ANGELS IN THE SKY

In five offices, in five buildings scattered across Utah and Wyoming, three urgent beeps ring out, announcing yet another emergency in need of air ambulance support.

In a double-wide on the outskirts of Park City by a water reclamation plant; in a trailer outside Tooele next to a field of grazing cows; in an apartment complex in Nephi; in a medical building next to a Davis County hospital; in a small plane airport office in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

In all these offices, men and women dressed in the black, fire-retardant one—piece suits of AirMed, University of Utah’s air ambulance service, freeze as the tones reverberate through their offices.

They wait to hear if they are the ones to be sent into the sky on the next AirMed mission. It could be an inter-facility transfer of a patient from an ER to University Hospital, or a dramatic flight out to a desolate spot on a highway to ferry a roll-over survivor to the hospital. Either way, when those beeps sound, the atmosphere in every AirMed base in Utah and Wyoming is electric.

“I still get butterflies when the tone goes off, even after 15 years,” says Nathan Morreale, chief flight paramedic. When it’s his station, “you feel the tension ramp up. You’ve got 10 minutes to take off.”

Or, as flight nurse George Jan puts it, “It’s game face.” He’ll grab the blood from the fridge and time-stamp it, while paramedic Steve Conger helps the pilot finalize information for the flight. They are expected to be off the ground within 10 minutes of receiving the assignment from Flight Center at University Hospital. “You can’t rush, otherwise there’s a chance of missing something,” Jan says. “But you can’t dilly-dally either. There’s a sense of deliberate urgency; this is never the small stuff, it’s always urgent, critical, life-saving.”

Each of the bases can reach University Hospital's helipad within approximately 20 minutes. But AirMed is not simply about flying a patient to the trauma 1 center to get them state-of-the-art care. It’s about providing that same quality of care in the field and in flight while in precarious, cramped quarters where anything can and does go wrong. And to do that, you need crews who are typically alpha-type personalities, who thrive on autonomy and adrenaline. It can be tough to survive otherwise.

In AirMed’s ranks, you’ll find ex-NFL footballers, a former TV show assistant director, ice-mountain climbers and adventurers, sky divers and international surfers, and they all have one thing in common: they are operating at the top of their medical license. Flight nurses require a minimum of five years’ experience in the ER and ICU at a trauma 1 facility, while flight paramedics need five years with a high-volume 911 service. They have a wealth of state-of-the-art equipment and training to draw on to treat emergency burn patients, cardiac arrests, trauma, neonatal, pediatric, and high-risk OB/GYN cases. Ultimately, it’s their finely honed instincts and independent spirits that are the true cutting edge of their service. Making life-saving decisions under intense pressure in the most confined of spaces as turbulence shakes the helicopter’s frame requires nothing less.

Hospital employees regularly see an AirMed crew of flight nurse and medic, perhaps a respiratory specialist or flight physician, sauntering back post-mission through corridors, their equipment on their gurney, after yet another high-octane, patient-in-dire-distress delivery. But few understand what sets AirMed staff apart, says medical director Eric Swanson. “I can’t underestimate how cool it is to get into a helicopter, fly wherever it is, and take care of the sickest of the sick.”

With such privilege inevitably comes so much responsibility, so much weight on their shoulders.

“We have one patient, a set amount of time to care for them, and we have to be really fast and accurate. We don’t get any misses.”

When it comes to patient transportation from one facility to another—typically to University Hospital—the flight nurse takes the lead. But when the call is to a scene—a car crash on a highway, an accident in the mountains, a hurt child in a rural county—that’s where the paramedic shines, says flight nurse manager Deborah Witte.

Each has their pre-designated roles along with the need to always be communicating with the rest of that day’s allotted team, whether it’s an odd word because they know each other so well or more substantial back-and-forth when they are new to the flight crew. Teamwork is crucial. “We fly into the scene, we’re talking to each other about the information we have, about who’s giving meds and who’s intubating, who’s doing what on the aircraft,” Witte says.

The core team of paramedic and nurse need to be seamless. “We function best as equal team members,” Witte says. “We’re a continuum of patient care focused on the best patient outcome.”

And it’s not just the 112 nurses and paramedics. There’s a 36-strong pilot and mechanics team who work for Metro Aviation under contract to U of U Health. The pilots fly seven helicopters and two airplanes. AirMed’s vehicular assets reflect a reality few air ambulance services face nationwide, which is the enormity of their service area. It covers not only Utah and Wyoming, home to the seven bases, but also Nevada, Colorado and Idaho. It can mean fighting to keep a patient alive for sometimes as long as two hours.

Their distinctive University of Utah colors of red, black, and white flash in the sun as they fly over Salt Lake Valley or out to rural communities, rushing highly specialized health care not available in regional hospitals. To tell the story of AirMed is to recognize the tragedies of the past and the safety culture that grew out of them, and the remarkable individuals who wear with pride and humility the AirMed logo on the back of their fire-retardant suits. For veteran AirMed nurse Janie Ford, her vocation has been an honor to pursue.

“I have had the privilege to be inserted into the worst day of people’s lives and take care of them like I would a family member. It’s a pretty sacred obligation in my opinion.”

HONORING THE FALLEN

When AirMed began in 1978, it was the eighth program in the country. The seventh, launched the year before, was Intermountain Life Flight (at that time operated by LDS Hospital). The two have maintained both a rivalry and a friendship, taking up the slack when for whatever reason the other can’t.

Fireman Brent Speirs hired on to AirMed in 1982. Back then, U of U Health’s air ambulance program was behind the eight ball in comparison to Life Flight. While Intermountain Healthcare's program provided coverage 24/7, AirMed had availability only from 8 am to 5 pm. Speirs’ arrival was part of building a second eight-hour shift. But several tragedies shortly after he joined shocked his resolve and that of his colleagues to the core.

On April 11, 1983, in the face of snow, fog, and poor visibility, AirMed pilot Louis A. Mertz had turned down a flight request to ferry a pediatric team to a very sick infant. After several more requests highlighting the infant’s mortality, Mertz said, “I feel really uncomfortable about this flight,” but nevertheless lifted off the pad. Shortly after taking off from the U of U helipad in a Bell 206L Long Ranger, he flew over the stadium and circled, deciding the weather was simply too poor to head south. Although it was just a short journey back to the helipad, he become disorientated in the all-encompassing squall that had consumed the U. Mertz collided with the foothills, just above the university’s U sign.

Mertz was the first loss an air ambulance service had sustained in Utah. After that tragedy, rules were put in place to separate pilot and crew from health care providers, and all requests after that were routed through flight control. From then on, pilot and crew determined a flight solely on safety grounds.

Worse was to come in 1998.

Shortly after an exhausted Speirs had crawled into bed at 11 pm on January 11, the wind and snow pellets hammered his windows with such eerie violence it kept him awake. As he lay there listening to the storm, the phone rang. “We’ve lost contact with the helicopter,” a dispatcher told Speirs.

AirMed 6, a Bell 220 chopper, had been dispatched to Little Cottonwood Canyon to pick up a skier injured in an avalanche. No one had heard from the pilot and medical crew for 30 minutes, and concerned AirMed crews were starting to gather at University Hospital to await news.

Speirs went to Valley Emergency Communication Center so he could pass on information as it came in from emergency services to his worried colleagues at Flight Control. He learned that the flight nurse and paramedic had loaded the patient onboard the Bell 220, just below the Snowbird trailhead. The team was tired, cold, and hungry, and their shift was almost over. They wanted to go home. The veteran pilot took off down the canyon to try to break out under the clouds, only to be driven back by a storm front that forced him to bank and come back over the landing zone so he could set down. But it was snowing too hard to land, so he headed straight up, only for the front to hit them again, pushing the helicopter towards the canyon wall. The nose dipped, the blade clipped the tip of the pine tree, the pilot lost control, and the helicopter slammed into Dromedary Peak.

On the north slope, the sheriff and deputies spotted burning wreckage. It took two and a half hours to get to the crash site. “We’re here and there are no survivors,” the sheriff reported. The pilot, flight nurse, and flight paramedic, along with the male patient, all lost their lives.

The crash impacted everybody on the team. “You take a risk every time you go up,” Speirs says. A disaster and such a loss of intimates “rattles your chain.” Some of the paramedics and nurses quit. The funerals were sobering reminders of who had been lost. AirMed and Life Flight did flyovers to honor the partners and families of those who had died. Fire departments hung flags from their extended ladders over I-15 as the coffins were transported to their resting place.

In the years since, crews have relied on each other for safety. They are all charged with looking for aircraft. If the pilot, paramedic, flight nurse or dispatch has any doubts whatsoever about the mission, one vote against proceeding cancels the trip, no questions asked. “Four to go—one for no,” runs the mantra.

After the crash, AirMed's helicopters and planes received new radios and satellite tracking of location, altitude, speed and heading every 30 seconds. The crews also benefited from becoming voice-data capable, which means even outside of radio range, they can still communicate.

As AirMed's newly appointed medical director the year after the crash, Eric Swanson pursued a shift in philosophy. Rather than being reactive and competing locally with Life Flight, he wanted to channel his team’s energy and commitment into trying to be the best in the country. Part of that was to be cutting edge, Swanson says—for example, being first in the region to fly with night vision goggles and also first to research and incorporate many new medical therapies and techniques.

FLIGHT CENTER

Get home safely

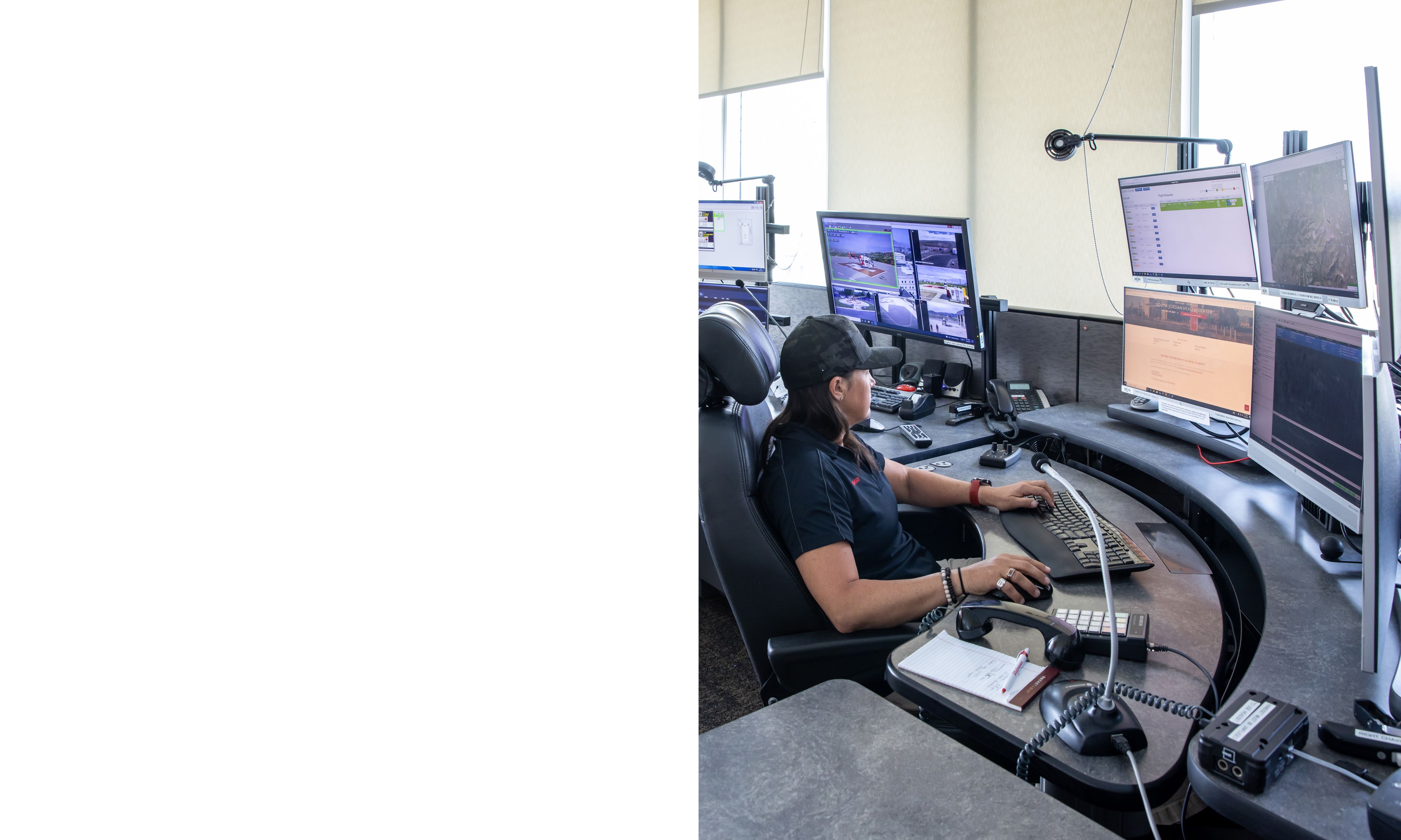

In AirMed’s Flight Control Center, supervisor Roxanne Fawson and her team of 12 dispatchers take turns in pairs receiving calls for help from 911 centers and other medical facilities—and dispatch crews from the different bases.

“We’re their safety net, their big brother,” Fawson says about her and her colleagues’ responsibilities to both crews and their patients.

“I feel like our job is to ensure patient and crew have what they need and go home safely at the end of the day.”

She became a 911 dispatcher at age 19, doing the job for 15 years. “It’s 12 hours and nobody’s calling to tell you happy things,” she recalls. As opposed to trying to calm people in their direst moments of life, Flight Center requires a combination of dispatcher and air traffic controller skills. “Here we mostly communicate with hospitals and dispatch centers who call for transport.” The 13 flight coordinators are trained in aviation, weather, GPS, and how the aircraft perform. Her staff need to know that helicopters can’t fly in high temperatures, that single-engine aircraft, per Federal Aviation Administration rules, aren’t allowed to fly over large bodies of water, along with myriad other regulations and mechanical necessities.

Shift changes for AirMed bases are staggered across the two states, so Flight Center staff can brief on the phone with the outgoing and incoming teams of pilot, paramedic, and nurse to make sure “everyone is on the same page,” Fawson says. That includes the flight coordinator’s shift partner. When they are on the phone with dispatch, a hospital, or an ER, they repeat back what the caller is saying and speak loudly so their partner can hear them spell out what is needed and jump on it.

“'Hey Brigham City hospital, you need us to fly out there for such and such a patient?’” Fawson role plays in a loud voice. “'Sure. How much does the patient weigh?’ I want my partner to get that aircraft started.” Weight is crucial information—in higher temperatures, there’s a weight cap that cannot be superseded if the aircraft is to fly.

It helps to be a multi-tasker, Fawson says, listening to the radio and the phone at the same time as typing. “Sometimes it gets crazy in here.”

Much like the work for nurses and paramedics, the flights can be emotionally challenging for Flight Center staff too, Fawson says. “You might work a 12-hour shift and have one or two children die. You think it’s not affecting you, then you suddenly break.”

Which is why, she continues, self-care is so important. “As a supervisor, I encourage everyone to take care of themselves mentally and emotionally, to lean on their family and on each other, and to utilize the Employee Assistance Program provided by University of Utah for employees.”

THE PILOTS

The final call

Jason Brown fell in love with the idea of being an AirMed pilot while doing homework as a child on the grass by the U of U helipad. The then-Judge Memorial student would lie prone on the grass with his books, waiting for the first whir of a helicopter’s engine coming to life. Over the months he’d hang out there, he’d always hope one of the staff would invite him to see an aircraft, but no one did.

When he was a college freshman, he mustered up the courage to ask at the gate to talk to a pilot about a career in flying. He had dinner—which he paid for himself—in the mess with a former Vietnam military pilot, who was painfully clear about Brown’s suitability for the task.

“You’ll never make it as a helicopter pilot unless you’re a military guy,” he told the crestfallen freshman. But such dire admonitions did little to deter Brown from his chosen path.

Brown took the civilian route, going to flight school on his own dime. Eventually, in 2000, he was hired on at AirMed. His first day, when he walked into the office, he found the duty pilot was the same man who had told him six years before only military flyers could do the job.

“You don’t remember me, do you?” he told him with a satisfied smile, introducing himself as AirMed’s first civilian pilot.

The key for pilot hires is not that they need to know how to fly well—that’s a given—but rather that they make decisions with the same autonomy and precision as their medical crew. “We don’t hire because they know how to fly; we hire them to make really sound decisions,” Brown says. “Ultimately, they are the ones on the pointy end of that stick.” As with the paramedic and nurse, there’s no margin for error, Brown stresses. “This business is very unforgiving. You make a mistake, there’s very little margin to get it right.”

Pilots experience some of the same tragedies that their medical crew have to process. Brown recalls a hunter who fell asleep at the wheel and hit a tree in his truck. The engine landed on his chest and he was close to death. The flight nurse knew when they took the engine off him, he would very likely not survive.

“She did everything she possibly could to try to keep him stabilized,” Brown says. She talked to doctors at University Hospital, running through every alternative scenario, until all involved “concluded there was no positive outcome for this.”

Brown is silent for a moment. “I can still picture him… she gave him her phone to call his wife to say goodbye. That tore everybody up. It was horrible. He did his thing, we took the engine off, we tried, we transported him, but he was dead.”

FLIGHT PARAMEDIC

Four kilos of dread

Paramedic Nick Volz found his first flights daunting—not so much because of what he was being asked to do, but rather where he was asked to do them. “The environment (of a helicopter) is overwhelming: it’s small, it’s loud, it vibrates, there’s not very good heat and not very good air conditioning,” Volz says. Those are all what’s called stressors of flight. “Add them on to that you’re taking care of some of the sickest patients you have ever seen and it’s a lot.”

His first air medical flight was with another air ambulance service in the Midwest. His orientation had gone smoothly and his last accompanied flight had been a very sick patient on a balloon pump with seven drips. Now he was on his own, ready to strike out as a flight paramedic. He would be fine, he assured himself. He could deal with trauma, cardiac problems, burns, and other medical events after years on the street responding to fires and rushing road traffic accident survivors to the ER.

Except for one category of patient.

“As long as the first call isn’t a teeny tiny baby, I’ll be OK,” he told himself.

His first solo shift was at night. The hours went by without the crew receiving a single call.

Then the beeps sounded.

“We’ll accept,” the pilot told flight control. How much did the patient weigh, the pilot asked? “Four kilos,” he said, jotting it down.

Volz was taken aback. The patient was a critically ill four-week-old baby. As the helicopter took off, his silence spoke volumes to his partner who told him over the intercom, “We’re going to be fine. Just don’t run away. We’ll make it work.”

Despite his nerves, it all came together for Volz with the support of his crew. “That night taught me a lot. You can work through it. Right off the bat, it taught me you have a partner, you’re a team, you work together.”

That working together requires intensely focused communication between crew members. Back when AirMed crews totaled just eight employees, it was a tight-knit family where a nurse and a paramedic knew what the other was thinking without having to ask because they worked together so much. As AirMed has grown to a roster of 30 nurses and 40 paramedics (many of them part-time), 16 specialty team members such as an OB perinatologist, along with another six or 10 respiratory therapists, the guarantee of working with crew members you have a relationship with—with whom you can communicate using only sound bites—becomes rarer. Reading body language and knowing how your partner thinks without having to ask isn’t always possible, so sometimes verbal communication has to come to the fore.

That’s just one reason why communications skills are so important for nurses.

“These are high-adrenaline situations. You wouldn’t be there if everyone was having a good day.”

When a flight nurse arrives on-scene, a key part of what they do is outreach and PR, says veteran AirMed nurse Janie Ford. “You can lose business so quickly if you snap at someone. It’s so easy to say the wrong thing.”

Veteran AirMed paramedic (and now retiree) Brent Speirs emphasizes that the ground paramedics who greet the AirMed crew at the scene are part of the team. “Nobody can give a better history than the paramedics on the street, so our philosophy is to work with them as a team.” At the same time, there can be a lot of politics involved. “You have to play well with other people out there,” Ford says.

FLIGHT NURSES:

The 1,000 foot picture

Deborah Witte fell in love with the idea of becoming a flight nurse while working on an episodic TV series. The registered nurse graduate had worked in the University Hospital float pool for three years when her aunt, a writer and producer for CBS and Hallmark, was looking for a medic to work on the set of “Touched by an Angel.” She lasted six months as on-set medic, a role the passionate skydiver quickly learned would not test her mettle the way she had hoped. She wrangled her way into jobs as runner, gopher, and then production assistant. After nine years with the show, the 27-year-old had risen to assistant director. While filming an episode starring country singer Travis Tritt, a scene called for a boy to be flown to the hospital. It was shot at the Salt Lake Regional helipad, and as she watched the helicopter land and the crew jump out, she thought, “You can fly and be a nurse? This is what I want to do.”

AirMed program manager Frankie Toon argues that what makes a good flight nurse are qualities of resilience, compassion, and the ability to bring calm and knowledge to a chaotic situation. “You have to be able to deal with a variety of situations and think through not only the care of the patient but a host of other potential scenarios.”

Paramedics’ pre-hospital experience means they are used to adapting to fluid situations on the street. But for nurses without such experience, AirMed can be a challenge. If things go south, a nurse can’t ask another nurse to watch her patient while she takes a moment to adjust, Toon says. “If the weather goes bad and you can’t complete transportation; if there’s a mechanical issue with the helicopter; if the patient’s condition changes, you can’t let those things startle or affect you. You have to push on. ‘OK, we’re not going to make it to University Hospital. We’ll go by ground.’ Or: ‘Oh no, the patient isn’t breathing, we’ve got to intubate her on the fly.’”

Veteran flight nurse Lisa Brasher argues that you can never know everything. In the first years of flying with AirMed, there was an element, at least for her, of sometimes simply trusting your instinct, regardless of your specific knowledge level. “The thing that is scary is that you have so much responsibility, you have to know a lot about a wide range of things, that even with a background in the ICU and ER, you’re certainly never ready for everything.”

Which is why part of meshing with AirMed’s culture and personnel is having self-confidence. “If you walked into any situation and they saw doubt on our faces, they’d never trust us,” Volz says. “We’re asking facilities and families to just trust us.” AirMed crews, he argues, draw some of that confidence from looking at the big picture, both literally and metaphorically, of the thousand-foot view from above and bringing a sense of calm and distance to the situation.

Self-confidence is still a line to be trodden carefully. The more experience Brasher gained, the more she realized she didn’t know. And it scared her. “If you ever feel too confident in yourself, you’re going to get burned. We all like things to go really well, but in this job, they don’t always go that way. You have to be able to adjust. It’s been a learning curve that’s taken years.” With a laugh, she adds, “I think you kind of fake it till you make it.”

Part of that learning curve is lessons learned the hard way, such as the need to always check post-flight or pre-flight that every single item needed onboard is present, correct, and in working order.

Brent Speirs only became a self-described zealot checking the helicopter for every single item of equipment after being on a transport from Rock Springs. A monitor’s battery died and there was no replacement. “There’s not a worse feeling in the world than to go on a flight thinking you had every piece of equipment and you ended up not having it,” he says. “I got in the mindset as soon as the team briefing is over, I check all of it, alone, for 1.5 to 2 hours.”

OUR TOWN, OUR PEOPLE

Mental health resources for air ambulance staff are evolving, says Jason Brown, who knows how devastating a loss can be for his colleagues. “We probably need more help than we recognize we need. We are all very good at compartmentalizing. I’ve seen nurses and medics just crumpled over in the corner, and they did everything they thought they could do to save that person and they didn’t.”

That doesn’t surprise chief flight paramedic Nate Morreale. “Everybody in this business has calls they never forget, good and bad ones. The good ones carry you through, keep you coming back. The difficult ones can hang on for years. I have lost kids, have lost parents with kids in the same vehicle—those are the ones that are difficult to carry for sure.”

There will be those calls where despite all they do, while parents and loved ones watch in desperation, both provider and patient run out of options. Witte recalls one youth who had been severely injured after an ATV accident in sand dunes. She and her partner worked on him for 35 minutes without any improvement. After she’d talked to doctors at University Hospital and no one had any more recommendations for treatment, she called the parents over.

“I told them, ‘Come and say your goodbyes; touch him and kiss him and say what you need to say; have as much time as you need.’” She held onto the mother because she knew, as a mom herself, there were no words she could say. “It was heartbreaking.”

But then there are the calls where, as Swanson says, it all comes together. A skydiver came in from a short scene flight, “a broken person with multiple fractures to her skull, face, pelvis, thorax, and every extremity.” When Swanson first saw her, “she was drowning in her own blood, a shattered human.” Months later, a young woman came to the hospital and asked to see him, all smiles and healthy body. It was the skydiver come to thank him.

“This is why we do what we do,” he thought.

He told the woman, “If this never happens to me again, my whole career has been worth it just for this. What I saw at your accident of how you were this human barely alive, and now look at you.”

Such patient-status updates are a rare occurrence, but it speaks to a bigger picture. “I know there are hundreds of those people out there that have had a chance they otherwise wouldn’t have if we weren’t there,” Swanson says.

For so many AirMed crew members, this job is the only one they ever want. It’s the pinnacle of their achievement. “We are operating at the top of our license, and there’s a lot of pride putting that flight suit on every day,” Morreale says. It’s an odd balance of confidence and humility. “You have to be the best of the best, but you also need to be humble,” he says.

Perhaps the humility stems not only from the almost God-like precision they have to bring to decisions that sometimes still don’t deliver patients from the jaws of death, but also from how connected these crews are to the people they transport and fly over: their community.

The family that crews form—a family of comrades in flight—and the families they serve make up their community. As much as an air ambulance service cares for their community, it's also a part of it, Morreale says. “I really like to believe we are part of the community as a flight program. We all live where we work. These patients that we’re treating and flying in a way are almost our family. We really like to believe we treat them as we would our own family, as part of the community we work in.”

What Brasher loves about AirMed is how the work she does impacts the lives of others. “In a very critical time, you make an absolute difference,” she says.

At one scene, she’d helicoptered in with a paramedic to pick up a four-year-old girl hit by a motorcycle. The child was severely injured and Brasher asked the mother if she wanted to come with them back to the hospital. “I didn’t want mom’s last vision of her daughter being broken on the road.”

The paramedic put an airway into the child’s throat while Brasher gave her medication. Then, with the mother in a seat in the helicopter opposite Brasher, they transported the girl to hospital. Afterward, concerned about the child’s fate, she contacted the mother and found out her daughter had made it through surgery and was on the road to recovery.

The two have remained in touch with Christmas cards over the years. Brasher pauses for a second to savor the name the mother gave her: her angel in the sky.

A SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL INVOLVED

WRITER STEPHEN DARK

DESIGN STACE HASEGAWA

PHOTOS CHARLIE EHLERT

and many contributing photographers throughout the years

Additional thanks to Cory Cox and Frankie Toon