Spinal Muscular Atrophy was the top genetic killer of infants. Parents went from the joy of a newborn baby to losing their toddler before they were three years old.

But in December 2016, gene therapy stopped SMA in its tracks. Infants who received those revolutionary treatments now live life to the fullest at home, at school and at play.

With the advent of gene therapy, the future of untreatable genetic diseases will never be the same.

Whit Coleman married his high school sweetheart, Lindsey Mathie, in their early 20s. In late 2007, the Salt Lake City-based couple had a son, Jonas. A week after his birth, Whit, a pediatric nurse, noticed Jonas wasn’t reaching developmental milestones.

Their pediatrician ordered Jonas a swallow test, which revealed an alarming lack of muscle control that was impacting his ability to keep his airway clear of food. A feeding tube was inserted into and down his nose to his stomach.

There were two initial diagnoses: either infantile botulism, which Whit knew was curable, or a neuromuscular condition he knew nothing about called Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

They went to see Kathy Swoboda, MD, a specialist in inherited neuromuscular diseases and movement disorders at University of Utah Health and Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital. As they waited, another staff member advised them not to Google SMA. That was the first thing they did. What they learned was terrifying:

Infants with SMA rarely made it past three years old, dying from paralysis as their muscles wasted away. It was the leading genetic cause of infant death in the country.

Swoboda confirmed Jonas had SMA. Both parents were carriers of the gene that caused SMA, which meant they had a one in four chance of having a baby with the fatal disease.

Lindsey was distraught. “Bad things never happen in my world,” she thought.

Through that long night as Jonas slept, she cried on Whit’s shoulder, repeating again and again, “It can’t be. This can’t be. It just can’t be.”

By the time Jonas was one year old, he couldn’t sit up on his own, play by himself, or control his head movements.

He communicated by blinking once for yes, twice for no. Breathing exhausted him, and the Colemans always had a BiPAP breathing machine on hand to ensure he had adequate oxygen.

Whit and Lindsey were both struck by how Jonas seemed to have a maturity beyond his years. They felt sometimes as if he were trying to help them cope with his plight.

They took him to Disneyland in a specially modified van, and also to Lake Powell with his cousins so he could experience the lake’s waters, the sun on his skin, and, for a few weeks at least, the pleasures of childhood. As Jonas’ third birthday approached, he changed.

“I can see the light fading from his eyes,” Lindsey told Whit.

Jonas caught a cold and needed antibiotics and intubation to survive, but his parents felt he had had enough. They believed he wanted them to let him go.

After excruciating days and nights of struggling to decide the right thing to do, Whit and Lindsey reached a decision. They took off his BiPAP support and, within moments, their two-year-old was gone.

Brave new world

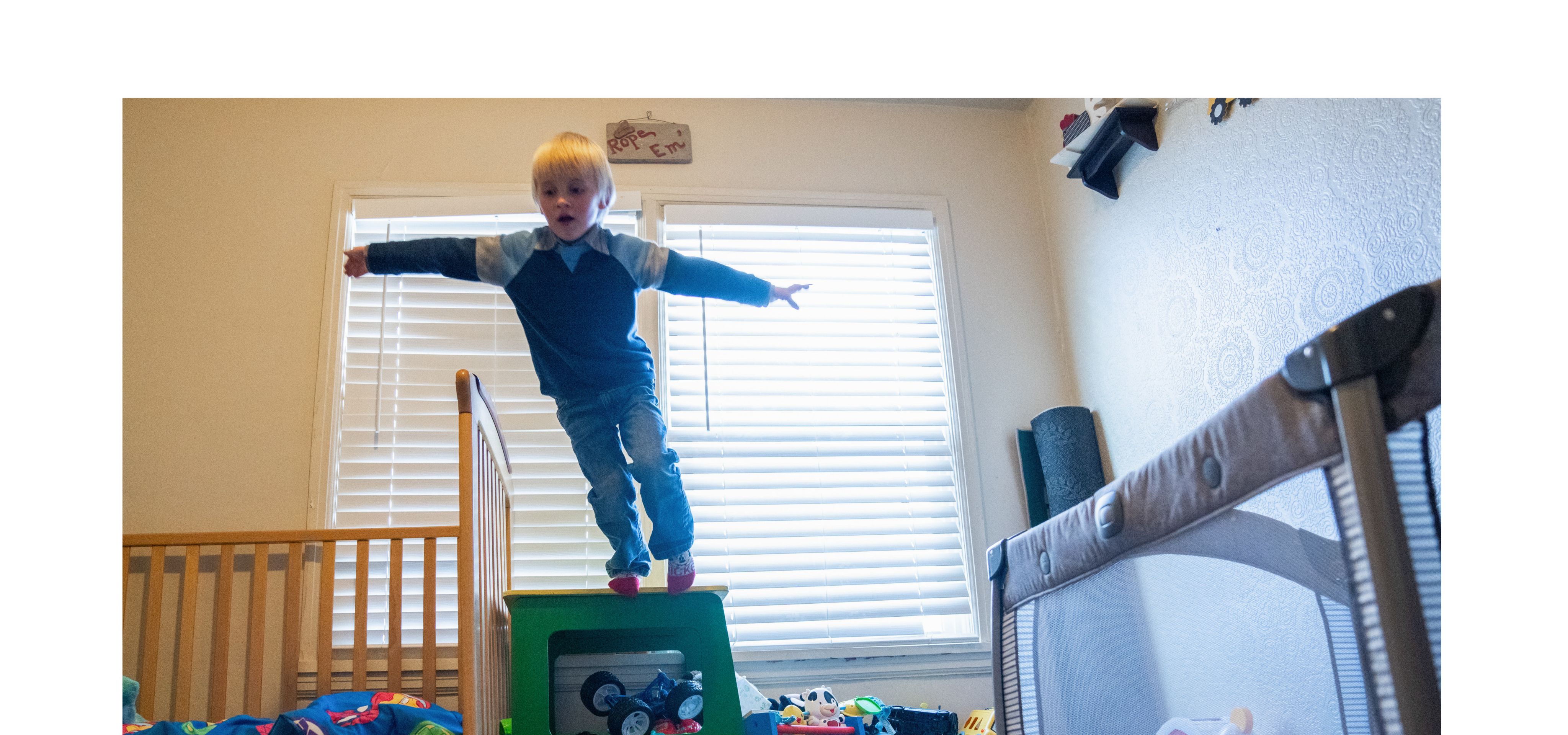

Fifteen years after Jonas Coleman’s death, a five-year-old boy ran up to an enormous window and gazed into a world of sharks and tortoises lazily swimming by. He was born with SMA, received a new type of treatment days after his birth, and has never displayed a single symptom. Children like him, who have received gene therapy for SMA, are beneficiaries of a revolution driven by a union of science, research, and medicine.

The boy was at a local aquarium where an annual family celebration was being thrown by the Utah Program for Inherited Neuromuscular Disorders (UPIN). UPIN works with families to research and treat inherited nerve or muscle disorders.

The program’s director, Russ Butterfield, MD, PhD, a specialist at U of U Health and Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital, put up a series of slides that cited recent U.S. Food & Drug Administration approval of treatments for genetic diseases.

“When I used to do these slides, the treatments were so far away,” Butterfield told the room. “Now we can’t keep up with them.”

Among the newly approved gene therapies was Elevidys for four- and five-year-old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD); a new genetic therapy for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS); a new treatment for the spinal cord nerve degenerative disease Friedreich’s ataxia; and a new steroid treatment for DMD approved that very week. As many as 60 new gene and cell therapies were expected to debut by 2030.

Butterfield compared the escalation in new treatments to the rollout of antibiotics 100 years ago. One day there was nothing, the next a life-saving drug that vanquished bacterial infection. Gene therapy is the same kind of game-changer.

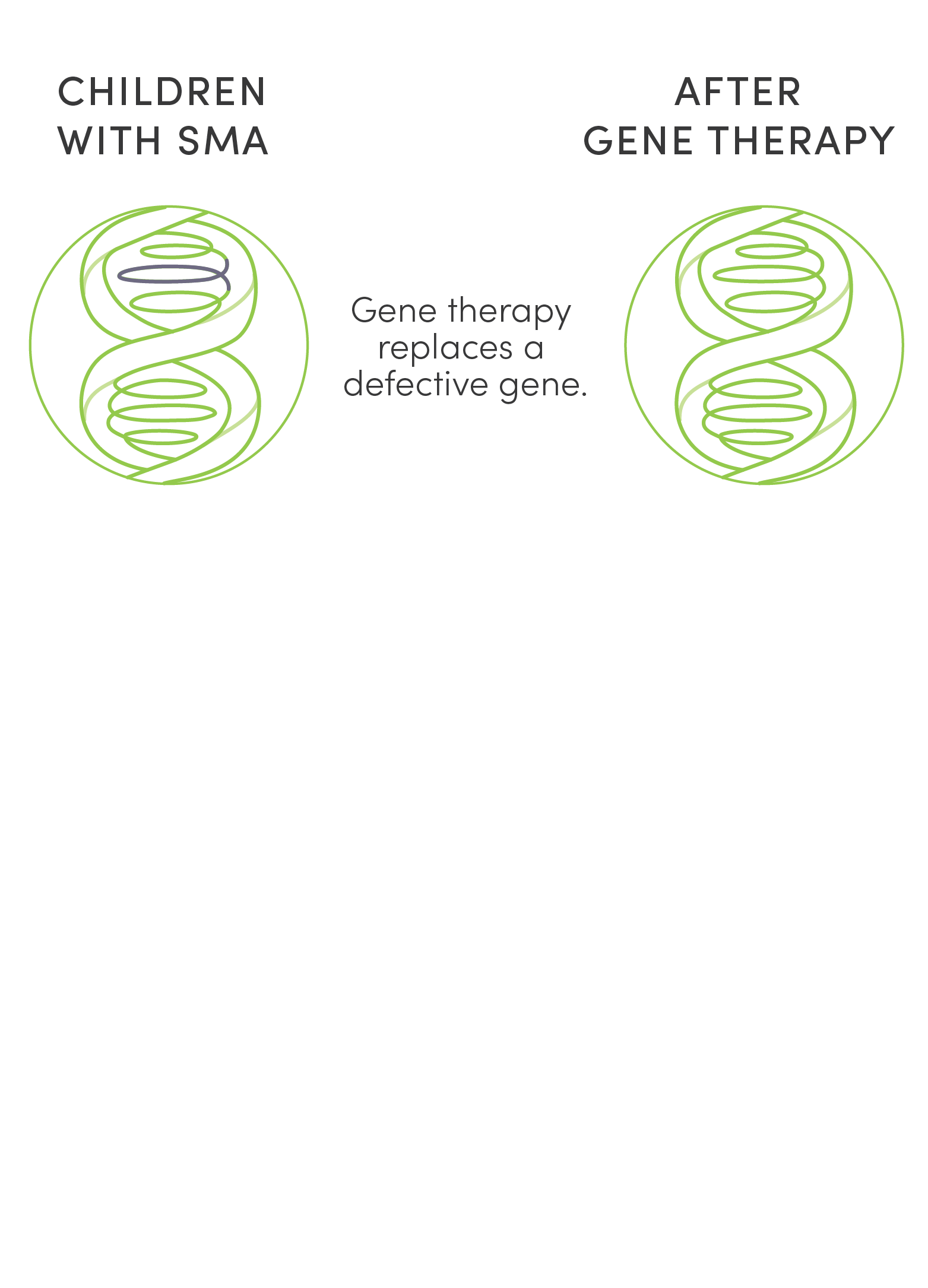

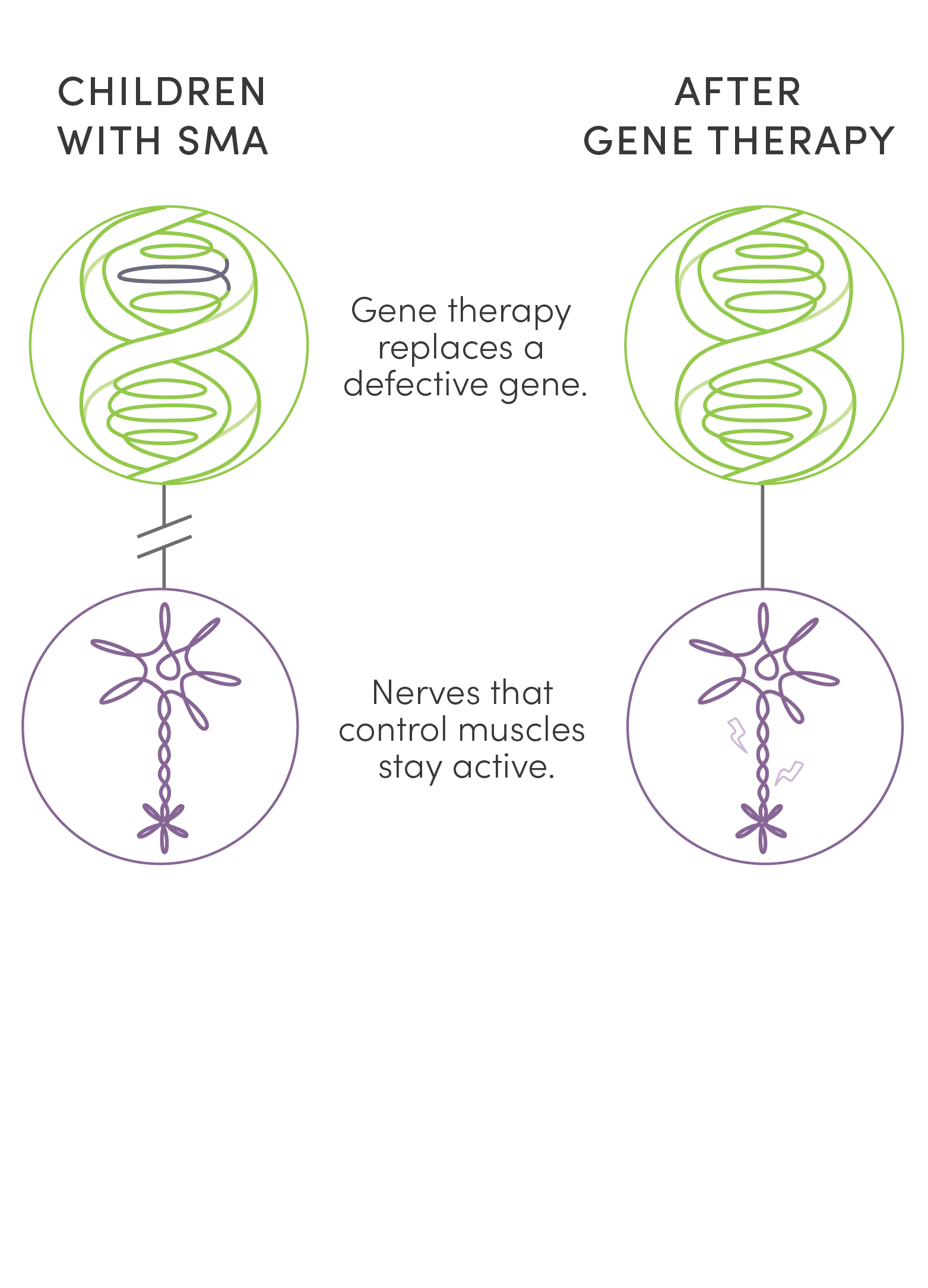

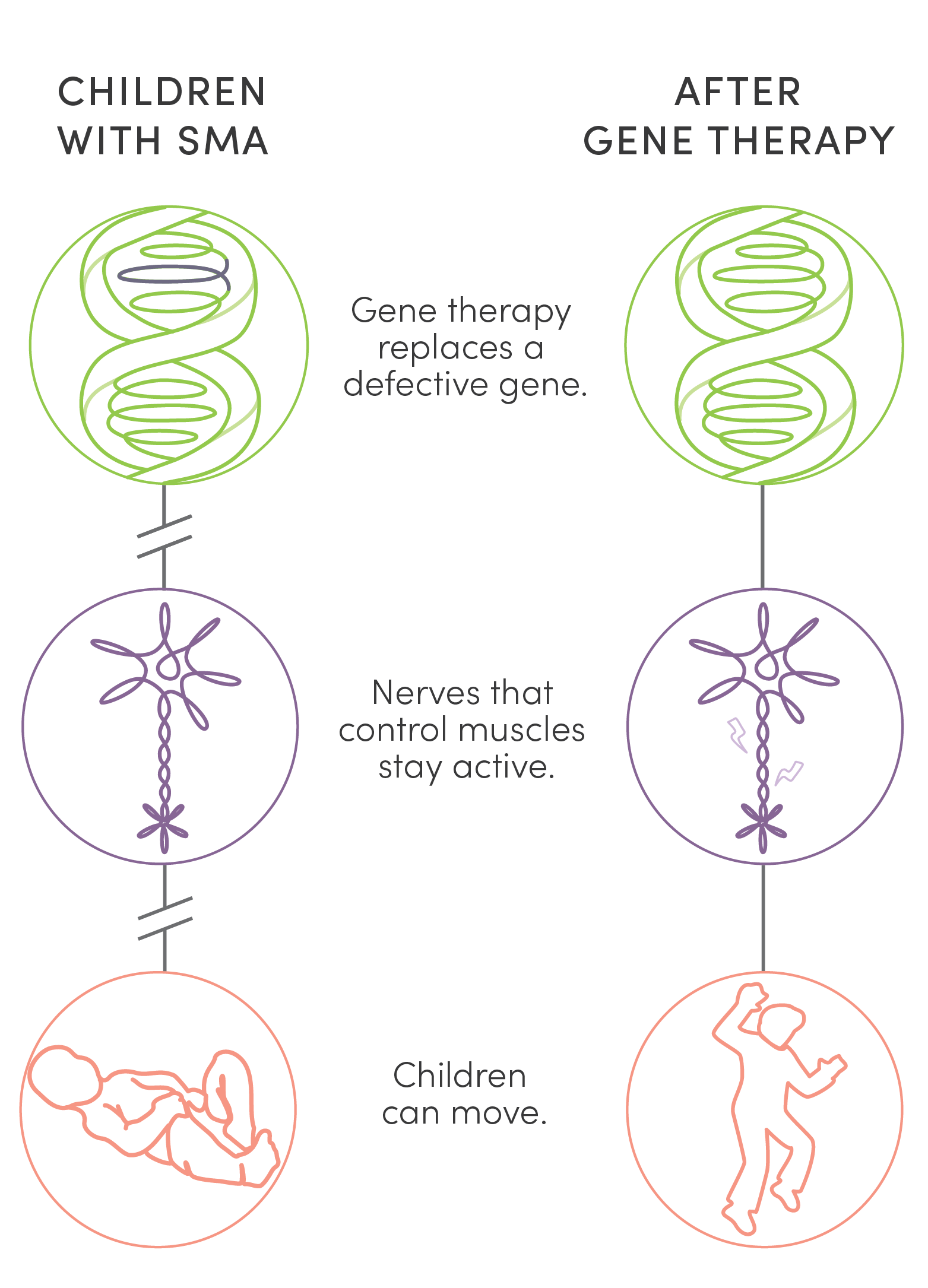

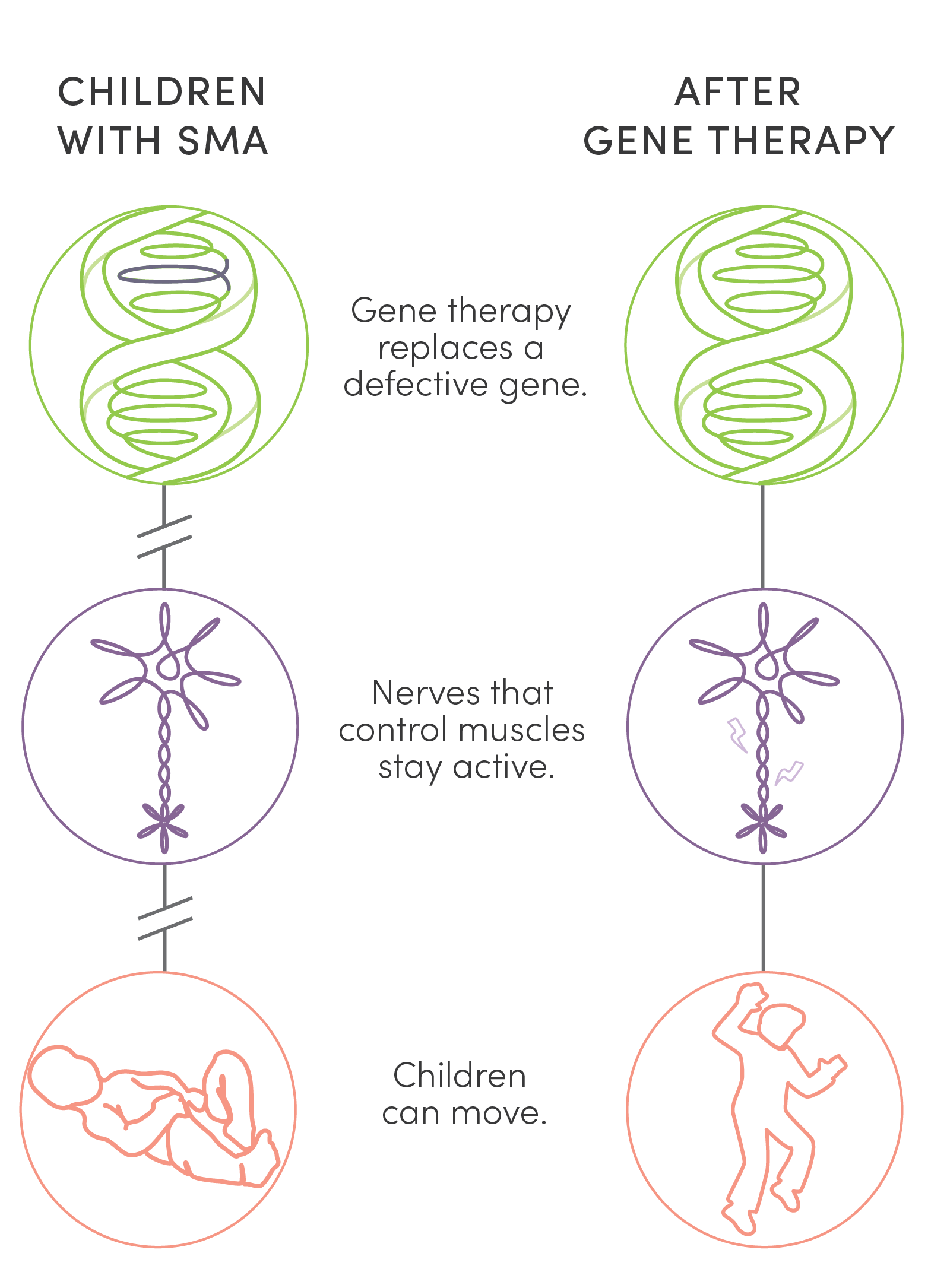

Unlike surgery or traditional medications, gene therapy is new kind of treatment that modifies a person’s genes to treat disease. Two gene therapies offered an answer to the tragedy of children’s lives cut short by SMA. UPIN was one of a handful of centers in the country to research, test, and ultimately administer them. While not cures, these therapies stave off life-shattering and, finally, fatal symptoms of the disease. This dramatic success has made SMA the poster child for the potential of gene therapy.

Brave new world

Fifteen years after Jonas Coleman’s death, a five-year-old boy ran up to an enormous window and gazed into a world of sharks and tortoises lazily swimming by. He was born with SMA, received a new type of treatment days after his birth, and has never displayed a single symptom. Children like him, who have received gene therapy for SMA, are beneficiaries of a revolution driven by a union of science, research, and medicine.

The boy was at a local aquarium where an annual family celebration was being thrown by the Utah Program for Inherited Neuromuscular Disorders (UPIN). UPIN works with families to research and treat inherited nerve or muscle disorders.

The program’s director, Russ Butterfield, MD, PhD, a specialist at U of U Health and Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital, put up a series of slides that cited recent U.S. Food & Drug Administration approval of treatments for genetic diseases.

“When I used to do these slides, the treatments were so far away,” Butterfield told the room. “Now we can’t keep up with them.”

Among the newly approved gene therapies was Elevidys for four- and five-year-old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD); a new genetic therapy for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS); a new treatment for the spinal cord nerve degenerative disease Friedreich’s ataxia; and a new steroid treatment for DMD approved that very week. As many as 60 new gene and cell therapies were expected to debut by 2030.

Butterfield compared the escalation in new treatments to the rollout of antibiotics 100 years ago. One day there was nothing, the next a life-saving drug that vanquished bacterial infection. Gene therapy is the same kind of game-changer.

Unlike surgery or traditional medications, gene therapy is a new kind of treatment that modifies a person’s genes to treat disease. Two gene therapies offered an answer to the tragedy of children’s lives cut short by SMA. UPIN was one of a handful of centers in the country to research, test, and ultimately administer them. While not cures, these therapies stave off life-shattering and, finally, fatal symptoms of the disease. This dramatic success has made SMA the poster child for the potential of gene therapy.

“Stay tuned,” Butterfield said to the patients and their families. “Gene therapy’s really the new world.”

“In the game”

Butterfield has always been drawn to the promise of gene therapy. As a Utah college student, he wrote a paper about how the treatment might one day provide a cure for cancer.

If there was a place in America to pursue that promise, Butterfield’s home state of Utah—with its lengthy history in genetics—was definitely a candidate. At that time, Utah scientists had discovered more human disease genes—breast cancer and colon cancer among them—than any other state in the nation.

Butterfield is the first to acknowledge he stands on the shoulders of those who came before him, including Jonas Coleman’s doctor, Kathy Swoboda, MD, who had been a neurogenetics specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Kathy Swoboda, MD, dedicated much of her career to treating, researching, and launching clinical trials for SMA. Her legacy includes co-founding in 2004 the Project Cure SMA Network, a group of investigators that designed and implemented novel treatment approaches for the disease.

Kathy Swoboda, MD, dedicated much of her career to treating, researching, and launching clinical trials for SMA. Her legacy includes co-founding in 2004 the Project Cure SMA Network, a group of investigators that designed and implemented novel treatment approaches for the disease.

Swoboda came to U of U Health and Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital in 1998 and cared for every baby with a neuromuscular disorder that came through their pediatric clinic. Starting in 2002, SMA was the major focus of her research and clinical work.

At Primary Children’s, Swoboda cared for families who often continued to have more children after having a child with SMA. This meant she could use a recently developed genetic test to determine whether younger siblings also inherited the disease.

The more babies Swoboda diagnosed, the clearer it became that there was a crucial window of opportunity for intervention. That critical time was during the first weeks of life, before symptoms began to emerge.

With that in mind, Swoboda scoured the country for clinical trials targeting SMA. Among the few she found was one that tested valproic acid—used for epilepsy and mental health conditions. Jonas took part in the valproic acid trial, but it had little effect.

Butterfield became a child neurology resident at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s in 2004. Seven years later, he finished his fellowship and started working with Swoboda, signing up for every trial they encountered.

“You’ve got to be in the game and know what’s coming,” Butterfield said.

How do you say goodbye?

In August 2010—a year after Whit and Lindsey’s son Jonas had died of SMA—Swoboda asked Whit to join her team as a nurse researcher. In that role, he glimpsed what other families were going through, some worse off than his family, some with better luck.

Whit’s lived experiences meant that he was gathering data and filling prescriptions for children with SMA—but he was also offering a gentle ear to grief-stricken parents. One family that came to him for help was Elliot and Janell Lewis.

After Janell gave birth to their first child, Blakely, in 2011, they quickly realized she wasn’t meeting her milestones. When she started having breathing difficulties, a doctor diagnosed Blakely with SMA.

Overnight, the Lewis’ expectations, their plans—their very life, it felt like—vanished.

Their cozy nursery morphed into a medical unit, with a Cough Assist suction unit, a pulse oximeter, and a BiPAP. Doctors surgically inserted a gastric feeding tube into Blakely’s stomach.

Blakely had both a zest for life and a pronounced enjoyment of the slapstick pain of others. She’d laugh if you stubbed your toe and cursed, or think it the funniest thing when a character was smushed in a Tinkerbell movie.

By the time she was 18 months old, she could only move her pincer fingers and her eyes. Even so, she’d let you know when she was happy—and when she wasn’t. In a room full of gifts for her first birthday, she laid on an ottoman, squealing with joy. Put the wrong DVD on and she’d look away until you got the message.

A video by Elliot Lewis shows his daughter Blakely at 21 months old, shortly before she died from SMA.

A video by Elliot Lewis shows his daughter Blakely at 21 months old, shortly before she died from SMA.

In Spring 2013, Blakely’s breathing collapsed due to a respiratory infection. By Blakely’s sixth day in hospital, “her little body had had enough,” said her father, Elliot.

Both parents opposed intubation, but as Blakely deteriorated, the decision whether to intubate or not grew only more pressing. Finally, on March 26, they withdrew the BiPAP, and while Janell held Blakely in her arms, she died.

Slipping away

Jonas’ father, Whit, felt it an honor to support Janell and Elliot during Blakely’s decline—and to aid other families who were going through the same experience. But even he reached his limit. At home, he was struggling with his own losses from SMA.

If Whit’s first child Jonas had been a dove, then his second child, Maggie, was a hummingbird. Like Jonas, she also had SMA. Despite her limitations, she wanted to see and do everything. She was feisty with a combative passion that seemed so much bigger than her disease.

She couldn’t sit up on her own, but she controlled her head movements and didn’t need as much help with breathing as some other children with SMA. She made sounds as if she were trying to talk to her parents, even if she couldn’t quite form the words.

Despite limitations in her ability to move, Maggie wanted to see and do everything. She died with SMA at the age of three.

Despite limitations in her ability to move, Maggie wanted to see and do everything. She died with SMA at the age of three.

On October 17, 2013, shortly after Maggie’s third birthday, she caught what her parents thought was a cold. They took her to the hospital but, to their disbelief, Maggie started to slip away. To her mother Lindsey, it seemed Maggie was saying, “I’m tired of this, I don’t like to be sick.” Ever a force of nature, Maggie left on her own terms.

Whit quit working for Swoboda shortly after. It all felt too close to home.

The promise of revolution

In Summer 2015, Swoboda left Utah for a senior position at Massachusetts General Hospital. Under the umbrella of the then newly formed UPIN, Russ Butterfield, MD, and his research partner Nick Johnson, MD, took over several phase 3 trials for a genetic therapy known as Spinraza.

One trial focused on SMA patients who had already developed symptoms, the other on pre-symptomatic SMA patients.

Spinraza went directly to the genetic root of the disease, activating a backup gene, SMN2, that can compensate for the absent SMN1 gene. It was a transient treatment, administered by spinal tap three times a year. For Butterfield, this was a kind of gene-based therapy he’d dreamed of in college.

The initial results from Spinraza looked promising. When given to children who had already developed SMA symptoms, the treatment slowed the disease’s progress and improved their movement and strength.

Symptomatic patients who had been motionless and silent were able to sit up, drive a wheelchair, and even vocalize. Butterfield marveled when one of the trial participants sang a short song.

If those results felt revolutionary, the next clinical trial delivered that revolution. Infants who received treatment much earlier—before disease symptoms started—were able to meet normal developmental milestones.

Ultimately, 23 of the 25 infants given the treatment within days to weeks after birth were eventually able to walk independently, something that children with untreated SMA could never do.

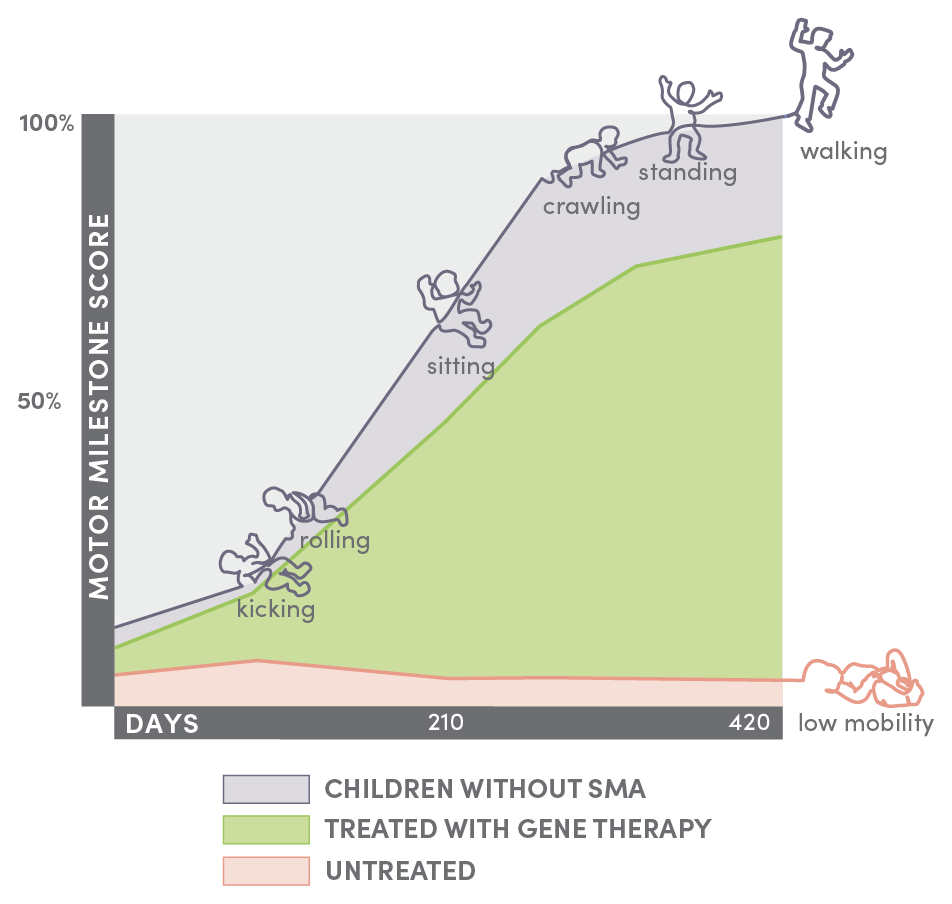

Infants with SMA* who were treated with Spinraza (green) reached movement milestones—such as rolling, crawling, and walking—but not as quickly as children who did not have SMA (purple). Infants with SMA who did not receive treatment had little mobility (orange). *Treated children had two copies of the SMN2 gene. Neuromuscular Disorders 29 (2019) 842–856.

Infants with SMA* who were treated with Spinraza (green) reached movement milestones—such as rolling, crawling, and walking—but not as quickly as children who did not have SMA (purple). Infants with SMA who did not receive treatment had little mobility (orange). *Treated children had two copies of the SMN2 gene. Neuromuscular Disorders 29 (2019) 842–856.

As 2016 headed toward a close, Janell and Elliot Lewis had conceived a second child, three years after the death of their first daughter Blakely. Through an amniocentesis test, they learned that their fetus had SMA. They signed up for clinical trials testing the genetic therapy, Spinraza, but didn’t have high hopes.

“I’ll be thrilled if she holds her head up,” Janell told Butterfield. That was something Blakely had never done.

Perhaps she might crawl, or even breathe on her own. And a longer life span? They would take whatever they could get.

“Muscle juice”

December 23, 2016, fell on a Friday. Staff were gearing up for the holidays. And then a bombshell hit: the FDA had approved the SMA genetic therapy Spinraza for commercial use.

UPIN staff were stunned. Its approval was faster than anyone expected. They had nothing in place in the way of purchasing, insurance billing, or medical infrastructure to administer the treatment to their 60 eligible patients.

Along with addressing all these issues, Butterfield also had to field calls from desperate parents who had gone from the euphoria of learning of the FDA’s decision to the agony of having to wait day after day, week after week, while UPIN scrambled to get everything in place to start administering doses of the new drug.

On March 6, 2017, Butterfield held the first baby in Utah to receive the drug commercially in one hand and the $125,000 Spinraza drug in a syringe in the other.

A baby with a death sentence and a drug that would give her life. It was a profound moment for everyone, including Butterfield.

As more infants came into the hospital for their first of four loading doses, in early April 2017 a new name was added to the list: Evie Snow Lewis, her middle name honoring her father Elliot’s passion for skiing.

Evie had a distinct advantage over other infants with SMA. Her disease had been diagnosed before she was born, giving her the chance to start treatment prior to the onset of symptoms. Her doctors and parents hoped to get Evie on Spinraza as soon as possible, but the medical and insurance infrastructure was still being worked out.

The resultant delays meant she didn’t get her first dose until day 12. By then, Evie had developed swallowing difficulties, which ultimately led to her needing a gastric tube surgically inserted through which a bolus of food was injected into her stomach every four hours.

She also developed a slight tremor in her hands and twitching in her tongue. Might they have been avoided if the drug had been available just days earlier, the Lewises wondered?

At 21 months old, Evie, who received gene therapy for SMA, can crawl, climb, walk, and hug. Video by Elliot Lewis.

At 21 months old, Evie, who received gene therapy for SMA, can crawl, climb, walk, and hug. Video by Elliot Lewis.

While Evie didn’t crawl until she was 16 months old, from there she started to clamber onto the sofa, push toys that supported walking, and, by 21 months, to walk.

In those first months, then years, to her astonished parents every single movement by their daughter seemed too good to be true. She was meeting normal developmental milestones, even if a little later than other children.

Evie looked forward to her triannual doses of what she called “muscle juice” as she grew up. “It’s just like when you go to get gas at the gas station,” she’d tell her parents. “You go when you need energy.”

When Butterfield asked the Lewises what they needed to know about Evie’s future, they asked about life expectancy. “Pretty normal,” he said. “I expect her to live a full life.”

A single shot

After the challenges of the commercial rollout of Spinraza in Utah, the debut of Zolgensma, a second SMA gene therapy, was more sedate. Yet the drug itself was in some ways an even more remarkable evolution in treatment. One of the first families to benefit from it was the Wights, who lived in Moroni, Utah.

Amber and Alex Wight married in late 2017, in their town’s old opera house. Alex worked for a farm and a coal mine while managing his own small herd of cows.

Amber got pregnant and gave birth to a son in late spring 2019.

Cinch was five weeks early. Alex was excited at the prospect of a little bronc rider working the farm with him.

The day after Cinch was born, the FDA approved Zolgensma for commercial use for infants up to two years old. If Spinraza played a genetic trick by activating the backup SMN2 gene, Zolgensma replaced the missing SMN1 gene with a healthy copy.

Rather than a lifetime of lumbar punctures, Zolgensma would be a single, one-hour IV infusion that cost a whopping $2.1 million.

The drug came with other challenges beyond its price. It used a viral vector—a protein shell—to deliver the gene. Doctors had to make sure the patient had no antibodies to the virus and then closely monitor the days of vomiting that followed infusion and other side effects that could be caused by a massive immune response to the viral vector.

By the time Cinch was born, another key weapon in the medical armory of defeating SMA had been put in place.

A lab technician at ARUP Laboratories runs the tests that comprise the screening of a newborn baby in Utah for 40 severe disorders, among them SMA.

A lab technician at ARUP Laboratories runs the tests that comprise the screening of a newborn baby in Utah for 40 severe disorders, among them SMA.

Utah became the first state to add SMA to their mandatory newborn screening on January 28, 2018, due in part to the hard work of Swoboda, Butterfield, and scientists at the Utah Department of Health. They knew they could do so much more for children with SMA if treatment were initiated soon after birth. Newborn screening made that possible.

In July 2018, SMA was added to the national list of diseases recommended by the federal government to all states for newborn screening. These milestones were huge steps forward in tackling the disease before symptoms emerged.

The new designation led to Amber getting a call from their primary care doctor a few days after her baby was born. The doctor had just received results from the Utah newborn screen. “Cinch came back positive for SMA,” he told Amber. He described how it attacked the muscles and that Cinch could die very young.

Butterfield called within the hour. “I heard you got some difficult news,” he said. He assured the family that treatments were available. They met with Butterfield at Primary Children’s the next day, and he told them about both drugs. A single-shot treatment? That was good enough for the Wights.

A month after the diagnosis, the Wights took Cinch to Primary Children’s to get the infusion. An IV team put the IV in place, a nurse checked the infusion was running, and Amber and Alex watched as their baby slept while the drug dripped into a tiny peripheral vein.

UPIN’s Russ Butterfield, Amber and Alex Wight stand next to Cinch as he receives his one and only hour-long infusion of Zolgensma.

UPIN’s Russ Butterfield, Amber and Alex Wight stand next to Cinch as he receives his one and only hour-long infusion of Zolgensma.

Cinch grew up largely out of the shadow of the hospital, other than regular visits for check-ups. Amber charted his every physical milestone: his rolling, his crawling, the first time he did things that she thought the disease might have denied him. He’d run and play with other children and she’d marvel how he never seemed to be still—other than when he was sleeping.

Alex wrote a short book about the cowboy life and dedicated it to his family: “I hope one day [Cinch] can be a cowboy like me.”

Alex wrote a short book about the cowboy life and dedicated it to his family: “I hope one day [Cinch] can be a cowboy like me.”

Reach for the moon

The story of SMA’s transformation from child killer to preventable disease underscores the enormous potential of gene therapy.

For all the gene and molecular therapies for diseases on the horizon, Swoboda argued that none so far had proved as radically effective as those for SMA. So much more was known about detection and SMA’s early development thanks to work by her and Butterfield, among others. “It’s the most transformational neurogenetics treatment intervention in this century so far,” Swoboda said.

The far-reaching nature of that potential to save lives is only now just beginning to emerge. In early December 2023, the FDA approved two gene therapies for sickle cell anemia, one of the most common inherited diseases in the world.

The speed at which gene therapy is evolving inevitably leads to questions that can’t yet be answered. For SMA, there are questions relating to how long the drugs’ impacts will last. Years, decades, a lifetime? No one knows.

Will combinations of these drugs be more effective? What if side effects emerge? UPIN is one of a handful of U.S. clinical and research centers navigating this new frontier. “The research we do is a result of our commitment to giving the best care to our patients,” Butterfield said.

One research program aims to improve current methods for assessing motor development and impairment. The research, conducted by UPIN’s Melissa McIntryre (pictured below), focuses on wearable sensors put on newborn infants.

One research program aims to improve current methods for assessing motor development and impairment. The research, conducted by UPIN’s Melissa McIntryre (pictured below), focuses on wearable sensors put on newborn infants.

McIntyre’s sensors allow her and her colleagues to assess infant motion earlier in life and for longer periods than previously achieved. This model may be more sensitive to changes in a baby’s motions, improving predictions of how SMA babies will develop.

McIntyre’s sensors allow her and her colleagues to assess infant motion earlier in life and for longer periods than previously achieved. This model may be more sensitive to changes in a baby’s motions, improving predictions of how SMA babies will develop.

There are also questions about the future of gene therapy. They include the ever-mushrooming price of each new treatment; addressing regulatory and safety concerns; building the medical infrastructure to support distribution of these new therapies; and educating the wider medical community about the far-reaching impact gene therapy will have on their patients’ health.

There are inevitably disappointments: Sarepta announced that Elevidys, their just FDA-approved Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy, did not achieve its primary goal in clinical trials.

But as SMA proved, these are barriers that can and must be overcome if the potential promise of gene therapy is to be realized.

Whit and Lindsey Coleman understand that SMA’s gene therapies deliver more than astonishing treatments. They offer hope.

In the aftermath of Jonas’ and Maggie’s death, the Colemans had two more children, both SMA negative. In 2020, they had a third child, which a blood test during pregnancy revealed had SMA. With the gene therapies now available, the Colemans knew that the diagnosis was no longer terminal—now, it was treatable.

Butterfield ordered Zolgensma for Lindsey’s due date, but the newborn screening test revealed their baby was actually SMA negative.

When people asked Whit how many children he had, he would pause sometimes, wondering if he should open the door to talking about Jonas and Maggie. For him, Lindsey, and their three children, Jonas and Maggie are also very much part of their family. He’d smile and say, “Actually, I have five,” and step through that door.

The pizza slice

In Janell and Elliot Lewis’ garage, a 6-foot-by-6-foot sign leans against a wall. “Never Give Up,” it proclaims. It’s the motto of a nonprofit dedicated to funding SMA research in the name of Gwendolyn Strong, a child lost to the disease.

The motto of an SMA nonprofit leans against a wall in the Lewis’ garage.

The motto of an SMA nonprofit leans against a wall in the Lewis’ garage.

That motto seems all but incarnate in the energy and passion the Lewis’ six-year-old daughter Evie brings to her life and that of her parents. She realizes dreams her parents had for Blakely that her diagnosis and early death erased.

One such dream was Elliot skiing with his child. While he knew that, with SMA, Evie’s range of motion would be limited by the disease, “What we didn’t know was if she’d ever be able to sit, crawl, walk, or even grow up, much less ski,” he shared on a vlog entitled “Realization of a dream.”

One bluebird winter’s day at Snowbasin in 2022, they took Evie up to the slopes to teach her to ski. Even though she was scared, whimpering as Lewis put her boots on to the skis and clicked them down, even though she cried when she fell and wanted to go home, she and Elliot persevered.

“Go baby,” Janell called out.

Elliot taught Evie how to slow her descent by narrowing together the front of her skis into the shape of a pizza slice. At first, Elliot held her between his knees, then had her ski alongside him.

“I’m doing it,” Evie said excitedly.

Elliot skied ahead of her and turned around, facing her as she skied for the first time on her own. She came down the slope, her skis narrowing into the pizza triangle, arms open wide, until she landed in his arms.

“Gotcha,” she cried triumphantly.

Visit “SMA DAD” on YouTube to follow Evie’s journey.

Stephen Dark – Writer

Jessica Cagle – Designer

Stace Hasegawa – Illustrator

Julie Kiefer, PhD – Editor, producer, science advisor

Jesse Colby – Art director

Nick McGregor – Copy editor

Suzanne Winchester – Consultant

PHOTO CREDITS

Charlie Ehlert – Portrait of Russell Butterfield, MD, PhD; photos of Melissa McIntyre and her research, along with the Lewis family at home.

Niki Chan Wylie – Photos of the Coleman and Wight families at home.

Heather Parkinson – ARUP Laboratories photo.

Kristan Jacobsen – Portrait of Kathy Swoboda, MD.

Personal photographs provided by Whit Coleman.

Personal videos provided by Elliot Lewis.

Dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their fight against SMA, the families who loved them, and the many who have worked passionately to ensure that no parent should have to endure their infant having a terminal SMA diagnosis.