UPON A SOLID FOUNDATION

The year is 1905 and the University of Utah’s first medical program opens with 14 students in a small classroom in the LeRoy Cowles Building. Led by Stanford and Cornell transplant, Ralph Chamberlain, Ph.D., the program begins with six professors and a budget of $10,000.

Chamberlain couldn't have known it, but the early 1900s would prove a tumultuous time to try to start and grow a new academic program. 1917 saw the United States drawn into World War I, which stunted the U of U medical program for a time. Soon after the war, the Great Depression hammered the country, making it difficult for students to pay their tuition and for the university to pay its professors. Conflict would again shake the program as World War II broke out in the Europe, further diverting attention, resources, and people away from academia.

The small U of U medical program was buffeted and tossed through these remarkable world events, but it survived and, in time, grew. Eventually, the program expanded beyond the capacity of the University of Utah campus and by the 1950s U of U medical students were calling the old Salt Lake County General Hospital home.

The hospital, by all accounts, left much to be desired.

“I recall one time doing a common bile duct operation and the light went out,” recounts Wallace Brooke, M.D., Ph.D., in The Gift of Health Goes On. “I called for the circulating nurse to ‘go get Chris,’ who was the only electrician who knew the old circuits. Then came the horrible realization that Chris was the man upon whom I was operating. We finished the surgery with flashlights.”

So, the need for a change was clear. By 1956, medical school leadership had obtained $10 million from the University of Utah Board of Regents to build a new medical center on campus. $15 million followed from the State of Utah and another $4 million from private donors filled the coffers for the creation of the center, which would include a new School of Medicine and attached hospital.

Phillip Price, M.D., dean of the U of U School of Medicine, said that the new facility "would not be palatial or fancy, but which would facilitate carrying on the highest grade of scientific work, which by the quality and reputation of its clinical work would attract patients from the whole mountain region irrespective of their economic status, and which would have such a standing in the community that the best physicians and surgeons of the city would aspire to its visiting staff."

Construction ensued and in 1965 the long-awaited day came. The new University Medical Center, also known as the School of Medicine and Building 521, was completed and welcomed in nearly 500 faculty and 300 students.

True to Price’s words, the School of Medicine offered a destination for those seeking the best care, as well as a launching pad for discoveries, innovations, and breakthroughs that would change the state, the country, and the world.

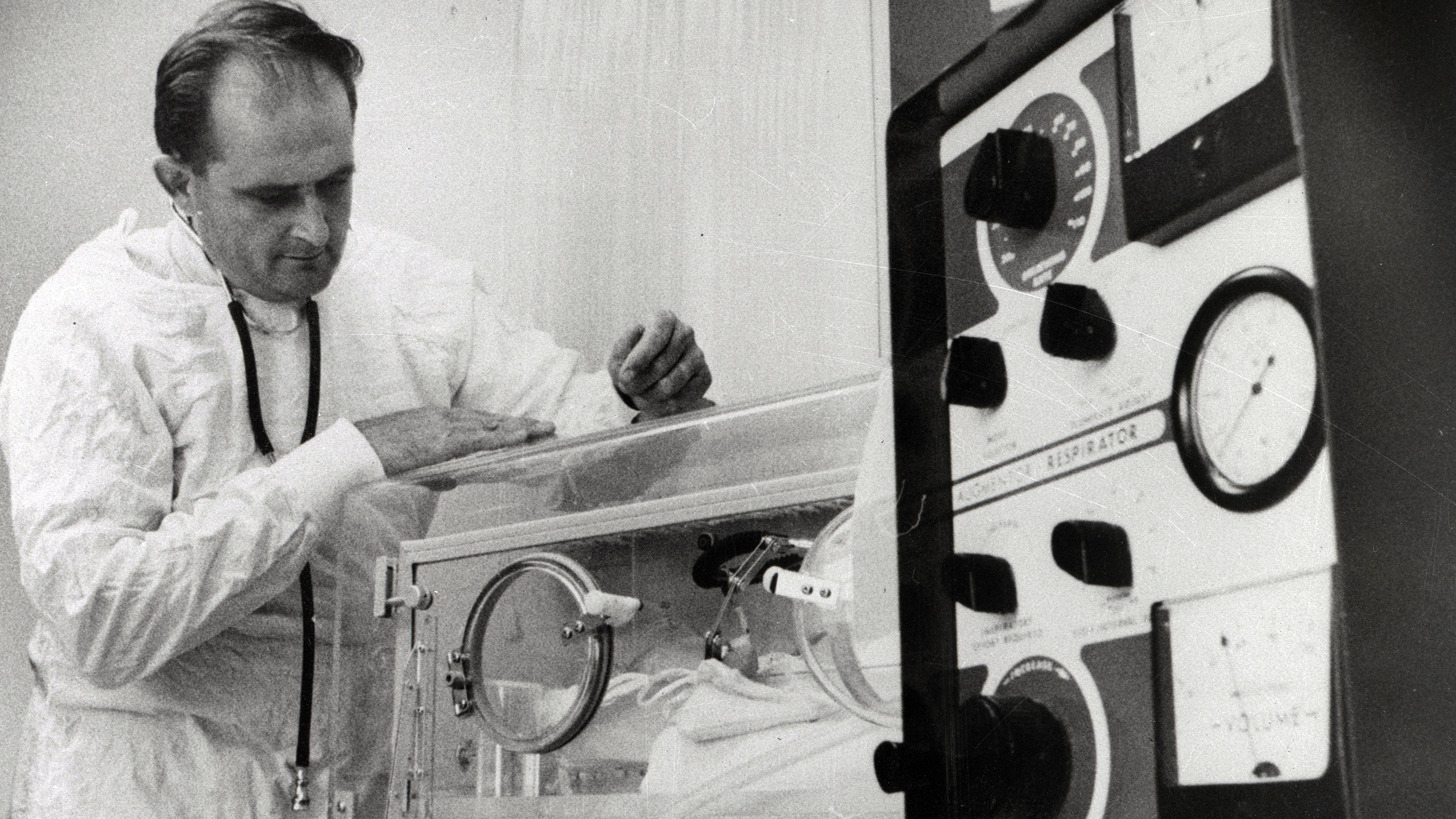

Among the innovations was the creation of the first neonatal intensive care unit in the Mountain West in 1968. Led by August Jung, M.D., University of Utah’s NICU was the first of its kind between Denver and the West Coast. As funding was in short supply, hospital administrators begged and borrowed equipment from wherever they could find it. There was even a bake sale conducted to help purchase a heart monitor.

The best equipment, though, doesn’t guarantee quality outcomes for patients: the best people do. Thanks to the work of Jung and his staff, the infant mortality rate within the NICU’s service area was halved in one year.

In December 1982, all eyes were on the University of Utah as William DeVries, M.D. prepared to attempt the first successful permanent total artificial heart implant surgery on a human. The procedure had been attempted twice previously in Texas, but unfortunately both patients had passed way without ever regaining consciousness. Now it was Barney Clark, D.D.S., a dentist from Seattle with congestive heart failure, who would next go under the knife.

For the seven hours the operation lasted, the world waited to hear of Clark’s condition. Success would be achieved if Clark survived the surgery and regained consciousness, which he did. In fact, Clark, whose life expectancy before the surgery had been measured in days, lived for an additional few months before an infection eventually took his life. Though natural hearts remain the best option for transplants, since DeVries and Clark’s monumental day in 1982, thousands of patients have been kept alive by an artificial heart while awaiting a natural heart transplant.

As the calendar moved toward the turning of a new century, the accomplishments and milestones would continue for what is today know as University of Utah Health. Bolstered by a reputation for the highest quality education, innovation, and care, U of U Health would grow at an increasingly rapid pace. From a 14-student, two-year medical program was born a health system that today prepares 1,250 healthcare providers and welcomes over two million patients in its dozens of statewide health centers and hospitals every year.

The School of Medicine has served the patients, faculty, staff, and students of University of Utah Health well, but after more than five decades the time has come to replace the aging building. Replacing the building, coupled with the extraordinary growth that U of U Health is experiencing, called for big ideas and a lot of work. It called for U of U Health to be transformed.

At its heart, the School of Medicine is just that: a school. Before the School of Medicine comes down, the Medical Education & Discovery building will be built as the new home for medical students, faculty, and staff for years to come.

The building will be the flagship facility for medical education and innovation. This landmark building will modernize medical education and training efforts across the health sciences. Once completed, U of U Health will have a building that equals the high quality of its teaching and research faculty. Students will have a leading-edge place to learn, inquire, and train to become the healthcare leaders of tomorrow. The building will not only continue the tradition of excellence that has become the hallmark of University of Utah Health, but allow those who work and study within its walls to reach farther than has ever been possible before, thus continuing the tradition of excellence that has become the hallmark of University of Utah Health.

The opportunities the new building will create has drawn the attention of leading individuals and organizations across the state. For example, the Medical Education & Discovery building will include a specialized innovation and discovery center named for the late James Levoy Sorenson, the renowned entrepreneur and philanthropist.

Mr. Sorenson was a prolific inventor and helped create a number of groundbreaking medical devices, including the disposable surgical mask and the first real-time computerized heart monitoring systems. As a part of the building, his legacy, the James Levoy Sorenson Innovation and Discovery Center, will offer faculty and students spaces designed to imagine and bring to life the next generation of medical breakthroughs, thus continuing the legacy of innovation and invention that has stood as a hallmark of University of Utah Health.

When U of U Health leadership began to investigate how to best replace the old School of Medicine building, it became clear that the new Medical Education & Discovery building alone would not adequately support the many missions and functions of that venerable facility.

In order to continue to best serve University of Utah Health patients several major new facilities would be required, particularly for the clinical pieces that once called the School of Medicine home.

To help support U of U Health’s growth and create a home for the faculty and staff of the old School of Medicine, a new office building will be constructed on Mario Capecchi Drive. Dubbed the Healthcare, Educators, Leaders & Innovators Complex (HELIX), the building will be connected to campus by a sky bridge. This new office building will give U of U Health faculty and staff a place to work to create better outcomes for patients.

University of Utah Health’s Campus Transformation is an enormous undertaking. When completed, it will provide new ways of working with needed space for more collaboration and improved efficiencies of care and education focused on patients, students, and faculty. The facility changes will positively transform our culture and identity.

These leading-edge facilities will enable talented faculty and students to revolutionize advances and promote discovery in health care. Within the transformed campus, solutions to the 21st century’s greatest medical and patient-care challenges will be found in the convergence of fundamental research, innovative education, and cutting-edge patient care. The campus will become a living laboratory that will bring together some of the world’s brightest minds where they will change the way medicine and science are taught, practiced, and delivered.