the 45-year-old Midvale resident spotted the Wellness Bus—the 40-foot RV that he passes on his way to work. This time, he drove closer and noticed a sign for free blood pressure, blood glucose, and cholesterol screenings. “I decided to get on the bus, hoping to find out why I was feeling so lousy,” Angelo says.

It turns out that Angelo had serendipitously stumbled upon a mobile health clinic with a focused goal: to empower patients struggling with or predisposed to diabetes. Carmen Ramos, MS, RDN, a registered dietitian and health coach at University of Utah Health, greeted Angelo at the door. After testing his blood glucose level, she delivered some life-changing news: it was high enough to trigger a headache and within a range that indicated he was likely living with type 2 diabetes.

She then helped Angelo develop a plan for regular blood glucose testing, nutrition monitoring, and exercise. Urging him to visit his physician for advice on medications that might lower his blood glucose, she also invited him to come back to the Wellness Bus once a month.

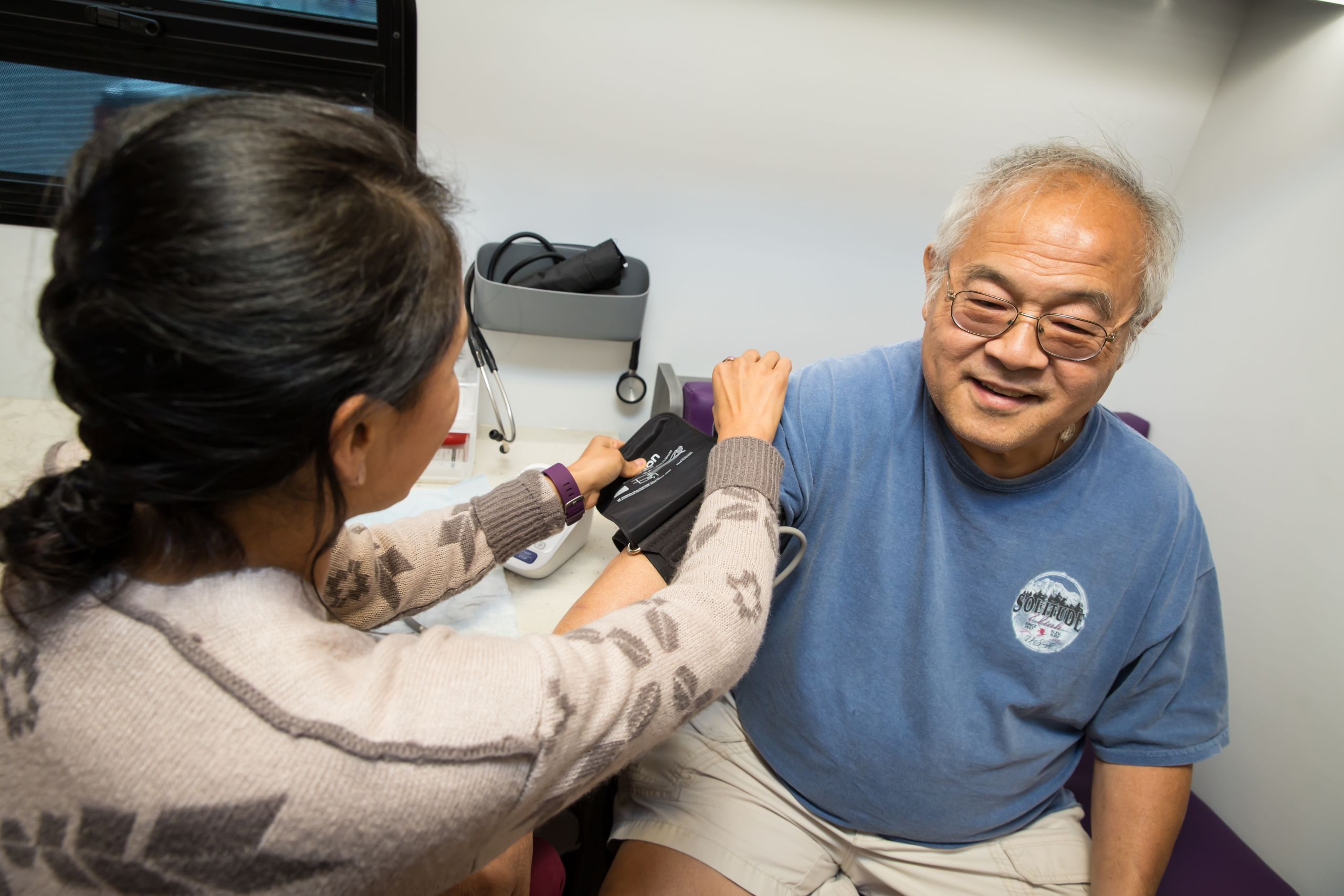

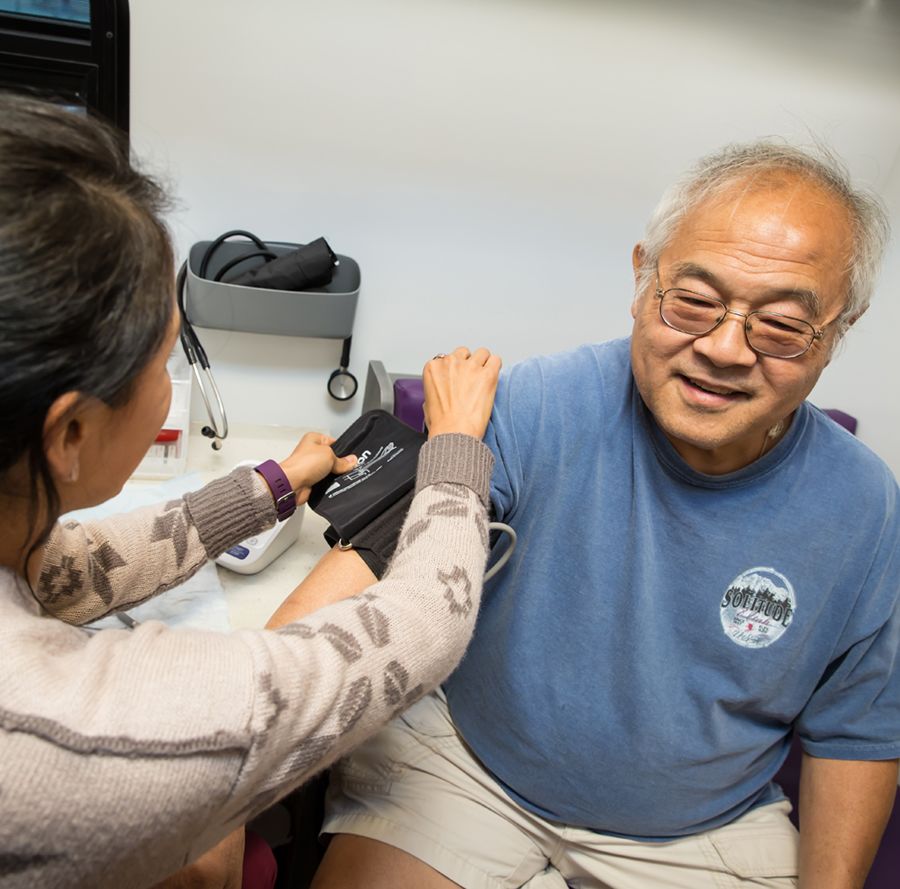

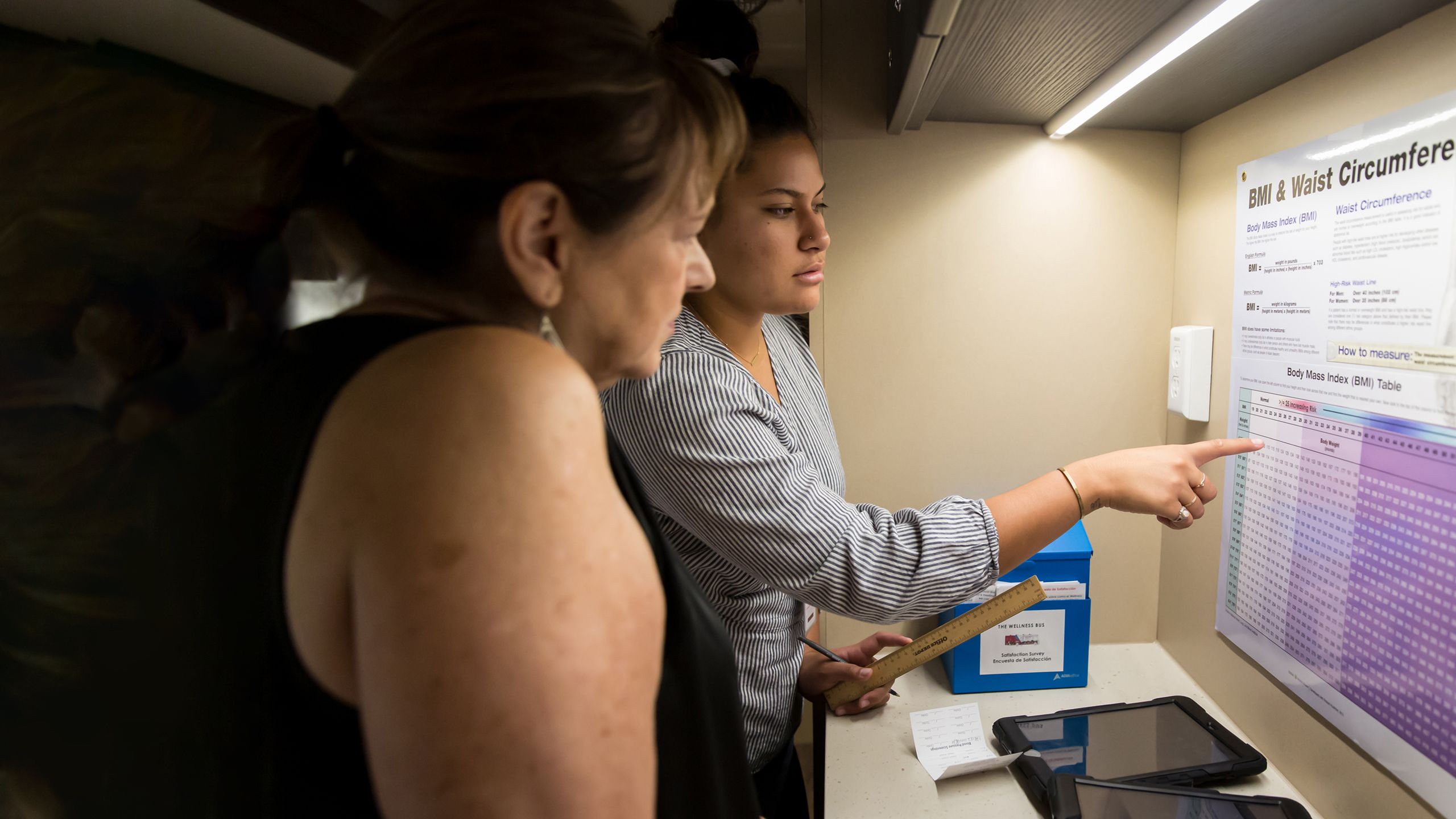

Similar work is done by health coach Monica Salas, MPH (above left), and patient Tom Din (above right), who was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes eight years ago. “If you’re my age and you’re at home most of the time, it’s easy to eat whatever you want and not get off the couch,” says the 68-year-old South Salt Lake resident. “Who’s going to tell me I shouldn’t?” That's changed with the sense of community he found on the Wellness Bus. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Similar work is done by health coach Monica Salas, MPH (above left), and patient Tom Din (above right), who was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes eight years ago. “If you’re my age and you’re at home most of the time, it’s easy to eat whatever you want and not get off the couch,” says the 68-year-old South Salt Lake resident. “Who’s going to tell me I shouldn’t?” That's changed with the sense of community he found on the Wellness Bus. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

The Wellness Bus is part of Driving Out Diabetes, a Larry H. Miller Family Wellness Initiative. Launched in 2017, the $5.3 million project represents collaborative work between the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation and U of U Health. Making the rounds of neighborhoods in South Salt Lake, Midvale, Glendale, and Kearns, the bus provides private, confidential consultations and customized nutrition and exercise plans for patients who don’t have access to the care—and the information—they need. Race, class, and education level all play a role in who the disease affects. Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives are twice as likely to have diabetes as Whites. Those without a high school diploma are twice as likely to have diabetes as those with a college education.

Eliminating these disparities and tackling health inequity is part of Driving Out Diabetes’ goal. Health coaches, screeners, community health workers, registered dietitians, and student volunteers work with patients to treat diabetes—and to help them prevent it from developing in the first place. “Sadly, more than 84 percent of those with prediabetes don’t know they have it,” says Robin L. Marcus, PT, PhD, OCS, professor and former chief wellness officer at U of U Health. Prediabetes is defined as having a higher-than-normal blood glucose level. Without intervention, approximately 70 percent of those individuals will eventually develop diabetes.

“One of the keys in dealing with the diabetes crisis is early diagnosis and education,” Robin L. Marcus says.

“One of the keys in dealing with the diabetes crisis is early diagnosis and education,” Robin L. Marcus says.

Every time Angelo Restrepo would overeat, he’d feel a sharp pain in his head. Driving to work last July, his headache was so intense that he struggled to focus on the road. Pulling over, the 45-year-old Midvale resident spotted the Wellness Bus—the 40-foot RV that he passes on his way to work. This time, he drove closer and noticed a sign for free blood pressure, blood glucose, and cholesterol screenings. “I decided to get on the bus, hoping to find out why I was feeling so lousy,” Angelo says.

It turns out that Angelo had serendipitously stumbled upon a mobile health clinic with a focused goal: to empower patients struggling with or predisposed to diabetes. Carmen Ramos, MS, RDN, a registered dietitian and health coach at University of Utah Health, greeted Angelo at the door. After testing his blood glucose level, she delivered some life-changing news: it was high enough to trigger a headache and within a range that indicated he was likely living with type 2 diabetes.

She then helped Angelo develop a plan for regular blood glucose testing, nutrition monitoring, and exercise. Urging him to visit his physician for advice on medications that might lower his blood glucose, she also invited him to come back to the Wellness Bus once a month.

Similar work is done by health coach Monica Salas, MPH (above left), and patient Tom Din (above right), who was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes eight years ago. “If you’re my age and you’re at home most of the time, it’s easy to eat whatever you want and not get off the couch,” says the 68-year-old South Salt Lake resident. “Who’s going to tell me I shouldn’t?” That's changed with the sense of community he found on the Wellness Bus. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Similar work is done by health coach Monica Salas, MPH (above left), and patient Tom Din (above right), who was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes eight years ago. “If you’re my age and you’re at home most of the time, it’s easy to eat whatever you want and not get off the couch,” says the 68-year-old South Salt Lake resident. “Who’s going to tell me I shouldn’t?” That's changed with the sense of community he found on the Wellness Bus. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

The Wellness Bus is part of Driving Out Diabetes, a Larry H. Miller Family Wellness Initiative. Launched in 2017, the $5.3 million project represents collaborative work between the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation and U of U Health. Making the rounds of neighborhoods in South Salt Lake, Midvale, Glendale, and Kearns, the bus provides private, confidential consultations and customized nutrition and exercise plans for patients who don’t have access to the care—and the information—they need. Race, class, and education level all play a role in who the disease affects. Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives are twice as likely to have diabetes as Whites. Those without a high school diploma are twice as likely to have diabetes as those with a college education.

“One of the keys in dealing with the diabetes crisis is early diagnosis and education,” says Robin L. Marcus, PT, PhD, OCS, former chief wellness officer and professor at U of U Health.

“One of the keys in dealing with the diabetes crisis is early diagnosis and education,” says Robin L. Marcus, PT, PhD, OCS, former chief wellness officer and professor at U of U Health.

Eliminating these disparities and tackling health inequity is part of Driving Out Diabetes’ goal. Health coaches, screeners, community health workers, registered dietitians, and student volunteers work with patients to treat diabetes—and to help them prevent it from developing in the first place. “Sadly, more than 84 percent of those with prediabetes don’t know they have it,” Robin L. Marcus says. “One of the keys in dealing with the diabetes crisis is early diagnosis and education.” Prediabetes is defined as having a higher-than-normal blood glucose level. Without intervention, approximately 70 percent of those individuals will eventually develop diabetes.

PEOPLE WITH DIABETES

WORLD: 422M

1 in 200

U.S.: 30.3M

1 in 11

UTAH: 201K

1 in 20

PEOPLE WITH PREDIABETES

WORLD: 1B

1 in 7

U.S.: 88M

1 in 3

UTAH: 609K

1 in 5

Early interventions can make a major impact on diabetes. That’s the goal of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative and the Wellness Bus. The initiative is generously funded by the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation, with stakeholders like Gail Miller (above). Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Early interventions can make a major impact on diabetes. That’s the goal of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative and the Wellness Bus. The initiative is generously funded by the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation, with stakeholders like Gail Miller (above). Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Ruth Watkins, president of the University of Utah (above, center); Epke Udoh, former Utah Jazz center (upper left); and Gail Miller (center left) promote the Wellness Bus at a community event. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Ruth Watkins, president of the University of Utah (above, center); Epke Udoh, former Utah Jazz center (upper left); and Gail Miller (center left) promote the Wellness Bus at a community event. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

The Wellness Bus delivers mobile education, outreach, and care where it's needed most. That includes communities such as Midvale, South Salt Lake, Kearns, and West Valley City, where residents are predisposed to the disease. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

The Wellness Bus delivers mobile education, outreach, and care where it's needed most. That includes communities such as Midvale, South Salt Lake, Kearns, and West Valley City, where residents are predisposed to the disease. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Patrice Arent, Utah State Representative (above, right) is another community leader working together with the Driving Out Diabetes initiative to improve the lives of residents. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Patrice Arent, Utah State Representative (above, right) is another community leader working together with the Driving Out Diabetes initiative to improve the lives of residents. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

That’s why the Driving Out Diabetes initiative includes nearly 20 programs that empower individuals to understand the impact of diabetes and what they can do to stay healthy. The goal is also to raise awareness about prediabetes so that people can change their habits and those of future generations. Team Thrive programs bring information to high school students who might be more at risk, while one-day intensives give senior citizens the resources they need to manage their diet. Connect2Health student volunteers (see page 62) steer patients to more than 300 community resources, acknowledging that health doesn’t happen in a vacuum. And researchers at U of U Health are figuring out ways to tailor diabetes prevention programs to meet the needs of racially and ethnically diverse populations, along with low-income individuals who are at greater risk.

Many other hurdles remain to reduce the incidence and burden of diabetes. Not least is the skyrocketing price of insulin, which doubled between 2012 and 2016. The national average for a one-month supply currently stands at more than $275, but in March 2020, the Utah Legislature passed a bill capping co-payments for insulin at $30 a month and allowing pharmacists to fill expired prescriptions on an emergency basis. That means families will no longer be forced to choose between putting food on the table or rationing their critical prescription. Still looming is the exponential increase in gestational diabetes among expectant mothers (which has risen in Utah from affecting 1.5 percent of all births in 1997 to 6.2 percent in 2017. Then there’s the overwhelming toll diabetes takes on the health care system, accounting for $237 billion in direct expenditures in 2017—with $90 billion more in lost productivity, chronic unemployment, and premature mortality.

Angela Fagerlin, PhD, director of Driving Out Diabetes, professor at U of U Health and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Angela Fagerlin, PhD, director of Driving Out Diabetes, professor at U of U Health and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

“As our population grows, becoming older and more diverse, reducing the burden of diabetes statewide will become more and more difficult,” Angela Fagerlin, PhD, says. “It’s vital that we develop systems that ensure all patients receive the type of care that Angelo Restrepo has.”

Three months after walking through the doors of the Wellness Bus, Angelo, who had weighed in at 320 pounds, was 27 pounds lighter. His blood pressure had decreased from 160/86 to 118/72, while his A1c number, which provides an average three-month summary of blood glucose level, decreased by a full percentage point thanks to help from his health coach. “If not for Carmen, I wouldn’t have started,” he says. “Stepping on the Wellness Bus was what I needed to move my life in a new direction.”

Early interventions can make a major impact on diabetes. That’s the goal of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative and the Wellness Bus, which delivers mobile education, outreach, and care to communities more predisposed to the disease. The initiative is generously funded by the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation, with stakeholders like Gail Miller (bottom left photo); Ruth Watkins, president of the University of Utah (top photo, center), and Epke Udoh, former Utah Jazz center (upper left); and Patrice Arent, Utah State Representative (bottom right photo, at right) working together with community partners. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

Early interventions can make a major impact on diabetes. That’s the goal of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative and the Wellness Bus, which delivers mobile education, outreach, and care to communities more predisposed to the disease. The initiative is generously funded by the Larry H. & Gail Miller Family Foundation, with stakeholders like Gail Miller (bottom left photo); Ruth Watkins, president of the University of Utah (top photo, center), and Epke Udoh, former Utah Jazz center (upper left); and Patrice Arent, Utah State Representative (bottom right photo, at right) working together with community partners. Photos by Charlie Ehlert

That’s why the Driving Out Diabetes initiative includes nearly 20 programs that empower individuals to understand the impact of diabetes and what they can do to stay healthy. The goal is also to raise awareness about prediabetes so that people can change their habits and those of future generations. Team Thrive programs bring information to high school students who might be more at risk, while one-day intensives give senior citizens the resources they need to manage their diet. Connect2Health student volunteers (see page 62) steer patients to more than 300 community resources, acknowledging that health doesn’t happen in a vacuum. And researchers at U of U Health are figuring out ways to tailor diabetes prevention programs to meet the needs of racially and ethnically diverse populations, along with low-income individuals who are at greater risk.

Many other hurdles remain to reduce the incidence and burden of diabetes. Not least is the skyrocketing price of insulin, which doubled between 2012 and 2016. The national average for a one-month supply currently stands at more than $275, but in March 2020, the Utah Legislature passed a bill capping co-payments for insulin at $30 a month and allowing pharmacists to fill expired prescriptions on an emergency basis. That means families will no longer be forced to choose between putting food on the table or rationing their critical prescription. Still looming is the exponential increase in gestational diabetes among expectant mothers (which has risen in Utah from affecting 1.5 percent of all births in 1997 to 6.2 percent in 2017. Then there’s the overwhelming toll diabetes takes on the health care system, accounting for $237 billion in direct expenditures in 2017—with $90 billion more in lost productivity, chronic unemployment, and premature mortality.

Angela Fagerlin, PhD, director of Driving Out Diabetes, professor at U of U Health, and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Angela Fagerlin, PhD, director of Driving Out Diabetes, professor at U of U Health, and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences. Photo by Charlie Ehlert

“As our population grows, becoming older and more diverse, reducing the burden of diabetes statewide will become more and more difficult,” Angela Fagerlin, PhD, says. “It’s vital that we develop systems that ensure all patients receive the type of care that Angelo Restrepo has.”

Three months after walking through the doors of the Wellness Bus, Angelo, who had weighed in at 320 pounds, was 27 pounds lighter. His blood pressure had decreased from 160/86 to 118/72, while his A1c number, which provides an average three-month summary of blood glucose level, decreased by a full percentage point thanks to help from his health coach. “If not for Carmen, I wouldn’t have started,” he says. “Stepping on the Wellness Bus was what I needed to move my life in a new direction.”

SIGNIFICANT HEALTH DISPARITIES MAKE DIABETES WORSE

Americans with Obesity

4×

more likely to have diabetes than the rest of the population

American Indians/Alaska Natives/Pacific Islanders:

2×

more likely to have diabetes than Whites

Latinx (Hispanics):

1.7×

more likely

Blacks:

1.6×

more likely

THAT’S WHY THE WELLNESS BUS DELIVERS CARE TO THOSE IMPACTED BY SUCH DISPARITIES

Individuals Screened:

3,910

for chronic health conditions

Overweight or Obese:

82%

People of Color:

65%

Latinx (Hispanics):

66%

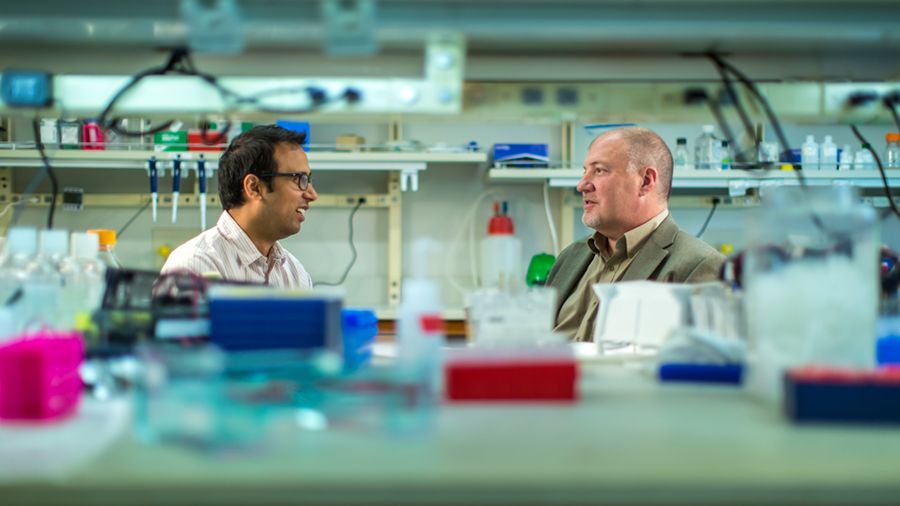

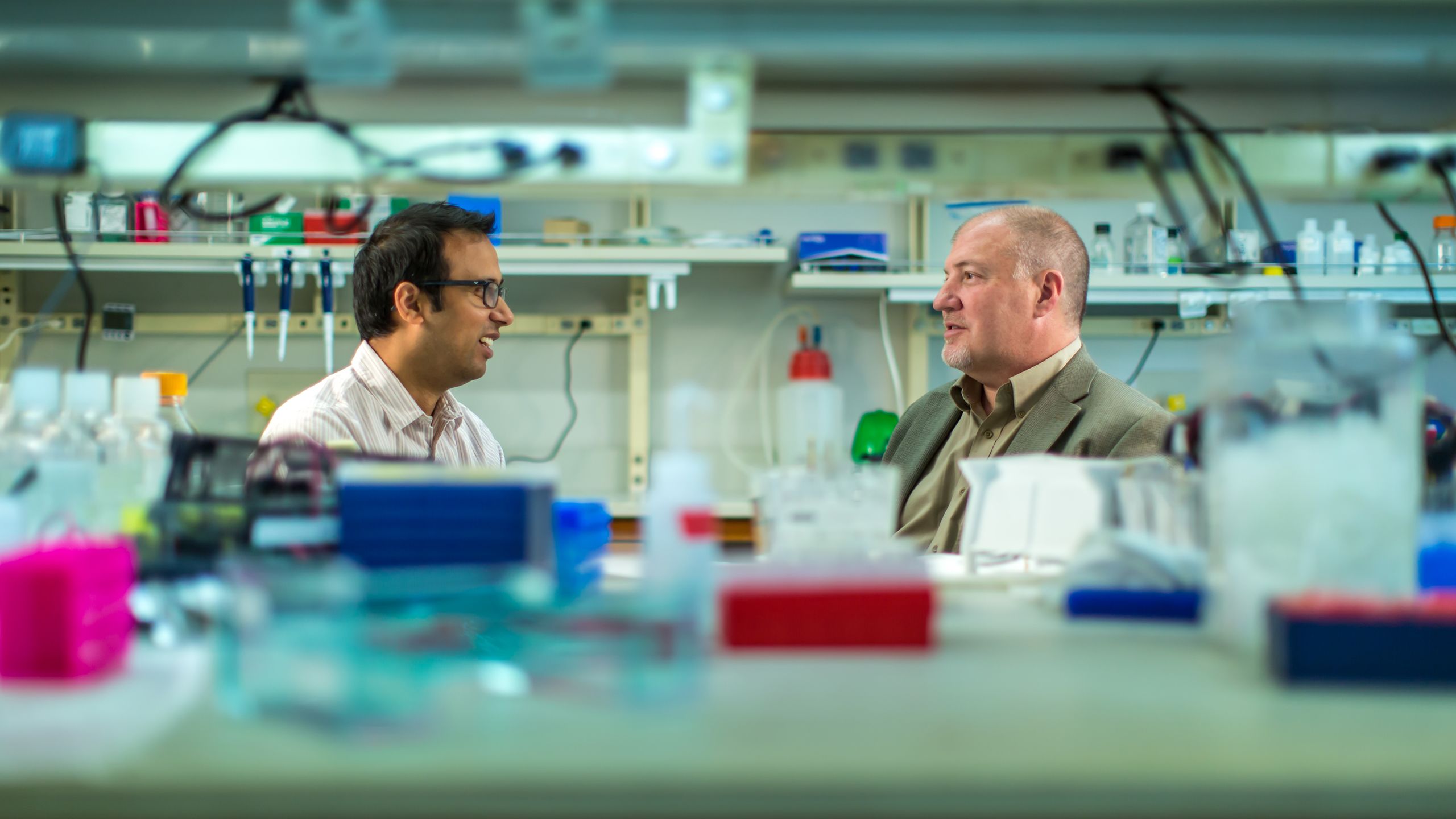

While the Wellness Bus is focused on improving access and education, researchers across U of U Health have an even more ambitious goal: to turn diabetes into yesterday’s memory, not today’s crisis. More than 100 faculty members across 26 departments are investigating the causes of diabetes, new drugs to treat the disease, and the best ways to manage it. Scott Summers, PhD (right), co-director of the Diabetes and Metabolism Research Center, leads the brilliant minds working on these questions. But the reality is that they are difficult to answer.

No one understands that better than Summers. When he was 14 years old, his father, an avid runner and fit 41-year-old, was unexpectedly diagnosed with diabetes. Shortly after, young Scott made his father, Jerry, a bold promise: He would find a cure. However, 34 years later, Jerry, now almost 80 years old, told his son that “time was running out.” Scott admits he probably won’t cure diabetes in his father’s lifetime. “The body is much more complicated than we realize, and our understanding is still juvenile,” he says.

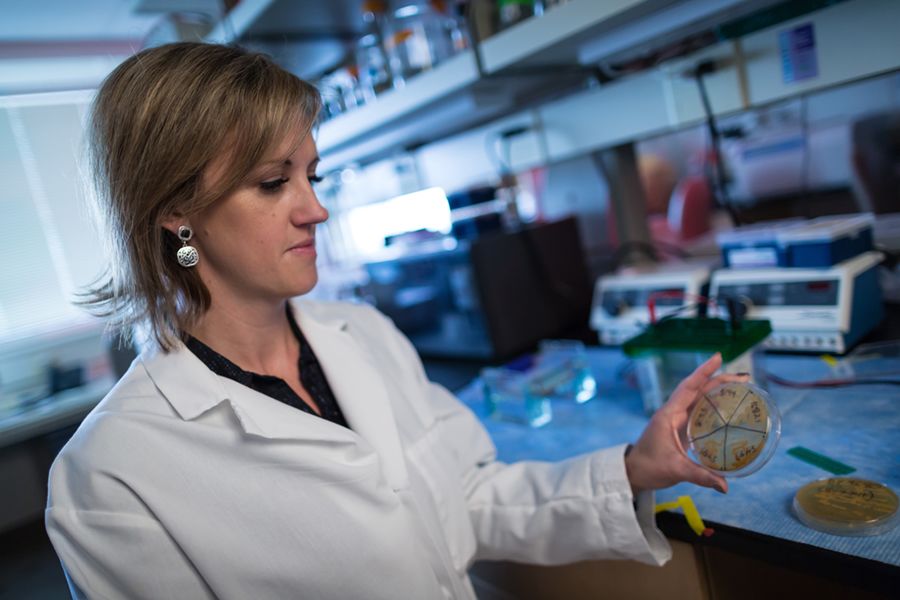

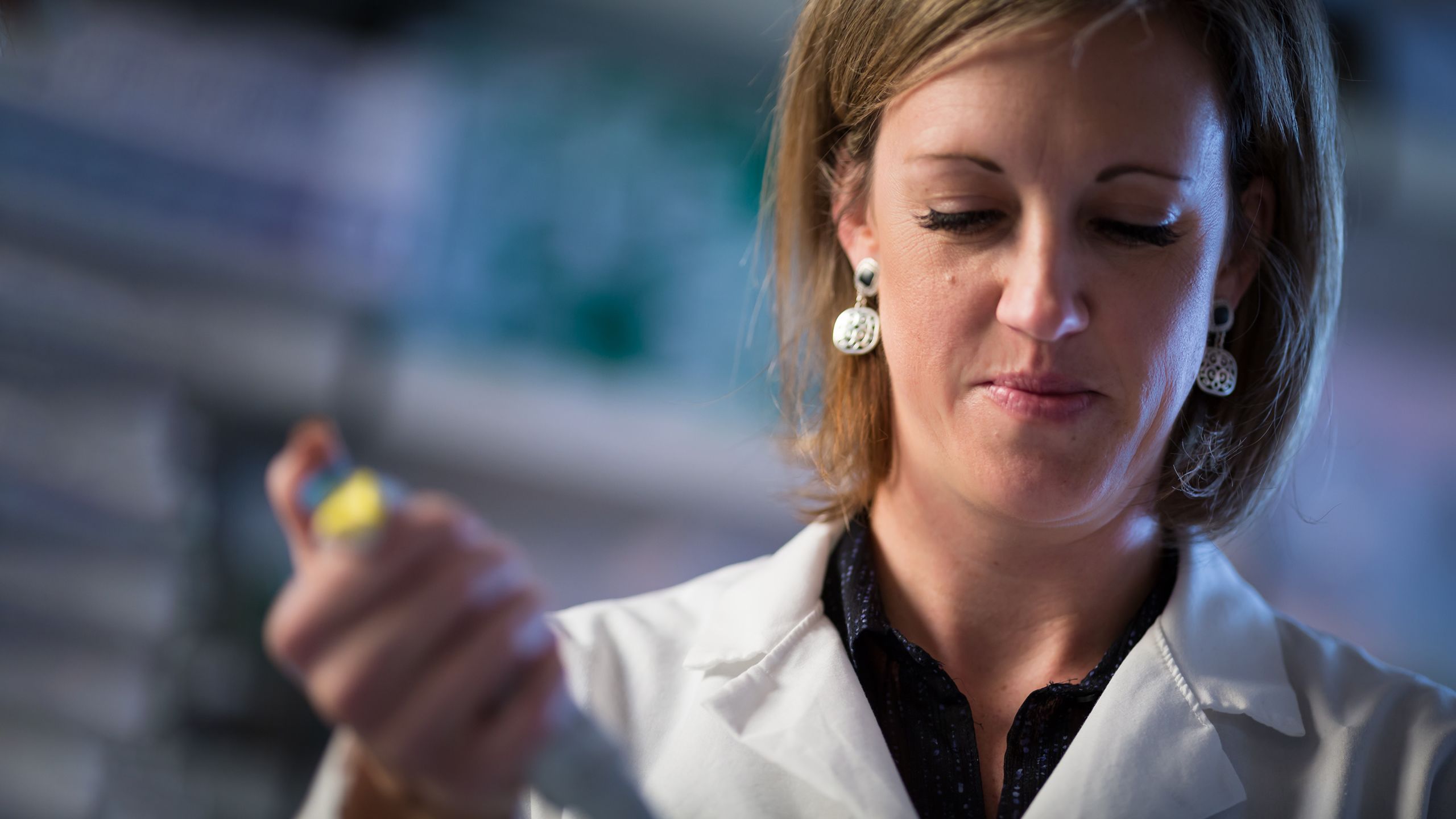

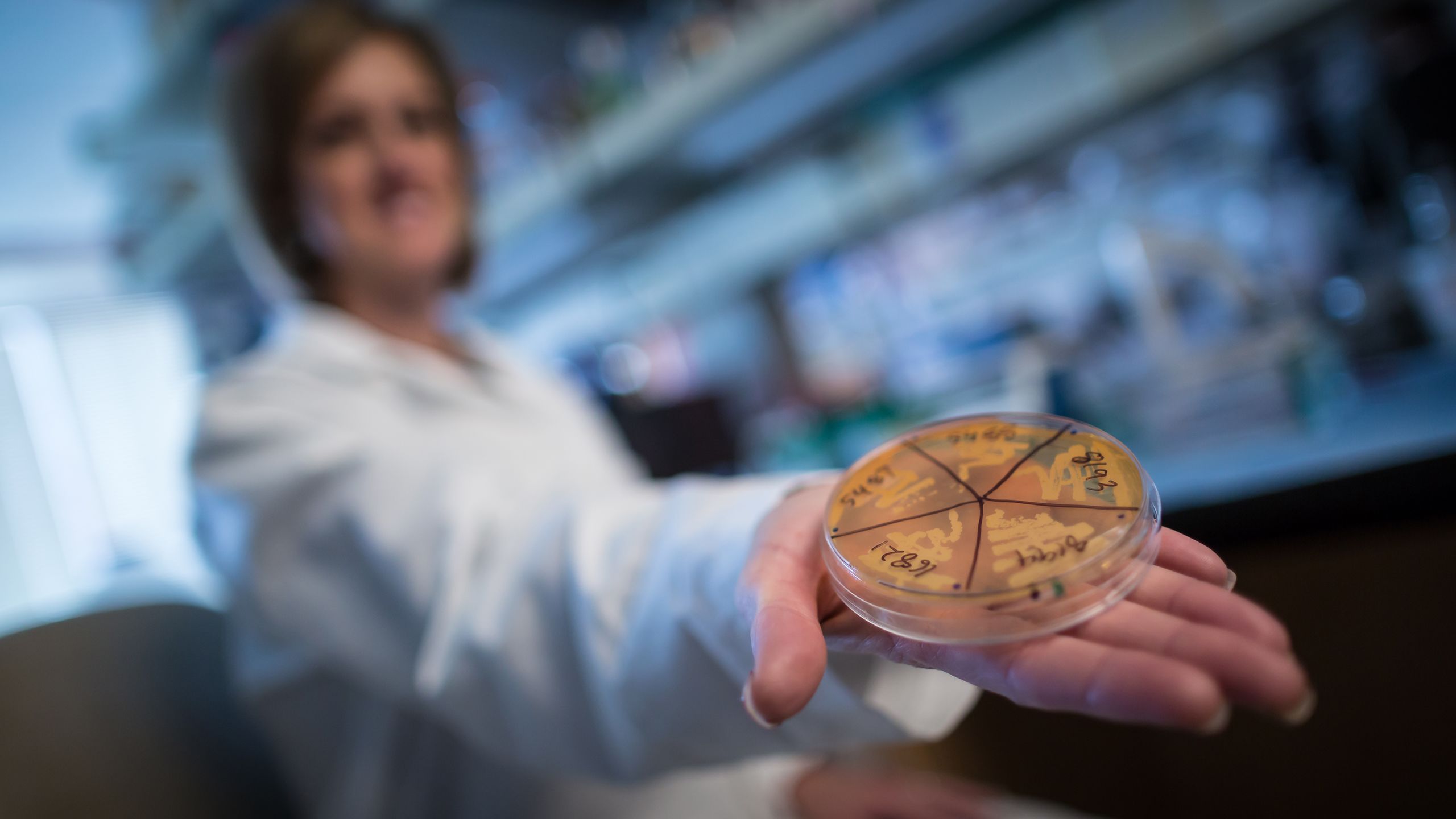

The complexity notwithstanding, exciting progress is being made. Researchers like June Round, PhD (right, holding research module); William Holland, PhD; and Michelle Litchman, PhD, FNP-BC, FAANP, are working on innovative studies linking gut bacteria, regenerated insulin-producing cells, and social determinants of health to diabetes care. Scientists like Marcus Pezzolesi, PhD, MPH (right), are also tapping into the Utah Population Database to track genetic drivers of diabetes. And clinicians are discovering new ways to deliver information so that patients and providers can collaborate more effectively on disease management.

That diversity of work underpins the holistic mission of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative, translating the knowledge discovered in research labs into transformative care delivered in clinics and education shared with the community.

June Round, PhD, an associate professor of pathology at U of U Health, has identified a specific class of gut bacteria that prevents mice from becoming obese. “We’ve stumbled onto a relatively unexplored aspect of type 2 diabetes and obesity,” Round says. “This work will open new investigations on how the immune response regulates the microbiome and metabolic disease.” Photo by Charlie Ehlert

June Round, PhD, an associate professor of pathology at U of U Health, has identified a specific class of gut bacteria that prevents mice from becoming obese. “We’ve stumbled onto a relatively unexplored aspect of type 2 diabetes and obesity,” Round says. “This work will open new investigations on how the immune response regulates the microbiome and metabolic disease.” Photo by Charlie Ehlert

While the Wellness Bus is focused on improving access and education, researchers across U of U Health have an even more ambitious goal: to turn diabetes into yesterday’s memory, not today’s crisis. More than 100 faculty members across 26 departments are investigating the causes of diabetes, new drugs to treat the disease, and the best ways to manage it. Scott Summers, PhD (below, right), co-director of the Diabetes and Metabolism Research Center, leads the brilliant minds working on these questions. But the reality is that they are difficult to answer.

Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Photo by Charlie Ehlert

No one understands that better than Summers. When he was 14 years old, his father, an avid runner and fit 41-year-old, was unexpectedly diagnosed with diabetes. Shortly after, young Scott made his father, Jerry, a bold promise: He would find a cure. However, 34 years later, Jerry, now almost 80 years old, told his son that “time was running out.” Scott admits he probably won’t cure diabetes in his father’s lifetime. “The body is much more complicated than we realize, and our understanding is still juvenile,” he says.

The complexity notwithstanding, exciting progress is being made. Researchers like June Round, PhD; William Holland, PhD; and Michelle Litchman, PhD, FNP-BC, FAANP, are working on innovative studies linking gut bacteria, regenerated insulin-producing cells, and social determinants of health to diabetes care. Scientists like Marcus Pezzolesi, PhD, MPH (below), are also tapping into the Utah Population Database to track genetic drivers of diabetes. And clinicians are discovering new ways to deliver information so that patients and providers can collaborate more effectively on disease management.

Photo by Charlie Ehlert

Photo by Charlie Ehlert

That diversity of work underpins the holistic mission of the Driving Out Diabetes initiative, translating the knowledge discovered in research labs into transformative care delivered in clinics and education shared with the community.

IN 2018–19 ALONE

More than

100

clinicians, researchers, and educators

Across

26

departments

And

8

colleges

Have raised

$65M

in funding

Publishing more than

100

peer-reviewed articles

All with

1

goal in mind:

Turning diabetes into a thing of the past

Since April 2020, the Wellness Bus has been redeployed to conduct COVID-19 testing in many of the same under-resourced neighborhoods where diabetes care is so important.

Two-thirds of the individuals tested so far identify as Latinx (Hispanic). Information about the Wellness Bus’ shift to COVID-19 testing has been promoted by 15 community partners, including the Urban Indian Center, the Mexican Consulate, the Utah Pacific Islander Health Coalition, and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

“Combatting Diabetes by Casting the Net Wide”

Words by Nick McGregor with Bill Sorensen

Design by

Jesse Colby

Extra thanks to

Julie Kiefer, Jen Pilgreen, Sarah Schlaefke, Bridget Hughes, and Sara Salmon